Adapting and blending grounded theory with case study: a practical guide

- Published: 08 December 2023

- Volume 58 , pages 2979–3000, ( 2024 )

Cite this article

- Charles Dahwa ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7705-4627 1

951 Accesses

6 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

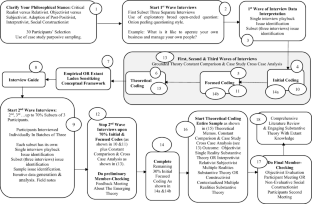

This article tackles how to adapt grounded theory by blending it with case study techniques. Grounded theory is commended for enabling qualitative researchers to avoid priori assumptions and intensely explore social phenomena leading to enhanced theorization and deepened contextualized understanding. However, it is criticized for generating enormous data that is difficult to manage, contentious treatment of literature review and category saturation. Further, while the proliferation of several versions of grounded theory brings new insights and some clarity, inevitably some bits of confusion also creep in, given the dearth of standard protocols applying across such versions. Consequently, the combined effect of all these challenges is that grounded theory is predominantly perceived as very daunting, costly and time consuming. This perception is discouraging many qualitative researchers from using grounded theory; yet using it immensely benefits qualitative research. To gradually impart grounded theory skills and to encourage its usage a key solution is to avoid a full-scale grounded theory but instead use its adapted version, which exploits case study techniques. How to do this is the research question for this article. Through a reflective account of my PhD research methodology the article generates new insights by providing an original and novel empirical account about how to adapt grounded theory blending it with case study techniques. Secondly, the article offers a Versatile Interview Cases Research Framework (VICaRF) that equips qualitative researchers with clear research questions and steps they can take to effectively adapt grounded theory by blending it with case study techniques.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Grounded Theory Methodology: Principles and Practices

Allwood, C.M.: The distinction between qualitative and quantitative research methods is problematic. Qual. Quant. 46 (5), 1417–1429 (2012)

Article Google Scholar

Andrade, A.D.: Interpretive research aiming at theory building: adopting and adapting the case study design. Qual. Rep. 14 (1), 42–60 (2009)

Google Scholar

Bruscaglioni, L.: Theorizing in grounded theory and creative abduction. Qual. Quant. 50 (5), 2009–2024 (2016)

Burrell, G., Morgan, G.: Sociological Paradigms and Organizational Analysis: Elements of the Sociology of Corporate Life. Heinemann, London (1979)

Chalmers, A.F.: What is This Thing Called Science? Open University Press, Maidenhead (1999)

Chamberlain, G.P.: Researching strategy formation process: an abductive methodology. Qual. Quant. 40 , 289–301 (2006)

Charmaz, K.: Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide Through Qualitative Research. Sage Publications Ltd, London (2006)

Charmaz, K.: Constructing Grounded Theory. SAGE, London (2014)

Cooke, F.L.: Concepts, contexts, and mindsets: putting human resource management research in perspectives. Hum. Resour. Manag. 28 (1), 1–13 (2017)

Cope, J.: Toward a dynamic learning perspective of entrepreneurship. Entrep. Theory Pract. 29 (4), 373–397 (2005)

Corbin, J., Strauss, A.: Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory, 4th edn. Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA (2015)

Creswell, J.W.: Qualitative Inquiry & research design: Choosing among five approaches, 3rd edn. Sage Publications Ltd., London (2013)

Dey, I.: Grounding Grounded Theory: Guidelines for Qualitative Inquiry. Academic, San Diego, CA (1999)

Diefenbach, T.: Are case studies more than sophisticated storytelling?: Methodological problems of qualitative empirical research mainly based on semi-structured interviews. Qual. Quant. 43 (6), 875–894 (2009)

Dunne, C.: The place of the literature review in grounded theory research. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 14 (2), 111–124 (2011)

Fairhurst, G.T., Putnam, L.L.: An integrative methodology for organizational oppositions: aligning grounded theory and discourse analysis. Organ. Res. Methods 22 (4), 917–940 (2019)

Francis, J.J., Johnston, M., Robertson, C., Glidewell, L., Entwistle, V., Eccles, M.P., Grimshaw, J.M.: What is an adequate sample size? Operationalising data saturation for theory-based interview studies. Psychol. Health 25 (10), 1229–1245 (2010)

Glaser, B.: Doing Grounded Theory: Issues and Discussions. Sociology Press, Mill Valley, CA (1998)

Glaser, B.G., Strauss, A.L.: The discovery of grounded theory: strategies for qualitative research. Aldine de Gruyter, Chicago, IL (1967)

Gordon, J.: The voice of the social worker: a narrative literature review. Br. J. Soc. Work. 48 (5), 1333–1350 (2018)

Hlady-Rispal, M., Jouison-Laffitte, E.: Qualitative research methods and epistemological frameworks: a review of publication trends in entrepreneurship. J. Small Bus. Manag. 52 (4), 594–614 (2014)

Iman, M.T., Boostani, D.: A qualitative investigation of the intersection of leisure and identity among high school students: application of grounded theory. Qual. Quant. 46 (2), 483–499 (2012)

Katz, J.A., Aldrich, H.E., Welbourne, T.M., Williams, P.M.: Guest editor’s comments special issue on human resource management and the SME: toward a new synthesis. Entrep. Theory Pract. 25 (1), 7–10 (2000)

Kibuku, R.N., Ochieng, D.O., Wausi, A.N.: Developing an e-learning theory for interaction and collaboration using grounded theory: a methodological approach. Qual. Rep. 26 (9), 0_1-2854 (2021)

Lai, Y., Saridakis, G., Johnstone, S.: Human resource practices, employee attitudes and small firm performance. Int. Small Bus. J. 35 (4), 470–494 (2017)

Lauckner, H., Paterson, M., Krupa, T.: Using constructivist case study methodology to understand community development processes: proposed methodological questions to guide the research process. Qual. Rep. 17 (13), 1–22 (2012)

Levers, M.J.D.: Philosophical paradigms, grounded theory, and perspectives on emergence, pp. 1–6. Sage Open, London (2013)

Marlow, S.: Human resource management in smaller firms: a contradiction in terms? Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 16 (4), 467–477 (2006)

Marlow, S., Taylor, S., Thompson, A.: Informality and formality in medium sized companies: contestation and synchronization. Br. J. Manag. 21 (4), 954–966 (2010)

Mason, M.: Sample size and saturation in PhD studies using qualitative interviews. Qual. Soc. Res. (2010). https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-11.3.1428

Mauceri, S.: Mixed strategies for improving data quality: the contribution of qualitative procedures to survey research. Qual. Quant. 48 , 2773–2790 (2014)

Mullen, M., Budeva, D.G., Doney, P.M.: Research methods in the leading small business entrepreneurship journals: a critical review with recommendations for future research. J. Small Bus. Manage. 47 (3), 287–307 (2009)

Niaz, M.: Can findings of qualitative research in education be generalized? Qual. Quant. 41 (3), 429–445 (2007)

Nolan, C.T., Garavan, T.N.: Human resource development in SMEs: a systematic review of the literature. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 18 (1), 85–107 (2016)

Onwuegbuzie, A.J., Leech, N.L.: A call for qualitative power analyses. Qual. Quant. 41 (1), 105–121 (2007)

Pentland, B.T.: Building process theory with narrative: from description to explanation. Acad. Manag. Rev. 24 (4), 711–724 (1999)

Popper, K.: The Logic of Scientific Discovery. Hutchinson, Tuebingen (1959)

Ramalho, R., Adams, P., Huggard, P., Hoare, K.: Literature review and constructivist grounded theory methodology. Qual. Soc. Res. J. 16 (3), 1–13 (2015)

Saunders, B., Sim, J., Kingstone, T., Baker, S., Waterfield, J., Bartlam, B., Burroughs, H., Jinks, C.: Saturation in qualitative research: exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Qual. Quant. 52 , 1893–1907 (2018)

Sharma, G., Kulshreshtha, K., Bajpai, N.: Getting over the issue of theoretical stagnation: an exploration and metamorphosis of grounded theory approach. Qual. Quant. 56 (2), 857–884 (2022)

Stake, R.E.: The Art of Case Study Research. Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA (1995)

Strauss, A.L., Corbin, J.: The Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. Sage, Newbury Park, CA (1998)

Thistoll, T., Hooper, V., Pauleen, D.J.: Acquiring and developing theoretical sensitivity through undertaking a grounded preliminary literature review. Qual. Quant. 50 (2), 619–636 (2016)

Tobi, H., Kampen, J.K.: Research design: the methodology for interdisciplinary research framework. Qual. Quant. 52 , 1209–1225 (2018)

Tomaszewski, L.E., Zarestky, J., Gonzalez, E.: Planning qualitative research: design and decision making for new researchers. Int J Qual Methods 19 , 1–7 (2020)

Tranfield, D., Denyer, D., Smart, P.: Towards a methodology for developing evidence informed management knowledge by means of systematic review. Br. J. Manag. 14 (3), 207–222 (2003)

Travers, G.: New methods, old problems: a sceptical view of innovation in qualitative research. Qual. Res. 9 (2), 161–179 (2009)

Tzagkarakis, S.I., Kritas, D.: Mixed research methods in political science and governance: approaches and applications. Qual. Quant. 57 , 1–15 (2022)

Urquhart, C.: Grounded Theory for Qualitative Research: A Practical Guide. Sage, London (2013)

Book Google Scholar

Vasileiou, K., Barnett, J., Thorpe, S., Young, T.: Characterising and justifying sample size sufficiency in interview-based studies: systematic analysis of qualitative health research over a 15-year period. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 18 (1), 1–18 (2018)

Welch, C., Piekkari, R., Plakoyiannaki, E., Mantymaki, E.P.: Theorising from case studies: towards a pluralist future for international business research. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 42 (5), 1–24 (2011)

Wiles, R., Crow, G., Pain, H.: Innovation in qualitative research methods: a narrative review. Qual. Res. 11 (5), 587–604 (2011)

Yin, R.K.: Case Study Research: Design and Methods. Sage, London (2014)

Download references

Acknowledgements

I am indebted to Professor Ben Lupton, my PhD Director of Studies and Dr Valerie Antcliff my second PhD supervisor, for their mentorship over the years. I continue to draw on the wealth of knowledge they invested in me to generate knowledge. My profound gratitude also goes to the chief editor, associate editor and reviewers for this journal whose insightful review strengthened this article.

This methodology was formulated and executed in a PhD that was fully funded by the Manchester Metropolitan University, UK.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Decent Work and Productivity Research Centre, Manchester Metropolitan University, All Saints Building, Manchester, M15 6BH, UK

Charles Dahwa

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

Dr CD is the sole author.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Charles Dahwa .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

This article has not been submitted to any other academic journals.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Dahwa, C. Adapting and blending grounded theory with case study: a practical guide. Qual Quant 58 , 2979–3000 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-023-01783-9

Download citation

Accepted : 27 October 2023

Published : 08 December 2023

Issue Date : June 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-023-01783-9

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Grounded theory

- Qualitative research

- Qualitative inquiry

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

10 Grounded Theory Examples (Qualitative Research Method)

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

Learn about our Editorial Process

Grounded theory is a qualitative research method that involves the construction of theory from data rather than testing theories through data (Birks & Mills, 2015).

In other words, a grounded theory analysis doesn’t start with a hypothesis or theoretical framework, but instead generates a theory during the data analysis process .

This method has garnered a notable amount of attention since its inception in the 1960s by Barney Glaser and Anselm Strauss (Corbin & Strauss, 2015).

Grounded Theory Definition and Overview

A central feature of grounded theory is the continuous interplay between data collection and analysis (Bringer, Johnston, & Brackenridge, 2016).

Grounded theorists start with the data, coding and considering each piece of collected information (for instance, behaviors collected during a psychological study).

As more information is collected, the researcher can reflect upon the data in an ongoing cycle where data informs an ever-growing and evolving theory (Mills, Bonner & Francis, 2017).

As such, the researcher isn’t tied to testing a hypothesis, but instead, can allow surprising and intriguing insights to emerge from the data itself.

Applications of grounded theory are widespread within the field of social sciences . The method has been utilized to provide insight into complex social phenomena such as nursing, education, and business management (Atkinson, 2015).

Grounded theory offers a sound methodology to unearth the complexities of social phenomena that aren’t well-understood in existing theories (McGhee, Marland & Atkinson, 2017).

While the methods of grounded theory can be labor-intensive and time-consuming, the rich, robust theories this approach produces make it a valuable tool in many researchers’ repertoires.

Real-Life Grounded Theory Examples

Title: A grounded theory analysis of older adults and information technology

Citation: Weatherall, J. W. A. (2000). A grounded theory analysis of older adults and information technology. Educational Gerontology , 26 (4), 371-386.

Description: This study employed a grounded theory approach to investigate older adults’ use of information technology (IT). Six participants from a senior senior were interviewed about their experiences and opinions regarding computer technology. Consistent with a grounded theory angle, there was no hypothesis to be tested. Rather, themes emerged out of the analysis process. From this, the findings revealed that the participants recognized the importance of IT in modern life, which motivated them to explore its potential. Positive attitudes towards IT were developed and reinforced through direct experience and personal ownership of technology.

Title: A taxonomy of dignity: a grounded theory study

Citation: Jacobson, N. (2009). A taxonomy of dignity: a grounded theory study. BMC International health and human rights , 9 (1), 1-9.

Description: This study aims to develop a taxonomy of dignity by letting the data create the taxonomic categories, rather than imposing the categories upon the analysis. The theory emerged from the textual and thematic analysis of 64 interviews conducted with individuals marginalized by health or social status , as well as those providing services to such populations and professionals working in health and human rights. This approach identified two main forms of dignity that emerged out of the data: “ human dignity ” and “social dignity”.

Title: A grounded theory of the development of noble youth purpose

Citation: Bronk, K. C. (2012). A grounded theory of the development of noble youth purpose. Journal of Adolescent Research , 27 (1), 78-109.

Description: This study explores the development of noble youth purpose over time using a grounded theory approach. Something notable about this study was that it returned to collect additional data two additional times, demonstrating how grounded theory can be an interactive process. The researchers conducted three waves of interviews with nine adolescents who demonstrated strong commitments to various noble purposes. The findings revealed that commitments grew slowly but steadily in response to positive feedback, with mentors and like-minded peers playing a crucial role in supporting noble purposes.

Title: A grounded theory of the flow experiences of Web users

Citation: Pace, S. (2004). A grounded theory of the flow experiences of Web users. International journal of human-computer studies , 60 (3), 327-363.

Description: This study attempted to understand the flow experiences of web users engaged in information-seeking activities, systematically gathering and analyzing data from semi-structured in-depth interviews with web users. By avoiding preconceptions and reviewing the literature only after the theory had emerged, the study aimed to develop a theory based on the data rather than testing preconceived ideas. The study identified key elements of flow experiences, such as the balance between challenges and skills, clear goals and feedback, concentration, a sense of control, a distorted sense of time, and the autotelic experience.

Title: Victimising of school bullying: a grounded theory

Citation: Thornberg, R., Halldin, K., Bolmsjö, N., & Petersson, A. (2013). Victimising of school bullying: A grounded theory. Research Papers in Education , 28 (3), 309-329.

Description: This study aimed to investigate the experiences of individuals who had been victims of school bullying and understand the effects of these experiences, using a grounded theory approach. Through iterative coding of interviews, the researchers identify themes from the data without a pre-conceived idea or hypothesis that they aim to test. The open-minded coding of the data led to the identification of a four-phase process in victimizing: initial attacks, double victimizing, bullying exit, and after-effects of bullying. The study highlighted the social processes involved in victimizing, including external victimizing through stigmatization and social exclusion, as well as internal victimizing through self-isolation, self-doubt, and lingering psychosocial issues.

Hypothetical Grounded Theory Examples

Suggested Title: “Understanding Interprofessional Collaboration in Emergency Medical Services”

Suggested Data Analysis Method: Coding and constant comparative analysis

How to Do It: This hypothetical study might begin with conducting in-depth interviews and field observations within several emergency medical teams to collect detailed narratives and behaviors. Multiple rounds of coding and categorizing would be carried out on this raw data, consistently comparing new information with existing categories. As the categories saturate, relationships among them would be identified, with these relationships forming the basis of a new theory bettering our understanding of collaboration in emergency settings. This iterative process of data collection, analysis, and theory development, continually refined based on fresh insights, upholds the essence of a grounded theory approach.

Suggested Title: “The Role of Social Media in Political Engagement Among Young Adults”

Suggested Data Analysis Method: Open, axial, and selective coding

Explanation: The study would start by collecting interaction data on various social media platforms, focusing on political discussions engaged in by young adults. Through open, axial, and selective coding, the data would be broken down, compared, and conceptualized. New insights and patterns would gradually form the basis of a theory explaining the role of social media in shaping political engagement, with continuous refinement informed by the gathered data. This process embodies the recursive essence of the grounded theory approach.

Suggested Title: “Transforming Workplace Cultures: An Exploration of Remote Work Trends”

Suggested Data Analysis Method: Constant comparative analysis

Explanation: The theoretical study could leverage survey data and in-depth interviews of employees and bosses engaging in remote work to understand the shifts in workplace culture. Coding and constant comparative analysis would enable the identification of core categories and relationships among them. Sustainability and resilience through remote ways of working would be emergent themes. This constant back-and-forth interplay between data collection, analysis, and theory formation aligns strongly with a grounded theory approach.

Suggested Title: “Persistence Amidst Challenges: A Grounded Theory Approach to Understanding Resilience in Urban Educators”

Suggested Data Analysis Method: Iterative Coding

How to Do It: This study would involve collecting data via interviews from educators in urban school systems. Through iterative coding, data would be constantly analyzed, compared, and categorized to derive meaningful theories about resilience. The researcher would constantly return to the data, refining the developing theory with every successive interaction. This procedure organically incorporates the grounded theory approach’s characteristic iterative nature.

Suggested Title: “Coping Strategies of Patients with Chronic Pain: A Grounded Theory Study”

Suggested Data Analysis Method: Line-by-line inductive coding

How to Do It: The study might initiate with in-depth interviews of patients who’ve experienced chronic pain. Line-by-line coding, followed by memoing, helps to immerse oneself in the data, utilizing a grounded theory approach to map out the relationships between categories and their properties. New rounds of interviews would supplement and refine the emergent theory further. The subsequent theory would then be a detailed, data-grounded exploration of how patients cope with chronic pain.

Grounded theory is an innovative way to gather qualitative data that can help introduce new thoughts, theories, and ideas into academic literature. While it has its strength in allowing the “data to do the talking”, it also has some key limitations – namely, often, it leads to results that have already been found in the academic literature. Studies that try to build upon current knowledge by testing new hypotheses are, in general, more laser-focused on ensuring we push current knowledge forward. Nevertheless, a grounded theory approach is very useful in many circumstances, revealing important new information that may not be generated through other approaches. So, overall, this methodology has great value for qualitative researchers, and can be extremely useful, especially when exploring specific case study projects . I also find it to synthesize well with action research projects .

Atkinson, P. (2015). Grounded theory and the constant comparative method: Valid qualitative research strategies for educators. Journal of Emerging Trends in Educational Research and Policy Studies, 6 (1), 83-86.

Birks, M., & Mills, J. (2015). Grounded theory: A practical guide . London: Sage.

Bringer, J. D., Johnston, L. H., & Brackenridge, C. H. (2016). Using computer-assisted qualitative data analysis software to develop a grounded theory project. Field Methods, 18 (3), 245-266.

Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (2015). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory . Sage publications.

McGhee, G., Marland, G. R., & Atkinson, J. (2017). Grounded theory research: Literature reviewing and reflexivity. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 29 (3), 654-663.

Mills, J., Bonner, A., & Francis, K. (2017). Adopting a Constructivist Approach to Grounded Theory: Implications for Research Design. International Journal of Nursing Practice, 13 (2), 81-89.

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 10 Reasons you’re Perpetually Single

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 20 Montessori Toddler Bedrooms (Design Inspiration)

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 21 Montessori Homeschool Setups

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 101 Hidden Talents Examples

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

- Privacy Policy

Home » Grounded Theory – Methods, Examples and Guide

Grounded Theory – Methods, Examples and Guide

Table of Contents

Grounded theory is a qualitative research method used to develop theories directly from data. Unlike other approaches that start with a hypothesis, grounded theory relies on systematic data collection and analysis to generate insights grounded in the data itself. This approach is particularly valuable for exploring new or under-researched areas, allowing researchers to develop theories based on observed patterns and relationships. This guide covers the core methods, examples, and steps for conducting grounded theory research.

Grounded Theory

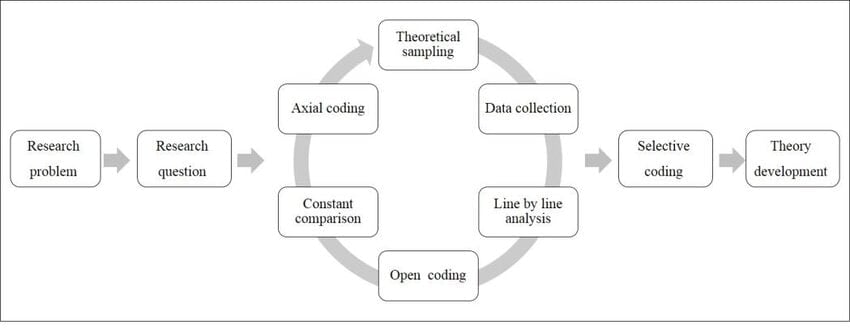

Grounded theory was introduced by sociologists Barney Glaser and Anselm Strauss in the 1960s as a way to build theory systematically from the ground up. Grounded theory starts with data collection and employs an iterative process, where data is continuously coded, analyzed, and compared. This method generates concepts and patterns directly from the data, leading to theories that reflect the real-world experiences of participants.

Key Features of Grounded Theory :

- Theory Generation : The aim is to develop a theory rather than test an existing hypothesis.

- Constant Comparison : Data is analyzed in a continuous, comparative manner.

- Iterative Process : Data collection, coding, and analysis occur simultaneously.

- Theoretical Sampling : Sampling decisions are based on emerging patterns in the data.

Methods in Grounded Theory

- Data Collection Grounded theory typically uses in-depth interviews, observations, and open-ended questionnaires to gather rich, qualitative data. Data is often collected from a relatively small sample to enable detailed analysis.

- Open Coding Open coding is the first stage of analysis, where data is broken down into distinct parts, and codes are assigned to label important concepts. During this phase, researchers identify initial categories and themes by segmenting data into meaningful units. Example : In a study on patient experiences in healthcare, open coding might include labels like “waiting times,” “communication,” and “empathy.”

- Axial Coding Axial coding follows open coding and involves identifying relationships among the initial codes. Researchers connect categories to form more complex ideas, such as linking “communication” with “patient satisfaction.” Example : “Communication” may be linked to both “patient satisfaction” and “trust in healthcare providers,” revealing an interconnected framework.

- Selective Coding Selective coding focuses on identifying a central category that represents the main theme of the research. This central concept serves as the foundation for developing the final theory, integrating and refining previous codes. Example : In a study on job satisfaction, the core concept might be “work-life balance,” with other themes like “workload,” “support from colleagues,” and “flexible hours” linked to it.

- Theoretical Sampling Theoretical sampling is used to gather more data specifically on emerging categories. This step is essential to refining and validating the developing theory and ensures that data is gathered based on the emerging concepts rather than a pre-determined sampling plan.

- Memo-Writing Memo-writing involves recording insights, interpretations, and connections that emerge during data analysis. Memos serve as a researcher’s notes, helping to develop the emerging theory and clarify ideas.

- Theory Development The final stage is synthesizing the codes, categories, and relationships into a cohesive theory. This theory should offer a clear explanation or model based on the data patterns and insights.

Steps for Conducting Grounded Theory Research

Step 1: identify the research area.

Begin by identifying a general area of interest or an under-researched topic that requires exploration. Grounded theory is well-suited to studies without a pre-existing framework, focusing on participants’ lived experiences.

Example : Exploring how remote work impacts employee well-being and productivity.

Step 2: Collect Initial Data

Use interviews, observations, or open-ended surveys to gather initial data. The questions should be broad and open-ended to encourage participants to share their experiences in detail.

Example : Ask remote employees, “What are the biggest challenges and benefits of working from home?”

Step 3: Open Coding

Break down the data into codes, labeling significant phrases, actions, or ideas. Look for recurring words, phrases, or themes that provide insight into participants’ perspectives.

Example : Codes like “isolation,” “work-life balance,” and “communication issues” might emerge in the initial coding phase.

Step 4: Axial Coding

Organize and connect codes to identify broader categories and relationships. Consider how different codes relate to one another to form a cohesive understanding.

Example : Codes related to “work-life balance” and “time management” might be grouped under a larger category, such as “work-life challenges in remote work.”

Step 5: Theoretical Sampling

Based on the emerging categories, collect additional data to further explore or validate certain aspects of the study. Sampling is driven by the need to refine categories or clarify relationships.

Example : Interview additional remote workers specifically about their strategies for managing isolation, based on initial findings.

Step 6: Selective Coding

Identify the main category that encapsulates the primary focus of the study. Develop a theory that explains the relationships among categories and offers insights into the research question.

Example : “Remote work autonomy” could be the central category, with subcategories like “flexibility,” “challenges of isolation,” and “productivity management” contributing to the overall theory.

Step 7: Memo-Writing and Theory Development

Continue writing memos to capture reflections, connections, and theoretical insights. Use these notes to build a comprehensive theory that answers the research question.

Example : The emerging theory might suggest that remote work autonomy enhances job satisfaction but also increases the need for social support to prevent isolation.

Examples of Grounded Theory Research

- Topic : How patients cope with chronic illness.

- Methods : Interviews with patients dealing with chronic health issues, focusing on how they manage daily life.

- Findings : Theory on coping mechanisms categorizes patient strategies into “support networks,” “self-care routines,” and “mindset adjustments.”

- Topic : Teacher adaptation to remote learning.

- Methods : Observations and interviews with teachers on their experiences with online teaching.

- Findings : Theory on adaptation reveals themes like “technology proficiency,” “student engagement challenges,” and “resource limitations.”

- Topic : Factors influencing entrepreneurial success.

- Methods : Interviews with entrepreneurs across industries.

- Findings : Emerging theory identifies categories such as “resilience,” “networking,” “market knowledge,” and “financial planning” as key success factors.

Advantages and Limitations of Grounded Theory

Advantages :

- Flexible and Adaptable : Grounded theory is highly adaptable and allows researchers to follow emerging themes, making it suitable for exploring new or complex areas.

- Data-Driven : Theories developed are grounded in real data, enhancing their relevance and applicability.

- Useful for Theory Building : This method provides a structured way to develop theories directly from data, which can be valuable for areas with limited pre-existing theories.

Limitations :

- Time-Consuming : Grounded theory requires continuous data collection and analysis, which can be lengthy.

- Requires Analytical Skill : Coding and developing theory require skillful interpretation, which can be challenging for new researchers.

- Subjectivity : The researcher’s interpretation plays a significant role, which may introduce bias if not managed carefully.

Tips for Writing a Grounded Theory Research Paper

- Introduce Grounded Theory : Briefly explain grounded theory and why it’s suitable for the study.

- Describe Data Collection and Coding : Provide a clear description of the data collection, coding, and categorization methods.

- Include Examples of Codes and Categories : Use examples of codes and categories to demonstrate the analytical process.

- Explain Theory Development : Describe how the theory emerged from data, supported by specific examples from your analysis.

- Discuss Theoretical Implications : Highlight the broader implications of the theory for research, practice, or policy.

Grounded theory is a powerful qualitative research method that builds theory directly from data, making it invaluable for studying complex, unexplored, or evolving areas. By following methods like open, axial, and selective coding, researchers can develop theories that reflect the lived experiences and insights of participants. Although demanding, grounded theory provides a structured approach to discovering new knowledge and has far-reaching applications across disciplines.

- Charmaz, K. (2014). Constructing Grounded Theory . Sage Publications.

- Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research . Aldine.

- Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (2015). Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory . Sage Publications.

- Birks, M., & Mills, J. (2015). Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide . Sage Publications.

- Bryant, A., & Charmaz, K. (2007). The Sage Handbook of Grounded Theory . Sage Publications.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Graphical Methods – Types, Examples and Guide

Critical Analysis – Types, Examples and Writing...

Narrative Analysis – Types, Methods and Examples

Phenomenology – Methods, Examples and Guide

Bimodal Histogram – Definition, Examples

Correlation Analysis – Types, Methods and...

Grounded Theory In Qualitative Research: A Practical Guide

Saul McLeod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul McLeod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

Grounded theory is a useful approach when you want to develop a new theory based on real-world data Instead of starting with a pre-existing theory, grounded theory lets the data guide the development of your theory.

What Is Grounded Theory?

Grounded theory is a qualitative method specifically designed to inductively generate theory from data. It was developed by Glaser and Strauss in 1967.

- Data shapes the theory: Instead of trying to prove an existing theory, you let the data guide your findings.

- No guessing games: You don’t start with assumptions or try to confirm your own biases.

- Data collection and analysis happen together: You analyze information as you gather it, which helps you decide what data to collect next.

It is important to note that grounded theory is an inductive approach where a theory is developed from collected real-world data rather than trying to prove or disprove a hypothesis like in a deductive scientific approach

You gather information, look for patterns, and use those patterns to develop an explanation.

It is a way to understand why people do things and how those actions create patterns. Imagine you’re trying to figure out why your friends love a certain video game.

Instead of asking an adult, you observe your friends while they’re playing, listen to them talk about it, and maybe even play a little yourself. By studying their actions and words, you’re using grounded theory to build an understanding of their behavior.

This qualitative method of research focuses on real-life experiences and observations, letting theories emerge naturally from the data collected, like piecing together a puzzle without knowing the final image.

When should you use grounded theory?

Grounded theory research is useful for beginning researchers, particularly graduate students, because it offers a clear and flexible framework for conducting a study on a new topic.

Grounded theory works best when existing theories are either insufficient or nonexistent for the topic at hand.

Since grounded theory is a continuously evolving process, researchers collect and analyze data until theoretical saturation is reached or no new insights can be gained.

What is the final product of a GT study?

The final product of a grounded theory (GT) study is an integrated and comprehensive grounded theory that explains a process or scheme associated with a phenomenon.

The quality of a GT study is judged on whether it produces this middle-range theory

Middle-range theories are sort of like explanations that focus on a specific part of society or a particular event. They don’t try to explain everything in the world. Instead, they zero in on things happening in certain groups, cultures, or situations.

Think of it like this: a grand theory is like trying to understand all of weather at once, but a middle-range theory is like focusing on how hurricanes form.

Here are a few examples of what middle-range theories might try to explain:

- How people deal with feeling anxious in social situations.

- How people act and interact at work.

- How teachers handle students who are misbehaving in class.

Core Components of Grounded Theory

This terminology reflects the iterative, inductive, and comparative nature of grounded theory, which distinguishes it from other research approaches.

- Theoretical Sampling : The researcher uses theoretical sampling to choose new participants or data sources based on the emerging findings of their study. The goal is to gather data that will help to further develop and refine the emerging categories and theoretical concepts.

- Theoretical Sensitivity: Researchers need to be aware of their preconceptions going into a study and understand how those preconceptions could influence the research. However, it is not possible to completely separate a researcher’s history and experience from the construction of a theory.

- Coding : Coding is the process of analyzing qualitative data (usually text) by assigning labels (codes) to chunks of data that capture their essence or meaning. It allows you to condense, organize and interpret your data.

- Core Category: The core category encapsulates and explains the grounded theory as a whole. Researchers identify a core category to focus on during the later stages of their research.

- Memos : Researchers use memos to record their thoughts and ideas about the data, explore relationships between codes and categories, and document the development of the emerging grounded theory. Memos support the development of theory by tracking emerging themes and patterns.

- Theoretical Saturation : This term refers to the point in a grounded theory study when collecting additional data does not yield any new theoretical insights. The researcher continues the process of collecting and analyzing data until theoretical saturation is reached.

- Constant Comparative Analysis: This method involves the systematic comparison of data points, codes, and categories as they emerge from the research process. Researchers use constant comparison to identify patterns and connections in their data.

Barney Glaser and Anselm Strauss first introduced grounded theory in 1967 in their book, The Discovery of Grounded Theory .

Their aim was to create a research method that prioritized real-world data to understand social behavior.

However, their approaches diverged over time, leading to two distinct versions: Glaserian and Straussian grounded theory.

The different versions of grounded theory diverge in their approaches to coding , theory construction, and the use of literature.

All versions of grounded theory share the goal of generating a middle-range theory that explains a social process or phenomenon.

They also emphasize the importance of theoretical sampling , constant comparative analysis , and theoretical saturation in developing a robust theory

Glaserian Grounded Theory

Glaserian grounded theory emphasizes the emergence of theory from data and discourages the use of pre-existing literature.

Glaser believed that adopting a specific philosophical or disciplinary perspective reduces the broader potential of grounded theory.

For Glaser, prior understandings should be based on the general problem area and reading very wide to alert or sensitize one to a wide range of possibilities.

It prioritizes parsimony , scope , and modifiability in the resulting theory

Straussian Grounded Theory

Strauss and Corbin (1990) focused on developing the analytic techniques and providing guidance to novice researchers.

Straussian grounded theory utilizes a more structured approach to coding and analysis and acknowledges the role of the literature in shaping research.

It acknowledges the role of deduction and validation in addition to induction.

Strauss and Corbin also emphasize the use of unstructured interview questions to encourage participants to speak freely

Critics of this approach believe it produced a rigidity never intended for grounded theory.

Constructivist Grounded Theory

This version, primarily associated with Charmaz, recognizes that knowledge is situated, partial, provisional, and socially constructed. It emphasizes abstract and conceptual understandings rather than explanations.

Kathy Charmaz expanded on original versions of GT, emphasizing the researcher’s role in interpreting findings

Constructivist grounded theory acknowledges the researcher’s influence on the research process and the co-creation of knowledge with participants

Situational Analysis

Developed by Clarke, this version builds upon Straussian and Constructivist grounded theory and incorporates postmodern , poststructuralist , and posthumanist perspectives.

Situational analysis incorporates postmodern perspectives and considers the role of nonhuman actors

It introduces the method of mapping to analyze complex situations and emphasizes both human and nonhuman elements .

- Discover New Insights: Grounded theory lets you uncover new theories based on what your data reveals, not just on pre-existing ideas.

- Data-Driven Results: Your conclusions are firmly rooted in the data you’ve gathered, ensuring they reflect reality. This close relationship between data and findings is a key factor in establishing trustworthiness.

- Avoids Bias: Because gathering data and analyzing it are closely intertwined, researchers are truly observing what emerges from data, and are less likely to let their preconceptions color the findings.

- Streamlined data gathering and analysis: Analyzing and collecting data go hand in hand. Data is collected, analyzed, and as you gain insight from analysis, you continue gathering more data.

- Synthesize Findings : By applying grounded theory to a qualitative metasynthesis , researchers can move beyond a simple aggregation of findings and generate a higher-level understanding of the phenomena being studied.

Limitations

- Time-Consuming: Analyzing qualitative data can be like searching for a needle in a haystack; it requires careful examination and can be quite time-consuming, especially without software assistance6.

- Potential for Bias: Despite safeguards, researchers may unintentionally influence their analysis due to personal experiences.

- Data Quality: The success of grounded theory hinges on complete and accurate data; poor quality can lead to faulty conclusions.

Practical Steps

Grounded theory can be conducted by individual researchers or research teams. If working in a team, it’s important to communicate regularly and ensure everyone is using the same coding system.

Grounded theory research is typically an iterative process. This means that researchers may move back and forth between these steps as they collect and analyze data.

Instead of doing everything in order, you repeat the steps over and over.

This cycle keeps going, which is why grounded theory is called a circular process.

Continue to gather and analyze data until no new insights or properties related to your categories emerge. This saturation point signals that the theory is comprehensive and well-substantiated by the data.

Theoretical sampling, collecting sufficient and rich data, and theoretical saturation help the grounded theorist to avoid a lack of “groundedness,” incomplete findings, and “premature closure.

1. Planning and Philosophical Considerations

Begin by considering the phenomenon you want to study and assess the current knowledge surrounding it.

However, refrain from detailing the specific aspects you seek to uncover about the phenomenon to prevent pre-existing assumptions from skewing the research.

- Discern a personal philosophical position. Before beginning a research study, it is important to consider your philosophical stance and how you view the world, including the nature of reality and the relationship between the researcher and the participant. This will inform the methodological choices made throughout the study.

- Investigate methodological possibilities. Explore different research methods that align with both the philosophical stance and research goals of the study.

- Plan the study. Determine the research question, how to collect data, and from whom to collect data.

- Conduct a literature review. The literature review is an ongoing process throughout the study. It is important to avoid duplicating existing research and to consider previous studies, concepts, and interpretations that relate to the emerging codes and categories in the developing grounded theory.

2. Recruit participants using theoretical sampling

Initially, select participants who are readily available ( convenience sampling ) or those recommended by existing participants ( snowball sampling ).

As the analysis progresses, transition to theoretical sampling , involving the deliberate selection of participants and data sources to refine your emerging theory.

This method is used to refine and develop a grounded theory. The researcher uses theoretical sampling to choose new participants or data sources based on the emerging findings of their study.

This could mean recruiting participants who can shed light on gaps in your understanding uncovered during the initial data analysis.

Theoretical sampling guides further data collection by identifying participants or data sources that can provide insights into gaps in the emerging theory

The goal is to gather data that will help to further develop and refine the emerging categories and theoretical concepts.

Theoretical sampling starts early in a GT study and generally requires the researcher to make amendments to their ethics approvals to accommodate new participant groups.

3. Collect Data

The researcher might use interviews, focus groups, observations, or a combination of methods to collect qualitative data.

- Observations : Watching and recording phenomena as they occur. Can be participant (researcher actively involved) or non-participant (researcher tries not to influence behaviors), and covert (participants unaware) or overt (participants aware).

- Interviews : One-on-one conversations to understand participants’ experiences. Can be structured (predetermined questions), informal (casual conversations), or semi-structured (flexible structure to explore emerging issues).

- Focus groups : Dynamic discussions with 4-10 participants sharing characteristics, moderated by the researcher using a topic guide.

- Ethnography : Studying a group’s behaviors and social interactions in their environment through observations, field notes, and interviews. Researchers immerse themselves in the community or organization for an in-depth understanding.

4. Begin open coding as soon as data collection starts

Open coding is the first stage of coding in grounded theory, where you carefully examine and label segments of your data to identify initial concepts and ideas.

This process involves scrutinizing the data and creating codes grounded in the data itself.

The initial codes stay close to the data, aiming to capture and summarize critically and analytically what is happening in the data

To begin open coding, read through your data, such as interview transcripts, to gain a comprehensive understanding of what is being conveyed.

As you encounter segments of data that represent a distinct idea, concept, or action, you assign a code to that segment. These codes act as descriptive labels summarizing the meaning of the data segment.

For instance, if you were analyzing interview data about experiences with a new medication, a segment of data might describe a participant’s difficulty sleeping after taking the medication. This segment could be labeled with the code “trouble sleeping”

Open coding is a crucial step in grounded theory because it allows you to break down the data into manageable units and begin to see patterns and themes emerge.

As you continue coding, you constantly compare different segments of data to refine your understanding of existing codes and identify new ones.

For instance, excerpts describing difficulties with sleep might be grouped under the code “trouble sleeping”.

This iterative process of comparing data and refining codes helps ensure the codes accurately reflect the data.

Open coding is about staying close to the data, using in vivo terms or gerunds to maintain a sense of action and process

5. Reflect on thoughts and contradictions by writing grounded theory memos during analysis

During open coding, it’s crucial to engage in memo writing. Memos serve as your “notes to self”, allowing you to reflect on the coding process, note emerging patterns, and ask analytical questions about the data.

Document your thoughts, questions, and insights in memos throughout the research process.

These memos serve multiple purposes: tracing your thought process, promoting reflexivity (self-reflection), facilitating collaboration if working in a team, and supporting theory development.

Early memos tend to be shorter and less conceptual, often serving as “preparatory” notes. Later memos become more analytical and conceptual as the research progresses.

Memo Writing

- Reflexivity and Recognizing Assumptions: Researchers should acknowledge the influence of their own experiences and assumptions on the research process. Articulating these assumptions, perhaps through memos, can enhance the transparency and trustworthiness of the study.

- Write memos throughout the research process. Memo writing should occur throughout the entire research process, beginning with initial coding.67 Memos help make sense of the data and transition between coding phases.8

- Ask analytic questions in early memos. Memos should include questions, reflections, and notes to explore in subsequent data collection and analysis.8

- Refine memos throughout the process. Early memos will be shorter and less conceptual, but will become longer and more developed in later stages of the research process.7 Later memos should begin to develop provisional categories.

6. Group codes into categories using axial coding

Axial coding is the process of identifying connections between codes, grouping them together into categories to reveal relationships within the data.

Axial coding seeks to find the axes that connect various codes together.

For example, in research on school bullying, focused codes such as “Doubting oneself, getting low self-confidence, starting to agree with bullies” and “Getting lower self-confidence; blaming oneself” could be grouped together into a broader category representing the impact of bullying on self-perception.

Similarly, codes such as “Being left by friends” and “Avoiding school; feeling lonely and isolated” could be grouped into a category related to the social consequences of bullying.

These categories then become part of the emerging grounded theory, explaining the multifaceted aspects of the phenomenon.

Qualitative data analysis software often represents these categories as nested codes, visually demonstrating the hierarchy and interconnectedness of the concepts.

This hierarchical structure helps researchers organize their data, identify patterns, and develop a more nuanced understanding of the relationships between different aspects of the phenomenon being studied.

This process of axial coding is crucial for moving beyond descriptive accounts of the data towards a more theoretically rich and explanatory grounded theory.

7. Define the core category using selective coding

During selective coding , the final development stage of grounded theory analysis, a researcher focuses on developing a detailed and integrated theory by selecting a core category and connecting it to other categories developed during earlier coding stages.

The core category is the central concept that links together the various categories and subcategories identified in the data and forms the foundation of the emergent grounded theory.

This core category will encapsulate the main theme of your grounded theory, that encompasses and elucidates the overarching process or phenomenon under investigation.

This phase involves a concentrated effort to refine and integrate categories, ensuring they align with the core category and contribute to the overall explanatory power of the theory.

The theory should comprehensively describe the process or scheme related to the phenomenon being studied.

For example, in a study on school bullying, if the core category is “victimization journey,” the researcher would selectively code data related to different stages of this journey, the factors contributing to each stage, and the consequences of experiencing these stages.

This might involve analyzing how victims initially attribute blame, their coping mechanisms, and the long-term impact of bullying on their self-perception.

Continue collecting data and analyzing until you reach theoretical saturation

Selective coding focuses on developing and saturating this core category, leading to a cohesive and integrated theory.

Through selective coding, researchers aim to achieve theoretical saturation, meaning no new properties or insights emerge from further data analysis.

This signifies that the core category and its related categories are well-defined, and the connections between them are thoroughly explored.

This rigorous process strengthens the trustworthiness of the findings by ensuring the theory is comprehensive and grounded in a rich dataset.

It’s important to note that while a grounded theory seeks to provide a comprehensive explanation, it remains grounded in the data.

The theory’s scope is limited to the specific phenomenon and context studied, and the researcher acknowledges that new data or perspectives might lead to modifications or refinements of the theory

- Constant Comparative Analysis: This method involves the systematic comparison of data points, codes, and categories as they emerge from the research process. Researchers use constant comparison to identify patterns and connections in their data. There are different methods for comparing excerpts from interviews, for example, a researcher can compare excerpts from the same person, or excerpts from different people. This process is ongoing and iterative, and it continues until the researcher has developed a comprehensive and well-supported grounded theory.

- Continue until reaching theoretical saturation : Continue to gather and analyze data until no new insights or properties related to your categories. This saturation point signals that the theory is comprehensive and well-substantiated by the data.

8. Theoretical coding and model development

Theoretical coding is a process in grounded theory where researchers use advanced abstractions, often from existing theories, to explain the relationships found in their data.

Theoretical coding often occurs later in the research process and involves using existing theories to explain the connections between codes and categories.

This process helps to strengthen the explanatory power of the grounded theory. Theoretical coding should not be confused with simply describing the data; instead, it aims to explain the phenomenon being studied, distinguishing grounded theory from purely descriptive research.

Using the developed codes, categories, and core category, create a model illustrating the process or phenomenon.

Here is some advice for novice researchers on how to apply theoretical coding:

- Begin with data analysis: Don’t start with a pre-determined theory. Instead, allow the theory to emerge from your data through careful analysis and coding.

- Use existing theories as a guide: While the theory should primarily emerge from your data, you can use existing theories from any discipline to help explain the connections you are seeing between your categories. This demonstrates how your research builds on established knowledge.

- Use Glaser’s coding families: Consider applying Glaser’s (1978) coding families in the later stages of analysis as a simple way to begin theoretical coding. Remember that your analysis should guide which theoretical codes are most appropriate.

- Keep it simple: Theoretical coding doesn’t need to be overly complex. Focus on finding an existing theory that effectively explains the relationships you have identified in your data.

- Be transparent: Clearly articulate the existing theory you are using and how it explains the connections between your categories.

- Theoretical coding is an iterative process : Remain open to revising your chosen theoretical codes as your analysis deepens and your grounded theory evolves.

9. Write your grounded theory

Present your findings in a clear and accessible manner, ensuring the theory is rooted in the data and explains the relationships between the identified concepts and categories.

The end product of this process is a well-defined, integrated grounded theory that explains a process or scheme related to the phenomenon studied.

- Develop a dissemination plan : Determine how to share the research findings with others.

- Evaluate and implement : Reflect on the research process and quality of findings, then share findings with relevant audiences in service of making a difference in the world

Reading List

Grounded Theory Review : This is an international journal that publishes articles on grounded theory.

- Birks, M., & Mills, J. (2015). Grounded theory: A practical guide . Sage.

- Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (1990). Grounded theory research: Procedures, canons, and evaluative criteria. Qualitative Sociology, 13, 3-21.

- Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing Grounded Theory: A practical guide through Qualitative Analysis. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage.

- Clarke, A. E. (2003). Situational analyses: Grounded theory mapping after the postmodern turn . Symbolic interaction , 26 (4), 553-576.

- Glaser, B. G. (1978). Theoretical sensitivity . University of California.

- Glaser, B. G. (2005). The grounded theory perspective III: Theoretical coding . Sociology Press.

- Glaser, B. G., & Holton, J. (2004, May). Remodeling grounded theory. In Forum qualitative sozialforschung/forum: qualitative social research (Vol. 5, No. 2).

- Charmaz, K. (2012). The power and potential of grounded theory. Medical sociology online , 6 (3), 2-15.

- Glaser, B., & Strauss, A. (1965). Awareness of dying. New Brunswick. NJ: Aldine. This was the first published grounded theory study

- Glaser, B., & Strauss, A. (2017). Discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research . Routledge.

- Pidgeon, N., & Henwood, K. (1997). Using grounded theory in psychological research. In N. Hayes (Ed.), Doing qualitative analysis in psychology Press/Erlbaum (UK) Taylor & Francis.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Grounded theory was first introduced more than 50 years ago, but researchers are often still uncertain about how to implement it. This is not surprising, considering that even the two pioneers of this qualitative design, Glaser and Strauss, have different views about its approach, and these are just two of multiple variations found in the literature.

Abstract: The grounded theory and case study all have one thing in common the general process of research that begins with a research problem and proceeds to the questions, the data collection, the data analysis and ... Furthermore Yin, (2003) define case method is a research design that is often guided by a framework

This article tackles how to adapt grounded theory by blending it with case study techniques. Grounded theory is commended for enabling qualitative researchers to avoid priori assumptions and intensely explore social phenomena leading to enhanced theorization and deepened contextualized understanding. However, it is criticized for generating enormous data that is difficult to manage ...

raphy, more interviews in grounded theory) and extent of data collection (e.g., only interviews in phenomenology, multiple forms in case study research to provide the in-depth case picture). At the data analysis stage, the differences are most pronounced. Not only is the distinction one of specificity of the analysis phase (e.g., grounded the-

The aim of all research is to advance, refine and expand a body of knowledge, establish facts and/or reach new conclusions using systematic inquiry and disciplined methods. 1 The research design is the plan or strategy researchers use to answer the research question, which is underpinned by philosophy, methodology and methods. 2 Birks 3 defines philosophy as 'a view of the world encompassing ...

Title: A taxonomy of dignity: a grounded theory study Citation: Jacobson, N. (2009).A taxonomy of dignity: a grounded theory study. BMC International health and human rights, 9(1), 1-9.. Description: This study aims to develop a taxonomy of dignity by letting the data create the taxonomic categories, rather than imposing the categories upon the analysis.

can draw predominantly from case study design (Merriam, 1998; Stake, 2006; Yin, 2003) and constructivist grounded theory approach to data analysis (Charmaz, 2006). Merriam (1998) notes, "A case study design is employed to gain an in-depth understanding of the situation and meaning for those involved" (p. 19).

Grounded theory is a powerful qualitative research method that builds theory directly from data, making it invaluable for studying complex, unexplored, or evolving areas. By following methods like open, axial, and selective coding, researchers can develop theories that reflect the lived experiences and insights of participants.

Since grounded theory is a continuously evolving process, researchers collect and analyze data until theoretical saturation is reached or no new insights can be gained. What is the final product of a GT study? The final product of a grounded theory (GT) study is an integrated and comprehensive grounded theory that explains a process or scheme ...

phenomenology, grounded theory, ethnography, and case studies. For each approach, I pose a definition, briefly trace its history, explore types of stud- ... 54—— Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design 04-Creswell2e.qxd 11/28/2006 3:39 PM Page 54. emphasize the second form in his writings. More recently, Chase (2005)