An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

The Benefits of Exercise for the Clinically Depressed

Lynette l craft , ph.d., frank m perna , ed.d., ph.d..

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Corresponding author and reprints: Lynette L. Craft, Ph.D., Division of Psychiatry, Boston University School of Medicine, 85 E. Newton Street, Room M-619, Boston, MA 02118 (e-mail: [email protected] ).

Received 2003 Dec 2; Accepted 2004 Feb 5.

Millions of Americans suffer from clinical depression each year. Most depressed patients first seek treatment from their primary care providers. Generally, depressed patients treated in primary care settings receive pharmacologic therapy alone. There is evidence to suggest that the addition of cognitive-behavioral therapies, specifically exercise, can improve treatment outcomes for many patients. Exercise is a behavioral intervention that has shown great promise in alleviating symptoms of depression. The current review discusses the growing body of research examining the exercise-depression relationship that supports the efficacy of exercise as an adjunct treatment. Databases searched were Medline, PsycLit, PubMed, and SportsDiscus from the years 1996 through 2003. Terms used in the search were clinical depression, depression, exercise, and physical activity . Further, because primary care physicians deliver important mental health services to the majority of depressed patients, several specific recommendations are made regarding counseling these patients on the adoption and maintenance of exercise programs.

Depression affects roughly 9.5% of the U.S. adult population each year, and it is estimated that approximately 17% of the U.S. population will suffer from a major depressive episode at some point in their lifetime. 1, 2 Depression has been ranked as the leading cause of disability in the United States, with over $40 billion being spent each year on lost work productivity and medical treatment related to this illness. 3–6 Recent research suggests that between the years of 1987 and 1997, the rate of outpatient treatment for depression in the United States tripled and that health care costs related to this disorder continue to rise. 7

The vast majority of those suffering from depression first seek treatment from their primary care providers. 8 As such, it has been estimated that the prevalence of depression in primary care settings is 3 times that in community samples, and rates for minor depression and dysthymia are even greater, ranging from 5% to 16% of patients. 8, 9 Depressed patients treated in primary care settings receive predominantly pharmacologic therapy, with fewer receiving adjunct cognitive or behavioral interventions. 7 As a result, it is likely that many of these patients are not educated regarding nonpharmacologic strategies for managing the symptoms of their depression. Treatment of clinical depression can be improved by the addition of cognitive-behavioral therapies, 10 and by exercise. Research has also shown that depressed patients are less fit and have diminished physical work capacity on the order of 80% to 90% of age-predicted norms, 11–14 which in turn may contribute to other physical health problems. Therefore, primary care providers are uniquely positioned to promote behavioral approaches, such as exercise, that complement pharmacologic treatment and may ultimately provide relief from this chronic and often treatment-resistant disorder as well as enhance overall physical well-being. The current review discusses the growing body of research examining the exercise-depression relationship. Databases searched were Medline, PsycLit, PubMed, and SportsDiscus from the years 1996 through 2003. Terms used in the search were clinical depression, depression, exercise, and physical activity .

EXERCISE AND CLINICAL DEPRESSION

Involvement in structured exercise has shown promise in alleviating symptoms of clinical depression. Since the early 1900s, researchers have been interested in the association between exercise and depression. Early case studies concluded that, at least for some, moderate-intensity exercise should be beneficial for depression and result in a happier mood. 15, 16 Further, a relationship between physical work capacity (PWC) and depression appeared to exist, 11–14 but the directional nature of this relationship could not be addressed via case and cross-sectional studies. However, researchers have remained interested in the antidepressant effects of exercise and more recently have utilized experimental designs to study this association.

Many studies have examined the efficacy of exercise to reduce symptoms of depression, and the overwhelming majority of these studies have described a positive benefit associated with exercise involvement. For example, 30 community-dwelling moderately depressed men and women were randomly assigned to an exercise intervention group, a social support group, or a wait-list control group. 17 The exercise intervention consisted of walking 20 to 40 minutes 3 times per week for 6 weeks. The authors reported that the exercise program alleviated overall symptoms of depression and was more effective than the other 2 groups in reducing somatic symptoms of depression (reduction of 2.4 [walking] vs. 0.9 [social support] and 0.4 [control] on the Beck Depression Inventory [BDI], p < .05). Doyne et al. 18 utilized a multiple baseline design to evaluate the effectiveness of interval training in alleviating symptoms of depression. The participants exercised on a cycle ergometer 4 times per week, 30 minutes per session, for 6 weeks. This treatment was compared with an attention-placebo control condition in which subjects listened to audiotapes of “white noise” that they were told was subliminal assertiveness training. Results indicated that the aerobic training program was associated with a clear reduction in depression compared with the control condition, and the improvements in depression were maintained at 3 months post intervention (BDI mean reduction of 14.4 points from baseline, p < .05). In another study, just 30 minutes of treadmill walking for 10 consecutive days was sufficient to produce a clinically relevant and statistically significant reduction in depression (reduction of 6.5 points from baseline on the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression [HAM-D], p < .01). 19

Research also suggests that the benefits of exercise involvement may be long lasting. 20 Depressed adults who took part in a fitness program displayed significantly greater improvements in depression, anxiety, and self-concept than those in a control group after 12 weeks of training (BDI reduction of 5.1 [fitness program] vs. 0.9 [control], p < .001). The exercise participants also maintained many of these gains through the 12-month follow-up period. 20

While most studies have employed walking or jogging programs of varying lengths, the efficacy of nonaerobic exercise has also been assessed. For example, in comparison with a control condition, resistance-training programs reduced symptoms of depression (resistance training vs. control resulted in BDI reduction of 11.5 vs. 4.6, respectively, p < .01, and HAM-D reduction of 7.0 vs. 2.5, respectively, p < .01). 21 Aerobic and nonaerobic modes of exercise have also been compared to determine if certain types of activities are more effective than others. Doyne and colleagues 22 compared the efficacy of running with that of weight lifting. Forty depressed women served as participants and were randomly assigned to running, weight lifting, or a wait-list control group. Participants were asked to complete 4 training sessions each week for the 8 weeks of the program. Depression was assessed at mid- and post-treatment and at 1, 7, and 12 months follow-up. Results indicated that the 2 activities were not significantly different, and that both types of exercise were sufficient to reduce symptoms of depression (running vs. weights vs. control resulted in BDI reduction of 11.1 vs. 13.6 vs. 0.8, respectively, p < .01, and HAM-D reduction of 6.7 vs. 8.7 vs. a 1.0 increase, respectively, p < .01). Further, there were no differences between the 2 treatment groups during follow-up with respect to the percentage of participants who remained nondepressed. Similarly, a study by Martinsen et al. 23 assessed 90 depressed in-patients who were randomly assigned to aerobic or non-aerobic exercise. Aerobic exercise consisted of jogging or brisk walking, and nonaerobic exercise included strength training, relaxation, coordination, and flexibility training. The program was 8 weeks in length, and participants exercised for 60 minutes, 3 times per week. Those in the aerobic group exhibited an increase in PWC compared with those in the nonaerobic group. However, both groups experienced a significant reduction in depression score (p < .001), but there were no significant differences between the groups with respect to the magnitude of change in depression score (p > .10).

Additionally, exercise compares quite favorably with standard care approaches to depression in the few studies that have evaluated their relative efficacy. For example, running has been compared with psychotherapy in the treatment of depression, with results indicating that running is just as effective as psychotherapy in alleviating symptoms of depression (Symptom Checklist-Depression reduction in mean item score of 1.9 [running] vs. 1.6 [therapy], NS). 24 The benefits of running have been compared with cognitive therapy alone and a combination of running and cognitive therapy. 25 Participants in this study were randomly assigned to running only, running and therapy, or cognitive therapy only. The treatment was 10 weeks in length. The running group met 3 times per week and exercised for 20 minutes per session. Those in the therapy-only group met with a therapist for 60 minutes once a week. Those in the combination group received 10 individual sessions with a therapist and also ran 3 times per week. There were no significant differences between these 3 groups, with all groups displaying a significant reduction in depression, and the positive benefits were still present at the 4-month follow-up (BDI reduction of 10.9 [running] vs. 11.0 [therapy] vs. 7.7 [combined]; main effect for time, p < .001; group × time interaction, NS, p > .05).

The efficacy of exercise relative to psychotropic medication has also been investigated. Blumenthal and colleagues 26 randomly assigned 156 moderately depressed men and women to an exercise, medication, or exercise and medication group. Those in the exercise group walked or jogged on a treadmill at 70% to 85% of heart rate reserve for 30 minutes 3 times per week for 16 weeks. Those in the medication group received sertraline, and a psychiatrist evaluated medication efficacy, assessed side effects, and adjusted dosages accordingly at 2, 6, 10, 14, and 16 weeks. Those in the combination group received both medication and exercise prescription according to the procedures described previously. Results showed that while medication worked more quickly to reduce symptoms of depression, there were no significant differences among treatment groups at 16 weeks (HAM-D: F = 0.96, df = 2,153; p = .39; BDI: F = 0.90, df = 2,153; p = .40). The percentage of patients in remission from their depression at 16 weeks did not differ among groups (60.4% [exercise] vs. 68.8% [medication] vs. 65.5% [combination], p = .67). Therefore, exercise was as effective as medication for reducing symptoms of depression in that sample. Interestingly, 10-month follow-up of those participants revealed that exercise group members (70%) had significantly (p = .028) lower rates of depression than those in the medication (48%) or the combination groups (54%). 27 Finally, at 10 months, regular exercise involvement was a significant predictor of lower rates of depression (OR = 0.49, CI = 0.32 to 0.74, p < .01). 26

META-ANALYTIC FINDINGS

While relatively few studies have been described here for illustrative purposes, there are now a large number of studies that support the efficacy of exercise in reducing symptoms of depression. Further, while the early research in this area suffered from a variety of methodological limitations (e.g., small samples, lack of random assignment, lack of control groups), current researchers have addressed these design issues, and presently there are multiple studies that have utilized experimental designs or employed a randomized clinical trial approach. Meta-analysis provides one means of summarizing this growing body of primary research and identifying variables that may moderate the effect of exercise on depression. Effect sizes (ESs) are calculated for each study and weighted to correct for positive bias that can result from small sample sizes. The statistical analyses of these ESs allow the researcher to investigate study and subject characteristics that may moderate the exercise-depression relationship as well as compare subsets of samples from the original studies and make comparisons (e.g., male vs. female, mildly vs. moderately depressed) that were not directly made within each of the individual primary research articles.

There have been several meta-analyses conducted on the literature examining the relationship between exercise and depression. North et al. 28 included 80 studies in their meta-analysis and reported an overall mean ES of −0.53, indicating that exercise reduced depression scores by approximately one half a standard deviation compared with those in comparison groups. That meta-analysis included primary research studies that had examined the exercise-depression relationship in a variety of samples (e.g., college students, medical patients, depressed and mentally ill patients, and normal adults). When those authors analyzed the subgroup of studies that had utilized clinical populations (e.g., substance abusers, post–myocardial infarction patients, hemodialysis patients), they reported an even larger ES of −0.94. However, patients suffering from depression secondary to a medical condition may be qualitatively different from those who suffer from clinical depression as the primary illness. As such, exercise interventions that are effective for medical populations may not be as effective in treating depression when it is the primary disorder. 29

Craft and Landers 30 attempted to further clarify this relationship and included only studies in which individuals diagnosed with clinical depression served as participants. Thirty studies were included in that meta-analysis, and an overall mean ES of −0.72 was reported. Several variables related to study quality, subject characteristics, and exercise program characteristics were coded and examined in an attempt to determine potential moderators of this relationship. Interestingly, exercise program characteristics such as duration, intensity, frequency, and mode of exercise did not moderate the effect. In fact, only the length of the exercise program was a significant moderator, with programs 9 weeks or longer being associated with larger reductions in depression. Further, exercise was equally effective across a variety of patient subgroups. For example, subject characteristics such as age, gender, and severity of depression did not emerge as significant moderators. Finally, when compared with other traditional treatments for depression, exercise was just as beneficial and not significantly different from psychotherapy, pharmacologic therapy, and other behavioral interventions. 30

Lawlor and Hopker 31 more recently conducted a meta-analysis that included only randomized controlled trials of clinically depressed patients. Fourteen studies were included in their meta-analysis. They reported an overall mean ES of −1.1 for exercise interventions compared with no-treatment control groups. Exercise was also as effective as cognitive therapy in alleviating symptoms of depression, with a nonsignificant ES of −0.3 emerging.

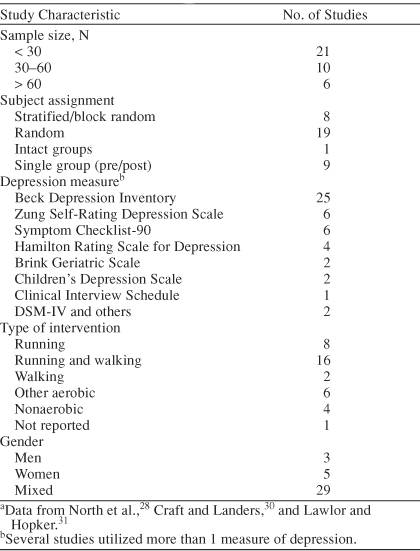

Analyses of subsamples within these meta-analyses indicate that exercise is effective for both men and women of all ages as well as those who are initially more severely depressed. Further, comparison of exercise program characteristics across the studies yielded nonsignificant ESs, indicating that exercise need not be lengthy or intense and that fitness gains are not necessary for patients to experience positive benefits. Therefore, in light of this additional meta-analytic support, researchers have begun to recommend that depressed individuals should adopt physically active lifestyles to help manage their symptoms. 30, 32, 33 Table 1 provides basic characteristics of the studies utilizing clinical populations that were included in the 3 meta-analyses discussed above. 28, 30, 31 Readers are referred to each of the meta-analyses for additional information regarding individual primary research articles. Further, a review by Dunn and colleagues 34 includes a summary of study and participant characteristics for quasiexperimental and experimental designs.

Characteristics of 37 Studies Included in Exercise and Depression Meta-Analyses a

The data from the 3 meta-analyses discussed previously 28, 30, 31 resulted in overall ESs of −0.72, −0.94, and −1.1. Converting these ESs to a binomial effect size display allows one to examine the practical clinical significance of these effect sizes. 35 These values reflect an increase in success rate due to treatment (i.e., exercise) of 67%, 71%, and 74%, respectively, and such promising treatment outcomes are notable. In medical settings, clinical guidelines suggest that a 50% reduction in symptoms during the treatment phase is considered a treatment response. Researchers have argued that this criterion is more clinically relevant than statistically significant results, which can occur even if the participants have not experienced a 50% reduction in the symptoms of their depression. 34 Therefore, even when using this more clinically relevant guideline, the meta-analytic data provide support for the efficacy of exercise in reducing symptoms of depression. While this discussion is not meant to argue against the use of antidepressant medication or psychological therapies, there is strong evidence to advocate the use of exercise as a potentially powerful adjunct to existing treatments.

PROPOSED MECHANISMS FOR THE EXERCISE-DEPRESSION RELATIONSHIP

While the research is consistent and points to a relationship between exercise and depression, the mechanisms underlying the antidepressant effects of exercise remain unclear. Several credible physiologic and psychological mechanisms have been described, such as the thermogenic hypothesis, 36 the endorphin hypothesis, 37, 38 the monoamine hypothesis, 39–42 the distraction hypothesis, 43 and the enhancement of self-efficacy. 29, 43–46 However, there is little research evidence to either support or refute most of these theories.

Thermogenic Hypothesis

The thermogenic hypothesis suggests that a rise in core body temperature following exercise is responsible for the reduction in symptoms of depression. DeVries 36 explains that increases in temperature of specific brain regions, such as the brain stem, can lead to an overall feeling of relaxation and reduction in muscular tension. While this idea of increased body temperature has been proposed as a mechanism for the relationship between exercise and depression, the research conducted on the thermogenic hypothesis has examined the effect of exercise only on feelings of anxiety rather than depression. 36, 47, 48

Endorphin Hypothesis

The endorphin hypothesis predicts that exercise has a positive effect on depression due to an increased release of β-endorphins following exercise. Endorphins are related to a positive mood and an overall enhanced sense of well-being. This line of research has not been without criticism. The debate remains as to whether plasma endorphins reflect endorphin activity in the brain. Some 37, 38 have argued that even if peripheral endorphin levels are not reflective of brain chemistry, they could still be associated with a change in mood or feelings of depression. Several studies have shown increases in plasma endorphins following acute and chronic exercise 49–51 ; yet, it remains unclear if these elevations in plasma endorphins are directly linked to a reduction in depression. Lastly, the phenomenon of runner's high, often attributed to endorphin release, is not blocked by naloxone injection, an opiate antagonist. 52, 53

Monoamine Hypothesis

The monoamine hypothesis appears to be the most promising of the proposed physiologic mechanisms. This hypothesis states that exercise leads to an increase in the availability of brain neurotransmitters (e.g., serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine) that are diminished with depression. These neurotransmitters increase in plasma and urine following exercise, but whether exercise leads to an increase in neurotransmitters in the brain remains unknown. 40–42 Animal studies suggest that exercise increases serotonin and norepinephrine in various brain regions, 39, 54–56 but, to date, this relationship has not been studied in humans.

Therefore, while several physiologic mechanisms remain plausible, methodological difficulties have prevented this line of research from advancing. Martinsen 57 discusses how testing biochemical hypotheses is often difficult in humans due to the invasive procedures necessary to obtain samples (e.g., spinal taps for cerebrospinal fluid samples). Further, biochemical samples obtained from blood or other bodily fluids may not directly reflect the activity of these compounds in the brain. 39 Hopefully, with the advent of new less invasive neuroimaging techniques, future researchers can examine whether exercise leads to the neurochemical changes in the brain predicted by these physiologic hypotheses.

Distraction Hypothesis

Several psychological mechanisms have also been proposed. As was the case with the physiologic mechanisms, many of these theories have not been tested extensively. The distraction hypothesis suggests that physical activity serves as a distraction from worries and depressing thoughts. 43 In general, the use of distracting activities as a means of coping with depression has been shown to have a more positive influence on the management of depression and to result in a greater reduction in depression than the use of more self-focused or introspective activities such as journal keeping or identifying positive and negative adjectives that describe one's current mood. 58, 59

Exercise has been compared with other distracting activities such as relaxation, assertiveness training, health education, and social contact. 17, 18, 23, 60 Results have been inconclusive, with exercise being more effective than some activities and similar to others in its ability to aid in the reduction of depression. However, exercise is known to increase positive affect, which is diminished in depressed patients and is not augmented by distraction activities. The diminished capacity to experience positive affect is an essential distinguishing symptom in clinical depression.

Self-Efficacy Hypothesis

The enhancement of self-efficacy through exercise involvement may be another way in which exercise exerts its antidepressant effects. Self-efficacy refers to the belief that one possesses the necessary skills to complete a task as well as the confidence that the task can actually be completed with the desired outcome obtained. Bandura 36 describes how depressed people often feel inefficacious to bring about positive desired outcomes in their lives and have low efficacy to cope with the symptoms of their depression. This can lead to negative self-evaluation, negative ruminations, and faulty styles of thinking. It has been suggested that exercise may provide an effective mode through which self-efficacy can be enhanced based on its ability to provide the individual with a meaningful mastery experience. Research examining the association between physical activity and self-efficacy in the general population has focused predominantly on the enhancement of physical self-efficacy and efficacy to regulate exercise behaviors. The relationship between exercise and self-efficacy in the clinically depressed has received far less attention. The findings of the few studies that have examined this relationship have been equivocal as to whether exercise leads to an enhancement of generalized feelings of efficacy. 23, 61 However, 1 recent study 62 has reported that involvement in an exercise program was associated with enhanced feelings of coping self-efficacy, which, in turn, were inversely related to feelings of depression.

More research is needed to determine which, if any, of the mechanisms described herein are important moderators of the exercise effect. It is highly likely that a combination of biological, psychological, and sociological factors influence the relationship between exercise and depression. This is consistent with current treatment for depression in which the effects of pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy on depression are additive and address biological, psychological, and sociological aspects of the patient. There may also be individual variation in the mechanisms or combination of mechanisms mediating this relationship. 32 Additionally, different mechanisms may be important at specific times in the natural course of depression. Until more is known about the possible mechanisms, this relationship may be best studied utilizing a biopsychosocial approach.

PRACTICAL CONSIDERATIONS

With increasing evidence to support the efficacy of this behavioral intervention in reducing symptoms of depression, we encourage primary care providers to recommend exercise involvement to their depressed patients. However, if physicians are to recommend physical activity as adjunct therapy, there are a few practical considerations that should be addressed. First, patients with depression are typically sedentary and may lack motivation to begin an exercise program. The American College of Sports Medicine 63 has made the recommendation that all adults should exercise at least 30 minutes per day, on all or most (5) days per week, at a moderate-vigorous intensity. Such a recommendation is likely to be overwhelming to someone who is currently sedentary and depressed. Based on the meta-analytic findings in this area, an exercise prescription of 20 minutes per day, 3 times per week, at a moderate intensity is sufficient to significantly reduce symptoms of depression. 30 Therefore, we suggest that physicians begin with this prescription as an initial recommendation.

Physicians should counsel patients to begin slowly and choose an enjoyable mode of exercise. For many people, walking is often a cost-effective option, and the physician should ask patients to identify a safe place to walk and a place to walk indoors during inclement weather (e.g., a shopping mall). The primary care provider may want to encourage the patient to first work on the frequency of his or her exercise activities, that is, setting a goal of 3 exercise sessions per week, at a comfortable pace, for a manageable length of time (e.g., 10 minutes). Once the patient becomes confident that the exercise frequency is under his or her control, the duration of the exercise bout can gradually be increased.

The final exercise characteristic that should be addressed is the exercise intensity. Reminding patients that exercise need not be lengthy or intense to enhance mood is also a good strategy. For patients with a low level of fitness, which characterizes most depressed patients, moderate-intensity exercise (60%–80% maximum heart rate) generally produces greater enjoyment than more intense activity. 64–69 Further, in the general population, beginning a moderate-intensity exercise program is associated with roughly one half the dropout rate of beginning a vigorous-intensity exercise program. 70 Therefore, suggesting that patients begin with lower-intensity exercise activities that they find enjoyable should result in a more positive exercise experience for the patient and increase the likelihood of maintained exercise involvement.

Some data suggest that exercise may also improve sleep quality for some patients. 71, 72 However, at this time, causal inferences cannot be made, and specific sleep data for depressed patients are needed. Results are equivocal as to whether time of day of exercise plays a role in this relationship. As such, patients should be encouraged to exercise at a time that is most convenient for them. For some patients, depressive symptoms worsen later in the day and exercise may be easier to schedule and manage if conducted in the morning or afternoon. With limited data to support the notion that early evening exercise facilitates better sleep, physicians are encouraged to counsel patients that sleep quality may be improved by exercise, and patients should exercise when it is most convenient or feels best for them.

Briefly instructing patients on the benefits of using self-monitoring techniques (exercise logs, pedometers) and setting small, achievable goals can also be significant points of discussion when patients are adopting exercise programs. In the general population, research has shown that addressing a number of key factors specific to the individual (e.g., exercise self-efficacy, social support for exercise, and perceived barriers to exercise), as well as continued brief supportive contact with the researcher or physician, can increase the rate of adherence to the exercise program by up to 25%. 73–76 The use of self-monitoring and brief follow-up contact with the physician is aimed at increasing the patient's awareness of the immediate rewards of exercise, which is more effective in promoting adherence than focusing on distant outcomes. Therefore, primary care physicians are encouraged to regularly inquire (e.g., during office visits) about exercise involvement and reinforce any positive benefits the patient reports experiencing.

The mechanisms underlying the antidepressant effects of exercise remain in debate; however, the efficacy of exercise in decreasing symptoms of depression has been well established. Data regarding the positive mood effects of exercise involvement, independent of fitness gains, suggest that the focus should be on frequency of exercise rather than duration or intensity until the behavior has been well established. The addition of self-monitoring techniques may increase awareness of the proximal benefits of exercise involvement, which is generally reinforcing to the patient.

Physician advice is likely to go a long way toward providing motivation and support for exercise. Follow-up contact may also be important during exercise adoption. While this follow-up may present a time challenge to the provider, less time-consuming interactions such as brief telephone contact and automated telephone contact have been shown to increase adherence to exercise programs. 77–80 Finally, it is interesting to note that while depression may be an additional risk factor for exercise noncompliance, reported drop-out rates among depressed patients are not too different from those in the general population. 13, 21–23, 26

Drug names: naloxone (Suboxone, Narcan, and others), sertraline (Zoloft).

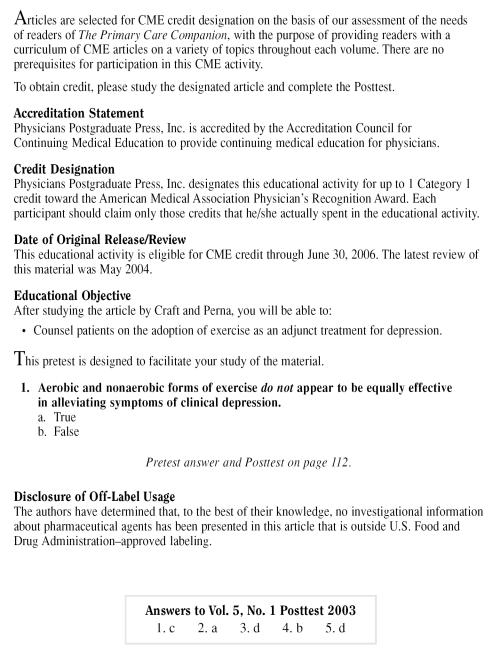

Pretest and Objectives

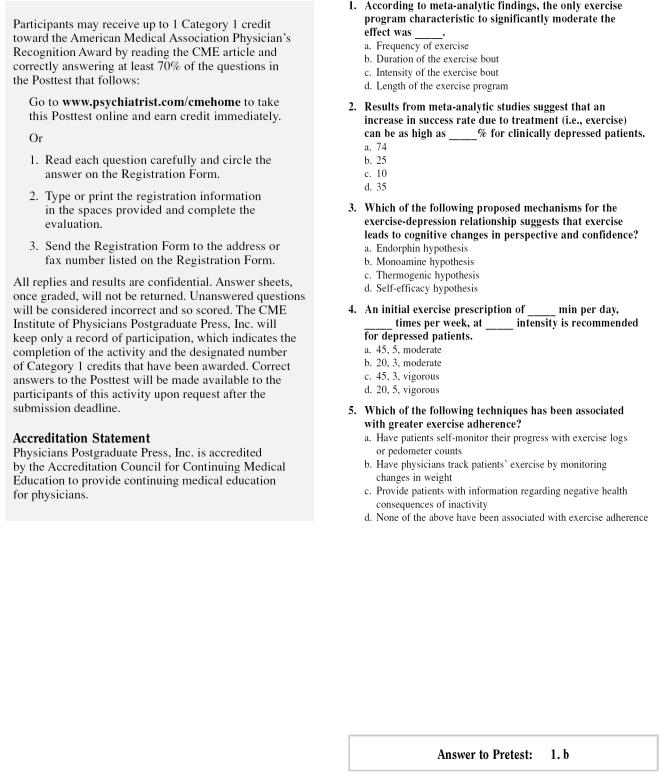

Instructions and Posttest

Registration and Evaluation

This manuscript was partially supported by the National Institutes of Health General Clinical Research Center Grant #M01RR005333 to Boston University School of Medicine.

In the spirit of full disclosure and in compliance with all ACCME Essential Areas and Policies, the faculty for this CME activity were asked to complete a full disclosure statement. The information received is as follows: Drs. Craft and Perna have no significant commercial relationships to disclose relative to the presentation.

- Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, and Zhao S. et al. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994 51:8–19. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- National Institute of Mental Health. The numbers count: mental disorders in America. Available at: http://www.nimh.gov . Accessed Sept 3, 2003. [ Google Scholar ]

- Broadhead WE, Blazer DG, and George LK. et al. Depression, disability days, and days lost from work in a prospective epidemiologic survey. JAMA. 1990 264:2524–2528. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Murray CJ, Lopez AD. Evidence-based health policy lessons form the Global Burden of Disease Study. Science. 1996;274:740–743. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5288.740. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- World Health Organization. Depression. Available at http://www.who.org . Accessed Nov 15, 2003. [ Google Scholar ]

- Zerihun M. Depression drains workplace productivity. Available at: http://www.depressionnet.org . Accessed Oct 31, 2001. [ Google Scholar ]

- Olfson M, Marcus SC, and Druss B. et al. National trends in the outpatient treatment of depression. JAMA. 2002 287:203–209. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pincus JA, Pechura CM, and Elinson L. et al. Depression in primary care: linking clinical and systems strategies. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2001 23:311–318. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Frank E, Rucci P, and Stat D. et al. Correlates of remission in primary care patients treated for minor depression. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2002 24:12–19. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Young JE, Weinberger AD, and Beck AT. Cognitive therapy for depression. In: Barlow DH, ed. Clinical Handbook of Psychological Disorders, Third Edition. New York, NY:Guilford Press. 2001 [ Google Scholar ]

- Morgan WP. Selected physiological and psychomotor correlates of depression in psychiatric patients. Res Q. 1968;30:1037–1043. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Morgan WP. A pilot investigation of physical working capacity in depressed and nondepressed males. Res Q. 1969;40:859–861. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Martinsen EW, Medhus A, Sandvik L. Effects of aerobic exercise on depression: a controlled study [abstract] Br Med J (Clin Res ED) 1985;291:109. doi: 10.1136/bmj.291.6488.109. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Martinsen EW, Strand J, and Paulsson G. et al. Physical fitness levels in patients with anxiety and depressive disorders. Int J Sports Med. 1989 10:58–61. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Franz SI, Hamilton GV. The effects of exercise upon retardation in conditions of depression. Am J Psychiatry. 1905;62:239–256. [ Google Scholar ]

- Vaux CL. A discussion of physical exercise and recreation. Am J Phys Med. 1926;6:303–333. [ Google Scholar ]

- McNeil JK, LeBlanc EM, Joyner M. The effect of exercise on depressive symptoms in the moderately depressed elderly. Psychol Aging. 1991;6:487–488. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.6.3.487. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Doyne EJ, Chambless DL, Beutler LE. Aerobic exercise as a treatment for depression in women. Behav Ther. 1983;14:434–440. [ Google Scholar ]

- Dimeo F, Baurer M, and Varahram I. et al. Benefits from aerobic exercise in patients with major depression: a pilot study. Br J Sports Med. 2001 35:114–117. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- DiLorenzo TM, Bargman EP, and Stucky-Ropp R. et al. Long-term effects of aerobic exercise on psychological outcomes. Prev Med. 1999 28:75–85. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sing NA, Clements KM, Fiatarone MA. A randomized controlled trial of progressive resistance training in depressed elders. J Gerontol. 1997;52:M27–M35. doi: 10.1093/gerona/52a.1.m27. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Doyne EJ, Ossip-Klein DJ, and Bowman ED. et al. Running versus weight lifting in the treatment of depression. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1987 55:748–754. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Martinsen EW, Hoffart A, Solberg O. Comparing aerobic and nonaerobic forms of exercise in the treatment of clinical depression: a randomized trial. Compr Psychiatry. 1989;30:324–331. doi: 10.1016/0010-440x(89)90057-6. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Greist JH, Klein MH, and Eischens RR. et al. Running as treatment for depression. Compr Psychiatry. 1979 20:41–54. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Fremont J, Craighead LW. Aerobic exercise and cognitive therapy in the treatment of dysphoric moods. Cognit Ther Res. 1987;11:241–251. [ Google Scholar ]

- Blumenthal JA, Babyak MA, and Moore KA. et al. Effects of exercise training on older patients with major depression. Arch Intern Med. 1999 159:2349–2356. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Babyak M, Blumenthal JA, and Herman S. et al. Exercise treatment for major depression: maintenance of therapeutic benefit at 10 months. Psychosom Med. 2000 62:633–638. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- North TC, McCullagh P, Tran ZV. Effects of exercise on depression. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 1990;18:379–415. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Simons AD, McGowan CR, and Epstein LH. et al. Exercise as a treatment for depression: an update. Clin Psychol Rev. 1985 5:553–568. [ Google Scholar ]

- Craft LL, Landers DM. The effect of exercise on clinical depression and depression resulting from mental illness: a meta-analysis. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 1998;20:339–357. [ Google Scholar ]

- Lawlor DA, Hopker SW. The effectiveness of exercise as an intervention in the management of depression: systematic review and meta-regression analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMJ. 2001;322:763–767. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7289.763. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Fox KR. The influence of physical activity on mental well-being. Public Health Nutr. 1999;2:411–418. doi: 10.1017/s1368980099000567. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Mutrie N. The relationship between physical activity and clinically-defined depression. In: Biddle SJH, Fox KR, Boutcher SH, eds. Physical Activity and Psychological Well-Being. London, England: Routledge. 2000 [ Google Scholar ]

- Dunn AL, Trivedi MH, O'Neil HA. Physical activity dose-response effects on outcomes of depression and anxiety. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2000;33:s587–s597. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200106001-00027. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Rosenthal R. The evaluation of meta-analytic procedures and meta-analytic results. In: Rosenthal R, ed. Meta-Analytic Procedures for Social Research. Newbury Park, Calif: Sage. 1984 [ Google Scholar ]

- deVries HA. Tranquilizer effects of exercise: a critical review. Phys Sportsmed. 1981;9:46–55. doi: 10.1080/00913847.1981.11711206. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Johnsgard KW. The Exercise Prescription for Anxiety and Depression. New York, NY: Plenum Publishing. 1989 [ Google Scholar ]

- Morgan WP. Affective beneficience of vigorous physical activity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1985;17:94–100. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dishman RK. The norepinephrine hypothesis. In: Morgan WP, ed. Physical Activity and Mental Health. Washington, DC: Taylor & Francis. 1997 [ Google Scholar ]

- Ebert MH, Post RM, Goodwin FK. Effect of physical activity on urinary MHPG excretion in depressed patients [abstract] Lancet. 1972;2:766. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(72)92064-8. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Post RM, Kotin J, and Goodwin FK. et al. Psychomotor activity and cerebro-spinal fluid amine metabolites in affective illness. Am J Psychiatry. 1973 130:67–72. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Tang SW, Stancer HC, and Takahashi S. et al. Controlled exercise elevates plasma but not urinary MHPG and VMA. Psychiatry Res. 1981 4:13–20. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Leith LM. Foundations of Exercise and Mental Health. Morgantown, WVa: Fitness Information Technology. 1994 [ Google Scholar ]

- Bandura A. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control. New York, NY: WH Freeman & Company. 1997 [ Google Scholar ]

- Gleser J, Mendelberg H. Exercise and sport in mental health: a review of the literature. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci. 1990;27:99–112. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Martinsen EW. Benefits of exercise for the treatment of depression. Sports Med. 1990;9:380–389. doi: 10.2165/00007256-199009060-00006. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Morgan WP. Exercise and mental health. In: Dishman RK, ed. Exercise Adherence: Its Impact on Public Health. Champaign, Ill: Human Kinetics. 1988 [ Google Scholar ]

- Raglin JS, Morgan WP. Influence of exercise and quiet rest on state anxiety and blood pressure. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1985;19:456–463. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bortz WM, Angwin P, Mefford IN. Catecholamines, dopamine, and endorphin levels during extreme exercise. N Engl J Med. 1981;305:466–467. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Carr DB, Bullen BA, and Skrinar G. et al. Physical conditioning facilitates the exercise-induced secretion of beta-endorphin and beta-lipotropin in women. N Engl J Med. 1981 305:597–617. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Farrell PA, Gates WK, Maksud MG. Increases in plasma beta-endorphin/beta-lipotropin immunoreactivity after treadmill running in humans. J Appl Physiol. 1982;52:1245–1249. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1982.52.5.1245. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Markoff RA, Ryan P, Young T. Endorphins and mood changes in long-distance running. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1982;14:11–15. doi: 10.1249/00005768-198201000-00002. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- McMurray RG, Berry MJ, Hardy CJ. Physiologic and psychologic responses to a low dose of naloxone administered during prolonged running. Ann Sports Med. 1988;4:21–25. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ransford CP. A role for amines in the antidepressant effect of exercise: a review. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1982;14:1–10. doi: 10.1249/00005768-198201000-00001. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dunn AL, Reigle TG, and Youngstedt SD. et al. Brain norepinephrine and metabolites after treadmill training and wheel running in rats. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1996 28:204–209. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Jacobs BL. Serotonin, motor activity and depression-related disorders. Am Sci. 1994;82:456–463. [ Google Scholar ]

- Martinsen EW. The role of aerobic exercise in the treatment of depression. Stress Med. 1987;3:93–100. [ Google Scholar ]

- Morrow J, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Effects of responses to depression on the remediation of depressive affect. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1990;58:519–527. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.58.3.519. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Morrow J. A prospective study of depression and posttraumatic stress symptoms after a natural disaster: the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1991;61:115–121. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.61.1.115. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Klein MH, Greist JH, and Gurman AS. et al. A comparative outcome study of group psychotherapy vs. exercise treatments for depression. Int J Ment Health. 1985 13:148–177. [ Google Scholar ]

- Brown SW, Welsh MC, and Labbe EE. et al. Aerobic exercise in the psychological treatment of adolescents. Percept Mot Skills. 1992 74:555–560. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Craft LL. Exercise and clinical depression: examining two psychological mechanisms. Psychol Sport Exerc. In press. [ Google Scholar ]

- American College of Sports Medicine. The recommended quantity and quality of exercise for developing and maintaining cardiorespiratory and muscular fitness, and flexibility in healthy adults: position stand. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1998;30:975–991. doi: 10.1097/00005768-199806000-00032. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Berger BG, Owen DR. Relation of low and moderate intensity exercise with acute mood change in college joggers. Percept Mot Skills. 1998;87:611–621. doi: 10.2466/pms.1998.87.2.611. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hardy CJ, Rejeski WJ. Not what, but how one feels: the measurement of affect during exercise. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 1989;11:304–317. [ Google Scholar ]

- McGowan RW, Talton BJ, Thompson M. Changes in scores on the Profile of Mood States following a single bout of physical activity: heart rate and changes in affect. Percept Mot Skills. 1996;83:859–866. doi: 10.2466/pms.1996.83.3.859. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Moses J, Steptoe A, and Mathews A. et al. The effects of exercise training on mental well-being in the normal population: a controlled trial. J Psychosom Res. 1989 33:47–61. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Parfitt G, Eston R, Connolly D. Psychological affect at different ratings of perceived exertion in high-and low-active women: a study using a production protocol. Percept Mot Skills. 1996;82:1035–1042. doi: 10.2466/pms.1996.82.3.1035. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Steptoe A, Cox S. Acute effects of aerobic exercise on mood. Health Psychol. 1988;7:329–340. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.7.4.329. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sallis JF, Haskell WL, Fortmann SP. Predictors of adoption and maintenance of physical activity in a community sample. Prev Med. 1986;15:331–334. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(86)90001-0. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Driver HS, Taylor SR. Exercise and sleep. Sleep Med Rev. 2000;4:387–402. doi: 10.1053/smrv.2000.0110. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Youngstedt SD, O'Connor PJ, Dishman RK. The effects of acute exercise on sleep: a quantitative synthesis. Sleep. 1997;20:203–214. doi: 10.1093/sleep/20.3.203. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Buckworth J, Wallace LS. Application of the transtheoretical model to physically active adults. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2002;42:360–367. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Duncan KA, Pozehl B. Staying on course: the effects of an adherence facilitation intervention on home exercise participation. Prog Cardiovasc Nurs. 2002;17:59–65. doi: 10.1111/j.0889-7204.2002.01229.x. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- King AL, Taylor CB, and Haskell WL. et al. Strategies for increasing early adherence to and long-term maintenance of home-based exercise training in healthy middle-aged men and women. Am J Cardiol. 1988 61:628–632. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Writing Group for the Activity Counseling Trial Research Group. Effects of physical activity counseling in primary care: the Activity Counseling Trial: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2001;286:677–687. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.6.677. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Albright CL, Cohen S, and Gibbons L. et al. Incorporating physical activity advice into primary care: physician delivered advice within the activity counseling trial. Am J Prev Med. 2000 18:225–234. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Calfas KJ, Long BJ, and Sallis JR. et al. A controlled trial of physician counseling to promote the adoption of physical activity. Prev Med. 1996 25:225–233. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Green BB, McAfee T, and Hindmarsh M. et al. Effectiveness of telephone support in increasing physical activity levels in primary care patients. Am J Prev Med. 2002 22:177–183. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pinto BM, Friedman R, and Marcus BH. et al. Effects of a computer-based telephone counseling system on physical activity. Am J Prev Med. 2002 23:113–120. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- View on publisher site

- PDF (108.8 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

Is Distraction an Adaptive or Maladaptive Strategy for Emotion Regulation? A Person-Oriented Approach

- Open access

- Published: 07 September 2016

- Volume 39 , pages 117–127, ( 2017 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Martin Wolgast 1 &

- Lars-Gunnar Lundh 1

13k Accesses

73 Citations

75 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Distraction is an emotion regulation strategy that has an ambiguous status within cognitive-behavior therapy. According to some treatment protocols it is counterproductive, whereas according to other protocols it is seen as a quite useful strategy. The main purpose of the present study was to test the hypothesis that distraction is adaptive when combined with active acceptance, but maladaptive when combined with avoidant strategies. A non-clinical community sample of adults ( N = 638) and a clinical sample ( N = 172) completed measures of emotion regulation and well-being. Hierarchical cluster analysis was used to identify subgroups with different profiles on six emotion regulation variables, and these subgroups were then compared on well-being (positive and negative emotionality, and life quality) and on clinical status. A nine-cluster solution was chosen on the basis of explained variance and homogeneity coefficients. Two of these clusters had almost identical scores on distraction, but showed otherwise very different profiles (distraction combined with acceptance vs. distraction combined with avoidance). The distraction-acceptance cluster scored significantly higher than the distraction-avoidance cluster on all measures of well-being; it was also under-represented in the clinical sample, whereas the distraction-avoidance cluster was over-represented. Limitations include a cross-sectional design, and use of self-report measures. The findings suggest that distraction may be either adaptive or maladaptive, depending on whether it is combined with an attitude of acceptance or avoidance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Construct validity of brief difficulties in emotion regulation scale and its revised version: evidence for a general factor

Which Emotion Regulation Strategies are Most Associated with Trait Emotion Dysregulation? A Transdiagnostic Examination

Development and validation of a brief version of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale: the ders-16.

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Difficulties in emotion regulation are increasingly being incorporated into models of psychopathology, and are the direct target of treatment interventions in several recent treatment protocols (Gratz and Tull 2011 ; Barlow et al. 2011 ; Berking et al. 2008 ; Linehan 1993a ; Lynch et al. 2007 ).

An important question in this area concerns the usefulness of strategies focusing on changing versus accepting emotional experiences (e.g. Hayes et al. 1999 ; Mathews 2006 ; Clark 1999 ; Arch and Craske 2008 ; Hayes 2008 ; Hofmann and Asmundson 2008 ). On the one hand, models emphasizing the value of cognitive change strategies are consistent with evidence that the emotional reactions of humans depend to a considerable extent on the way situations or experiences are cognitively construed or interpreted (e.g. Murphy and Zajonc 1993 ; LeDoux 1993 ; Russel 2003 ). From the perspective of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT; Hayes et al. 1999 ) on the other hand, efforts to change or otherwise control emotions or thoughts run the risk of maintaining an inner struggle with these events (Hayes 2008 ), that leads to suffering and impaired functioning (Hayes et al. 1999 ). Instead, in ACT, the focus is on learning to observe and accept dysfunctional emotional experiences, in order to become free of this inner struggle.

An important part of the theoretical discussion regarding the relative value of cognitive change and acceptance strategies concern how these approaches or concepts relate to each other. In the discussion regarding these matters, some writers have proposed that acceptance and cognitive change strategies show considerable similarities and achieve similar outcomes (Arch and Craske 2008 ), whereas others see them as distinct strategies or approaches that are mutually exclusive (Blackledge and Hayes 2001 ), and still others view them as different but compatible forms of emotion regulation intervening at different points in the emotion generating process (Hofmann and Asmundson 2008 ).

In a previous study, Wolgast et al. ( 2012 ) explored the constructs of cognitive restructuring and acceptance by using items from well-established measures of these respective constructs in order to identify subcategories or conceptual nuances in this area. Exploratory factor analyses in a non-clinical sample resulted in a six-factor solution. Three of these factors (“Active Acceptance”, “Thought Avoidance” and “Resignation”) loaded on a higher order factor of “Acceptance”, whereas three other factors (“Constructive Refocusing”, “Cognitive Reappraisal” and “Distractive Refocusing”) loaded on a higher order factor of “Cognitive Restructuring”. The factors are described further below in the “methods” section. Interestingly, “Active Acceptance” also loaded significantly on the “Cognitive Restructuring” factor, whereas “Constructive Refocusing” also loaded on the “Acceptance” factor. This factor structure was validated by confirmatory factor analyses in another non-clinical sample and in a clinical sample. In sum, these findings indicate that acceptance and cognitive restructuring should not be regarded as unitary and non-related constructs, but rather as partly overlapping general dimensions of emotion regulation consisting of several sub-constructs.

In studying these six emotion regulation factors for their associations with well-being (positive and negative emotionality, life quality, and clinical status), Wolgast et al. ( 2012 ) found that Constructive Refocusing was most consistently positively associated with aspects of well-being, but that also Active Acceptance and Cognitive Reappraisal showed positive associations of this kind. Thought Avoidance and Resignation, as expected, showed consistent negative associations with all aspects of well-being. The strategy of Distractive Refocusing, however, stood out as not showing any significant associations with positive or negative emotionality, or with life quality, and showing only a weak association with clinical status (the non-clinical group using more distractive refocusing than the clinical group).

These results with regard to Distractive Refocusing are interesting in view of the ambiguous status of distraction strategies within cognitive behavioral therapies. In some protocols, distraction is seen as counter-productive (e.g. Craske and Barlow 2008 ). In other protocols, however, as for example in Dialectic Behavior Therapy (DBT; Linehan 1993a ) and in Gratz’ (Gratz and Tull 2011 ) Emotion Regulation Group Treatment (ERGT), distraction is taught as a valid strategy for regulating aversive emotions. One possibility is that distraction is adaptive in some contexts, and maladaptive in others. If so, this might also explain the weak associations between Distractive Refocusing and well-being in our previous study (Wolgast et al. 2012 ), when measured as a variable averaged over different context, based on questions about what the respondents generally do or think when faced with aversive emotions. An alternative possible explanation for these weak associations, however, is that Distractive Refocusing simply represents an emotion regulation strategy that is neither particularly effective nor maladaptive.

In connection to this, it is interesting to note that when distraction is taught in DBT (Linehan 1993b ) or ERGT (Gratz 2010 ), it is done in a context which strongly emphasizes the importance of acceptance and willingness in relation to aversive experiences. For example, as Linehan ( 1993b ) teaches distraction to clients, it is done as an example of a distress tolerance skill that may be important for survival in situations of crisis. As Gratz ( 2010 ) describes it, distraction involves redirecting attention towards something else for a short period of time , and is therefore quite compatible with a willingness to come into contact with the avoided emotion in the near future. As she puts it, if distraction is used in this way , it can be a useful strategy for taking the edge off painful emotions.

This suggests the hypothesis that distraction is an adaptive strategy if it is used in the context of an accepting attitude to painful emotions, whereas it is maladaptive if used in the context of experiential avoidance . That is, distraction would be adaptive if it is only a matter of temporarily redirecting one’s attention toward something else for a short period of time, with the intention of getting back into contact with that emotion or the challenging situation in the near future. On the other hand, if distraction is used as part of a generally avoidant strategy, it is likely to be maladaptive. The main purpose of the present study was to test this hypothesis by comparing the well-being of (1) individuals who use distraction in combination with acceptance and (2) individuals who use distraction in combination with experiential avoidance. To test this hypothesis, we used a person-oriented approach to reanalyze the data that were analyzed by a variable-oriented approach in the study by Wolgast et al. ( 2012 ), which we believe is justified given that we use an entirely different approach to data analysis, test distinctly different hypotheses and present completely novel results compared to the previous study.

A general limitation of the kind of variable-oriented approach that was used in the previous study is that it tells us nothing about how different strategies are combined at the level of the individual. This issue is of theoretical importance, among other things, because it bears on the question of whether different strategies (e.g., cognitive restructuring strategies and acceptance strategies) are readily combined or contradictory. In addition, by identifying subgroups of individual who share the same profile of scores on the emotion regulation variables we may not only see how these different strategies are combined in different individuals and how frequent such combinations are, but also how these different profiles or patterns relate to measures of psychological well-being. A second purpose of the present study was therefore to explore these issues more generally, by contrasting alternative hypotheses about the effects of combining acceptance and cognitive restructuring strategies, and the effects of lacking these emotion regulation strategies.

Based on the theoretical discussion summarized above, we expected to find one subgroup of individuals who rely on acceptance strategies but not on cognitive restructuring, another subgroup of individuals who rely on cognitive restructuring but not on acceptance, and a third subgroup of individuals who use both cognitive restructuring and acceptance. As to their association with psychological well-being, we may contrast three hypotheses: (1) The equifinality hypothesis : If acceptance and cognitive change strategies represent strategies with considerable similarities that achieve similar outcomes ( e.g., Arch and Craske 2008 ), all three subgroups should be equally high on psychological well-being, and be overrepresented in the non-clinical sample. (2) The additive/interactive hypothesis: If acceptance and cognitive restructuring are different but compatible forms of emotion regulation intervening at different points in the emotion generative process (e.g., Hofmann and Asmundson 2008 ), the effects of these different strategies may be expected to add or interact positively so that the subgroup of individuals who are high on both would score higher than those who are high on only one of these strategies. (3) The “acceptance-is-essential” hypothesis: If acceptance is an underlying functional dimension that is basic to all adaptive strategies of emotion regulation (Blackledge and Hayes 2001 ; Boulanger et al. 2010 ), subgroups who score generally high on acceptance should show the highest psychological well-being, regardless of their scores on cognitive restructuring.

Similarly, at the other end of the scale, we might expect to find one subgroup of individuals who score generally low on acceptance but not on cognitive restructuring, another subgroup of individuals who score generally low on cognitive restructuring but not on acceptance, and a third subgroup with low scores on both cognitive restructuring and acceptance. Again, alternative hypotheses may be contrasted: (1) The “no-strategies-is-worst” hypothesis : If both acceptance and cognitive change strategies are adaptive strategies, a subgroup with low scores on both of these strategies should be worst off in terms of psychological well-being. (2) The “acceptance-is-essential” hypothesis: If acceptance is an underlying functional dimension that is basic to all adaptive strategies of emotion regulation (Blackledge and Hayes 2001 ; Boulanger et al. 2010 ), individuals who score generally low on acceptance should be worst off, whether they score low on cognitive restructuring or not.

To summarize, the present research had two purposes. The first purpose was to test the hypothesis that the use of distractive strategies is adaptive when combined with acceptance, and maladaptive when combined with avoidance. The second purpose was to compare alternative hypotheses with regard to the how strategies related to cognitive restructuring and acceptance may be combined, as well as how different combinations relate to measures of psychological well-being. In order to test these hypotheses we used a person oriented approach to data analysis which means that we studied if it was possible to identify groups of individuals with similar profiles of scores across the studied variables and examine how these different groups scored on measures of psychological well-being.

Participants

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Non-Clinical Sample

A non-clinical sample of 1500 individuals (aged 18-70) was drawn randomly from the SPAR register (the Swedish government´ Person and Address Register), and were sent a letter with a questionnaire and a pre-stamped addressed return envelope. Of these, 638 individuals (364 women and 274 men, response rate 42 %) filled out the entire questionnaire and returned it. The letter also included information regarding the study as well as the measures. Participation was anonymous and no information was stored that could identify a specific participant. In addition to the measures to be used in the study, the participants were asked to state their gender, age and level of highest completed education.

Clinical Sample

Participants in the clinical sample ( N = 172) were volunteers recruited among patients currently in treatment in open psychiatric care in the county of Blekinge in Sweden. In total 350 booklets containing an information letter and all the measures were given to members of staff in open psychiatric care, who in turn administered them to clients they were in contact with. Of these 350 booklets, 172 were returned, rendering a response rate of 49 %. Of the respondents, 63 % were female and 37 % were male. There were no formal exclusionary criteria to participate in the study and we had no means of controlling who were asked to participate and who volunteered, nor their diagnosis and type of treatment. The population from which the sample was drawn (patients attending open psychiatric care in Blekinge during 2011) are known to have the following characteristics: 43 % are male, 57 % are female and the most common diagnostic groups are anxiety disorders (15 %), depressive disorders (14 %), schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders (13 %), personality disorders (9 %), bipolar disorder (7 %), neuropsychiatric disorders including mental retardations (7 %), substance abuse (5 %) and post-traumatic stress disorder (5 %).

Strategies of Emotion Regulation

To assess different types of strategies we used the participants’ scores on scales based on the factors identified in a previous study (Wolgast et al. 2012 ). There were three acceptance-related factors: Thought Avoidance (14 items), which refers to active efforts to avoid and suppress aversive cognitive material, Active Acceptance (7 items), which represents a combination of experiential acceptance and behavioral flexibility in the face of aversive emotions, and Resignation (4 items), which refers to passively accepting a situation or an aversive emotional state combined with an experience of not having the ability to do anything about it. There were also three factors related to Cognitive Restructuring: Cognitive Reappraisal (6 items), which refers to the traditional concept of reappraisal (i.e. changing emotional reactions by changing our appraisals of the emotion eliciting stimulus or situation), Distractive Refocusing (6 items), which represents strategies aimed at trying to think about something else, preferably something positive, entailing an unwillingness to remain in cognitive contact with the emotion eliciting stimulus or situation rather than to think differently about it, and finally Constructive Refocusing (12 items) , which refers to attempts to change not how we interpret the topography of the situation (i.e. how we interpret the factual characteristics of the events) but rather to reframe or reinterpret the function or consequence of the situation (e.g. what our behavioral options are given what has happened, what we can learn from the situation etc). All the scales showed adequate levels of internal consistency (Cronbach’s alphas: Thought Avoidance: .92, Active Acceptance: .75, Resignation: .73, Cognitive Reappraisal: .84, Distractive Refocusing: .79, Constructive Refocusing: .87).

Positive and Negative Affect Scale (PANAS)

To assess dispositional positive and negative emotionality participants completed the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS; Watson et al. 1988 ). The PANAS is a 20-item mood adjective checklist designed to measure the Positive Affect (PA) and Negative Affect (NA) factors and has shown satisfactory psychometric properties in previous research (Watson et al. 1988 ). To complete the PANAS, participants were instructed to use a five-point Likert scale (1, very slightly or not at all; 5, extremely) to indicate “to what extent you generally feel this way, that is, how you feel on the average” for each adjective. The Swedish version of the scale showed adequate internal consistency for both Positive Affect and Negative Affect (Cronbach’s alphas: Positive Affect = .89; Negative Affect = .92).

World Health Organization Quality of Life Assessment—Brief Version (WHOQOL-BREF)

Quality of life was assessed by the WHOQOL-BREF, developed and validated by WHO in several studies (Skevington et al. 2004 ). It contains 26 items, the response (from least to most) to each item being on a 5-point rating scale of a particular aspect of quality of life. Besides the first two items of general nature, the remaining 24 items of the instrument are known to factorise into four domains of quality of life, denoted by ‘physical health’ (7 items, domain 1), ‘psychological’ (6 items, domain 2), ‘social relationships’ (3 items, domain 3), and ‘environment’ (8 items, domain 4), respectively. The Swedish version of the scale used in the present study showed adequate internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = .87).

Hierarchical Cluster Analysis

The individual participants were grouped into clusters on the basis of their individual profiles of scores on the six scales related to acceptance and cognitive restructuring. This was done according to the LICUR procedure suggested by Bergman ( 1998 ) and using the statistical package for pattern-oriented analyses SLEIPNER 2.1 (Bergman and El-Khouri 2002 ). In a first step, the data were searched for multivariate outliers, which led to the identification and removal of one outlier. Secondly, clusters were formed using Ward’s hierarchical clustering method, which is a stepwise procedure that starts by considering each individual as a separate cluster and then merges the two clusters that results in the smallest increase in the overall error sum of squares in each subsequent step. In order to determine the optimal cluster solution we used the criteria suggested by Bergman ( 1998 ): (1) The cluster solution should be theoretically meaningful. (2) If a distinct reduction in the explained variance occurs when moving from one step to another, this may indicate that two not so similar clusters have been merged and that the resulting cluster solution is not optimal. (3) The number of clusters should not be expected to be less than five or to exceed fifteen. (4) The size of the explained variance for the chosen cluster solution should at the very least exceed 50 %, and preferably exceed 67 %. Additionally, the homogeneity coefficients of each cluster should preferably be <1.0. In a third step, a data simulation using Monte Carlo procedure with 20 re-samplings was performed to test if the explained variance for the identified cluster solution significantly exceeded what would be expected from a random data set with the same general properties as the “real” data set. In a final step, in order to improve the homogeneity of the clusters and to increase the proportion of explained variance, a non-hierarchical relocation procedure was performed (Bergman 1998 ), in which individuals were moved between clusters in order to find the optimal solution.

After removing an outlier identified by the residue procedure in SLEIPNER 2.1 (Bergman and El-Khouri 2002 ), 809 individuals were left for further analyses using Ward’s hierarchical clustering method. Applying the criteria suggested by Bergman ( 1998 ) resulted in the choice of a 9-cluster solution, which explained 59.9 % of the variance, whereas the 8 cluster solution would have resulted in a drop in explained variance to 57.1 %. The data simulation reliably showed that the explained variance for the chosen cluster solution was significantly higher than what would be expected by chance ( p < .01). After this, the relocation procedure was performed, resulting in a final nine cluster solution which explained 62.6 % of the variance and where all the clusters except one had homogeneity coefficients of <1.0 (cluster 5 had a homogeneity coefficient of 1.08).

First, descriptive data is presented on the two samples. Then the results of the cluster analysis are described, and the clusters are compared on positive and negative emotionality, life quality and clinical status. After that, the results are analyzed with regard to the research questions: First the hypothesis on distraction is tested. Second, the alternative hypotheses concerning the combination of a high use, and low use, of both acceptance and cognitive restructuring are compared.

Descriptive Data

Descriptive data on demographic and clinical variables for the clinical and non-clinical samples are presented in Table 1 . On the demographic variables, the samples differed significantly with regard to age, t (808) = 4.54, p < .01, and level of education, χ 2 (2) = 11.4, p < .01, but not with regard to gender, χ 2 (1) = 1.54, p = .21. With regard to positive and negative emotionality and quality of life, the differences between the samples were significant and large for all variables [PANAS-N: t (808) = 15.9, p < .01, d = 1.1; PANAS-P: t (808) = -17.1, p < .01, d = -1.2; Total WHOQOL: t (808) = 19.0, p < .01, d = 1.3]. The bivariate correlations between all self-report measures are presented in Table 2 .

Cluster Analysis

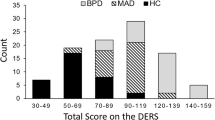

As stated above (see the section on hierarchical cluster analysis), the clustering procedure resulted in a nine cluster solution. Table 3 shows the means and standard deviations on each factor for each cluster as well for the whole group, whereas Fig. 1 displays the profile of z -scores (cluster mean minus total group mean, divided by the standard deviation of the total group) for each cluster on the 6 factors.

Pattern of z-scores across the 6 factors for all clusters. TA thought avoidance, R resignation, AA active acceptance, ConRef constructive refocusing, CogRe cognitive reappraisal, DR distractive refocusing

Comparisons Between the Clusters on Well-Being

A one-way ANOVA with the nine clusters as independent variable and age as dependent variable showed a significant omnibus effect [ F (8, 800) = 2.74, p < .01]. Tukey-corrected post-hoc comparisons showed that the only significant differences between the clusters were that Cluster 4 was older than Cluster 3 and Cluster 7. The gender distribution did not differ significantly across the nine clusters [ χ 2 (8) = 13.9, p = .09]. With regard to level of highest completed education, there was a significant omnibus effect, indicating that there were significant differences in the distribution across the clusters [ χ 2 (16) = 46.2, p < .01]. To further investigate this effect, the observed frequency in each cell was compared with the frequency expected if the educational level was randomly distributed across the clusters. The statistical testing was performed in accordance with the fixed-margins model using EXACON (Bergman and El-Khouri 1987 ). After adjusting the alpha level to allow for multiple comparisons using Bonferroni correction (critical α = .002; .05/27) the analysis showed that the only significant effect was that more participants in Cluster 2 had completed a university level education than what was to be expected by chance (observed frequency 54, expected frequency 34.2, χ 2 = 11.5, p = .0008).

Three Bonferroni corrected (critical α’s = .017) ANOVAs were performed with the nine clusters as independent variables and scores on PANAS-N, PANAS-P and WHOQOL as dependent variable in the separate analyses. To control for the observed differences between the clusters with regard to age and level of highest completed education, these variables were entered as covariates in the analyses. Means and standard deviations on the criterion variables for each cluster are presented, in descending order according to the mean score of the clusters, in Tables 3 , 4 and 5 (one table for each criterion variable). The omnibus tests showed that there were significant differences between the clusters on all three variables [PANAS-P: F (8, 798) = 85.1, p < .01, partial η 2 = .46; PANAS-N: F (8798) = 116.9, p < .01, partial η 2 = .54; WHOQOL: F (8, 798) = 110.7, p < .01, partial η 2 = .53]. Sidak-corrected post hoc comparisons were performed to examine the significance of the differences between the clusters on each dependent variable. The results from these analyses are presented in Tables 3 , 4 and 5 .

Representation of the Clusters in the Clinical and non-Clinical Samples

To study the over- and under-representation of each cluster in the clinical and non-clinical samples, the clusters were cross-tabulated with the two samples. Table 7 shows a comparison of the observed frequencies in each cell with the frequencies expected if the clusters had been randomly distributed across the samples. The statistical testing was performed in accordance with the fixed-margins model using EXACON (Bergman and El-Khouri 1987 ).

The Adaptiveness and Maladaptiveness of Distractive Refocusing

As seen in Table 3 and in Fig. 1 , two clusters showed high scores on Distractive Refocusing: cluster 3 and cluster 5. These two clusters had almost exactly the same score on Distractive Refocusing, but showed otherwise very different profiles. Whereas Cluster 3 combined high scores on Distractive Focusing with high scores on Thought Avoidance, Cluster 5 combined high scores on Distractive Refocusing with high scores on Active Acceptance. According to the hypothesis, Cluster 5 should show higher well-being than Cluster 3. This hypothesis was supported on all four variables: Cluster 5 scored significantly higher than Cluster 3 on positive emotionality (see Table 3 ), significantly lower on negative emotionality (see Table 4 ), and significantly higher on life quality (see Table 5 ). In addition, as seen in Table 6 , Cluster 5 was under-represented in the clinical sample (observed frequency: 11, expected frequency: 20, χ 2 = 4.0, p < .05), whereas Cluster 3 was over-represented in the clinical sample (observed frequency: 20, expected frequency: 13, χ 2 = 3.6, p < .05).

Combining High Use of Acceptance with High Use of Cognitive Restructuring

As seen in Fig. 1 , one of the clusters (Cluster 1) was characterized by consistently high scores on acceptance and consistently low scores on cognitive restructuring, and another (Cluster 2) by consistently high scores on both acceptance and cognitive restructuring. Interestingly, these two clusters showed a very similar profile on the acceptance factors, but differed widely on the cognitive restructuring factors. Still, as seen in Tables 4 , 5 , 6 and 7 , they did not differ significantly on any of the indicators of well-being. Interestingly, although both of these clusters were large (104 individuals in Cluster 1, and 108 individuals in Cluster 2), they were both completely unrepresented in the clinical sample – all 212 individuals were from the non-clinical sample. This speaks against the hypothesis that acceptance and cognitive restructuring have an additive or interactive effect on well-being. The results are, however, consistent with both of the other hypotheses – that is, the equifinality hypothesis (i.e., acceptance and cognitive change strategies achieve similar outcomes), and the “acceptance-is-essential hypothesis”. Unfortunately, the cluster analysis did not identify any cluster with consistently high scores on cognitive restructuring and consistently low scores on acceptance – if so, it would have been possible to contrast these two hypotheses.

Combining Low Use of Acceptance with Low Use of Cognitive Restructuring