An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it's official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Browse Titles

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

NICE Medicines and Prescribing Centre (UK). Medicines Optimisation: The Safe and Effective Use of Medicines to Enable the Best Possible Outcomes. Manchester: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE); 2015 Mar. (NICE Guideline, No. 5.)

Medicines Optimisation: The Safe and Effective Use of Medicines to Enable the Best Possible Outcomes.

8 medication review, 8.1. introduction.

Medication review, as an overarching term, has been considered to be an important intervention for many years. Medication review can have several different meanings. It could be a review of medicines carried out every day when a prescriber sees a patient and there is a decision to prescribe or stop a medicine, or a multidisciplinary medication review, with the patient (and their family members or carers where appropriate) present, using a comprehensive and structured approach supported by the patient's full medical records. Medication reviews are carried out in people of all ages.

In 2001, the National Service Framework for older people included a milestone stating that ‘all people over 75 years should normally have their medicines reviewed at least annually and those taking 4 or more medicines should have a review 6 monthly’. The National Service Framework (NSF) did not provide information as to what this medication review should entail or how it should be carried out. To support the implementation of this milestone, it was incorporated into the General Medical Services Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF) from 2006 until 2013.

Room for review – a guide to medication review: the agenda for patients, practitioners and managers was published by the Taskforce on Medicines Partnership, The National Collaborative Medicines Management Services programme in 2002. This document suggested key principles for the process of medication review:

- All patients should have a chance to raise questions and highlight problems about their medicines.

- Medication review seeks to improve or optimise impact of treatment for an individual patient.

- The review is undertaken in a systematic way, by a competent person.

- Any changes resulting from the review are agreed with the patient.

- The review is documented in the patient's notes.

- The impact of any change is monitored.

This document, along with a subsequent National Prescribing Centre document A guide to medication review (2008), aimed to clarify the different types of medication review. Box 1 summarises the different types of medication review, adapted from Room for Review (2002) and A guide to medication review (2008).

Different types of medication review.

In 2005, the National Service Framework for long-term conditions recommended in its quality requirement 1, that ‘people have timely, regular medication review’. Again, there were no specific details about what this medication review entailed.

The National Prescribing Centre issued A guide to medication review (2008), which gave further guidance for medication reviews to commissioners and providers of services. This document further emphasised the need to involve patients in discussions about their medicines and stated that patients ‘had a varied experience of the review and varied perceptions of its benefits’.

In 2013, the GMC issued updated guidance for Good practice in prescribing and managing medicines and devices . The updated guidance provides more detailed advice on how to comply with the principles outlined in the GMC document Good medical practice (2013). The guidance considers the process of reviewing medicines, and suggests that reviewing medicines is particularly important for patients who may be at risk, who are frail or who have multiple illnesses (which may increase polypharmacy ). It is also important for those patients who are taking medicines with potentially serious or common side effects (including high-risk medicines ) or those taking controlled drugs or other medicines that may be abused or misused. Reviewing medicines that require regular monitoring or blood tests is also important. The guidance also considers the role that pharmacists can play in medication review to ‘help improve safety, efficacy and adherence in medicines use, for example by advising patients about their medicines and carrying out medicines reviews’.

Over the years the process of medication review has evolved, but it is not a new approach. It can be carried out in a wide range of settings and the type and depth of medication review carried out varies. The type of health professionals who carry out medication reviews has also changed, with the changing medical model of prescribing, supplying and administering medicines (see section on medicines-related models of care). Regardless of which health professional is carrying out the medication review, there appears to be variation in how and when reviews are carried out.

Furthermore it is important to consider the cost of medication reviews to the NHS. Cost effectiveness analyses of medication review have been carried out over a number of years, often alongside RCTs or other clinical studies. Costing studies for medication reviews have been carried out in several different countries. Such analyses calculate the costs of performing medication reviews and some aim to determine the subsequent costs and health benefits of the intervention.

Medicines use reviews are different from medication reviews because the pharmacist carrying out the review does not have access to the patient's medical records. A medicines use review can complement a medication review. Information about medicines use reviews is available on the Royal Pharmaceutical Society website . In addition to medicines use reviews, community pharmacists also provide a new medicines service to support people with long-term conditions who are newly prescribed a medicine to improve adherence. Several other NICE guidelines recommend carrying out a medication review. Again in many of the guidelines details about how the medication review should be carried out, who should be involved and the overall process are not specified.

For the purpose of this guideline, when the term medication review is used, this is ‘a structured, critical examination of a person's medicines with the objective of reaching an agreement with the person about treatment, optimising the impact of medicines, minimising the number of medication-related problems and reducing waste’ ( National Prescribing Centre 2008 ).

Medication reviews can be offered at different levels, by different health professionals working in different settings. Therefore the aim of this review question was to review whether the evidence for a full, structured medication review led to a reduction in suboptimal use of medicines and medicines-related safety incidents.

8.2. Review question

What is the effectiveness and cost effectiveness of medication reviews to reduce suboptimal use of medicines and medicines-related patient safety incidents, compared to usual care?

8.3. Evidence review

A systematic literature search was conducted (see appendix C.1 ), which identified 1565 references. The review protocols identified the same parameters for the review question on medication review and medicines reconciliation. Therefore a single search was carried out. After removing duplicates, the references were screened on their titles and abstracts and each included study was identified as being relevant for inclusion for the review question on medicines reconciliation or medication review. Sixty-five references were obtained and reviewed against the inclusion and exclusion criteria as described in the review protocol for medication review ( appendix C2.4 ).

Overall, 52 studies were excluded because they did not meet the eligibility criteria. A list of excluded studies and reasons for their exclusion is provided in appendix C5.4 .

Thirteen studies met the eligibility criteria and were included. In addition, 7 systematic reviews of studies ( RCTs and observational) were identified. The references included in these systematic reviews were also screened on their titles and abstracts, to identify any further studies that met the eligibility criteria. Fifteen additional studies were included.

All the included 28 studies were RCTs investigating the effect of medication reviews compared with usual care (see appendix D1.4 evidence tables for details). The studies were carried out in an adult population; there were no studies identified that looked at medication reviews in children. Twelve of the studies targeted medication reviews for patients with long-term conditions such as hypertension, angina, asthma, hyperlipidaemia, diabetes, coronary heart disease, arthritis and osteoporosis. Twenty-one RCTs looked at pharmacist-led medication review, 6 RCTs looked at multidisciplinary team-led medication review and 1 RCT looked at physician-led medication review.

The studies were quality assessed using the NICE methodology checklists for RCTs (see NICE guidelines manual 2012 ). Appraisal of the quality of the study outcomes was carried out using GRADE.

See appendix D1.4 for evidence tables summarising included studies.

See appendix D2.4 for GRADE profiles.

There was some pooling of studies, although this was limited because the outcomes measures used differed and the follow-up periods reported varied between the studies.

Mean differences were calculated for continuous outcomes and odds ratios for binary outcomes, as well as the risk ratios for dichotomous data. When a meta-analysis was possible, a forest plot was presented (see appendix D2.4 ).

Summary of included studies.

8.4. Health economic evidence

Summary of evidence.

A systematic literature search was undertaken ( appendix C.1 ) to identify cost effectiveness studies comparing medication reviews to reduce the suboptimal use of medicines. This search identified 1507 results, of which 1480 records were excluded following screening of their titles and abstracts. The full papers of 27 studies were assessed for relevance against the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Sixteen studies did not meet the inclusion criteria, the reasons for which are listed in appendix C.6.4 . A further 3 studies were identified as relevant from the clinical evidence review, resulting in a total of 14 studies meeting the inclusion criteria.

The studies meeting the inclusion criteria were quality assessed using the NICE quality assessment checklists for cost effectiveness studies. Following this, 4 studies were judged not applicable to the guidance because better quality studies (considering health-related quality of life), more relevant to a UK NHS setting, had been identified. An additional study ( Burns et al. 2000 ) was judged by the GDG to be not relevant to the current UK NHS because of the age of the study. This study was a cost comparison study with a short time horizon and therefore evidence more relevant to the decision problem had already been included. These 5 studies judged not applicable to the guidance were excluded from further analysis. Three further studies were considered to have very serious limitations and were excluded on that basis.

Table 22 shows the economic evidence profile based on the 6 included studies. These studies were judged to be partially relevant to the guidance. The evidence was of variable quality: 4 of the 6 included studies were of low quality and 2 were of high quality. The economic evidence on medication review was limited to review by pharmacists in different settings with no analysis beyond a 12-month time horizon ( appendix E1.4 ).

Economic evidence profile – medication reviews.

A health economic model was not pursued in this area because of the lack of data on medication reviews carried out by health professionals other than pharmacists. There is already an evidence base of published cost–utility studies relating to pharmacist review, so the GDG judged that a de novo model in this area would not help their recommendations. The limited data availability relating to other types of medication review meant that a robust economic model could not be constructed. To aid the GDG discussions a simple costing analysis was undertaken to compare the costs of medication reviews undertaken by a variety of health professionals. A summary of this is provided after table 23 .

Estimate of cost per medication review delivered.

Summary of economic modelling

A summary of the simple cost analysis carried out for this area of the guidance is provided. See appendix F for a full report of the cost analysis carried out for this clinical guideline topic.

Simple costing calculations were carried out to provide the GDG with information around the cost per medication review undertaken dependent upon the health professional delivering the review. These are displayed in table 23 . The length of time utilised for each medicine review was estimated by the GDG and various scenarios are displayed. Health professional costs were sourced from the Personal Social Services Research Unit (PSSRU) ( PSSRU, 2013 ).

A variety of cost options are displayed, which include salary costs only, PSSRU unit cost per health professional and PSSRU unit cost per hour of health professional contact with patients, for consideration by the GDG. It is important to note that an NHS and PSS perspective should be taken for all NICE guidance ( NICE, 2012 ). The costs provided in table 23 are limited in that they provide no information on the quality and impact of the review, nor the long term cost savings resulting from the review.

8.5. Evidence statements

Clinical evidence.

Low-quality evidence from 10 RCTs showed no significant difference in mortality between patients receiving medication review or usual care. The patient populations in the 10 RCTs were people with a mean age of 65 years or over, and who had medication reviews carried out by pharmacists (8 RCTs), a physician (1 RCT) or a clinical pharmacologist (1 RCT).

Low-quality evidence from 2 RCTs pooled together to show the effect of pharmacist-led medication review on targeted hypertensive patients showed that there was a significant change in mean blood systolic pressure in the intervention group compared with control group to meet the target blood pressure.

Low-quality evidence from 1 RCT showed that pharmacist-led medication reviews in a population with a mean age of 65 years significantly increased the percentage of intervention patients achieve target blood pressure compared with usual care. The same RCT showed a significant improvement in low-density lipoprotein (LDL) levels, reaching target INR with anticoagulation and improving diabetes control by meeting HbA 1c targets with medication reviews.

Moderate- and low-quality evidence from 2 RCTs showed that medication reviews compared with usual care in a population with a mean age of 60 years reported no significant differences in the following clinical outcomes (as reported in the studies): proportion of patients prescribed cardiovascular medicines for secondary prevention, 5-year risk of cardiovascular death score, target lipid levels or reduction in LDL levels and changes in cardiovascular risk factors.

Low-quality evidence from 1 RCT showed that medication reviews in patients with asthma significantly improved the optimisation of asthma medicines, asthma severity and inhaler technique, but there was no improvement in spirometry results compared with usual care.

Moderate-quality evidence from 1 RCT showed that medication review significantly reduced the need for rescue medicine and night-time awakenings in patients with asthma. However, it did not improve the peak expiratory flow, asthma control test (ACT) scores or occurrence of severe exacerbations of asthma.

Moderate-quality evidence from a meta-analysis of 2 RCTs showed that medication reviews in a population with a mean age of 84 years significantly reduced the number of falls. One low-quality evidence RCT reported that medication reviews did not significantly reduce the number of fractures in the elderly. Another moderate-quality evidence RCT carried out in a population with a mean age of 68 years showed that medication reviews when compared with usual care significantly improved pain scores, pain severity score, arthritis self-efficacy pain scale scores and clinical response within the first 3 months of the intervention.

Low-quality evidence from 1 RCT showed that medication reviews did not significantly improve the reporting of adverse drug events compared with usual care.

Moderate-quality evidence from 1 RCT showed no significant differences in the number of adverse drug events per 1000 days between the groups that received medication review or usual care.

Moderate-quality evidence from 2 RCTs showed that medication reviews identified more medicines-related problems compared with usual care, but there was no significant difference between the 2 groups. In 1 RCT, medication reviews significantly reduced the mean number of potential medicines-related problems from baseline to endpoint compared with usual care. Another RCT identified medicines-related problems in 71% of patients who received usual care before having a medication review.

Moderate-quality evidence from 1 RCT in an elderly population showed that medication reviews significantly reduced the prescribing of inappropriate medicines compared with usual care.

Moderate-quality evidence from 1 RCT showed that medication reviews in patients with a mean age of 65 years reduced the Medication Appropriateness Index (MAI) scores in all 10 domains compared with usual care. However, the statistical significance of the results was not reported.

Low-quality evidence from 2 RCTs pooled together showed that medication reviews significantly reduced the MAI scores compared with usual care. One moderate-quality evidence RCT showed that medication reviews reduced the number of potentially inappropriate medicines per patient compared with usual care, but this was not significant. Moderate-quality evidence from 1 RCT showed that medication reviews identified more inappropriate medicines (as per Beers criteria) prescribed (although not significant) and also identified significantly more underused medicines (as per ACOVE criteria) compared with usual care.

Moderate-quality evidence from 1 RCT carried out in patients with dyslipidaemia showed that medication reviews reduced the number of patients being prescribed high-intensity statins compared with usual care. Moderate-quality evidence from 2 RCTs and low-quality evidence from 4 RCTs which reported on the mean number of medicines per patient for the study showed that there was no significant difference between the usual care and medication reviews after the follow-up period.

Moderate- and low-quality evidence from 2 RCTs showed that medication reviews significantly reduced the mean number of medicines prescribed compared with usual care. Moderate-quality evidence from 1 RCT reported a significantly smaller increase in the number of medicines prescribed to elderly patients who had medication reviews compared with usual care.

Low-quality evidence from 2 RCTs and moderate-quality evidence from 1 RCT showed that medication reviews significantly increased compliance compared with usual care. Moderate-quality evidence from 3 RCTs showed no significant difference in patient compliance between the groups that received medication reviews or those that received usual care.

Moderate-quality evidence from 2 RCTs and low-quality evidence from 1 RCT showed no significant difference in patient satisfaction between medication review and usual care. Moderate-quality evidence from 2 RCTs showed that medication reviews received significantly high patient satisfaction rates compared with usual care.

Moderate-quality evidence from 1 RCT showed no significant difference in the change in depression and anxiety scores for patients who received medication reviews or usual care. The same study showed that medication reviews significantly improved patients' clinical response to knee pain management (using the OMERACT-OARSI responder criteria) at 3 months compared with usual care. There was no significant difference at the end of the 12-month study.

Economic evidence

Partially applicable evidence from 2 studies with minor limitations, built on RCT data, suggests that pharmacist review is not cost effective, with ICERs above £50,000/QALY, compared with no intervention.

Partially applicable evidence from 4 studies with potentially serious limitations provided conflicting evidence, with 3 studies finding pharmacist review to be cost incurring and 1 finding it to be cost saving compared with no intervention.

No evidence was identified informing cost effectiveness of medication reviews by health professionals other than pharmacists.

8.6. Evidence to recommendations

Linking evidence to recommendations (LETR).

8.7. Recommendations and research recommendations

Medication review can have several different interpretations and there are also different types which vary in their quality and effectiveness. Medication reviews are carried out in people of all ages. In this guideline medication review is defined as ‘a structured, critical examination of a person's medicines with the objective of reaching an agreement with the person about treatment, optimising the impact of medicines, minimising the number of medication-related problems and reducing waste’. See also recommendation 33.

Consider carrying out a structured medication review for some groups of people when a clear purpose for the review has been identified. These groups may include:

- adults, children and young people taking multiple medicines ( polypharmacy )

- adults, children and young people with chronic or long-term conditions

- older people.

Organisations should determine locally the most appropriate health professional to carry out a structured medication review, based on their knowledge and skills, including all of the following:

- technical knowledge of processes for managing medicines

- therapeutic knowledge on medicines use

- effective communication skills.

The medication review may be led, for example, by a pharmacist or by an appropriate health professional who is part of a multidisciplinary team.

During a structured medication review, take into account:

- the person's, and their family members or carers where appropriate, views and understanding about their medicines

- the person's, and their family members' or carers' where appropriate, concerns, questions or problems with the medicines

- all prescribed, over-the-counter and complementary medicines that the person is taking or using, and what these are for

- how safe the medicines are, how well they work for the person, how appropriate they are, and whether their use is in line with national guidance

- whether the person has had or has any risk factors for developing adverse drug reactions (report adverse drug reactions in line with the yellow card scheme )

- any monitoring that is needed.

8.7.1. Research recommendation

To be read in conjunction with the NICE Research recommendations process and methods guide )

Uncertainties

This review question looked at the clinical and cost effectiveness of medication reviews to reduce the suboptimal use of medicines and medicines-related patient safety incidents, compared to usual care or other interventions. The systematic review provided no evidence for medication reviews carried out in children.

Uncertainties may be related to:

- clinical effectiveness and cost effectiveness of medication reviews carried out in children.

Reason for uncertainties

The searches did not identify any randomised controlled trials (RCTs) looking at medication reviews carried out in children. Although RCTs have been carried out in an adult population, the GDG found the outcomes used to measure the effectiveness were mixed. The GDG agreed that, although the principles of medication reviews carried out in adults can be applied to children, further research is needed in children because of the different levels of engagement and because it often needs parent or carer involvement where appropriate when carrying out the medication review. RCTs may not have been carried out in children because of ethical aspects.

The GDG also discussed and agreed that there was uncertainty about the following factors, which may affect the clinical and cost effectiveness of medication reviews:

- the type of medication review carried out (see section 8.1 )

- which health professional is carrying it out

- the frequency of medication review.

The GDG found that the above factors varied between the studies that were carried out in adults.

Key uncertainty

The key uncertainty is whether medication reviews can reduce the suboptimal use of medicines and medicines-related patient safety incidents compared with usual care or other interventions in children.

This uncertainty can be answered by conducting a study that will deliver good quality evidence, such as an RCT.

Recommendation

- Is a medication review more clinically and cost effective at reducing the suboptimal use of medicines and medicines-related patient safety incidents, compared with usual care or other interventions, in children?

The research should be carried out in children that use services where medication reviews can be carried out.

Study methodology can be based on other well-conducted RCTs that have been carried out in adults, the difference being the age of the population. Approval from ethics or other committees would be needed given the young age of the population. ‘Usual care’ or other interventions would be used as a comparator. ‘Usual care’ would need to be defined in the study. A follow-up period of 1–2 years or more would capture longer-term outcomes. The outcomes for this research question should be patient-centred and include suboptimal use of medicines, medicines-related patient safety incidents, patient-reported outcomes, clinical outcomes, medicines-related problems, health and social care resource use and cost effectiveness.

The study would need to take into account:

- the type of medication review carried out (see section 8.1 ); the study needs to outline a framework of the medication review to help guidance developers to see the process used; they would then be better able to decide if it would affect clinical effectiveness of the intervention

- the health professional carrying it out

- child, parent and carer involvement as this may affect some outcome measures, depending on their engagement level

- the frequency of medication review (this would impact on cost effectiveness of resource use).

The GDG recognised that the key focus of the medicines optimisation agenda is to make care person-centred. In line with this and to ensure the best use of NHS resources, the GDG agreed that research needs to be carried out in children to identify the benefit from them having medication reviews. There may be some longer-term gains with this approach, as from a young age the child would become more aware of the intervention, develop a relationship with the health professional and be encouraged to understand their medicines.

Research into this area will provide guidance to organisations who may want to, or already provide, medication reviews as part of their care and enable better use of resources (for example, health professional cost and time and health and social care resources). This information would be useful to commissioners who may consider whether or not to commission providers to carry out medication reviews.

Proposed format of research recommendations.

8.7.2. Research recommendation

To be read in conjunction with the NICE Research recommendations process and methods guide .

This review question looked at the clinical and cost effectiveness of medication reviews to reduce the suboptimal use of medicines and medicines-related patient safety incidents, compared to usual care or other interventions. The GDG found that the systematic review provided no economic evidence for medication reviews carried out by health professionals other than hospital or community pharmacists.

- cost effectiveness of medication reviews carried out in all settings, professional-led or carried out by a multidisciplinary team.

Reason for uncertainty

Most of the clinical and economic evidence identified related to medication reviews carried out by community or hospital pharmacists. There were randomised controlled trials (RCTs) that looked at the clinical effectiveness of medication reviews carried out by a doctor and by multidisciplinary teams (comprising a doctor, pharmacist and/or nurse), but there was no economic evidence for these. Therefore, the GDG was uncertain about the cost effectiveness of professional-led (other than hospital or community pharmacists) and multidisciplinary team medication reviews as no relevant data were available to feed into an economic model.

In addition, the included studies varied in quality and were carried out in Europe, Australia, Canada or the USA. The GDG was aware of the limitations relating to the applicability of some of these studies to the UK setting given the differences in healthcare systems and processes and populations.

The GDG discussed and agreed that the clinical and cost effectiveness of medication reviews would depend on several factors such as:

- type of health professional carrying it out

Although the GDG was presented with a high number of RCTs for this review question, there was uncertainty about the above factors, which varied in the included studies.

Key uncertainties

The economic evidence presented to the GDG on medication review was limited to review by hospital and community pharmacists. The GDG found that the evidence was conflicting and of varying quality. The GDG was uncertain about the cost effectiveness of medication reviews carried out by multidisciplinary teams or professional-led by health professionals other than hospital or community pharmacists, compared to usual care or other interventions. No economic evidence was found for primary care pharmacists carrying out medication reviews. The GDG agreed that there was uncertainty about this and that the research recommendation should include primary care pharmacists.

These uncertainties can be answered by conducting a study that will deliver good-quality evidence, such as an RCT.

Is a medication review more clinically and cost effective at reducing the suboptimal use of medicines and improving patient-reported outcomes, compared with usual care or other intervention in the UK setting?

The study should consider the cost effectiveness of the health professional(s) carrying out the medication review.

The medication review should be carried out by a multidisciplinary team or be professional-led by any health professional other than a community or hospital pharmacist to provide data to develop an economic model for cost effectiveness. There is already economic evidence available for community and hospital pharmacists (see section 8.4 ).

Research can be carried out using an RCT. Study methodology can be based on other well-conducted RCTs that have been carried out looking at medication reviews. ‘Usual care’ or other interventions would be used as a comparator. ‘Usual care’ would need to be defined in the study. A follow-up period of 1–2 years or more would capture longer-term outcomes. Outcomes for this research question should be patient-centred and include the suboptimal use of medicines, patient-reported outcomes, clinical outcomes, medicines-related problems, health and social care resource use and cost effectiveness.

- the type of medication review carried out (see section 8.1 ); the study would need to outline a framework of the medication review to help guidance developers to see the process used; they would then be better able to decide if it would affect clinical effectiveness of the intervention

- type of health professional carrying out the medication review

The GDG recognised that the key focus of the medicines optimisation agenda is to make care person-centred and to have services that support people in the optimal use of their medicines. Medication reviews can be offered to people by different health professionals at different levels, working in different settings. Resources (for example, staff and time) needed to enable routine medication review may vary locally depending on the setting and health professional availability.

Research into this area will provide guidance to organisations who may want to, or already provide, medication reviews as part of their care and enable better use of resources (for example, health professional cost and time and health and social care resources) and facilitate service delivery. This information would be useful to commissioners who may consider whether or not to commission medication reviews by providers.

All rights reserved. This material may be freely reproduced for educational and not-for-profit purposes. No reproduction by or for commercial organisations, or for commercial purposes, is allowed without the express written permission of NICE.

- Cite this Page NICE Medicines and Prescribing Centre (UK). Medicines Optimisation: The Safe and Effective Use of Medicines to Enable the Best Possible Outcomes. Manchester: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE); 2015 Mar. (NICE Guideline, No. 5.) 8, Medication review.

- PDF version of this title (3.8M)

In this Page

- Introduction

- Review question

- Evidence review

- Health economic evidence

- Evidence statements

- Evidence to recommendations

- Recommendations and research recommendations

Other titles in this collection

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence: Guidelines

Recent Activity

- Medication review - Medicines Optimisation Medication review - Medicines Optimisation

Your browsing activity is empty.

Activity recording is turned off.

Turn recording back on

Connect with NLM

National Library of Medicine 8600 Rockville Pike Bethesda, MD 20894

Web Policies FOIA HHS Vulnerability Disclosure

Help Accessibility Careers

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Interventions to optimize medication use in nursing homes: a narrative review

Anne spinewine, perrine evrard, carmel hughes.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Corresponding author.

Received 2020 Oct 20; Accepted 2021 Feb 25; Issue date 2021.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Key summary points

This review aimed to identify, describe and discuss different interventions targeting medication use optimization in nursing homes and to identify research gaps.

Prescription of the whole medication regimen or of specific medication classes was the most studied aspect. Medication review and multidisciplinary approaches appeared to be effective strategies in reducing appropriate use, but further large-scale randomized trials are needed.

Efforts to optimize medication use among nursing home residents are still needed and should focus on less evaluated intervention components, specific medication classes and medication use aspects not related to prescribing.

Keywords: Nursing homes, Older adults, Medication optimization, Potentially inappropriate prescriptions, Interventions, Implementation

Polypharmacy, medication errors and adverse drug events are frequent among nursing home residents. Errors can occur at any step of the medication use process. We aimed to review interventions aiming at optimization of any step of medication use in nursing homes.

We narratively reviewed quantitative as well as qualitative studies, observational and experimental studies that described interventions, their effects as well as barriers and enablers to implementation. We prioritized recent studies with relevant findings for the European setting.

Many interventions led to improvements in medication use. However, because of outcome heterogeneity, comparison between interventions was difficult. Prescribing was the most studied aspect of medication use. At the micro-level, medication review, multidisciplinary work, and more recently, patient-centered care components dominated. At the macro-level, guidelines and legislation, mainly for specific medication classes (e.g., antipsychotics) were employed. Utilization of technology also helped improve medication administration. Several barriers and enablers were reported, at individual, organizational, and system levels.

Overall, existing interventions are effective in optimizing medication use. However there is a need for further European well-designed and large-scale evaluations of under-researched intervention components (e.g., health information technology, patient-centered approaches), specific medication classes (e.g., antithrombotic agents), and interventions targeting medication use aspects other than prescribing (e.g., monitoring). Further development and uptake of core outcome sets is required. Finally, qualitative studies on barriers and enablers for intervention implementation would enable theory-driven intervention design.

Introduction

Medication use among nursing home residents (NHRs) is very common. Indeed, in nursing homes (NHs), polypharmacy is highly prevalent, with 91%, 74% and 65% of NHRs taking more than five, nine and 10 medications, respectively [ 1 ]. These rates of polypharmacy are higher than what has been reported in home-dwelling older adults (27.0–59.0% taking 5 or more medications [ 1 ]). Factors associated with polypharmacy among NHRs include age, cognitive status, number of prescribers, dependency and length of stay in the NH [ 1 ].

Polypharmacy, together with other factors such as altered pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics, and complexity of the medication use process, makes the safe use of medications for NHRs highly challenging [ 2 ]. Reported rates of adverse drug events (ADEs) in NHs range from 1.89 to 10.8 per 100 resident-months [ 3 ]. Medication errors (MEs) are common, involving 16–27% of NHRs in studies evaluating all types of MEs and 13–31% of NHRs in studies evaluating MEs occurring at transfer from and to other settings of care [ 4 ]. MEs can occur at any step of the medication use process. These steps include: prescribing, purchase and ordering, delivery, storage, preparation and administration, monitoring and medication reconciliation at transfer [ 5 ]. The minimum practices that are required to deliver high-quality care at each step have been identified and constitute opportunities for evaluation of performance [ 5 ]. The literature suggests that the majority of errors occur at the prescribing, monitoring, administration, and medication reconciliation steps [ 4 ]. In a recent review, five categories of factors related to the work system were found to affect medication safety in NHs: persons (resident and staff, e.g., number of medications, staff medication knowledge), organization (e.g., inter-professional collaboration, staff/resident ratio), tools and technology (e.g., bar-code medication system), tasks (e.g., workload and time pressure), and environment (e.g., staff interruption) [ 3 ]. It is expected that interventions to optimize medication use in NHs would address these steps and factors as priorities.

The prescribing component is an important aspect of medication optimization, as prevalence of potentially inappropriate prescriptions (PIPs) is high, and as PIP and polypharmacy have been associated with adverse outcomes such as lower quality of life, hospitalizations, falls, and frailty [ 1 , 6 – 8 ]. PIPs encompass underprescribing (failure to prescribe a needed drug), overprescribing (prescribing more drugs than needed) and misprescribing (incorrect prescribing of a needed drug) [ 2 ]. The estimated prevalence of PIPs among NHRs is 43.2% [ 9 ]. This prevalence tends to rise over time and the situation is more concerning in Europe, with higher reported point prevalence (49.0%) than these reported in North America (26.8%) or other countries (29.8%) [ 9 ]. Several factors were found to be associated with PIPs such as total number of medications taken, age, location of the NH (including country, urban versus rural), dementia and comorbidity burden [ 9 , 10 ]. The most commonly reported inappropriate medications include psychotropic drugs, medications with anticholinergic properties, antimicrobials, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and proton-pump inhibitors [ 9 , 11 , 12 ].

Interventions to optimize medication use can be implemented at different levels of the health care system. Throughout the literature there is inconsistency in the number and definitions of these levels [ 13 ]. For this review, we distinguish between two levels. First, the micro-level refers to interventions implemented at the NH level and directed at NHRs, health care providers (HCPs) and organization of the NH itself. Second, the macro-level (also called system-level) encompasses strategies that are external to NHs but impact on their practice. These are typically but not exclusively defined at a national or regional level.

The main objective of this review is to identify, describe and discuss interventions aimed at optimization of any step of medication use in NH, in terms of content, effects, as well as barriers and enablers to their implementation. As a second objective, we aimed to identify perspectives for the future at the research and practice levels.

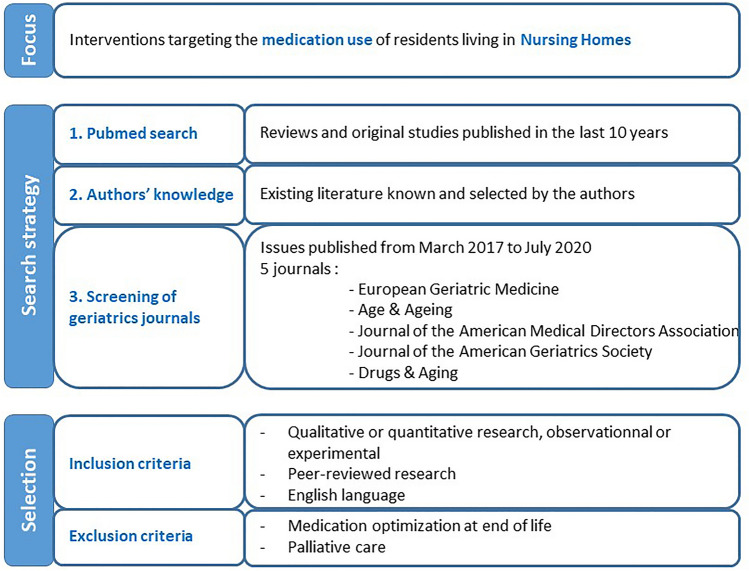

This review was conducted using a narrative process. We focused on interventions targeting the medication use of residents living in NHs. Relevant references were identified and selected from a search in PubMed, the authors’ existing knowledge of literature, and recent publications in geriatrics journals. Finally, we retrieved additional studies by hand-searching reference lists of identified articles. Searching additional databases (e.g., Embase, CINAHL) would have been valuable and relevant in the context of a systematic review, but this was beyond the scope of the present work.

We selected quantitative as well as qualitative studies, observational and experimental studies that described interventions, their effect as well as barriers and enablers. We only included peer-reviewed research published in English. Given the large volume of literature, we prioritized results from the most recent (systematic) reviews and original studies published after these reviews were completed. We did not restrict the country where research took place, but gave preference to studies conducted in Europe or with relevant data or messages for European settings, as judged by the research team. We did not include papers focusing on medication optimization at end of life or during palliative care which was considered beyond the scope of this review. The search strategy and papers’ selection process are presented in Fig. 1 .

Search strategy and papers’ selection process

Because an important part of the literature focuses on the prescribing component, we first review this aspect, followed by approaches to improve other aspects of medication use. In the section on prescribing, we review separately the approaches concerned with optimizing the whole medication regimen and those concentrating on specific drugs or classes, because the approaches, their effect, as well as barriers and enablers may differ, and hence, merit separate consideration.

Interventions to optimize prescribing for the whole medication regimen

Three recent systematic reviews (SRs) evaluated the effect of micro-level interventions—largely based on medication review (MR)—to optimize prescribing in the NH setting and reported positive results on quality of prescribing [ 14 – 16 ]. A Cochrane SR highlighted four different approaches for optimization: MR, multidisciplinary case-conferencing, education for HCPs, and use of clinical decision support system (CDSS) [ 14 ]. These were used either alone, or in combination. Overall, the interventions led to identification and resolution of drug-related problems, but there was no consistent effect on resident-related outcomes [ 14 ]. In a second SR focusing on MR and including experimental and observational study designs, interventions were associated with a reduction in prescribed medications, inappropriate medications and adverse outcomes (including deaths and hospitalizations) [ 15 ]. However, high-quality cluster-randomized controlled trials evaluating CDSS effects or evaluating the impact of multidisciplinary interventions on well-defined important resident-related outcomes were lacking [ 14 , 15 ]. In terms of deprescribing, a SR of specific interventions reported a reduction of 59% of NHRs receiving at least one PIP [ 16 ]. Only interventions including a MR were associated with a reduction in all-cause mortality and number of fallers [ 16 ].

Five trials performed in European Union (EU) countries NHs were published after these SRs and are summarized in Table 1 [ 11 , 17 – 20 ]. These were all multicenter studies—three were cluster-randomized controlled trials—and involved multidisciplinary interventions mainly consisting of education of HCPs and MR. None involved a CDSS component. Participation of NHR was one component of the intervention in two studies. The study by Wouters et al. involved NHRs through a questionnaire on their preferences and experiences as a step of MR [ 18 ]. In the COSMOS study, NHRs were asked about their interest in participating in different activities [ 20 ]. Overall, results from these five trials were consistent with those of previous SRs, with positive effects on polypharmacy and PIPs—although the measures used to define PIPs varied widely across studies, and none of the tools used were specific to the NH setting. Clinical and humanistic outcomes were inconsistently evaluated (Table 2 ). Two trials reported no effect of the intervention on clinical outcomes and/or quality of life [ 11 , 18 ]. In the COSMOS study, an initial decline in quality-of-life was found in the intervention group—initial NHR unhappiness with the MR is one of the possible explanations raised by the authors—but this decrease reversed significantly during follow-up [ 20 ].

Trials conducted in European nursing homes in the last 5 years and reporting the effect of an intervention on prescribing the whole medication regimen (chronological order)

ADL activities of daily living, ARR adjusted relative risk, BAS before–after study, CG control group, CGIC clinical global impressions of change, CI confidence interval, CT controlled trial, DRP drug-related problems, GP general practitioner, IG intervention group, MR medication review, mo months, N nurse, NH nursing home, NHR nursing home resident, OR odds ratio, PIP potentially inappropriate prescription, QoL quality of life, RCT randomized controlled trial, cRCT cluster-RCT, START/STOPP screening tool to alert doctors to right treatment/screening tool of older persons’ prescriptions

Outcomes and process measures reported in trials conducted in European nursing homes in the last 5 years

ADL activities of daily living, AGS American Geriatrics Society, APID appropriate psychotropic drug use in dementia index, CGIC Clinical Global Impression of Change, DBI Drug Burden Index, DQI dementia quality of life instrument, ED emergency department, EQ-5D-3L EQ-VAS European quality of life visual analog scale, HCPs health care providers, QoL-AD quality of life in Alzheimer’s disease scale, QUALID quality of life late-stage dementia scale, QUALIDEM quality of life dementia scale, MMSE mini-mental state examination, PIP potentially inappropriate prescription, SIB-S severe impairment battery-short, START/STOPP screening tool to alert doctors to right treatment/screening tool of older persons’ prescriptions. ‘X’ without further detail means that the outcome was reported, but no details on measurement were given.

Beyond the evaluation of the effect of interventions, a clear understanding of the enablers and barriers to implementation and success is crucial for the development of future interventions. It is encouraging to see that three of the trials presented in Table 1 addressed this question, mainly through questionnaires and interviews of HCPs [ 21 – 23 ]. Wouters et al. also interviewed NHRs [ 21 ]. Overall, the interdisciplinary approaches were recognized as key elements for the success of interventions, despite organizational and time constraints. The attitude, role and competency of HCPs (physicians, pharmacists and nurses) were identified both as barriers and enablers. The need for funding MRs at the macro-level was also reported. Assessing the patient perspective was reported to be a delicate balance between the value and the barriers to a proper assessment of the patient perspective. Other qualitative studies assessed the specific barriers and enablers of deprescribing in the NH setting [ 24 , 25 ]. While many were similar to what was reported for intervention implementation, HCPs’ concerns about deprescribing and perceived reluctance of NHRs to change were more specific to deprescribing interventions. This highlights the need for deprescribing guidance and shared decision-making [ 24 , 25 ].

Interventions to optimize prescribing for specific drug classes

In the section below, we focus on three medication classes for which inappropriate use is highly prevalent and is a threat to patient safety. For each of these, we first briefly describe data on their (inappropriate) use, then review the evidence on approaches for optimization, as well as barriers and enablers for improvement. Table 3 describes five recent studies conducted in NHs in Europe, four on psychotropic drugs and one on anti-infective drugs. We found no recent EU study focusing on DAP.

Trials conducted in European nursing homes in the last 5 years and reporting the effect of an intervention on prescribing a specific medication class (chronological order)

APID appropriate psychotropic drug use in dementia, ARR adjusted relative risk, BAS before–after study, CG control group, CGIC clinical global impressions of change, CI confidence interval, CT controlled trial, DDD defined daily dose, DRP drug-related problems, GP general practitioner, IG intervention group, MR medication review, mo months, N nurse, NH nursing Home, NHR nursing home resident, OR odds ratio, P pharmacist, PIP potentially inappropriate prescription, PSM propensity score-matched, QoL quality of life, RCT randomized controlled trial, cRCT cluster-RCT, START/STOPP screening tool to alert doctors to right treatment/screening tool of older persons’ prescriptions

Psychotropic drugs

Psychotropic drugs are used extensively in NHs, with wide variation in rates of prescribing between countries. In NHs in Western European countries, antipsychotic use ranges from 12 to 59% of NHRs and antidepressant use is even higher, from 19 to 68% [ 31 ]. The use of benzodiazepine receptor agonists (BZRA, namely benzodiazepines and Z-drugs) ranges from 14.6% (Canada, [ 32 ]) to 54.4% (France, [ 33 ]). Concomitant use of several psychotropic drugs is also high with 31.5% of NHRs taking two or more such medications [ 29 ].

Beyond this high prevalence of use, frequent inappropriate use is a concern. Indeed, psychotropic drugs are often the most commonly reported inappropriate medications among NHRs [ 9 , 11 , 34 ]. The inappropriate (and off-label) use of antipsychotics for behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia has received the most attention. This has led to national and international calls and programs for deprescribing of antipsychotics in NHs. Even though the appropriateness of antidepressants and BZRA use has been less widely studied, recent data suggest that these medicines should also give rise to concern. In a study with 2651 French NHRs receiving an antidepressant, PIP (with regard to indication, drug class, duplication and monitoring) was found in 38.4% of NHRs [ 35 ]. In a Belgian study with 418 NHRs taking a BZRA, 98% of NHRs received the BZRA for more than 4 weeks, and drug–disease and drug–drug interactions were found in two-thirds of users overall [ 36 ]. In both studies, dementia was associated with less PIP.

Data on the factors associated with (inappropriate) psychotropic drug use suggest that approaches for improvement can be considered both at the macro- and micro-levels. A recent SR found that organizational capacity, individual professional capacity, attitudes, communication and collaboration and regulation or guidelines influenced antipsychotic prescribing [ 37 ]. Similarly, factors associated with psychotropic drugs use included: staffing level or education, teamwork and communication between both on-site and visiting staff, and managerial expectations [ 13 ].

At the macro-level, a recent scoping review including 36 studies (of which only three were performed in Europe) found that mandatory strategies such as legislation (e.g., change in reimbursement, initiation of public reporting of antipsychotic use) had greater evidence of impact on drug utilization than non-mandatory macro-level strategies such as guidelines and recommendations [ 13 ]. The OBRA-87 legislation in the US led to the greatest reduction in psychotropic drug use. However, inappropriate use remains a significant issue and few studies have examined both sustainability of system-level strategies and cost-related outcomes [ 13 ].

At the micro-level, a recent narrative review of approaches for deprescribing psychotropic medications in NHRs with dementia reported that interventions should have more than one component, include multidisciplinary teams and HCPs’ training, and be person-centered [ 38 ]. The same intervention components were highlighted in a SR of factors influencing antipsychotic use among dementia NHRs [ 37 ] and in a review of interventions targeting BZRA deprescribing [ 39 ]. In Europe, a few interventions were recently evaluated, with encouraging results (Table 3 [ 26 – 29 ]). Similar to approaches targeting the whole medication regimen, training of HCPs and MR were important components of evaluated strategies. However, some more specific strategies were also tested. Patient-centered interventions were implemented in three studies. In Belgium, a quality improvement study with transition to person-centered care (e.g., through the implementation of meaningful activities for NHRs) showed a reduction in both long-term use and concomitant use of psychotropics [ 29 ]. In a Spanish study with NHRs with dementia, application of STOPP/START criteria and use of decision aids for NHRs had positive and similar effects on reducing daily dosages of psychotropic drugs, even though decision aids were less often used than STOPP/START [ 28 ]. Richter et al. investigated a person-centered care approach, which had been successfully evaluated in NHs in the UK, and adapted it to the German context. However, the program did not lead to a reduction in antipsychotic prescriptions. Reasons for differences between the UK and Germany were unclear, but the culture of care as reflected in the attitudes and beliefs of nursing staff and a lack of cooperation with physicians may have accounted for the findings [ 27 ].

Drugs with anticholinergic properties (DAP)

DAPs are associated with a wide range of peripheral and central adverse effects (e.g., delirium, fall, urinary retention), and there have been numerous calls to reduce their use [ 40 ]. A recent population-based study among NHRs with depression even found that clinically significant anticholinergic use was associated with a 31% increase in risk of death [ 41 ]. Despite such concerns, DAP are highly prevalent among NHRs. In a study conducted in Helsinki, in 2011, 85% of NHRs were taking at least one DAP [ 42 ]. Positive findings were reported in a study evaluating temporal trends from 2003 to 2017 (the anticholinergic burden decreased, and participants with dementia had a lower anticholinergic burden), but DAP use—especially antipsychotics and antidepressants—remained high [ 43 ]. This calls for action toward DAP use in NH.

A SR reported that (micro-level) interventions aiming at reducing anticholinergic burden in older adults (≥ 65) in different settings often reduced anticholinergic burden [ 40 ]. Pharmacists delivered the intervention in the majority of studies, and authors concluded that these HCPs may be well placed to implement a DAP reduction intervention [ 40 ]. Among the eight studies included, only one was conducted in NHs, in Norway. The intervention consisted of a pharmacist-initiated reduction of anticholinergic drug scale score after multidisciplinary MR. Anticholinergic drug scale scores were significantly reduced in the intervention group and remained unchanged in the control group. However, no improvement in NHRs’ cognitive function at 8 weeks was observed [ 44 ]. In another recent study conducted in New Zealand NHs, pharmacists performed deprescribing recommendations for both anticholinergic and sedative drugs. This showed that deprescribing was feasible, with 72% of recommendations implemented by physicians, without deterioration in quality of life, and with an improvement in depression and frailty scores [ 45 ]. No macro-level approaches specifically targeting DAP use were found.

These data are encouraging but remain very limited, which calls for further well-conducted, large-scale, controlled studies. The variety and heterogeneity of tools to measure and quantify anticholinergic burden remains an issue, as there is no consensus as to which of the tools is most useful in research or clinical settings [ 42 ].

Anti-infective drugs

Antimicrobials are commonly prescribed in NHs and their use is associated with antimicrobial resistance and Clostridium difficile infections. The 2016–2017 point prevalence survey performed in NHs in 24 EU countries found a crude prevalence of NHRs receiving at least one antimicrobial agent of 4.9%, with large variations across and between countries (from 0.7% in Lithuania to 10.5% in Spain and Denmark) [ 46 ]. Prophylaxis for urinary-tract infection was a frequent—and potentially inappropriate [ 47 ]—indication for antimicrobial use (representing almost one third of prescriptions) and did not significantly decline following previous surveys [ 46 ]. Inappropriate prophylactic use of antimicrobials was therefore recommended as a specific target for future interventions. Appropriate prescribing of antimicrobials in NH is challenging and influenced by several factors, such as variations in knowledge and practice among HCPs, social factors, antimicrobial resistance and the specific context of NH care (including restricted access to doctors and diagnostic tests) [ 12 ].

Antibiotic stewardship programs (ASPs) are coordinated interventions promoting the appropriate use of antibiotics to improve patients’ outcomes and reduce microbial resistance [ 48 ], which can be implemented at both the macro- and micro-levels. At the macro-level, ASPs have been mandated in American NHs since November 2017. In Europe, data on ASP indicate that there has been no increase in ASP implementation over time, and improvements in antimicrobial stewardship are urgently needed in EU NHs [ 46 ].

Recent SRs on ASP in the NH setting reported that the most commonly implemented strategies were educational materials, educational meetings, and guideline implementation, combined in multifaceted interventions [ 49 ]. Results suggested an effect on intermediate health outcomes, such as antibiotic consumption or adherence to antibiotic guidelines. However, an effect on key health outcomes such as mortality rates, hospitalizations, or Clostridium difficile infection rates was not demonstrated [ 48 – 50 ]. Moreover, the specific benefit of intervention components is unclear. In Switzerland, ASP activities including local multidisciplinary networks (micro-level strategy) and guidelines publication (macro-level strategy) led to a 22% reduction in antibacterial use over a 6-year period (Table 2 ) [ 30 ]. A recent paper described the ASP implementation experience in four European countries (Norway, The Netherlands, Poland and Sweden) where various regional or national ASP initiatives have recently been introduced [ 51 ]. The ASP components included national surveillance systems, NH-specific prescribing guidelines and national networks of healthcare institutions. No data were provided to document the effect of these initiatives on antimicrobials consumption. Future ASP implementation will need to account of enablers (e.g., the presence of study leaders, skills training for doctors and nurses, and good inter-professional communication) and barriers (e.g., pressures from residents and families, NH staff’s knowledge and belief) in order to be successful, in addition to outcome data [ 12 , 52 ].

Interventions to optimize medication reconciliation at transfer

The transition of NHRs from one setting to another increases the risk for MEs. Indeed, preventable ADEs at transition points account for 46–56% of all MEs [ 53 ] and MEs have been identified as a major source of morbidity and mortality in transitional care [ 54 ]. A possible explanation is poor communication between settings, potentially leading to prescribing errors. When questioned on ways to improve quality and safety of care transfer, NH and emergency department staff raised several strategies, including the use of a standardized transfer form, a checklist and verbal communication between settings [ 55 ].

In practice, some of these interventions have been studied at micro-level. Results from a SR on interventions to improve transitional care between NH and hospitals show that the development of a standardized unique transfer document may assist with the communication of medication lists, and that pharmacist-led review of medication lists may help identify omitted or indicated medications on transfer [ 54 ]. This is supported by results from another SR evaluating medication reconciliation interventions during NHRs’ transfer from and to the NH [ 53 ]. In most studies, a clinical pharmacist performing MR was part of the intervention. All interventions led to outcome improvement, but no study showed strong evidence in reducing medication discrepancies [ 53 ].

Existing data also suggest that HCPs believe that initiatives should be taken at the macro-level, to standardize processes during transitions. National guidance and toolkits relative to medication reconciliation in the NH setting exist in some countries such as Canada [ 56 ], but to the best of our knowledge, the impact of these initiatives on quality and safety of medication use in NHs has not been evaluated.

Interventions to optimize the preparation and administration

The preparation and administration of prescribed drugs often falls to nurses (and sometimes pharmacists for the preparation stage)—and not to NHRs themselves. Medication administration errors (MAEs) encompass different types of errors such as wrong-time errors, wrong-dose errors, omitted doses, wrong-patient errors. As an example, 27% of calls to the Quebec Poison Center for patients aged over 65 resulted from drug administration to the wrong NHR [ 57 ]. The medication administration process is prone to interruptions, and this may increase the risk of MAE. It has been reported that nurses are interrupted at a rate ranging from 0.4 to 14 times an hour [ 58 ]. Swallowing difficulties may also trigger MAEs. Indeed, it is common for nurses to modify medication dosage forms through crushing tablets or opening capsules, in order to administer a medication to NHRs with swallowing difficulties [ 59 ]. Nurses reported that this practice is challenging and would need appropriate guidelines and training [ 59 ].

To reduce the risk of MAEs and resulting harms, different approaches have been taken, and the main focus has been the implementation of technological solutions, such as electronic medication administration record (eMAR) and bar-code medication administration [ 58 , 60 – 62 ]. These technologies might be time-saving, decrease the probability of MAEs such as omitted doses and increase nurse satisfaction [ 61 , 62 ]. However, a SR on eMAR in long-term care facilities reported that eMAR implementation is low, partly because of cost barriers, and there is a lack of rigorously designed research to inform administrators and clinicians about the effect of eMARs and bar-code medication administration on MEs [ 60 ]. The use of multi-compartment compliance aids is another possible approach to reduce preparation and administration errors. A recent study in London reported that MAE rate was higher with original medication packaging than with multi-compartment compliance aids (risk ratio = 3.9, 95% CI 2.4–6.1) [ 63 ]. Limitations to their use included reduced staff alertness during administration and difficulties in identifying medication [ 63 ].

This review has highlighted that many interventions focusing on the key steps in medicine optimization led to improvement in medication use. However, some components have not been comprehensively evaluated or not in powerful designs such as randomized controlled trials. In much of the literature reviewed, there was an under-representation of aspects of medication use not related to prescribing (including monitoring). This is perhaps not surprising due to the predominance of the prescribing process in healthcare, but other aspects of medication use do require further consideration. Many studies that did focus on prescribing had common intervention components. At the micro-level MR, multidisciplinary work, and more recently, patient-centered care components dominated; at the macro-, guidelines and legislation, mainly for specific medication classes, e.g., antipsychotics, were employed. Improving administration was achieved through utilization of technology.

What was also apparent in the studies examined was the marked heterogeneity in outcome reporting and measurement across studies (Table 2 ). This makes synthesis of findings difficult and highlights the need for a more common approach across studies examining similar research questions. This may be realized through the development and use of core outcome sets (COSs). Two relevant COSs exist, for trials aimed at optimizing prescribing among NHR [ 64 ] and for trials of MR in multi-morbid older patients with polypharmacy [ 65 ]. Several outcomes of these COSs have been under-evaluated (i.e., what to measure), such as pain relief, all-cause mortality, falls, quality of life, hospital admissions and emergency visits to hospital. These are clearly important outcomes for this particular population and for the health systems. It is important that future trials refer to and use a COS. Furthermore, approaches to measurement of outcomes (i.e., how to measure) were also highly variable. PIP was measured in most studies, but a wide range of tools was used. Although many were targeted at older adults, such tools may not be appropriate for NHRs who have a higher degree of frailty. The use of tools that have been specifically developed for those who are frail [ 47 ] or living in residential care (stoppNH [ 66 ]) may be a better option.

System level (macro-level) approaches were implemented in US and Australia, but much less so in Europe. Positive effects were seen with mandatory/legislative initiatives, and it could be argued that these should be considered at the European level. However, there has been a tradition of different countries tackling approaches in nursing home care in different ways which may be a function of different cultural and political contexts [ 67 ]. Many of the concerns around prescribing of key medicines such as antipsychotics and anti-infectives are universal, and a more comprehensive, cross-country approach may be warranted.

At the micro-level, the importance of patient-centered interventions was increasingly recognized. Patient involvement or participation in the interventions was identified in two recent EU studies focusing on psychotropic drugs [ 28 , 29 ], and in one of the studies to improve prescribing for the whole medication regimen [ 18 ]. However, more research on how best to involve NHRs, and NHRs with dementia in particular, is required. In some countries, patient and public involvement is increasingly expected as part of applications for research funding [ 68 ]. A recent study introduced weekly participatory action research sessions. During these, NHRs could discuss NH initiatives and suggest improvement. Results reported a positive NHR experience and an improved quality of life [ 69 ]. However, this is a challenging area as many NHRs will have varying levels of cognitive impairment, which may limit the level of their participation.

This paper focused on a number of specific medication classes which, historically, have been viewed as problematic in this population. With regard to psychotropics, a particular focus has been on reducing the use of antipsychotic drugs, but there was little exploration of any compensatory increases in the use of other sedating psychotropic drugs [ 70 ] or in the use of non-pharmacological approaches. Measurement of clinical and humanistic outcomes was limited and heterogeneous [ 27 ], therefore, a COS for interventions targeting psychotropic/antipsychotic drug use in NHs would be welcome. Indeed, this was also seen with studies focusing on DAPs, with a plethora of scales available, but little overlap to facilitate comparison. Anti-infectives have also been extensively studied in the NH environment. There has been no concerted attempt to introduce macro-level interventions focusing on ASP, which may reflect differing prescribing practices and cultures [ 71 ], but there have been efforts to begin to standardize the important outcomes for ASP interventions [ 72 ].

We selected the medication classes above because of a legacy of concern over inappropriate use. However, other medication classes also deserve specific focus, but have been ignored. Pain control is one of the outcomes of a COS of MR in older people [ 65 ]. Inappropriate prescribing of analgesics, and opioids in particular has been described in NHRs [ 73 – 75 ]. Second, there has been little work focusing on optimizing the use of antithrombotic agents among NHRs. This is an important research gap, as bleeding and thrombotic events are the most frequent ADEs [ 4 ]. Third, data on the deprescribing of medications used for cardiovascular prevention (e.g., statins, aspirin) and for diabetes would also be welcome, as no or very limited data are available [ 76 – 78 ]. Finally, the use of proton-pump inhibitors (PPIs) is highly prevalent and often inappropriate [ 79 , 80 ]. While factors associated with both PPIs use and discontinuation have been described [ 79 , 81 ], we found only one single-center intervention study targeting PPIs deprescribing [ 82 ]. The implementation of a deprescribing guideline was not associated with a statistically significant decrease in PPIs use [ 82 ].

Health information technology (HIT) has the potential to improve medication use in this environment, specifically to reduce the occurrence of medication errors. HIT includes systems such as eMARs, electronic medication management systems, CDSS, electronic health records [ 62 ]. Long-term care facilities have lagged behind other sectors in the adoption of HIT because of the lack of funding [ 62 ]. The eMAR system was one of the most common types of technology implemented. However, this type of technological support did not extend to supporting clinical decision-making. There was little data on the effect of CDSS in NHs, but there is ongoing research on this topic ( 83 ). Its impact in the long-term environment remains to be seen as recent trials on CDSS to optimize prescribing in primary and acute care have shown negative results on clinical outcomes [ 84 , 85 ]. The relevance of alerts and usability seem to be limiting features, and these finding would be important if this technology were implemented in NHs. Other aspects of technological interventions are also lacking a strong evidence base such as the completeness and accuracy of transfer of medication information at transition moments, and the role of telemedicine.

Evidence is lacking regarding the transferability of interventions across countries and across NHs because barriers and enablers differ. Sometimes, culture and context will overwhelm any attempt to implement an approach that has worked else. However, increasingly, more attention is being paid to how interventions are developed by using recognized frameworks such as the Medical Research Council guidance on the complex interventions [ 86 ]. This systematic approach advocates for reference to existing evidence, the use of theory, modeling, pilot/feasibility testing, and implementation. There are now many more examples of interventions being developed using this approach, with a particular emphasis on theories of behavior change [ 87 ], and how barriers and enablers can be recognized [ 88 ]. A large trial evaluating the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of a pharmacist-independent prescribing service in NHs compared to usual general practitioner-led care has been conducted in the UK and is due to report soon [ 89 ]. This trial also has an embedded process evaluation, to try to understand the mechanisms of action associated with the interventions and to explain findings in terms of fidelity to intervention performance [ 89 ]. This rigorous approach to design and evaluation enhances confidence in the conduct and findings of such studies and should be adopted by others seeking to develop and assess interventions in NHs.

The NH setting and its residents have been a focus for a range of interventions targeting the spectrum of optimizing medicines use. This review has highlighted that a number of interventions are effective, but there is a need for further well-designed and large-scale evaluations of intervention components (e.g., health information technology, patient-centered approaches), specific medication classes (e.g., antithrombotic agents) which have been less commonly studied. Interventions targeting medication use aspects other than prescribing (e.g., monitoring) should also be evaluated. Building the evidence base for effective interventions would benefit from the development and uptake of COSs to allow for synthesis of findings. Finally, qualitative studies on barriers and enablers for intervention implementation would enable theory-driven intervention design. This is likely to lead to more robust and rigorous assessments of what is effective in a patient population that has unique health care needs and challenges.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Lorene Zerah for her critical review of the manuscript.

Author contributions

All authors have made substantial contributions to the conception of the review, analysis and interpretation of the data, and writing of the manuscript. Perrine Evrard and Anne Spinewine performed the literature search, selection of relevant articles, and initial synthesis of the data. Perrine Evrard wrote the first draft of the manuscript, and this was then critically reviewed and amended by all co-authors.

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethics approval

As this is a narrative review, no ethical approval was required.

Informed consent

For this type of study, informed consent is not required.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

- 1. Jokanovic N, Tan EC, Dooley MJ, Kirkpatrick CM, Bell JS. Prevalence and factors associated with polypharmacy in long-term care facilities: a systematic review. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2015;16(6):535.e1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2015.03.003. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 2. Spinewine A, Schmader KE, Barber N, Hughes C, Lapane KL, Swine C, et al. Appropriate prescribing in elderly people: how well can it be measured and optimised? Lancet (Lond, Engl) 2007;370(9582):173–184. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61091-5. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 3. Al-Jumaili AA, Doucette WR. Comprehensive literature review of factors influencing medication safety in nursing homes: using a systems model. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2017;18(6):470–488. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2016.12.069. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]