Integrating a Multi-Tiered System of Supports With Comprehensive School Counseling Programs

Article , Volume 6 - Issue 3

Jolie Ziomek-Daigle, Emily Goodman-Scott, Jason Cavin, Peg Donohue

A multi-tiered system of supports, including Response to Intervention and Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports, is a widely utilized framework implemented in K–12 schools to address the academic and behavioral needs of all students. School counselors are leaders who facilitate comprehensive school counseling programs and demonstrate their relevance to school initiatives and centrality to the school’s mission. The purpose of this article is to discuss both a multi-tiered system of supports and comprehensive school counseling programs, demonstrating the overlap between the two frameworks. Specific similarities include: leadership team and collaboration, coordinated services, school counselor roles, data collection, evidence-based practices, equity, cultural responsiveness, advocacy, prevention, positive school climate, and systemic change. A case study is included to illustrate a school counseling department integrating a multi-tiered system of supports with their comprehensive school counseling program. In the case study, school counselors are described as interveners, facilitators and supporters regarding the implementation of a multi-tiered system of supports.

Keywords: multi-tiered system of supports, Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports, Response to Intervention, comprehensive school counseling programs, coordinated services

A multi-tiered system of supports (MTSS), including Response to Intervention (RTI) and Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports (PBIS), has been embedded in many public schools for the last decade. Specifically, these data-driven frameworks promote positive student academic and behavioral outcomes, as well as safe and favorable school climates (Ockerman, Mason, & Hollenbeck, 2012; Sugai & Horner, 2009). School counselors design and implement comprehensive school counseling programs that promote students’ academic, career, social, and emotional success as well as equitable student outcomes and systemic changes (American School Counselor Association [ASCA], 2012). As school leaders, school counselors should understand MTSS and play a leadership role in the development and implementation of such frameworks (ASCA, 2014; Goodman-Scott, 2014; Goodman-Scott, Betters-Bubon, & Donohue, 2016).

In a 2014 position statement on MTSS, ASCA described school counselors as important stakeholders in its implementation plan, stating “professional school counselors align their work with MTSS through the implementation of a comprehensive school counseling program designed to improve student achievement and behavior” (p. 38). Several scholars have discussed the alignment of RTI and comprehensive school counseling programs (Gruman & Hoelzen, 2011; Ockerman et al., 2012; Ryan, Kaffenberger, & Carroll, 2011; Ziomek-Daigle & Heckman, under review) as well as PBIS and comprehensive school counseling programs (Donohue, 2014; Goodman-Scott, 2014; Goodman-Scott et al., 2016; Shepard, Shahidullah, & Carlson, 2013), including school counselors’ roles in both. However, there remains a need to examine MTSS as an overarching construct and its overlap with comprehensive school counseling programs. In this article, we present information on MTSS, including RTI and PBIS, discuss comprehensive school counseling programs and the overlap of the two frameworks, and culminate with a case study illustrating the role of school counselors as interveners, facilitators, and supporters integrating MTSS and comprehensive school counseling programs in a middle school.

Multi-Tiered System of Supports

The use of MTSS offers school counselors opportunities to have a lasting impact on student academic success and behavior development while integrating these frameworks with comprehensive school counseling programs. MTSS, often used as an overarching construct for PBIS and RTI, is a schoolwide, three-tiered approach for providing academic, behavioral and social supports to all students based on their needs and skills (Cook, Lyon, Kubergovic, Wright, & Zhang, 2015; Harlacher, Sakelaris, & Kattelman, 2014; Sugai & Horner, 2009; Sugai & Simonsen, 2012). Harlacher et al. (2014) described six key tenets of the MTSS framework: (a) all students are capable of grade-level learning with adequate support; (b) MTSS is rooted in proactivity and prevention; (c) the system utilizes evidence-based practices; (d) decisions and procedures are driven by school and student data; (e) the degree of support given to each student is based on their needs; and (f) implementation occurs schoolwide and requires stakeholder collaboration.

MTSS consists of a continuum of three tiers of prevention: primary, secondary, and tertiary (Harlacher et al., 2014; Sugai & Horner, 2009). In Tier 1, or primary prevention, all students receive academic and behavioral support (Harlacher et al., 2014). Approximately 80% of students in a school are successful while receiving only primary prevention, or the general education academic and behavioral curriculum for all students. Examples include teaching expected behaviors schoolwide and the use of evidence-based academic strategies and curriculums. Students with elevated needs receive more specialized secondary and tertiary prevention, typically 15% and 5% of students, respectively (Harlacher et al., 2014; Sugai & Horner, 2009). Educators provide increasing degrees of interventions and supports in order for each student to be successful academically and behaviorally.

In regards to prevention, students are usually screened using academic benchmark assessments and behavioral data to determine their level of need (Harlacher et al., 2014; Sugai & Horner, 2009; Sugai & Simonsen, 2012). Some schools have moved to the use of universal screening to identify students with emerging mental health needs such as anxiety and depression (Lane, Oakes, & Menzies, 2010). Those with elevated needs receive interventions and are monitored to determine their progress and the interventions’ effectiveness. Further, the prevention activities in all three tiers are evidence-based practices (e.g., scientifically-based interventions; Harlacher et al., 2014; Sugai & Horner, 2009) and data-driven. Specifically, data is used to determine students’ needs and to measure progress. In the next section, two examples of MTSS will be discussed: RTI and PBIS.

Response to Intervention

The No Child Left Behind Act (2002) clearly emphasized that educators have unique opportunities to provide early intervention, quality instruction and data-driven decisions for all students. RTI, an outcome of the accountability movement, is “a systematic and structured approach to increase the efficiency, accountability, and impact of effective practices” (Crockett & Gillespie, 2007, p. 2). This framework was designed in 2004 as an alternative to states’ use of the discrepancy model of special education assessment, which compared children’s current ability and achievement levels (Ryan et al., 2011). By using only the discrepancy model to identify students in need of special education services, inconsistencies prevailed among school districts and states. Concerns about the discrepancy model included: (a) students of color were being over-identified as being in need of special education services as compared to White peers; (b) difficulty determining if low achievement was due to a possible learning disability or inadequate teacher performance; (c) educators waiting for students to fail instead of proactively identifying discrete literacy and numeracy skills that merited remediation (Fuchs & Fuchs, 2006). As RTI has evolved over the years, educators expanded the model to include behavioral and social interventions that are universal (e.g., whole-school) as well as intensive services (e.g., individual or small group), more fully responding to students with varied development.

RTI is currently used in school systems as a way to decrease referrals for special education services (Gersten & Dimino, 2006). The framework and the use of tiered supports ensure that students receive the appropriate level of intervention needed (Fuchs & Fuchs, 2006). Previously, students who exhibited difficulties in a single academic area would be referred to special education services, potentially removing them from the general education classroom. With RTI implementation, students now receive supports that allow them to remain in the general education classroom and reduce the rate of unnecessary referrals for special education services (Gersten & Dimino, 2006). RTI can be further described as instructional and behavioral.

Instructional RTI

Most educators report having a thorough knowledge of RTI to establish early literacy and math fluency and to provide additional supports in academic areas where needed (Shepard et al., 2013). Instructional RTI often is used to describe the process in which teachers work with students to mitigate the labeling and negative effects often associated with learning disabilities (Johnston, 2010). The teacher tailors the instruction to address the perceived deficit the student is exhibiting. Most often this delivery is used in the context of reading instruction (Shinn, 2010). The focus on instructional practice can take place on the first tier with whole class instruction, on the second tier with a small reading group, or on the third tier with intensive one-on-one instruction (Fuchs & Fuchs, 2006).

Behavioral RTI

Students may not only struggle with academic challenges, but behavioral, social and emotional challenges as well. Many students experience a host of challenging situations occurring in their homes and communities, such as poverty, homelessness, immigration and residency barriers, and the lack of fulfillment of basic needs such as adequate nutrition, transportation, and medical care (Shepard et al., 2013). Supporting social behavior is central for students to achieve academic gains, although this area is not often represented in traditional RTI implementation that may focus primarily on learning and instruction. More recent RTI frameworks reveal pyramids split in half showing both the academic and behavioral domains, more fully recognizing the complex entanglement between academic, social and emotional learning (Stormont, Reinke, & Herman, 2010). Behavioral RTI emphasizes a continuum of services that can be provided to students by school counselors and integrated into comprehensive school counseling programs.

A hallmark of both the instructional and behavioral RTI models is the focus on differentiation among the three tiers of intervention. Each approach delimits critical factors and components at the primary levels; interventions become more intense and personalized as students are provided more individualized supports. As with any type of intervention, data tracking is necessary to the success of the outcome (Utley & Obiakor, 2015). Both instructional and behavioral RTI use a system of data tracking known as continuous regeneration, in which the data is analyzed on an ongoing basis and interventions are evaluated based on recorded outcomes (McIntosh, Filter, Bennett, Ryan, & Sugai, 2010). The use of continuous regeneration means students receive the most applicable form of intervention throughout the course of their academic career. The following section will discuss the use of the RTI within school counseling programs.

School Counseling and RTI

Researchers have discussed the school counselor’s role and involvement in the RTI process (Ockerman et al., 2012; Ryan et al., 2011). Studies reveal that school counseling interventions using tiered approaches, such as universal instruction via classroom guidance programming and subsequent small group follow-up, have increased student achievement and motivation (Luck & Webb, 2009; Ryan et al., 2011). Ziomek-Daigle and Cavin (2015) discussed that positive behavior support strategies, which can be designed for students with behavioral issues in classrooms or at home, can be taught to teachers and parents for children who need more individualized support and monitoring. Additionally, school counselors have been identified as integral members to RTI teams by using behavioral observations to determine the responsiveness and effectiveness of services (Gruman & Hoelzen, 2011).

Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports

PBIS, a multi-tiered system of supports, is grounded in the principles of applied behavior analysis (Johnston, Foxx, Jacobson, Green, & Mulick, 2006) and implemented in over 21,000 schools across the United States (Sugai, 2016). Further, PBIS is often described as a function of RTI, including the “application of RTI principles to the improvement of social behavior outcomes for all students” (Sugai & Simonsen, 2012, p. 4). Thus, PBIS uses the three-tiered preventative continuum of data-driven and evidence-based practices to improve students’ academics and social behaviors (Sugai & Horner, 2009; Sugai & Simonsen, 2012). PBIS is implemented schoolwide, including evidence-based primary prevention for all students, and secondary and tertiary prevention for students with elevated needs (Shepard et al., 2013). Examples of primary prevention include universal behavioral expectations, discipline procedures, and acknowledgements, also known as positive reinforcement. Secondary and tertiary prevention can include behavioral contracts, social skill instruction and wraparound services.

One appealing aspect of PBIS is the use of systematic data collection for monitoring student referrals as well as PBIS implementation and fidelity (Simonsen & Sugai, 2013). Thus, data is used to continually determine student and school needs and related progress, and to guide future decisions in an iterative cycle. Examples of student data utilized include suspensions and office discipline referrals, grades, attendance, and other student outcomes (Sugai & Horner, 2009). Student data is often analyzed for patterns in office discipline referrals, such as frequency, location and time of year. Patterns can be analyzed using tools such as the School Wide Information System , a web-based tool for organizing and analyzing office discipline referral trends (May et al., 2006). Standardized assessments can be used to determine schoolwide data trends, including the School Wide Evaluation Tool, a research-validated instrument that measures the degree of PBIS implementation (Todd et al., 2012).

A plethora of researchers have demonstrated the positive impact of PBIS implementation as related to a number of school, student and staff benefits. Schools implementing PBIS have demonstrated better student academic outcomes (Horner et al., 2009; Simonsen et al., 2012), a decrease in student discipline incidences (Bradshaw, Mitchell, & Leaf, 2010; Bradshaw, Waasdorp, & Leaf, 2012; Curtis, Van Horne, Robertson, & Karvonen, 2010; Sherrod, Getch, & Ziomek-Daigle, 2009; Simonsen et al., 2012), and a more positive and safer school climate and work environment (Bradshaw, Koth, Bevans, Ialongo, & Leaf, 2008; Horner et al., 2009; Waasdorp, Bradshaw, & Leaf, 2012).

School Counseling and PBIS

Several scholars have discussed school counselors’ roles in PBIS implementation. Goodman-Scott et al. (2016) described the alignment between comprehensive school counseling programs and PBIS, particularly the use of data-driven, evidence-based practices and a tiered continuum of supports: prevention for all students and intervention for students with elevated needs. Further, through case studies, several researchers have demonstrated school counselors’ roles in PBIS implementation in their schools. Specifically, Sherrod et al. (2009) found a decrease in schoolwide and small group office discipline referrals and described school counselors’ roles in creating and implementing schoolwide interventions addressing student behaviors. Further, school counselors utilized student outcome data generated by the PBIS team to determine students’ needs for and progress in school counselor interventions such as small group counseling (Goodman-Scott, Hays, & Cholewa, under review). While in PBIS leadership roles, school counselors have demonstrated collaboration and consultation with stakeholders, contributed to a safe school environment and schoolwide systems of reinforcement, utilized student outcome data, implemented universal screening, facilitated PBIS-specific bullying prevention and conducted small group interventions (Curtis et al., 2010; Donohue, 2014; Donohue, Goodman-Scott & Betters-Bubon, 2016; Goodman-Scott, 2014; Goodman-Scott, Doyle, & Brott, 2014; Martens & Andreen, 2013).

PBIS and Behavioral RTI

Behavioral RTI and PBIS, although similar in their focus on schoolwide behaviors within a three-tiered framework, are remarkably different. First, all students are exposed to behavioral RTI, but only students who attend schools implementing PBIS receive the behavioral supports of the latter. The implementation and mandate of RTI is a direct outcome of the No Child Left Behind Act (2002). On the other hand, PBIS, a manualized approach, requires ongoing training and a specific evaluation process. PBIS fidelity is necessary for successful implementation and requires ongoing data collection and analysis. The behavioral RTI approach allows schools to design and develop their own frameworks in a contextual manner to best support their students, and the method and training for implementation remains flexible. School counselors can be active in both RTI and PBIS implementation in their schools, as several of these roles overlap with comprehensive school counseling programs.

Comprehensive School Counseling Programs

Comprehensive school counseling programs were initially conceptualized in the 1960s and 1970s, have evolved over time, are tied to the school’s academic mission, and are based on student competencies in the academic, career, social and emotional domains (Gysbers & Henderson, 2012). One well-known and widely used comprehensive school counseling framework is the ASCA National Model (ASCA, 2012; Gysbers & Henderson, 2012). The model was based on (a) the ASCA National Standards for School Counseling Programs , which defined student standards and competencies regarding academic, career, personal and social development (Campbell & Dahir, 1997), and (b) the Education Trust’s Transforming School Counseling Initiative , which emphasized school counselors’ roles in closing the achievement gap for low-income and minority students, and performing leadership, advocacy, systemic change, and collaboration and teaming (Martin, 2015). The model was created in 2003, was updated in both 2005 and 2012, and has provided the school counseling professional with a unified vision, voice, and identity in regards to the school counselors’ roles (ASCA, 2012; Gysbers & Henderson, 2012).

Many scholars have reported positive outcomes related to comprehensive school counseling program implementation. For example, Wilkerson, Pérusse, and Hughes (2013) found that elementary schools designated as fully implemented ASCA Model Programs had higher standardized English and Language Arts and Math scores than those schools without the designation. Similarly, other scholars have associated comprehensive school counseling program implementation with higher student achievement scores (Sink, Akos, Turnbull, & Mvududu, 2008; Sink & Stroh, 2003). In a similar vein, Hatch, Poynton, and Pérusse (2015) reported that the increased national emphasis on comprehensive school counseling programs over the last decade has positively impacted school counselors’ related beliefs and priorities.

The ASCA National Model and a Multi-Tiered System of Supports

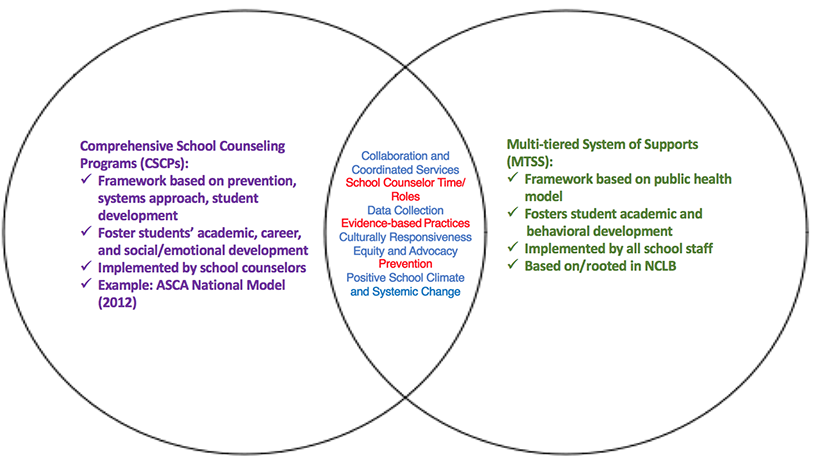

School counselors are crucial in students’ learning and social development and are invested in early interventions that are at the root of comprehensive school counseling programs (Ryan et al., 2011). MTSS aligns with the ASCA National Model’s chief inputs of advocacy, collaboration, systemic change, prevention, intervention and the use of data. Thus, both the ASCA National Model (2012) and MTSS are inherently connected given their overlapping foci (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Overlap and similarities between a multi-tiered system of supports and comprehensive school counseling programs

Overlap exists between these two frameworks, especially prominent when school counselors take on roles as supporters, interveners and facilitators in offering indirect as well as direct services (Ockerman et al., 2012; Ziomek-Daigle & Heckman, under review). In the role as supporters, school counselors share data related to interventions, discuss needs assessment data and increase awareness regarding equity gaps that may be present at the school (Ockerman et al., 2012). School counselors are interveners and facilitators as active members of RTI teams who provide behavioral interventions and services and, through progress monitoring, collect and review data and make recommendations (Ockerman et al., 2012; Ziomek-Daigle & Heckman, under review).

The ASCA National Model (2012) provides the necessary components for comprehensive school counseling programs grounded in student data and based on student academic, career, social and emotional development. The model includes four components: foundation, delivery, management, and accountability. Next, we discuss the integration of a multi-tiered system of supports into the four components of the model.

Foundation. Establishing the program’s foundation is the initial step in building a comprehensive school counseling program (ASCA, 2012). As programs are developed, school counselors should examine their own personal beliefs about their role with students. Program mission and vision statements should also be created, using measurable language. Additionally, student competencies in the academic, career, social and emotional domains are reflected in comprehensive programs along with school counselors’ ethical decision making and professional practice. School counselors’ program visions and goals should reflect priorities also highlighted in the school’s multi-tiered framework (Goodman-Scott et al., 2016). For example, Goodman-Scott et al. (2016) suggested school counselors’ vision and mission statements should represent school and district current trends and goals, such as PBIS delivery and implementation.

Delivery. The delivery component of the framework identifies the types of services that school counselors directly offer students such as classroom guidance programming and core curriculum (Ziomek-Daigle, 2015), individual student planning, small group and individual counseling, consultation, and referral (ASCA, 2012). Many approaches used within a multi-tiered system of supports also can be utilized within the delivery system of school counseling programs, such as prevention activities (e.g., teaching schoolwide expectations in classroom guidance programming) and interventions (e.g., check in/check out; Goodman-Scott et al., 2016; Goodman-Scott et al., under review; Ziomek-Daigle & Heckman, under review). Further, school counselors can integrate more intensive interventions for students with multiple, complex needs, including wraparound services (Shepard et al., 2013).

Accountability and Management. Accountability and management are at the root of any comprehensive school counseling program, as data is collected, analyzed and reported, identifying how students are different as a result of the program (ASCA, 2012). Further, school counselors utilize a variety of tools and assessments to gather evidence of program and school counselor effectiveness (ASCA, 2012). Data generated from a multi-tiered system of supports, such as student achievement and behavior, are continuously collected and reviewed to determine student needs and intervention effectiveness. School counselors can use this data from a multi-tiered system of supports to determine student and school needs and create curriculum, small group and closing-the-gap action plans accordingly (Goodman-Scott et al., 2016). After implementing interventions, school counselors can measure the impact of their interventions on the desired student outcomes including attendance, office referrals and grades, thus determining their effectiveness and impact through the use of result reports. MTSS overlaps with comprehensive school counseling programs; thus, the two can be integrated to strengthen both. The following section discusses the commonalities between MTSS and comprehensive school counseling programs.

Commonalities Between a Multi-Tiered System of Supports and Comprehensive School Counseling Programs

Several similarities exist between MTSS and comprehensive school counseling programs (see Figure 1). Similarities include utilizing collaboration and coordinated services; efficiently using the school counselors’ time through tiered supports; collecting and reviewing student and school data; using evidence-based practices; developing culturally responsive interventions that close achievement gaps; promoting prevention and intervention for students through a tiered continuum; and facilitating schoolwide systemic change and a positive school climate. First, both frameworks have established leadership teams that guide program design and implementation, represent the stakeholders within the building and offer support in program development and accessing resources. Next, tiered approaches provide school counselors time to address whole-school needs while also providing services to and advocating on behalf of students in crisis or with significant needs. Thus, using tiered approaches may assist school counselors directly and indirectly serve students. Ongoing progress monitoring through continuous data collection keeps MTSS and comprehensive school counseling programs focused and stakeholders informed, which may lead to greater stakeholder awareness and support for school counseling initiatives. Similarly, the use of evidence-based practices, recommended by MTSS and comprehensive school counseling, offers students quality, empirically-backed academic and behavioral services across all three tiers. A successful MTSS also allows school counselors to address achievement gaps and increase equitable practices by strengthening social supports for students in the classroom, school building and community who present with challenging behavior. A case study illustrating the role of school counselors as interveners, facilitators and supporters of integrating both MTSS and comprehensive school counseling programs follows.

Example Middle School (EMS) is located in a suburban setting with approximately 700 students across sixth, seventh and eighth grades; 25% of students come from households considered economically disadvantaged. The majority of students identify as Caucasian (45%) or African American (30%). RTI has been implemented in EMS for approximately seven years, while PBIS has been implemented for four years. The school administration consists of one principal and three assistant principals (APs), and the school counseling department includes three school counselors with a school counselor to student ratio of 1:233. Each grade level is assigned one AP and one school counselor.

The grade levels each meet bi-weekly to discuss academic planning and share information regarding students (both concerns and accomplishments). The EMS student support team is an interdisciplinary team that meets to create and discuss academic and behavioral interventions and related progress for students demonstrating consistent academic and behavioral challenges that were not successfully addressed by the grade-level Tier 1 meetings. The student support team is facilitated by a teacher and attended by the grade-level AP and school counselor as well as the school psychologists. Parents of the reviewed student also are invited. In addition, EMS has a PBIS team comprised of representatives from all grade levels and specialties, including one school counselor; parents and students are represented on the PBIS team. The school counselor and AP together oversee the PBIS data collection and analysis. Lastly, the school counseling team meets weekly and over the last seven years has developed a comprehensive school counseling program based on the ASCA National Model. All school counselors at EMS have essential roles in the program implementation.

The school counselors act as supporters, interveners and facilitators in Tier 1. As supporters, EMS school counselors attend all regular grade-level meetings and provide background information on students as appropriate. As interveners, school counselors collaborate and consult with teachers on their instruction and curriculum as well as teachers’ monitoring and screening of all students to identify those with elevated academic and behavioral needs. For example, at the most recent seventh-grade-level meeting, the school counselor reviewed grade-level office discipline referrals, attendance records and teachers’ anecdotal feedback. The grade-level team expressed concern about a student, Elena, who had several absences and office discipline referrals in the last month. The seventh-grade school counselor provided non-confidential background information on Elena to the grade-level team members.

The school counselor on the PBIS team holds a number of additional roles as supporter. First, the counselor provides information on school climate generated by the comprehensive school counseling program, including both anecdotal observations and data-driven findings. The school counselor also assists the PBIS team in developing a common school language and protocols (i.e., school expectations: Be Responsible, Be Respectful, Be Safe), schoolwide and individual acknowledgements for students and staff, and discipline procedures (i.e., the office discipline referral process). In the role as facilitator, the school counselors assist the PBIS team as they plan schoolwide pep rallies to further teach the school expectations, acknowledge students, classes and staff with certain achievements (e.g., the homeroom with the lowest office discipline referrals per quarter; staff who distributed the highest number of school tickets). As an intervener, all school counselors teach the PBIS-generated school expectations during their regular monthly classroom lessons and engage in student acknowledgements (e.g., distributing EMS tickets for positive behaviors). Intervener roles also include school counselors engaging in student advising and schoolwide programming, such as teaching students and staff the bullying prevention strategies from Expect Respect , an evidence-based bully prevention program (Stiller, Nese, Tomlanovich, Horner, & Ross, 2013). Additionally, in roles as interveners, school counselors deliver a social skills curriculum to students during weekly homeroom advisory periods or through regular guidance lessons (Ziomek-Daigle, 2015). Further, school counselors collaborate with school psychologists to engage in universal mental health screening for student depression and anxiety and provide evidence-based classroom lessons to all students to promote positive mental health, as interveners (Donohue et al., 2016).

The school counseling program holds advisory team meetings quarterly. Members include all school counselors, a student and parent representative, a general education teacher from all grade levels, the PBIS coach, the AP who reviews PBIS data and one special education teacher. At the end of each year, the advisory team reviews a number of data points, including the comprehensive school counseling program goals from the previous year and related outcomes and results reports, schoolwide PBIS behavioral data, RTI instructional and behavioral data, and the school data profile. Next, the advisory team makes goals for the subsequent year based on data-determined needs. Then, based on the advisory team’s recommendations, the school counselors create closing-the-gap action plans and goals for the next year (i.e., SMART goals,). School counselors present the results of their advisory team meetings, action plans, SMART goals, and results reports to the administrative team (principal and APs), as well as the PBIS team, RTI team and whole school faculty.

Tiers Two and Three

When providing Tier 2 and 3 supports and services, the EMS school counselors engage in supporter, interventionist and facilitator roles. To follow up from the grade-level meetings, the EMS school counselors act as interveners by consulting and collaborating with teachers individually regarding evidence-based academic and behavioral interventions for struggling students as well as teachers’ classroom management. As part of the PBIS team, the school counselor acts as a supporter by discussing schoolwide behavioral trends, students with elevated office discipline referrals, and students who are otherwise considered at risk (e.g., absences, class failures, poor standardized and benchmark tests) and recommending interventions. One intervention may be referral to the student support team.

In a role as supporter, school counselors attend the student support team meetings and, along with this team, recommend increasingly individualized evidence-based student academic and behavioral interventions and monitor students’ progress at subsequent meetings. Tier 3 interventions are greater in duration and intensity than Tier 2 and have greater individualization. The student support team works together to identify students in need of Tier 2 or Tier 3 interventions, facilitates service implementation and decides to decrease and end interventions due to students maintaining positive progress. The student support team recommends interventions which may include individual or small group counseling and function-based behavioral mentoring interventions such as Check In, Check Out and Check & Connect (Baker & Ryan, 2014). As interveners, school counselors often provide counseling and mentoring or coordinate other staff and community members’ involvement in mentoring programs. In addition, the school counselor may be trained to use the Check & Connect program and continuously review attendance, behavioral and academic data (i.e., check) and provide interventions (i.e., connect) to a small caseload of students who are being served through Tier 2 and 3 services. As facilitators, school counselors also may develop and access a list of health care providers so that students and families participate in a seamless referral process. In this role, counselors also may coordinate quarterly interdisciplinary meetings for a few students whose needs are complex and who receive community-based agency assistance. Some examples of interdisciplinary collaborative team members include: school counselors, mental health counselors, psychologists, nurses, probation officers and case workers. Lastly, the EMS school counselors, acting as interveners and facilitators, analyze the results of the universal mental health screener for depression and anxiety.

In regards to student Elena, the seventh-grade school counselor and grade-level team agreed that the school counselor would meet with Elena individually to gather additional background information on her absences and office discipline referrals. When Elena did not improve over the subsequent two-week period, more intensive and continued interventions were discussed with the grade-level team, including a referral to the student support team. After review by the student support team, Elena began Check & Connect with the school counselor, and the school counselor maintained communication with Elena’s mother and stepfather, teachers and members of the student support team.

ASCA (2014) recommends that school counselors can implement MTSS in alignment with facilitating a comprehensive school counseling program. Further, several scholars have contended that school counselors can be leaders in MTSS, incorporating these duties into aspects of a comprehensive school counseling program (Cressey, Whitcomb, McGilvray-Rivet, Morrison, & Shander-Reynolds, 2014; Goodman-Scott et al., 2016). As described in this article, MTSS and comprehensive school counseling programs share many overlapping characteristics, and school counselors may act as leaders in both, vacillating between the roles of supporter, intervener and facilitator (Ockerman et al., 2012; Ziomek-Daigle & Heckman, under review). In implementing both frameworks, school counselors are able to focus on student achievement and behavior, as well as collaboration, data collection, evidence-based practices and social justice advocacy, to close achievement and equity gaps. Additionally, school counselors can utilize the existing MTSS in the schools to enhance, expand and challenge their own comprehensive programs and present new, relevant and critical research and practical implications to the field. Goodman-Scott et al. (2016) suggested that aligning both frameworks may be a strategy to advocate at local and national levels for the school counseling field and comprehensive school counseling program implementation. Presenting school counseling programs in this manner also can increase stakeholder involvement, access additional resources and increase job stability. Focusing on the overlap between MTSS and comprehensive school counseling programs leads to a data-driven, evidence-based focus on improving school climate, as well as student equity, access, and academic and behavioral success, meeting the needs of students across all three tiers.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The authors reported no conflict of interest

or funding contributions for the development

of this manuscript.

American School Counselor Association. (2012). The ASCA national model: A framework for school counseling programs (3rd ed.). Alexandria, VA: Author.

American School Counselor Association. (2014). The professional school counselor and multitiered system of supports. American School Counselor Association Position Statement. Retrieved from https://www.school counselor.org/asca/media/asca/PositionStatements/PS_MultitieredSupportSystem.pdf

Baker, B., & Ryan, C. (2014). The PBIS team handbook: Setting expectations and building positive behavior. Minneapolis, MN: Free Spirit Publishing.

Bradshaw, C. P., Koth, C. W., Bevans, K. B., Ialongo, N., & Leaf, P. J. (2008). The impact of school-wide positive behavioral interventions and supports (PBIS) on the organizational health of elementary schools. School Psychology Quarterly , 23 , 462–473. doi:10.1037/a0012883

Bradshaw, C. P., Mitchell, M. M., & Leaf, P. J. (2010). Examining the effects of schoolwide positive behavioral interventions and supports on study outcomes: Results from a randomized controlled effectiveness trial in elementary schools. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions , 12 , 133–148. doi:10.1177/1098300709334798

Bradshaw, C. P., Waasdorp, T. E., & Leaf, P. J. (2012). Effects of school-wide positive behavioral interventions and supports on child behavior problems. Pediatrics , 130 , 1136–1145. doi:10.1542/peds.2012-0243

Campbell, C. A., & Dahir, C. A. (1997). Sharing the vision: The national standards for school counseling programs. Alexandria, VA: American School Counselor Association.

Cook, C. R., Lyon, A. R., Kubergovic, D., Wright, D. B., & Zhang, Y. (2015). A supportive beliefs intervention to facilitate the implementation of evidence-based practices within a multi-tiered system of supports. School Mental Health , 7 , 49–60. doi:10.1007/s12310-014-9139-3

Cressey, J. M., Whitcomb, S. A., McGilvray-Rivet, S. J., Morrison, R. J., & Shander-Reynolds, K. J. (2014). Handling PBIS with care: Scaling up to school-wide implementation. Professional School Counseling , 18 , 90–99. doi:10.5330/prsc.18.1.g1307kql2457q668

Crockett, J. B., & Gillespie, D. N. (2007, Fall). Getting ready for RTI: A principal’s guide to response to intervention. ERS Spectrum , 25 (4), 1–9.

Curtis, R., Van Horne, J. W., Robertson, P., & Karvonen, M. (2010). Outcomes of a school-wide positive behavioral support program. Professional School Counseling , 13 , 159–164. doi:10.5330/PSC.n.2010-13.159

Donohue, M. D. (2014). Implementing school wide positive behavioral supports (SWPBIS): School counselors’ perceptions of student outcomes, school climate, and professional effectiveness. Retrieved from http://digitalcommons.uconn.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=6616&context=dissertations

Donohue, P., Goodman-Scott, E., & Betters-Bubon, J. (2016). Using universal screening for early identification of students at risk: A case example from the field. Professional School Counseling , 19 , 133–143 . doi:10.5330/1096-2409-19.1.133

Fuchs, D., & Fuchs, L. S. (2006). Introduction to response to intervention: What, why, and how valid is it? Reading Research Quarterly , 41 , 93–99.

Gersten, R., & Dimino, J. A. (2006). RTI (Response to Intervention): Rethinking special education for students with reading difficulties (yet again). Reading Research Quarterly , 41 , 99–108. doi:10.1598/RRQ.41.1.5

Goodman-Scott, E. (2014). Maximizing school counselors’ efforts by implementing school-wide positive behavioral interventions and supports: A case study from the field . Professional School Counseling , 17 , 111–119. doi:10.5330/prsc.17.1.518021r2x6821660

Goodman-Scott, E., Betters-Bubon, J., & Donohue, P. (2016). Aligning comprehensive school counseling programs and positive behavioral interventions and supports to maximize school counselors’ efforts. Professional School Counseling , 19 , 57–67. doi:10.5330/1096-2409-19.1.57

Goodman-Scott, E., Doyle, B., & Brott, P. (2014). An action research project to determine the utility of bully prevention in positive behavior support for elementary school bullying prevention. Professional School Counseling , 17 , 120–129. doi:10.5330/prsc.17.1.53346473u5052044

Goodman-Scott, E., Hays, D. G., & Cholewa, B. (under review). “It takes a village:” A case study of positive behavioral interventions and supports implementation in an exemplary middle school.

Gruman, D. H., & Hoelzen, B. (2011). Determining responsiveness to school counseling interventions using behavioral observations. Professional School Counseling , 14 (3), 183–190. doi:10.5330/PSC.n.2011-14.183

Gysbers, N. C., & Henderson, P. (2012). Developing and managing your school guidance and counseling program (5th ed.). Alexandria, VA: American Counseling Association.

Harlacher, J. E., Sakelaris, T. L., & Kattelman, N. M. (2014). Practitioner’s guide to curriculum-based evaluation in reading. New York, NY: Springer.

Hatch, T., Poynton, T., & Pérusse, R. (2015). Comparison findings of school counselor beliefs about ASCA National Model school counseling program components using the SCPCS. SAGE Open, 1–10. doi:10.1177/2158244015579071

Horner, R. H., Sugai, G. M., Smolkowski, K., Eber, L., Nakasato, J., Todd, A. W., & Esperanza, J. (2009). A randomized, wait-list controlled effectiveness trial assessing school-wide positive behavior support in elementary schools. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions , 11 (3), 133–144. doi:10.1177/1098300709332067

Johnston, P. (2010). An instructional frame for RTI. The Reading Teacher , 63 , 602–604. doi:10.1598/RT.63.7.8

Johnston, J. M., Foxx, R. M., Jacobson, J. W., Green, G., & Mulick, J. A. (2006). Positive behavior support and applied behavior analysis. The Behavior Analyst , 29 , 51–74.

Lane, K. L., Oakes, W., & Menzies, H. (2010). Systematic screenings to prevent the development of learning and behavior problems: Considerations for practitioners, researchers, and policy makers. Journal of Disability Policy Studies , 21 (3), 160–172. doi:10.1177/1044207310379123

Luck, L., & Webb, L. (2009). School counselor action research: A case example. Professional School Counseling , 12 , 408–412.

Martens, K., & Andreen, K. (2013). School counselors’ involvement with a school-wide positive behavior support intervention: Addressing student behavior issues in a proactive and positive manner. Professional School Counseling , 16 , 313–322.

Martin, P. J. (2015). Transformational thinking in today’s schools. In B. T. Erford (Ed.), Transforming the school counseling profession (4th ed., pp. 45–65). Boston, MA: Pearson.

May, S., Ard, W., Todd, A. W., Horner, R. H., Glasgow, A., Sugai, G., & Sprague, J. R. (2006). School wide information system . Eugene: Educational and Community Supports, University of Oregon.

McIntosh, K., Filter, K. J., Bennet, J. L., Ryan, C., & Sugai, G. (2010). Principles of sustainable prevention: Designing scale-up of schoolwide positive behavior support to promote durable systems. Psychology in the Schools , 47 , 5–21. doi:10.1002/pits.20448

No Child Left Behind Act of 2001, P.L. No. 107–110. 115, Stat. 1425 (2002).

Ockerman, M. S., Mason, E. C. M., & Hollenbeck, A. F. (2012). Integrating RTI with school counseling programs: Being a proactive professional school counselor. Journal of School Counseling , 10 (15), 1–37.

Ryan, T., Kaffenberger, C. J., & Carroll, A. G. (2011). Response to intervention: An opportunity for school counselor leadership. Professional School Counseling , 14 , 211–221. doi:10.5330/PSC.n.2011-14.211

Shepard, J. M., Shahidullah, J. D., & Carlson, J. S. (2013). Counseling students in levels 2 and 3: A PBIS/RTI Guide. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Sherrod, M. D., Getch, Y. Q., & Ziomek-Daigle, J. (2009). The impact of positive behavior support to decrease discipline referrals with elementary students. Professional School Counseling , 12 , 421–427. doi:10.5330/PSC.n.2010-12.421

Shinn, M. R. (2010). Building a scientifically based data system for progress monitoring and universal screening across three tiers including RTI using Curriculum-Based Measurement. In M. R. Shinn & H. M. Walker (Eds.), Interventions for achievement and behavior problems in a three-tier model, including RTI (pp. 259–292).Bethesda, MD: National Association of School Psychologists.

Simonsen, B., Eber, L., Black, A. C., Sugai, G., Lewandowski, H., Sims, B., & Myers, D. (2012). Illinois statewide positive behavioral interventions and supports: Evolution and impact on student outcomes across years. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions , 14 , 5–16. doi:10.1177.1098300711412601

Simonsen, B., & Sugai, G. (2013). PBIS in alternative educational settings: Positive support for youth with high-risk behavior. Education and Treatment of Children , 36 , 3–14.

Sink, C. A., Akos, P., Turnbull, R. J., & Mvududu, N. (2008). An investigation of comprehensive school counseling programs and academic achievement in Washington state middle schools. Professional School Counseling , 12 , 43–53. doi:10.5330/PSC.n.2010-12.43

Sink, C. A., & Stroh, H. R. (2003). Raising achievement test scores of early elementary school students through comprehensive school counseling programs. Professional School Counseling , 6 , 350–364.

Stiller, B. C., Nese, R. N. T., Tomlanovich, A. K., Horner, R. H., & Ross, S. W. (2013). Bullying and harassment prevention in positive behavior support: Expect respect. Eugene: Educational and Community Supports, University of Oregon.

Stormont, M., Reinke, W. M., & Herman, K. C. (2010) . Introduction to the special issue: Using prevention science to address mental health issues in schools . Psychology in the Schools , 47 , 1–4.

Sugai, G. (2016). Positive behavioral interventions and supports [Powerpoint slides]. Retrieved from http://www.pbis.org/ Common/Cms/files/pbisresources/3%20Feb%202016%20SAfrica%20PBIS%20HAND%20gsugai.pdf

Sugai, G., & Horner, R. H. (2009). Responsiveness-to-intervention and school-wide positive behavior supports: Integration of multi-tiered system approaches. Exceptionality , 17 , 223–237. doi:10.1080/09362830903235375

Sugai, G., & Simonsen, B. (2012). Positive behavioral interventions and supports: History, defining features, and misconceptions . Retrieved from http://www.pbis.org/common/cms/files/pbisresources/PBIS_revisited_ June19r_2012.pdf

Todd, A. W., Lewis-Palmer, T., Horner, R. H., Sugai, G., Sampson, N. K., & Phillips, D. (2012). School wide evaluation (SET) implementation manual. Retrieved from http://www.pbis.org/common/cms/files/pbisresources/SET_M anual_02282012.pdf

Utley, C. A., & Obiakor, F. E. (2015). Special issue: Research perspectives on multi-tiered system of support. Learning Disabilities: A Contemporary Journal , 12 , 1–2.

Waasdorp, T. E., Bradshaw, C. P., & Leaf, P. J. (2012). The impact of schoolwide positive behavioral interven-tions and supports on bullying and peer rejection. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine , 166 , 149–156. doi:10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.755

Wilkerson, K., Pérusse, R., & Hughes, A. (2013). Comprehensive school counseling programs and student achievement outcomes: A comparative analysis of RAMP Versus Non-RAMP Schools. Professional School Counseling , 16 , 172–184. doi:10.5330/PSC.n.2013-16.172.

Ziomek-Daigle, J. (Ed.). (2015). School counseling classroom guidance: Prevention, accountability, and outcomes. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

Ziomek-Daigle, J., & Cavin, J. (2015). Shaping youth and families through positive behavior support: A call for counselors. The Family Journal , 23 , 386–373. doi:10.1177/1066480715601106

Ziomek-Daigle, J., & Heckman, B. (under review). Unpacking the behavioral Response to Intervention model for school counseling: Evidence-based practices across the tiers.

Jolie Ziomek-Daigle is an Associate Professor at the University of Georgia. Emily Goodman-Scott, NCC, is an Assistant Professor at Old Dominion University. Jason Cavin is the Director of Behavior Support and Consultation at the School of Public Health at Georgia State University and a doctoral candidate at the University of Georgia. Peg Donohue is an Assistant Professor at Central Connecticut State University. Correspondence can be addressed to Jolie Ziomek-Daigle, 402 Aderhold Hall, Athens, GA 30602, [email protected].

Recent Publications

- Examination of the Bystander Intervention Model Among Middle School Students: A Preliminary Study September 13, 2024

- Centering Social Justice in Counselor Education: How Student Perspectives Can Help September 13, 2024

- Adverse Childhood Experiences of Professional School Counselors as Predictors of Compassion Satisfaction, Burnout, and Secondary Traumatic Stress September 13, 2024

- Black People’s Reasons for Becoming Professional Counselors: A Grounded Theory September 13, 2024

Writing a Counselling Case Study

As a counselling student, you may feel daunted when faced with writing your first counselling case study. Most training courses that qualify you as a counsellor or psychotherapist require you to complete case studies.

Before You Start Writing a Case Study

However good your case study, you won’t pass if you don’t meet the criteria set by your awarding body. So before you start writing, always check this, making sure that you have understood what is required.

For example, the ABC Level 4 Diploma in Therapeutic Counselling requires you to write two case studies as part of your external portfolio, to meet the following criteria:

- 4.2 Analyse the application of your own theoretical approach to your work with one client over a minimum of six sessions.

- 4.3 Evaluate the application of your own theoretical approach to your work with this client over a minimum of six sessions.

- 5.1 Analyse the learning gained from a minimum of two supervision sessions in relation to your work with one client.

- 5.2 Evaluate how this learning informed your work with this client over a minimum of two counselling sessions.

If you don’t meet these criteria exactly – for example, if you didn’t choose a client who you’d seen for enough sessions, if you described only one (rather than two) supervision sessions, or if you used the same client for both case studies – then you would get referred.

Check whether any more information is available on what your awarding body is looking for – e.g. ABC publishes regular ‘counselling exam summaries’ on its website; these provide valuable information on where recent students have gone wrong.

Selecting the Client

When you reflect on all the clients you have seen during training, you will no doubt realise that some clients are better suited to specific case studies than others. For example, you might have a client to whom you could easily apply your theoretical approach, and another where you gained real breakthroughs following your learning in supervision. These are good ones to choose.

Opening the Case Study

It’s usual to start your case study with a ‘pen portrait’ of the client – e.g. giving their age, gender and presenting issue. You might also like to describe how they seemed (in terms of both what they said and their body language) as they first entered the counselling room and during contracting.

If your agency uses assessment tools (e.g. CORE-10, WEMWBS, GAD-7, PHQ-9 etc.), you could say what your client scored at the start of therapy.

Free Handout Download

Writing a Case Study: 5 Tips

Describing the Client’s Counselling Journey

This is the part of the case study that varies greatly depending on what is required by the awarding body. Two common types of case study look at application of theory, and application of learning from supervision. Other possible types might examine ethics or self-awareness.

Theory-Based Case Studies

If you were doing the ABC Diploma mentioned above, then 4.1 would require you to break down the key concepts of the theoretical approach and examine each part in detail as it relates to practice. For example, in the case of congruence, you would need to explain why and how you used it with the client, and the result of this.

Meanwhile, 4.2 – the second part of this theory-based case study – would require you to assess the value and effectiveness of all the key concepts as you applied them to the same client, substantiating this with specific reasons. For example, you would continue with how effective and important congruence was in terms of the theoretical approach in practice, supporting this with reasoning.

In both, it would be important to structure the case study chronologically – that is, showing the flow of the counselling through at least six sessions rather than using the key concepts as headings.

Supervision-Based Case Studies

When writing supervision-based case studies (as required by ABC in their criteria 5.1 and 5.2, for example), it can be useful to use David Kolb’s learning cycle, which breaks down learning into four elements: concrete experience, reflective observation, abstract conceptualisation and active experimentation.

Rory Lees-Oakes has written a detailed guide on writing supervision case studies – entitled How to Analyse Supervision Case Studies. This is available to members of the Counselling Study Resource (CSR).

Closing Your Case Study

In conclusion, you could explain how the course of sessions ended, giving the client’s closing score (if applicable). You could also reflect on your own learning, and how you might approach things differently in future.

- Browse by Subjects

- New Releases

- Coming Soon

- Chases's Calendar

- Browse by Course

- Instructor's Copies

- Monographs & Research

- Intelligence & Security

- Library Services

- Business & Leadership

- Museum Studies

- Pastoral Resources

- Psychotherapy

Contemporary Case Studies in School Counseling

Edited by marguerite ohrtman and erika heltner, also available.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Download Free PDF

The most common cases and counseling approaches in school counseling

The aim of this study is to find out numerous situations and counseling approaches that school counselors are likely to encounter during their training and the first five years of practice. We believe that attention to the various theoretical approaches that can be applied to resolve different cases will better prepare school counselors to deal with each dilemma using an efficient approach to school counseling. Thus it is important to know the most common cases seen and counseling approaches used in school counseling to prepare school counseling students to the profession. In order to achieve data about school counseling cases and approaches, fourteen high school counselors from public and private schools are interviewed with semi structured questionnaire prepared by researchers. School counselors are asked about the cases that they see the most, the approaches that they use with these cases, support systems that they seek for and therapy trainings that they take after their graduation from college. Study group is settled with random sampling from schools in different districts of Istanbul that have school counselor with at least one year experience. The results are analyzed with thematic analysis.

Related papers

Global Journal of Guidance and Counseling in Schools: Current Perspectives, 2017

The aim of this study is to find out numerous situations and counseling approaches that school counselors are likely to encounter during their training and the first five years of practice. We believe that attention to the various theoretical approaches that can be applied to resolve different cases will better prepare school counselors to deal with each dilemma using an efficient approach to school counseling. Thus it is important to know the most common cases seen and counseling approaches used in school counseling to prepare school counseling students to the profession. In order to achieve data about school counseling cases and approaches, fourteen high school counselors from public and private schools are interviewed with semi structured questionnaire prepared by researchers. School counselors are asked about the cases that they see the most, the approaches that they use with these cases, support systems that they seek for and therapy trainings that they take after their graduat...

Over time the term counseling has been used and studied from different approaches and defined in different ways according to the researches and the field of study. As a huge concept it covers three main areas: personal, educational and vocational area, that’s for we have different definitions about counseling. In educational level for long time it have been confusion about the role and importance of school counseling, where for some researches it was defined and studied as part of school Guidance program and addressed to other school staff, minimizing the role of counselor. In other hand other approaches tend to use and understand the schoolcounseling as synonymous for Guidance meanwhile others viewed as profession that is part of psychological and psychotherapeutic nature. Now day’s the counseling as profession is more emphases and school counseling takes its place in all educational level. Today school counseling is a need and necessary in every level of education taking in consideration the role and importance that has on educational process and school program overall. Keywords: Counseling, School Counseling, School Counselor, Role of School Counselor

BCES Conference Books, 2020

This paper presents results of a comparative international study on some aspects of school counseling in the following 12 countries: Austria, Bulgaria, Croatia, Denmark, Ireland, Malta, North Macedonia, Russia, Serbia, Slovenia, UK, and USA. The authors explain the multi-functional character of school counseling, give an idea of establishing a research field that could be called 'comparative school counseling studies', show the original terms in individual countries, and compare six aspects of school counseling: 1) legislative framework; 2) position requirements; 3) role of school counselors; 4) functions of school counselors; 5) interaction; and 6) ratio. The paper concludes with a long list of qualities school counselors are expected to possess. This is a document study chiefly based on examining, systematizing and comparing national documents (laws, reports, instructions, advices, position requirements, ministerial orders, recommendations, strategies, and statistics) on s...

The Journal of Academic Social Sciences, 2023

The aim of this study is to examine the perceptions of middle school counsellors about their counselling experiences in their schools. The data of this study, which was carried out with the qualitative research method, were collected through semi-structured interview questions from 6 psychological counsellors working in middle school in Istanbul. From the interviews with the participants: “Students' Access to School Counselor”, “The Issues Students Have Needed Support”, “Addressing Students’ Expectations”, “Competence Perception of School Psychological Counsellors”, “Cooperation with Others”, “Main Challenges in School Counselling Process” and “Alternative Support Routes” main themes were obtained. While the data of this research was collected by the researcher within the scope of her master’s thesis in 2013, the findings were discussed together with the results of current studies investigating the professional experiences of school counsellors in Turkey. In line with the findings, suggestions were made to contribute to the improvement of school psychological counseling services.

This article covers the characteristics that are supposed to be present in the practicum of school-based counseling in Turkey. In the light of the related literature, 11 characteristics are determined. These are the place of practicum, the importance of official permission for the school, the characteristics of practicum schools and its school counselors, supervisory meetings and supervisors, the time of the applications and the institutions that the practicum will take place, developing a counseling program, the administration of self-report techniques, group and classroom guidance activities, career guidance, consultation and assessing the counseling program. The last section includes the results and the suggestions for further research.

This paper discusses the need for counseling services in schools in a holistic manner in line with the current era of globalization and the industrial revolution. Guidance and counseling services are important aspects of the school system. Counseling services are not just for students who are involved in disciplinary issues, but also for the positive development of individuals. To be effective counselors in helping students, especially in this era of globalization, counselors need current knowledge in the field of counseling. In Malaysia, most school counselors have been trained in a special counseling training program. Most counselors who are providing counseling services in high school have a first degree (Bachelor’s) in the counseling field and some even specialize further with a Master’s. In line with the Malaysian Counselor's Act (Act 580), many of the school counselors have been registered with the Board of Counselors to practice professionally. Schools have also been prov...

Aim: Qualitative and quantitative development of counseling program in education system can be regarded as an indicator of development in education system. The present research was conducted in schools with the aim of identifying the damaging factors of counseling activities. Methodology: The study was conducted using the mix method. The research population included principals, consultants, teachers and students working and studying in the educational system of West Azarbaijan Province during the 2012/2013 educational year. The sample size was 416 respondents comprising of 46 individuals in the qualitative section who were selected based on comments saturation and 370 individuals in the quantitative section selected by use of stratified sampling method. Data were collected by use of researcher‑made interview schedules, and questionnaire then analyzed using Chi‑square, regression, Mann–Whitney, Kruskal–Wallis and Z‑test. Result: The findings indicated the damaging factors of counseling activities and their level of effect were identified. Discussion: Based on the identified levels of effects, the interpersonal factors showed the highest vulnerability toward counseling activities. Therefore, it was recommended that identification and classification of counseling activities’ damaging factors; educational needs assessment by consultants; professional and psychological empowerment of consultants and timing of counseling activities’ implementation may moderate the damaging factors and convert threats into opportunities eventually leading to achievement of the desirable status of counseling activities in schools

The main purpose of this study is to examine the view of school administrators and teachers to school counselor (Psychological Counselor) by metaphor analysis. Comparison method of relational screening models has been followed during the research. Content analysis of qualitative analysis methods has been followed to analyze collected data. Study group of the research had total 390 individuals, 181 of which were school administrators and 209 of which were teachers who worked in the elementary schools in Rize city center and districts in the academic year of 2011-2012. In the form prepared for a data collection tool concerning the research, the participants were asked to complete the sentence “A school counselor (Psychological Counselor) is like ..., because ... “ in order to reveal the perceptions of school counselor (Psychological Counselor) content analysis method and Pearson X2 test was used for the assessment of participants’ statements. When the statements of participants were analyzed, eight total conceptual categories were created from the metaphors they produce. It was shown that school administrators respectively stated the categories in which more metaphors were produced like Guiding, Problem Solving, Developing, Discovering, Friend, Leader, Protector and Ineffective; teachers respectively stated like Guiding, Developing, Problem Solving, Friend, Discovering, Ineffective, Leader and Protector. It was also understood that conceptual categories did not show any significant difference depending on the variables of staff type (school administrator and teacher) and gender. Educational Sciences: Theory & Practice - 13(3) • 1387-1392 ©2013 Educational Consultancy and Research Center

Sovereignty and European Integration, 2001

JOURNAL OF AUSTRALIAN POLITICAL ECONOMY, 2012

Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 2019

Capítulo de Victoria Basualdo y Alejandra Esponda en libro: Archivo Nacional de la Memoria, Los centros clandestinos de detención en la Argentina. Nuevos saberes y miradas a 40 años del Nunca Más , 2023

Revista Brasileira de Otorrinolaringologia, 2004

Universum (Talca), 2019

Przegląd Prawa Rolnego, 2023

Proceedings of the 12th annual international conference on Mobile computing and networking, 2006

Program Studi Komunikasi Penyiaran Islam STID Mohammad Natsir, 2009

Journal of Medicine and Life

European Urology Supplements, 2005

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Sign up for your FREE e-newsletter

You’ll regularly recieve powerful strategies for personal development, tips to improve the growth of your counselling practice, the latest industry news and much more.

We’ll keep your information private and never sell, rent, trade or share it with any other organisation. And you can cancel anytime.

Counselling Case Study: Relationship Problems

Mark is 28 and has been married to Sarah for six years. He works for his uncle and they regularly stay back after work to chat. Sarah has threatened to leave him if he does not spend more time with her, but when they are together, they spend most of the time arguing, so he avoids her even more. He loves her, but is finding it hard to put up with her moods. The last few weeks, he has been getting really stressed out and is having trouble sleeping. He’s made a few mistakes at work and his uncle has warned him to pick up his act.

This study deals with the first two of five sessions. The professional counsellor will be using an integrative approach, incorporating Person Centred and Behavioural Therapy techniques in the first session, moving to a Solution Focused approach in the second session. For ease of writing the Professional Counsellor is abbreviated to “C”.

After leaving school at 17, Mark completed a mechanic apprenticeship at a service station owned by his uncle and has worked there ever since. His father died from a heart attack when Mark was six years old and his uncle, who never married, has been a significant influence in his life. He is the youngest of three children, and the only boy in the family. One sister (Anne) is happily married with two children and the other (Erin) is single and works overseas. Mark and his mother have a close relationship, and he was living at home until his marriage.

Some of Mark’s friends are not married and say he was a fool for ‘getting tied down’ so young. Mark used to think that they were just jealous because Sarah is such a ‘knockout’, but lately he has started to wonder if they were right. In the last couple of months, Sarah has been less concerned about her appearance and Mark has commented on this to her. Sarah had been looking for work, but doesn’t seem to do much of anything now.

Three months ago, Sarah found out she can’t have children. According to Mark, she hadn’t spoken about wanting kids so he guessed it wasn’t a big deal to her. When she told him, Mark had joked that at least they wouldn’t have to go into debt to educate them. He thought humour was the best way to go, because he had never been very good at heavy stuff. Sarah had just looked at him and didn’t respond. He asked if she wanted to go out to a movie that night, and she had started to shout at him that he didn’t care about anyone but himself. At that point, he walked out and went to see his brother-in-law, Joe and sister, Anne.

Since then, he and Sarah hardly spoke and when they did it often turned into an argument that ended with Sarah going into the bedroom, slamming the door and crying. Mark usually walked out and drove over to Joe’s place. When Anne tried to talk to Sarah about it, Sarah got angry and told Anne to keep out of it, after all what would she know about it. She had her kids. Joe and Anne had kept their distance since then. Mark talked to his mother, but she said that this was something he and Anne had to work out together. It was she who suggested that Mark come to see C.

Session One

When Mark arrived for the first session, he seemed agitated. C spent some time developing rapport, and eventually Mark seemed to relax a bit. C described the structure of the counselling session, checked if that was ok with Mark, then asked how C could help him.

Mark: “I really wanted Sarah to come; my wife, but she said that I need to sort myself out. I have to tell you, I don’t think counselling is really for men. Women are the ones that like to talk for hours about their problems. I only came here because she insisted and I don’t want her to walk out on me.”

C: “Your marriage is important to you.”

Mark: “Yeah, sure. We’ve had fights before, but they weren’t anything major. And we always made up pretty quickly. But this is different. It seems like whatever I say is wrong, you know? Lately, I haven’t been able to concentrate properly at work and I wake up a lot through the night. I’m feeling really tired and I wish Sarah would get off my case.”

C used encouragers while Mark described what had been happening over the past few months. When he had finished ventilating his immediate concerns, C, moving into Behavioural techniques, summarized and asked Mark to decide what issue he wanted to deal with first. “Mark, you have discussed a number of issues: you are concerned that communication between you and Sarah has been reduced to mostly arguments; you’re unsure how to deal with the fact that Sarah cannot have children; you want to improve your relationship with Sarah; you are worried that Sarah might leave you, and you are feeling very stressed out. What area would you like to work on first?”

Mark: “I just want her to talk to me without arguing. All this is making it really hard for me to concentrate at work, you know.”

C: “Sounds like two goals there, to reduce your stress and to improve communication between Sarah and yourself.”

M: “Yeah, I guess so. If she would just talk to me instead of crying.”

C used open questions and reflections to encourage Mark to look at his feelings. “How do you feel when she goes into the bedroom and starts crying?” Mark: “Well, she’s never been a crier, and I don’t know what to say to her. If I mention not having children, she will probably cry even more.”

C: “So you feel confused about what to do, and anxious that you may upset her even more.”

Mark: “Yes, I just can’t seem to think straight sometimes. Like, I want things to be the way they were, but it’s just getting worse.”

C informed Mark about the use of relaxation techniques to reduce his stress and checked out if he would like to give it a try. “Mark, you appear to be having difficulty coping because you are feeling very stressed. I believe that learning relaxation techniques would decrease the level of stress and help you think more clearly. How does this sound to you?”

Mark: “I’m not into that chanting stuff if that’s what you mean.”

C explained that there are many forms of relaxation and described the deep breathing and muscle tensing method; Mark agreed to do this for 10 minutes twice a day.

As the first session drew to a close, C reviewed the relaxation technique and asked Mark to practise it as often as possible. A second appointment was arranged for the following week.

At the next session, C asked Mark how the relaxation exercise had helped. “I forget to do it some mornings, so I did it for twenty minutes at night instead. I told Sarah what I’m doing and she just leaves me to it. Not sure if it’s making any difference but I’ll keep doing it. It’s nice to have twenty minutes of peace and quiet.” At this point, C moved into a Solution Focused approach.

C congratulated Mark on commencing the relaxation practice, then checked out if it was okay to ask him some different types of questions. Mark agreed and C asked a miracle question. “Imagine that you wake up tomorrow and a miracle has happened. Your problem has been solved. What would other people notice about you that would indicate things are different?”

Mark looked at C, who waited in silence. Eventually Mark responded. “Ok, they would see me and Sarah talking a lot more, without arguing.”

C: “What else would they notice about you?”

Mark: “I would probably be spending more time at home. You know, not staying back so late at work.”

C: “What would they notice that was different about Sarah?”

Mark: “That’s easy. She wouldn’t be crying and yelling all the time.”

C: “So what would she be doing instead?”

Mark: “I guess she would be talking to me, and smiling.”

After spending some time exploring what would be different if the miracle happened, C asked Mark what he had tried in the past to improve communication. Mark revealed that he bought Sarah some flowers and a box of chocolates (his uncle’s suggestion) but it hadn’t really made any difference. C complimented Mark on his efforts and continued with an exception question.

“Can you think of a recent occasion, when you would have expected a quarrel to start and it didn’t?”

Mark furrowed his brow and appeared to be thinking deeply for some time. C waited in silence. Finally, Mark answered. “Actually, about a week ago, I was a bit late home from work and I was expecting another tongue-lashing, but it never came.”

C asked Mark what was different about that night.

Mark: “Well, Sarah was happier.”

C: “How did you know she was happier?”

Mark: “She talked to me, you know, just talked about something she had seen on the telly or something like that.”

C: “And how was that for you, Mark?”

Mark: “Not bad. Actually, it wasn’t too shabby. We did get to chat, and we haven’t done that for ages.”

C: “Can you explain, “Wasn’t too shabby”; I haven’t heard that term before?”

Mark: “Oh, it means it was all good, you know, it was okay.”

C: “So you came home and chatted with Sarah over a cuppa and you found that wasn’t too shabby?” Both smiled

Mark: “I really liked it. I remember thinking I would have come home earlier if I had known it was going to be like that.”

C: “If I was to ask Sarah what was different about that night, what do you think she would say?”

Mark: “Boy, this is getting weird.”

Mark: “Let’s see. She would probably say, “He actually sat and had a cup of coffee with me, instead of just flopping in front of the telly. She’s always griping about that.”

At the appropriate time, C called for a break. “I’d like to take a break and give us both time to consider all the things we’ve talked about. After that, I will give you some feedback.” After the break C summarized what had been discussed and complimented Mark on the work he had put into exploring his problems. He seemed less stressed and had shown that he was committed to improving his relationship with Sarah.

Counselling continued for another three sessions, by which time Mark’s stress had reduced considerably, he was coming home from work earlier and making an effort to talk more to Sarah. The arguments were less frequent and not so heated.

Session Summary

The Person Centred approach allows the client to take the lead and discuss issues as they see them. This encourages the client to talk openly, which was especially useful in this instance since the client showed a reluctance to do so at first.

The Behavioural technique of goal setting is used to clarify what the client wants to achieve out of the sessions.

Solution Focused Therapy, this approach acknowledges that the client has the ability to solve his own problem.