Advertisement

Cervical cancer in Ethiopia: a review of the literature

- Review article

- Published: 15 October 2022

- Volume 34 , pages 1–11, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

- Awoke Derbie ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6949-3494 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 ,

- Daniel Mekonnen 1 , 3 ,

- Endalkachew Nibret 5 ,

- Eyaya Misgan 6 ,

- Melanie Maier 7 ,

- Yimtubezinash Woldeamanuel 2 , 4 &

- Tamrat Abebe 4

2286 Accesses

11 Citations

1 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Cervical cancer is one of the most common malignancies affecting women worldwide with large geographic variations in prevalence and mortality rates. It is one of the leading causes of cancer-related deaths in Ethiopia, where vaccination and screening are less implemented. However, there is a scarcity of literature in the field. Therefore, the objective of this review was to describe current developments in cervical cancer in the Ethiopian context. The main topics presented were the burden of cervical cancer, knowledge of women about the disease, the genotype distribution of Human papillomavirus (HPV), vaccination, and screening practices in Ethiopia.

Published literature in the English language on the above topics until May 2021 were retrieved from PubMed/Medline, SCOPUS, Google Scholar, and the Google database using relevant searching terms. Combinations of the following terms were considered to retrieve literature; < Cervical cancer, uterine cervical neoplasms, papillomavirus infections, papillomavirus vaccines, knowledge about cervical cancer, genotype distribution of HPV and Ethiopia > . The main findings were described thematically.

Cervical cancer is the second most common and the second most deadly cancer in Ethiopia, The incidence and prevalence of the disease is increasing from time to time because of the growth and aging of the population, as well as an increasing prevalence of well-established risk factors. Knowledge and awareness about cervical cancer is quite poor among Ethiopian women. According to a recent report (2021), the prevalence of previous screening practices among Ethiopian women was at 14%. Although HPV 16 is constantly reported as the common genotype identified from different grade cervical lesions in Ethiopia, studies reported different HPV genotype distributions across the country. According to a recent finding, the most common HPV types identified from cervical lesions in the country were HPV-16, HPV-52, HPV-35, HPV-18, and HPV-56. Ethiopia started vaccinating school girls using Gardasil-4™ in 2018 although the coverage is insignificant. Recently emerging reports are in favor of gender-neutral vaccination strategies with moderate coverage that was found superior and would rapidly eradicate high-risk HPVs than vaccinating only girls.

Conclusions

Cervical cancer continues to be a major public health problem affecting thousands of women in Ethiopia. As the disease is purely preventable, classic cervical cancer prevention strategies that include HPV vaccination using a broad genotype coverage, screening using a high precision test, and treating cervical precancerous lesions in the earliest possible time could prevent most cervical cancer cases in Ethiopia. The provision of a focused health education supported by educational materials would increase the knowledge of women about cervical cancer in general and the uptake of cervical cancer prevention and screening services in particular.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

Price excludes VAT (USA) Tax calculation will be finalised during checkout.

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Adopted from WHO ( Guidelines for screening and treatment of precancerous lesions for cervical cancer prevention, 2013) . Program managers and decision-makers can start at the top and answer the questions accordingly to determine which screen-and-treat option is best in the context where it will be implemented. It highlights choices related to resources, which can include costs, staff and training

Similar content being viewed by others

Human papillomavirus genotype distribution in Ethiopia: an updated systematic review

National genotype prevalence and age distribution of human papillomavirus from infection to cervical cancer in Japanese women: a systematic review and meta-analysis protocol

Factors Influencing the Cost-Effectiveness Outcomes of HPV Vaccination and Screening Interventions in Low-to-Middle-Income Countries (LMICs): A Systematic Review

Data availability.

All the generated data are included in the manuscript.

Abbreviations

Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia

Human papillomavirus

International agency for research on cancer

Sexually transmitted disease

Visual inspection of the cervix with acetic acid

World health organization

Hull R, Mbele M, Makhafola T, Hicks C, Wang S-M, Reis RM, Mehrotra R, Mkhize-Kwitshana Z, Kibiki G, Bates DO et al (2020) Cervical cancer in low and middle-income countries. Oncol Lett 20(3):2058–2074

Article CAS Google Scholar

World Health Organization (WHO). Cervical cancer. Available from ( http://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cervical-cancer) . Accessed on 17 Aug 2022

Cancer tomorrow: estimated number of cervical cancer incidence and mortality in Ethiopia ( https://gco.iarc.fr/tomorrow/en/dataviz/isotype?cancers=23&single_unit=500&populations=231&group_populations=1&multiple_populations=1&sexes=0&types=1&age_start=0 )

Integrated Africa cancer factsheet focusing on cervical cancer ( http://www.who.int/pmnch/media/events/2014/africa_cancer_factsheet.pdf )

Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A (2018) Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: A Cancer J Clin 68(6):394–424

Google Scholar

De Vuyst H, Alemany L, Lacey C, Chibwesha CJ, Sahasrabuddhe V, Banura C, Denny L, Parham GP (2013) The burden of human papillomavirus infections and related diseases in sub-saharan Africa. Vaccine 31(5):F32-46

Article Google Scholar

Cohen PA, Jhingran A, Oaknin A, Denny L (2019) Cervical cancer. Lancet 393(10167):169–182

Forman D, de Martel C, Lacey CJ, Soerjomataram I, Lortet-Tieulent J, Bruni L, Vignat J, Ferlay J, Bray F, Plummer M et al (2012) Global burden of human papillomavirus and related diseases. Vaccine 30(Suppl 5):F12-23

WHO: Guidelines for screening and treatment of precancerous lesions for cervical cancer prevention. In: World Health Organization, 20 Avenue Appia, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland 2013.

HPV detection and genotyping using the luminex xMAP technology ( http://www.irma-international.org/viewtitle/40440/ )

Maine D, Hurlburt S, Greeson D (2011) Cervical cancer prevention in the 21st century: cost is not the only issue. Am J Public Health 101(9):1549–1555

Santos-Lopez G, Marquez-Dominguez L, Reyes-Leyva J, Vallejo-Ruiz V (2015) General aspects of structure, classification and replication of human papillomavirus. Rev Med Inst Mex Seguro Soc 53(2):S166-171

Human papillomavirus (HPV) and cervical cancer ( http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs380/en/ )

ICO/IARC information centre on HPV and cancer (HPV information centre). Human papillomavirus and related diseases in the world. Summary report 2017. ( http://www.hpvcentre.net/statistics/reports/XWX.pdf )

Chow LT, Broker TR, Steinberg BM (2010) The natural history of human papillomavirus infections of the mucosal epithelia. APMIS 118(6–7):422–449

Doorbar J, Quint W, Banks L, Bravo IG, Stoler M, Broker TR, Stanley MA (2012) The biology and life-cycle of human papillomaviruses. Vaccine 20(30):083

Wallace NA, Galloway DA (2015) Novel functions of the human papillomavirus E6 oncoproteins. Annu Rev Virol 2(1):403–423

Human papillomavirus and related diseases report ( http://www.hpvcentre.net/statistics/reports/XWX.pdf )

Yugawa T, Kiyono T (2009) Molecular mechanisms of cervical carcinogenesis by high-risk human papillomaviruses: novel functions of E6 and E7 oncoproteins. Rev Med Virol 19(2):97–113

Yugawa T, Kiyono T (2008) Molecular basis of cervical carcinogenesis by high-risk human papillomaviruses. Uirusu 58(2):141–154

Arbyn M, Weiderpass E, Bruni L, de Sanjosé S, Saraiya M, Ferlay J, Bray F (2020) Estimates of incidence and mortality of cervical cancer in 2018: a worldwide analysis. Lancet Glob Health 8(2):e191–e203

Anorlu RI (2008) Cervical cancer: the sub-Saharan African perspective. Reprod Health Matters 16(32):41–49

Cervical Cancer ( https://www.afro.who.int/health-topics/cervical-cancer )

Jedy-Agba E, Joko WY, Liu B, Buziba NG, Borok M, Korir A, Masamba L, Manraj SS, Finesse A, Wabinga H et al (2020) Trends in cervical cancer incidence in sub-Saharan Africa. Br J Cancer 123(1):148–154

25ICO/IARCInformation Centre on HPV and Cancer (HPV Information Centre). Human papillomavirus and related diseases in Ethiopia. ( https://hpvcentre.net/statistics/reports/ETH.pdf )

Deksissa ZM, Tesfamichael FA, Ferede HA (2015) Prevalence and factors associated with VIA positive result among clients screened at family guidance association of Ethiopia, south west area office, Jimma model clinic, Jimma, Ethiopia 2013: a cross-sectional study. BMC Res Notes 8:618

Megbaru S (2015) Trends of cervical cancer in Ethiopia. Gynecol Obstet 5(103):1

Tsehay B, Afework M (2020) Precancerous lesions of the cervix and its determinants among Ethiopian women: systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 15(10):e0240353

Derbie A, Daniel M, Mezgebu Y, BIadgelgne F (2019) Magnitude of cervical lesions and its associated factors using visual inspection with acetic acid (VIA) at a referral hospital in Ethiopia. Ethiop Med J 57(2):1

Hailu A, Mariam DH (2013) Patient side cost and its predictors for cervical cancer in Ethiopia: a cross sectional hospital based study. BMC Cancer 13(1):69

Hailu A (2013) Patient cost of cervical cancer “immense” in Ethiopia. PharmacoEcon Outcomes News 674(1):7–7

Hagos A, Yitayal M, Kebede A, Debie A (2020) Economic burden and predictors of cost variability among adult cancer patients at comprehensive specialized hospitals in West Amhara, Northwest Ethiopia, 2019. Cancer Manag Res 12:11793–11802

Derbie A, Mekonnen D, Misgan E, Alemu YM, Woldeamanuel Y, Abebe T (2021) Low level of knowledge about cervical cancer among Ethiopian women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Infect Agent Cancer 16(1):11

Mesafint Z, Berhane Y, Desalegn D (2018) Health seeking behavior of patients diagnosed with cervical cancer in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Sci 28(2):111–116

Getahun F, Addissie A, Negash S, Gebremichael G (2019) Assessment of cervical cancer services and cervical cancer related knowledge of health service providers in public health facilities in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. BMC Res Notes 12(1):675

Begoihn M, Mathewos A, Aynalem A, Wondemagegnehu T, Moelle U, Gizaw M, Wienke A, Thomssen C, Worku D, Addissie A et al (2019) Cervical cancer in Ethiopia—predictors of advanced stage and prolonged time to diagnosis. Infect Agents Cancer 14(1):36

Kassie AM, Abate BB, Kassaw MW, Aragie TG, Geleta BA, Shiferaw WS (2020) Impact of knowledge and attitude on the utilization rate of cervical cancer screening tests among Ethiopian women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 15(12):e0239927

Molecular epidemiology of human papillomavirus in north and central part of Ethiopia ( http://etd.aau.edu.et/handle/123456789/14079 )

Abu SH, Woldehanna BT, Nida ET, Tilahun AW, Gebremariam MY, Sisay MM (2020) The role of health education on cervical cancer screening uptake at selected health centers in Addis Ababa. PLoS ONE 15(10):e0239580

Agide FD, Garmaroudi G, Sadeghi R, Shakibazadeh E, Yaseri M, Koricha ZB, Tigabu BM (2018) A systematic review of the effectiveness of health education interventions to increase cervical cancer screening uptake. Eur J Pub Health 28(6):1156–1162

Dias TC, Longatto-Filho A, Campanella NC (2020) Human papillomavirus genotyping as a tool for cervical cancer prevention: from commercially available human papillomavirus DNA test to next-generation sequencing. Future Sci OA 6(9):603

Münger K, Baldwin A, Edwards KM, Hayakawa H, Nguyen CL, Owens M, Grace M, Huh K (2004) Mechanisms of human papillomavirus-induced oncogenesis. J Virol 78(21):11451–11460

Williams VM, Filippova M, Soto U, Duerksen-Hughes PJ (2011) HPV-DNA integration and carcinogenesis: putative roles for inflammation and oxidative stress. Futur Virol 6(1):45–57

Kajitani N, Satsuka A, Kawate A, Sakai H (2012) Productive lifecycle of human papillomaviruses that depends upon squamous epithelial differentiation. Front Microbiol 3:152

Narisawa-Saito M, Kiyono T (2007) Basic mechanisms of high-risk human papillomavirus-induced carcinogenesis: roles of E6 and E7 proteins. Cancer Sci 98(10):1505–1511

Harald zur Hausen’s experiments on human papillomavirus causing cervical cancer (1976–1987): embryo project encyclopedia (2017-03-09) ( https://embryo.asu.edu/pages/harald-zur-hausens-experiments-human-papillomavirus-causing-cervical-cancer-1976-1987 )

Bouvard V, Baan R, Straif K, Grosse Y, Secretan B, El Ghissassi F, Benbrahim-Tallaa L, Guha N, Freeman C, Galichet L et al (2009) A review of human carcinogens—Part B biological agents. Lancet Oncol 10(4):321–322

Zhai L, Tumban E (2016) Gardasil-9: a global survey of projected efficacy. Antivir Res 130:101–109

Derbie A, Mekonnen D, Nibret E, Maier M, Woldeamanuel Y, Abebe T (2022) Human papillomavirus genetype distribution in Ethiopia: an updated systematic review. Virol J 19:3

Teka B, Gizaw M, Ruddies F, Addissie A, Chanyalew Z, Skof AS, Thies S, Mihret A, Kantelhardt EJ, Kaufmann AM et al (2021) Population-based human papillomavirus infection and genotype distribution among women in rural areas of South Central Ethiopia. Int J Cancer 148(3):723–730

Bruni L, Diaz M, Castellsagué X, Ferrer E, Bosch F, de Sanjosé S (2010) Cervical human papillomavirus prevalence in 5 continents: meta-analysis of 1 million women with normal cytological findings. J Infect Dis 202:1789–1799. https://doi.org/10.1086/657321

Pimenoff N, Tous S, Benavente Y, Alemany L, Quint W, Bosch F, Bravo G, Sanjosé S (2019) Distinct geographic clustering of oncogenic human papillomaviruses multiple infections in cervical cancers: results from a worldwide cross-sectional study. Int J Cancer 144:2478–2488. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.31964

Sanjose S, Quint G, Alemany L, Geraets T, Klaustermeier E, Lloveras B et al (2010) Human papillomavirus genotype attribution in invasive cervical cancer: a retrospective cross-sectional worldwide study. Lancet Oncol 11:1048–1056. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70230-8

Leto M, Santos Junior GF, Porro AM, Tomimori J (2011) Human papillomavirus infection: etiopathogenesis, molecular biology and clinical manifestations. An Bras Dermatol 86(2):306–317

García DA, Cid-Arregui A, Schmitt M, Castillo M, Briceño I, Aristizábal FA (2011) Highly sensitive detection and genotyping of hpv by pcr multiplex and luminex technology in a cohort of colombian women with abnormal cytology. Open Virol J 5:70–79

Pimple S, Mishra G, Shastri S (2016) Global strategies for cervical cancer prevention. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 28(1):4–10

Sahasrabuddhe VV, Luhn P, Wentzensen N (2011) Human papillomavirus and cervical cancer: biomarkers for improved prevention efforts. Future Microbiol 6(9):1083–1098

Tian Q, Li Y, Wang F, Xu J, Shen Y, Ye F, Wang X, Cheng X, Chen Y, Wan X et al (2014) MicroRNA Detection in Cervical Exfoliated Cells as a Triage for Human Papillomavirus-Positive Women. J Natl Cancer Inst. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/dju241

Wang HY, Lee D, Park S, Kim G, Kim S, Han L, Yubo R, Li Y, Park KH, Lee H (2015) Diagnostic performance of HPV E6/E7 mRNA and HPV DNA assays for the detection and screening of oncogenic human papillomavirus infection among woman with cervical lesions in China. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 16(17):7633–7640

Cuschieri K, Wentzensen N (2008) Human papillomavirus mRNA and p16 detection as biomarkers for the improved diagnosis of cervical neoplasia. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev 17(10):2536–2545

WHO (2015) ICO centre on HPV and cancer (HPV information centre). human papillomavirus and related diseases report

Sankaranarayanan R, Anorlu R, Sangwa-Lugoma G, Denny LA (2013) Infrastructure requirements for human papillomavirus vaccination and cervical cancer screening in sub-Saharan Africa. Vaccine 29(31):066

Tadesse SK (2015) Preventive mechanisms and treatment of cervical cancer in Ethiopia. Gynecol Obstet. https://doi.org/10.4172/2161-0932.S3:101

Louie KS, de Sanjose S, Mayaud P (2009) Epidemiology and prevention of human papillomavirus and cervical cancer in sub-Saharan Africa: a comprehensive review. Trop Med Int Health 14(10):1287–1302

WHO guidelines for screening and treatment of precancerous lesions for cervical cancer prevention. ( https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/94830/9789241548694_eng.pdf )

Eshete M, Abdulwuhab Atta M, Yeshita HY (2020) Cervical cancer screening acceptance among women in Dabat District, Northwest Ethiopia, 2017: an institution-based cross-sectional study. Obstet Gynecol Int 2020:2805936

Ruddies F, Gizaw M, Teka B, Thies S, Wienke A, Kaufmann AM, Abebe T, Addissie A, Kantelhardt EJ (2020) Cervical cancer screening in rural Ethiopia: a cross-sectional knowledge, attitude and practice study. BMC Cancer 20(1):563

Getachew S, Getachew E, Gizaw M, Ayele W, Addissie A, Kantelhardt EJ (2019) Cervical cancer screening knowledge and barriers among women in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. PLoS ONE 14(5):e0216522

Bayu H, Berhe Y, Mulat A, Alemu A (2016) Cervical cancer screening service uptake and associated factors among age eligible women in mekelle zone, Northern Ethiopia, 2015: a community based study using health belief model. PLoS ONE 11(3):e0149908

Nigussie T, Admassu B, Nigussie A (2019) Cervical cancer screening service utilization and associated factors among age-eligible women in Jimma town using health belief model, South West Ethiopia. BMC Womens Health 19(1):127

Assefa AA, Astawesegn FH, Eshetu B (2019) Cervical cancer screening service utilization and associated factors among HIV positive women attending adult ART clinic in public health facilities, Hawassa town, Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv Res 19(1):847

Dessalegn Mekonnen B (2020) Cervical cancer screening uptake and associated factors among HIV-positive women in ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Adv Prev Med 2020:7071925

Ayenew AA, Zewdu BF, Nigussie AA (2020) Uptake of cervical cancer screening service and associated factors among age-eligible women in Ethiopia: systematic review and meta-analysis. Infect Agent Cancer 15(1):67

Wondimu YT (2015) cervical cancer: assessment of diagnosis and treatment facilities in public health institutions in addis ababa, ethiopia. Ethiop Med J 53(2):65–74

Vänskä S, Luostarinen T, Baussano I, Apter D, Eriksson T, Natunen K et al (2020) Vaccination with moderate coverage eradicates oncogenic human papillomaviruses if a gender-neutral strategy is applied. J Infect Dis. https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jiaa099

Lehtinen M, Luostarinen T, Vänskä S, Söderlund-Strand A, Eriksson T, Natunen K et al (2018) Gender-neutral vaccination provides improved control of human papillomavirus types 18/31/33/35 through herd immunity: results of a community randomized trial (III). Int J Cancer 142(5):949–958. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.31119

Download references

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Bahir Dar and Addis Ababa Universities and CDT-Africa for the provided opportunity to undertake this review.

We received no funds for this particular review.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Medical Microbiology, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Bahir Dar University, Bahir Dar, Ethiopia

Awoke Derbie & Daniel Mekonnen

Centre for Innovative Drug Development and Therapeutic Trials for Africa (CDT-Africa), Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

Awoke Derbie & Yimtubezinash Woldeamanuel

Department of Health Biotechnology, Biotechnology Research Institute, Bahir Dar University, Bahir Dar, Ethiopia

Department of Medical Microbiology, Immunology and Parasitology, College of Health Sciences, Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

Awoke Derbie, Yimtubezinash Woldeamanuel & Tamrat Abebe

Department of Biology, College of Science, Bahir Dar University, Bahir Dar, Ethiopia

Endalkachew Nibret

Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Bahir Dar University, Bahir Dar, Ethiopia

Eyaya Misgan

Department of Diagnostics, Institute of Virology, Leipzig University Hospital, Leipzig, Germany

Melanie Maier

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

AD and TA conceived the review topic and objectives. AD, DM and EM participated in the study selection and write-up. EN, MM, YW and TA reviewed the manuscript critically for its scientific content. All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Awoke Derbie .

Ethics declarations

Competing interest.

Authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Ethical approval

Not applicable in this section.

Consent to participate

Consent for publication, additional information, publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Derbie, A., Mekonnen, D., Nibret, E. et al. Cervical cancer in Ethiopia: a review of the literature. Cancer Causes Control 34 , 1–11 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-022-01638-y

Download citation

Received : 04 January 2022

Accepted : 26 September 2022

Published : 15 October 2022

Issue Date : January 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-022-01638-y

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Cervical cancer

- Human papillomavirus (HPV)

- Vaccination

- Cervical screening

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Knowledge and awareness of cervical cancer in Southwestern Ethiopia is lacking: A descriptive analysis

Atif saleem, alemayehu bekele, megan b fitzpatrick, eiman a mahmoud, athena w lin, h eduardo velasco, mona m rashed.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

* E-mail: [email protected]

Contributed equally.

Received 2019 Mar 26; Accepted 2019 Oct 23; Collection date 2019.

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Cervical cancer remains the second most common cancer and cancer-related death among women in Ethiopia. This is the first study, to our knowledge, describing the demographic, and clinicopathologic characteristics of cervical cancer cases in a mainly rural, Southwestern Ethiopian population with a low literacy rate to provide data on the cervical cancer burden and help guide future prevention and intervention efforts.

A descriptive analysis of 154 cervical cancer cases at the Jimma University Teaching Hospital in Southwestern Ethiopia from January 2008 –December 2010 was performed. Demographic and clinical characteristics were obtained from patient questionnaires and cervical punch biopsies were histologically examined.

Of the 154 participants with a histopathologic diagnosis of cervical cancer, 95.36% had not heard of cervical cancer and 89.6% were locally advanced at the time of diagnosis. Moreover, 86.4% of participants were illiterate, and 62% lived in a rural area.

A majority of the 154 women with cervical cancer studied at the Jimma University Teaching Hospital in Southwestern Ethiopia were illiterate, had not heard of cervical cancer and had advanced disease at the time of diagnosis. Given the low rates of literacy and knowledge regarding cervical cancer in this population which has been shown to correlate with a decreased odds of undergoing screening, future interventions to address the cervical cancer burden here must include an effective educational component.

Introduction

Cervical cancer pathology and demographic data is lacking from Southwestern Ethiopia. The Jimma University Teaching Hospital (JUTH) is located in the city of Jimma which is 352 km southwest of Ethiopia’s capital city Addis Ababa and is unique in that it acts as the only teaching and referral hospital in the region, serving a population of 15 million people [ 1 ]. Moreover, Jimma is part of the Oromia state which has one of the highest poverty rates (74.9% of the population) and lowest literacy rates in the country (36% of all residents, with 17% of the female residents living in rural settings) [ 2 – 3 ]. Contributory data from this hospital is vital since every year, an estimated 7,095 women are diagnosed with cervical cancer and 4,732 deaths are due to the disease in Ethiopia—it is currently the second most common cause of female cancer deaths in Ethiopia, after breast cancer.

Infection with high-risk human papillomavirus (HPV) is the necessary cause of >99% of cervical cancer [ 4 ]. Other contributing factors include smoking, total fertility rate, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection [ 5 ]. The knowledge about cervical cancer in Ethiopia has been reported to range from 21.2% to 53.7%, with screening rates that ranged from 9.9% to 23.5%. Three of these four studies, however, took place in Northern Ethiopia [ 6 – 9 ]. Though there is not yet an organized cervical cancer education or screening program in Ethiopia, the ongoing dilemma remains how much the absence of such programs compared to a general lack of education or negative attitude towards cervical cancer contribute to the disease burden. Aweke et al. described that 34.8% of 583 survey respondents in Southern Ethiopia had a negative attitude pertaining to cervical cancer [ 7 ].

Materials and methods

Place of study.

The study took place at the Jimma University Teaching Hospital Departments of Obstetrics and Gynecology and Medical Laboratory Sciences and Pathology in Southwestern Ethiopia. This study, including the verbal/oral consent procedure, was approved by the Touro University California Institutional Review Board in the United States of America, by the Research and Publication Committee of the Faculty of Medical Sciences at Jimma University, by the Jimma University Ethics Review Committee and by the Jimma University Teaching Hospital Departments of Obstetrics and Gynecology and Medical Laboratory Sciences and Pathology in Ethiopia. Verbal/oral consent was only able to be obtained as opposed to written consent given that a significant proportion of the study population was not literate. The verbal/oral consent was recorded by the residents who were interviewing the subjects/performing the procedure onto individual survey sheets, which were then transcribed into a central document.

Study population

The study population included non-pregnant women voluntarily attending the Jimma University Teaching Hospital Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology outpatient clinic from January 2008 –December 2010 who had evidence of cervical lesions on initial pelvic examination. All of the participants voluntarily presented to the clinic and were willing to be screened; data was collected only after full informed oral consent for participating in the study was obtained.

Screening procedure

Data was collected by residents in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology who were informed regarding the study parameters and were in charge of the outpatient service on a rotation basis. All non-pregnant women with cervical lesions were invited to participate during the study time period. The patients were informed about the indications, contraindications, and alternative options of undergoing a cervical punch biopsy to recognize any cervical pathology. Oral consent was obtained from each case before the interview, punch biopsy procedure and data collection for participation in the study. Then each patient was interviewed using a standardized questionnaire ( S1 File ) to extract information regarding additional clinical features, sociodemographic characteristics, maternity history, and knowledge about cervical carcinoma, amongst others. Questionnaires were collected weekly and checked for adequacy—those with inadequate data (missing data or unrecognizable responses) were excluded. Pelvic examination was conducted to characterize the cervical lesion(s) and determine the clinical stage. Thorough speculum examination of the cervix was performed to describe any lesion(s) and subsequently a four quadrant punch biopsy of the cervix was taken. The biopsy material was preserved in 10% formaldehyde and submitted to the Department of Medical Laboratory Sciences and Pathology.

In the Department of Pathology the formalin fixed tissue was embedded in paraffin, sections were cut and subsequently stained as described. From each case, four microscopic slides were prepared–one remained in the Department of Pathology for clinical management and three were used for the current study. The slide used for clinical management was stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and diagnosed by a pathologist in the Department of Pathology according to the World Health Organization histological classification of tumors of the uterine cervix and this pathologic report was recorded and relayed to the physician specific to the case for clinical care. The H&E study slides were identified by the biopsy and code number assigned by the initial physician on the biopsy request sheet and questionnaire and were submitted for diagnosis to a pathologist from Touro University California who was blinded regarding the case for quality control. If there was disagreement in the reports between the slide used for clinical management and the second observer report, the slide was given to a third pathologist and the agreement of the two pathologists was taken as the gold standard report to be recorded.

Data analysis

Data was initially entered into Microsoft Excel after which it was coded and analyzed using STATA 15.0 software. Data cleaning was performed only in the form of eliminating missing data so as to improve accuracy, and descriptive statistics were subsequently used to summarize all variables.

A total of 240 women presented with various gynecological complaints to the outpatient clinic from January 2008 –December 2010. Eighty six women were excluded: 30 of these women had a diagnosis other than cervical cancer such as cervicitis or a cervical polyp but their remaining data was insufficient to analyze; the remaining 56 women were excluded due to an uninterpretable or equivocal biopsy. This left 154 cases to be analyzed and their subjective and objective clinical data is summarized in Tables 1 – 3 .

Table 1. Selected demographic and clinical features of 154 cervical cancer cases at the Jimma University Teaching Hospital, Ethiopia from January 2008—December 2010.

IQR: Interquartile range

Table 3. Selected objective clinical features of 154 cervical cancer cases at the Jimma University Teaching Hospital, Ethiopia from January 2008—December 2010.

Table 2. selected non-quantifiable demographic and clinical features of 154 cervical cancer cases at the jimma university teaching hospital, ethiopia from january 2008—december 2010..

a Other ethnicities included Shekicho, Gurage, Kulo, Yem, Kefa, Dawro, and Bench.

b Amongst those that admitted to using contraception, none practiced barrier contraception- only oral contraceptive pills or injectable contraceptives were used.

c Out of those that have heard of cervical cancer, all denied knowing the cause of it.

Demographic and clinical features

Cervical cancer is a unique cancer in that effective screening methods are known to prevent disease and associated mortality. Knowledge about the disease and preventive options are vital to effectively control the disease; however, we highlight in the current study that there is a considerable lack of knowledge and awareness regarding cervical cancer which is the second most common cause of cancer deaths in Ethiopia.

Knowledge about cervical cancer in Ethiopia has been reported to range from 21.2% to 53.7% [ 6 – 9 ], and Aweke et. Al described that 34.8% (n = 583) of survey respondents in Southern Ethiopia had a negative attitude pertaining to cervical cancer [ 7 ]. In our study a majority 144 women (95.36%) had not heard of cervical cancer compared to 138 out of 633 women (21.8%) who had not heard of it in a study done in Gondar town, northwest Ethiopia in 2010 [ 6 ]. In that cross-sectional survey, the literacy rate was 18.8%, whereas the rate was 86.4% in our current study. Moreover, a majority of our study participants lived in rural areas (62%) where access to television/radio and health professionals is limited- these were noted as the two most common sources for hearing about cervical cancer in the aforementioned study. The lack of knowledge regarding cervical cancer is of note since preventative efforts such as screening have been shown to reduce the risk of cervical cancer compared to no screening [ 10 ]; furthermore, a single-visit approach for cervical cancer screening in Ethiopia was described by Addis Tesfa in 2010 where visual inspection of the cervix with acetic acid wash (VIA) with subsequent cryotherapy of premalignant lesions was performed. One VIA at age 35 can reduce a woman’s lifetime risk of cervical cancer by 25% and if screened again at age 40 by 65% [ 11 ].

Cervical cancer educational strategies have been shown to improve screening in studies which targeted rural populations of sub-Saharan Africa [ 12 – 14 ]. Erku et al. describe that the odds of undergoing cervical cancer screening among women who had a comprehensive knowledge on cervical cancer and screening were 2.02 times higher than those who did not in a northwest Ethiopian population. In this study, a majority (87.7%) of the respondents had heard of cervical cancer. This is likely an overestimate since this study included a population of women living with HIV/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) which may have an increased level of awareness with more frequent healthcare visits [ 8 ].

In Ethiopia, currently there are approximately 25 cervical cancer screening centers that are providing visual inspection with acetic acid (VIA), however there is low participation in the community which is partly attributed to the lack of awareness regarding this disease [ 15 ]. Geremew et al describe that college and above educational status, knowing someone with cervical cancer, and having knowledge of cervical cancer were positively associated with favorable attitudes towards cervical cancer screening [ 16 ]; in the current study, a majority of the patients were illiterate and had decreased knowledge regarding cervical cancer which may explain the lack of screening in our specific population. The National Cancer Control Plan of Ethiopia headed by the Federal Ministry of Health Ethiopia plans a nation-wide scale up of the screening and treatment of cervical pre-cancerous lesions into over 800 health facilities [ 17 ]. The mean age at diagnosis of cervical cancer in the United States has been shown to be 48 years and in our study from Ethiopia it was 45 years [ 18 ]. Our study differs in that there is no data on prior screening which may have decreased the age at diagnosis and if so, could be attributed to a possible faster progression from HPV to cervical cancer secondary to HIV co-infection or other synergistic risk factors, particularly in the absence of a cervical cancer screening program. Established risk factors for most cervical cancer include: early onset of sexual activity, multiple sexual partners, immunosuppression, increasing parity, low socioeconomic status and oral contraceptive use [ 5 ].

A qualitative study of 198 patients with cervical cancer from Tikur Anbessa Hospital in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia in 2013 [ 19 ] is compared to our study at JUTH in Table 4 . The mean age at first sexual intercourse in southwestern Ethiopia has previously been shown to be 17.07 years (+/- 2.12) in a group of 405 young women where cervical lesions were not studied [ 20 ]. Our data of cervical cancer cases shows the mean age at first sexual intercourse to be 15.83 years (+/- 2.08) and the mean age from the Tikbur Anbessa study is 16.5 years which may be explained by the cultural practice of marriage at a younger age in these selected populations.

Table 4. Comparison of data pertinent to selected risk factors for cervical cancer from Jimma University Teaching Hospital in southwestern Ethiopia (January 2008—December 2010) and Tikbur Anbessa Hospital in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia (April 2013) [ 19 ] from women with a diagnosis of cervical cancer to that of representative women in Ethiopia (where cervical lesions were not necessarily studied).

a (Out of 198 respondents, 52.3% responded 1, 33% responded 2 and 29% responded 3 or more).

Prior studies found that the mean number of sexual partners in Ethiopia for women is approximately 1.5 (cervical lesions not specified) compared to our study which is 2.9 [ 21 – 22 ] and an increased number of sexual partners raises the probability of becoming infected with HPV. The total fertility rate is estimated to be 4.8 children per woman in Ethiopia (cervical lesions not specified) compared to our study which is 6.27 per woman. The proposed mechanism for higher parity as a risk factor for cervical cancer include increased estrogen exposure during pregnancy, persistence of the transformation zone on the ectocervix in multiparous women, and cervical tissue damage during vaginal deliveries [ 22 ].

Hormonal steroids (such as those in oral contraceptive pills) have been shown to activate enhancer elements in the upstream regulatory region of the HPV type 16 viral genome which is one proposed mechanism for the increased risk of cervical cancer [ 23 ]. Out of the 35 women (23.33%) in our study used contraception, none practiced barrier contraception. The majority of these 35 women (80%) used oral contraceptive pills which have been shown to increase the cumulative incidence of invasive cervical cancer by age 50 from 7.3 to 8.3 per 1000 in developing countries [ 24 ].

This study took place during the rapid expansion phase of HIV/AIDS services in Ethiopia where the number of patients on antiretroviral therapy (ART) increased from 900 at the beginning of 2005 to over 150,000 by June 2008 [ 25 ]. Despite this increase in ART use, the frequency of cervical cancer cases in Ethiopia has increased from 2005 until present, with a yearly increment from 1997–2012 except in 1999 and 2009 [ 26 ]. This increase may, however, be attributed to increased awareness, screening and subsequent diagnosis. In our study, a majority of women presented at stage IIB followed by stage IIIA at the time of diagnosis and the general trends in Ethiopia at that time remained at presenting at stage IIIB being the most frequent, and secondly stage IIB ( Table 5 ).

Table 5. Clinical stages of cervical carcinoma cases at presentation.

Histopathologic classification.

The majority of cervical cancers in the United States are squamous cell carcinoma (69%) followed by adenocarcinoma (25%) [ 27 ]. Histopathologic subtype classification in a study of 598 cervical cancer cases in Nigeria and 2,930 cervical cancer cases in South Africa demonstrated squamous cell carcinoma as the most common type as was shown in 92.3% and greater than 80% of cases, respectively [ 28 – 29 ]. In the United States, other non-squamous cervical cancers have been observed in the following frequencies: adenosquamous carcinomas represent 20%-30% of all adenocarcinomas of the cervix and small cell carcinomas represent 0.5%-5% of all invasive cervical cancers. In our study, approximately 91% of the cervical cancer cases were squamous cell carcinomas (including keratinizing, non-keratinizing and basaloid subtypes), 5.84% were small cell carcinomas, 2.59% were adenocarcinomas, and 0.64% were adenosquamous carcinomas. The squamous cell carcinoma frequency was similar to that observed in prior studies; however, an increased frequency of small cell carcinomas over adenocarcinomas was also noted in our study. It has been shown that the keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma subtype is associated with a higher likelihood of advanced stage disease and a lower overall 5-year survival [ 30 ] and in our study we observed a 51.29% frequency of this subtype.

The HPV-18 genotype is more commonly associated with adenocarcinomas and small cell carcinomas of the cervix; however, the cases in this study were not subtyped. Few studies describing the high-risk HPV genotypes have been performed in Ethiopia out of which one study of 98 women with cervical dysplasia in Jimma showed that HPV-18 was detected in 8.2% of the 67.1% of HPV DNA positive samples [ 31 ]. Based on other studies, HPV type 18 is detected in 18.2% of cervical cancer cases in Ethiopia [ 32 ].

A population based study from 1988–2004 of 6,853 women with squamous cell carcinoma found that keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix may be less radiosensitive and associated with shorter overall survival than non-keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma [ 30 ]. In our study, a majority of women presented with locally advanced cervical cancer (89.6%, Table 5 ), whereas approximately 54.9–58.8% of patients were diagnosed at a late stage in a California database from the United States [ 33 ], as a means of comparison to a high-income country with an established screening program in place. We believe the majority of women in our study presented with locally advanced lesions not entirely due to an intrinsic pathogenetic difference, but because of lack of a cervical screening program in Ethiopia, decreased knowledge about cervical cancer, inability to attend health clinics due to cost and travel expenditure, and increased exposure to risk factors.

Limitations, future directions and recommendations

Our study did not perform laboratory confirmation of HPV or HIV infection, or test for co-infections with other sexually transmitted infections. Recall bias may have affected the demographic data since it was procured by a survey. Future directions include measuring survival outcomes after intervention for cervical cancer and studying the effectiveness of cervical cancer screening after education. Based on our data, in this specific population of Ethiopian women we recommend promoting an educational initiative about cervical cancer among Ethiopian women given that improved knowledge regarding the disease has been shown to increase screening and decrease cervical cancer rates.

Conclusions

Most of the 154 women with cervical cancer studied at the JUTH in southwestern Ethiopia were illiterate, had not heard of cervical cancer, had advanced disease at the time of diagnosis and had microscopically confirmed squamous cell carcinomas. The low rates of literacy and knowledge regarding cervical cancer in this population were also associated with lower screening rates. Future interventions to address the cervical cancer burden in Ethiopia should include an effective educational component which has been shown to increase screening rates and ultimately decrease the cervical cancer incidence.

Supporting information

Each patient was orally interviewed by residents using this standardized questionnaire who then input the information accordingly. The histopathology data (Section IV) was completed by a pathologist.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the Jimma University Teaching Hospital and the Global Physicians Corps for their technical support in this study, and to the Touro University California Institutional Review Board in the United States of America, the Research and Publication Committee of the Faculty of Medical Sciences at Jimma University, the Jimma University Ethics Review Committee and the Jimma University Teaching Hospital Departments of Obstetrics and Gynecology and Medical Laboratory Sciences and Pathology in Ethiopia for their approval and permission to perform this study. We would also like to acknowledge all of the physicians/trainees/staff who assisted in data collection and to all of the study participants who provided this vital data in an overall effort to study and reduce the morbidity/mortality attributed to cervical cancer.

Data Availability

The data underlying the results presented in the study has been de-identified and is available from: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor], 2019-10-04. https://doi.org/10.3886/E112185V1 .

Funding Statement

This study was funded in terms of the materials (questionnaires, histopathological materials including microscopic slides/staining materials) by the Jimma University Teaching Hospital and by the Global Physicians Corps ( http://globalphysicians.org/ ).

- 1. Jimma University Specialized Hospital: Historical Background: https://www.ju.edu.et/jimma-university-specialized-hospital-jush . Cited 20 March 2019.

- 2. Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative (OPHI) www.ophi.org.uk . Oxford Department of International Development. Queen Elizabeth House, University of Oxford. OPHI Country Briefing 2017: Ethiopia. Global Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI).

- 3. Adugna A. Oromiya: Demography and Health; 2017 [cited 2019 March 5]. http://www.ethiodemographyandhealth.org/Oromia.html .

- 4. Walboomers JM, Jacobs MV, Manos MM, Bosch FX, Kummer JA, Shah KV, et al. Human papillomavirus is a necessary cause of invasive cervical cancer worldwide. J Pathol. 1999;189(1):12–9. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 5. International Collaboration of Epidemiological Studies of Cervical Cancer. Comparison of risk factors for invasive squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma of the cervix: collaborative reanalysis of individual data on 8,097 women with squamous cell carcinoma and 1,374 women with adenocarcinoma from 12 epidemiological studies. Int J Cancer. 2007;120(4):885–91. 10.1002/ijc.22357 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 6. Getahun F, Mazengia F, Abuhay M, Birhanu Z. Comprehensive knowledge about cervical cancer is low among women in Northwest Ethiopia. BMC cancer. 2013. December;13(1):2. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 7. Aweke YH, Ayanto SY, Ersado TL. Knowledge, attitude and practice for cervical cancer prevention and control among women of childbearing age in Hossana Town Hadiya zone, Southern Ethiopia: Community-based cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2017. July 25;12(7):e0181415 10.1371/journal.pone.0181415 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 8. Erku DA, Netere AK, Mersha AG, Abebe SA, Mekuria AB, Belachew SA. Comprehensive knowledge and uptake of cervical cancer screening is low among women living with HIV/AIDS in Northwest Ethiopia. Gynecol Oncol Res Pract. 2017. December 19;4:20 10.1186/s40661-017-0057-6 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 9. Mitiku I, Tefera F. Knowledge about cervical cancer and associated factors among 15–49 year old women in Dessie Town, Northeast Ethiopia. PLoS One. 2016. September 30;11(9):e0163136 10.1371/journal.pone.0163136 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 10. Peirson L, Fitzpatrick-Lewis D, Ciliska D, Warren R. Screening for cervical cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Systematic reviews. 2013. December;2(1):35. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 11. Shiferaw N, Salvador-Davila G, Kassahun K, Brooks MI, Weldegebreal T, Tilahun Y, et al. The single-visit approach as a cervical cancer prevention strategy among women with HIV in Ethiopia: successes and lessons learned. Global Health: Science and Practice. 2016. March 21;4(1):87–98. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 12. Abiodun OA, Olu-Abiodun OO, Sotunsa JO, Oluwole FA. Impact of health education intervention on knowledge and perception of cervical cancer and cervical screening uptake among adult women in rural communities in Nigeria. BMC public health. 2014. December;14(1):814. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 13. Chigbu CO, Onyebuchi AK, Onyeka TC, Odugu BU, Dim CC. The impact of community health educators on uptake of cervical and breast cancer prevention services in Nigeria. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. 2017. June 1;137(3):319–24. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 14. Johnson LG, Armstrong A, Joyce CM, Teitelman AM, Buttenheim AM. Implementation strategies to improve cervical cancer prevention in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. Implementation Science. 2018. December;13(1):28 10.1186/s13012-018-0718-9 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 15. Teame H, Addissie A, Ayele W, Hirpa S, Gebremariam A, Gebreheat G, et al. Factors associated with cervical precancerous lesions among women screened for cervical cancer in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: A case control study. PloS one. 2018. January 19;13(1):e0191506 10.1371/journal.pone.0191506 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 16. Geremew AB, Gelagay AA, Azale T. Comprehensive knowledge on cervical cancer, attitude towards its screening and associated factors among women aged 30–49 years in Finote Selam town, northwest Ethiopia. Reproductive health. 2018. December;15(1):29 10.1186/s12978-018-0471-1 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 17. Federal Ministry of Health Ethiopia. National Cancer Control Plan 2015/2016-2019/2020. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: Federal Ministry of Health; 2015. [ Google Scholar ]

- 18. Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet‐Tieulent J, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2015. March;65(2):87–108. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 19. Tadesse SK. Socio-economic and cultural vulnerabilities to cervical cancer and challenges faced by patients attending care at Tikur Anbessa Hospital: a cross sectional and qualitative study. BMC women’s health. 2015. December;15(1):75. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 20. Tilahun M, Ayele G. Factors associated with age at first sexual initiation among youths in Gamo Gofa, south west Ethiopia: a cross sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2013. December;13(1):622. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 21. CSA-Ethiopia IC. International: Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2011. 2012. Maryland, USA: Central Statistical Agency of Ethiopia and ICF International Addis Ababa, Ethiopia and Calverton; 2011. [ Google Scholar ]

- 22. Jensen KE, Schmiedel S, Norrild B, Frederiksen K, Iftner T, Kjaer SK. Parity as a cofactor for high-grade cervical disease among women with persistent human papillomavirus infection: a 13-year follow-up. British journal of cancer. 2013. January;108(1):234 10.1038/bjc.2012.513 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 23. Moodley M, Moodley J, Chetty R, Herrington CS. The role of steroid contraceptive hormones in the pathogenesis of invasive cervical cancer: a review. International Journal of Gynecological Cancer. 2003. March;13(2):103–10. 10.1046/j.1525-1438.2003.13030.x [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 24. International Collaboration of Epidemiological Studies of Cervical Cancer. Cervical cancer and hormonal contraceptives: collaborative reanalysis of individual data for 16 573 women with cervical cancer and 35 509 women without cervical cancer from 24 epidemiological studies. The Lancet. 2007. November 10;370(9599):1609–21. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 25. Assefa Y, Jerene D, Lulseged S, Ooms G, Van Damme W. Rapid scale-up of antiretroviral treatment in Ethiopia: successes and system-wide effects. PLoS medicine. 2009. April 28;6(4):e1000056 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000056 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 26. Abate SM. Trends of cervical cancer in Ethiopia. Gynecol Obstet (Sunnyvale). 2015;5(103):2161–0932. [ Google Scholar ]

- 27. Rates RS. SEER cancer statistics review 1975–2004.

- 28. Olu-Eddo AN, Ekanem VJ, Umannah I, Onakevhor J. A 20 year histopathological study of cancer of the cervix in Nigerians. Nigerian quarterly journal of hospital medicine. 2011;21(2):149–53. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 29. Moodley M, Moodley K. Trends of histopathology of cervical cancer among women in Durban, South Africa. European journal of gynaecological oncology. 2009;30(2):145–50. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 30. Kumar S, Shah JP, Bryant CS, Imudia AN, Ali-Fehmi R, Malone JM Jr, et al. Prognostic significance of keratinization in squamous cell cancer of uterine cervix: a population based study. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2009. July;280(1):25–32. 10.1007/s00404-008-0851-9 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 31. Bekele A, Baay M, Mekonnen Z, Suleman S, Chatterjee S. Human papillomavirus type distribution among women with cervical pathology–a study over 4 years at Jimma Hospital, southwest Ethiopia. Tropical Medicine & International Health. 2010. August;15(8):890–3. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 32. Bruni L, Barrionuevo-Rosas L, Albero G, Serrano B, Mena M, Gómez D, et al. ICO Information Centre on HPV and Cancer (HPV Information Centre). Human Papillomavirus and Related Diseases in the World. Summary Report 7 October 2016.

- 33. Maguire FB, Chen Y, Morris CR, Parikh-Patel A, Kizer KW. Heat Maps: Trends in Late Stage Diagnoses of Screenable Cancers in California Counties, 1988–2013. Sacramento, CA: California Cancer Reporting and Epidemiologic Surveillance Program, Institute for Population Health Improvement, University of California Davis, June 2016. [ Google Scholar ]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data availability statement.

- View on publisher site

- PDF (394.4 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Cervical cancer screening utilization and predictors among eligible women in Ethiopia: A systematic review and meta-analysis

Melaku desta, temesgen getaneh, bewuket yeserah, yichalem worku, tewodros eshete, molla yigzaw birhanu, getachew mullu kassa, fentahun adane, yordanos gizachew yeshitila.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

* E-mail: [email protected]

Received 2020 Jul 23; Accepted 2021 Oct 18; Collection date 2021.

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Despite a remarkable progress in the reduction of global rate of maternal mortality, cervical cancer has been identified as the leading cause of maternal morbidity and mortality, particularly in sub-Saharan African countries. The uptake of cervical cancer screening service has been consistently shown to be effective in reducing the incidence rate and mortality from cervical cancer. Despite this, there are limited studies in Ethiopia that were conducted to assess the uptake of cervical cancer screening and its predictors, and these studies showed inconsistent and inconclusive findings. Therefore, this systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted to estimate the pooled cervical cancer screening utilization and its predictors among eligible women in Ethiopia.

Methods and findings

Databases like PubMed, Web of Science, SCOPUS, CINAHL, Psychinfo, Google Scholar, Science Direct, and the Cochrane Library were systematically searched. All observational studies reporting cervical cancer screening utilization and/ or its predictors in Ethiopia were included. Two authors independently extracted all necessary data using a standardized data extraction format. Quality assessment criteria for prevalence studies were adapted from the Newcastle Ottawa quality assessment scale. The Cochrane Q test statistics and I 2 test were used to assess the heterogeneity of studies. A random effects model of analysis was used to estimate the pooled prevalence of cervical cancer screening utilization and factors associated with it with the 95% confidence intervals (CIs). From 850 potentially relevant articles, twenty-five studies with a total of 18,067 eligible women were included in this study. The pooled national cervical cancer screening utilization was 14.79% (95% CI: 11.75, 17.83). The highest utilization of cervical cancer screening (18.59%) was observed in Southern Nations Nationalities and Peoples’ region (SNNPR), and lowest was in Amhara region (13.62%). The sub-group analysis showed that the pooled cervical cancer screening was highest among HIV positive women (20.71%). This meta-analysis also showed that absence of women’s formal education reduces cervical cancer screening utilization by 67% [POR = 0.33, 95% CI: 0.23, 0.46]. Women who had good knowledge towards cervical screening [POR = 3.01, 95%CI: 2.2.6, 4.00], perceived susceptibility to cervical cancer [POR = 4.9, 95% CI: 3.67, 6.54], severity to cervical cancer [POR = 6.57, 95% CI: 3.99, 10.8] and those with a history of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) [POR = 5.39, 95% CI: 1.41, 20.58] were more likely to utilize cervical cancer screening. Additionally, the major barriers of cervical cancer screening utilization were considering oneself as healthy (48.97%) and lack of information on cervical cancer screening (34.34%).

Conclusions

This meta-analysis found that the percentage of cervical cancer screening among eligible women was much lower than the WHO recommendations. Only one in every seven women utilized cervical cancer screening in Ethiopia. There were significant variations in the cervical cancer screening based on geographical regions and characteristics of women. Educational status, knowledge towards cervical cancer screening, perceived susceptibility and severity to cervical cancer and history of STIs significantly increased the uptake of screening practice. Therefore, women empowerment, improving knowledge towards cervical cancer screening, enhancing perceived susceptibility and severity to cancer and identifying previous history of women are essential strategies to improve cervical cancer screening practice.

Despite a remarkable progress in the reduction of maternal mortality, cervical cancer is the second most commonly diagnosed cancer and the leading cause of cancer related death among African women [ 1 ]. There were approximately 236,000 deaths from cervical cancer worldwide and it was the most common cancer in east and middle Africa [ 2 , 3 ]. About 90% of cases and 85% of these deaths have occurred in Low and Middle-Income Countries (LMICs); the highest has occurred in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) and approximately 311,000 women died from cervical cancer [ 2 ]. The incidence, the death rate and morbidities associated with cervical cancer significantly varies across the world; higher in the developing nations compared to the developed countries [ 4 ]. The high burden of cervical cancer is mainly due to the early onset of sexual intercourse, multiple sexual partners, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, history of sexually transmitted infections (STIs), human papilloma virus (HPV) infection, cigarette smoking, limited resources for early detection and poor HPV vaccination coverage [ 5 , 6 ].

Almost all of the maternal deaths associated with cervical cancer could be prevented if early and effective interventions mechanisms to cervical cancer control were available to all women. In particular, a comprehensive approach such as prevention, early diagnosis, effective screening and treatment programmes of pre-cervical lesions are essential for prevention of cervical cancer [ 7 ]. Visual inspection with Acetic Acid (VIA) and Visual Inspection with Lugol’s Iodine (VILI) are commonly used in low-resource settings [ 6 ]. VIA combined with the immediate treatment of women who tested positive at the first visit was cost saving and was the next most effective strategy, with a 26% decrease in the incidence of CC, further reduce mortality due to CC. A large-cluster randomized trial from rural India showed that a single round of HPV screening could reduce the incidence and mortality from CC of approximately 50% [ 8 ].

The guidelines of the World Health Organization (WHO), the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) and the American Cancer Society (ACS) recommends that all eligible women should have cervical cancer screening at least once every three years [ 9 ]. Ethiopia adopted WHO’s recommendation that woman aged 30 and above should begin screening for cervical cancer at least one to three years of age with a see- and -treat approach. However, sexually active and HIV-positive women (start screening at HIV diagnosis) are suggested to be screened every 3 years regardless of their age [ 10 ]. The prevalence of cervical cancer screening is much higher at the Western countries than SSA [ 11 , 12 ]; 85.0% in the United States, 78.6% in the United Kingdom [ 13 ], and ranges from 2% in Ethiopia, 6% in Kenya [ 14 ], to 8% in Nigeria [ 15 ]. The lower rate of cervical cancer screening programme at LMICs may be related to the complexity of the screening process and the common inherent barriers in the setting such as poverty, limited access to information, lack of knowledge of cervical cancer, lack of healthcare infrastructure required, lack of trained practitioners and the absence of sustained prevention programmes [ 16 ].

The government of Ethiopia launched a cervical cancer screening service and has given more emphasis on programs focusing on the early detection of cervical cancer using advocacy efforts by different stakeholders such as academia, professionals, media and partners. However, the prevalence of cervical cancer remains a major problem, and it is one of the leading causes of morbidity and mortality among women in the country [ 17 , 18 ]. Evidence show success of cervical screening initiatives depend on high participation of the target population, which in turn is determined by the women’s knowledge, perceptions, health orientations and other socio-cultural issues. It is also affected by factors including early marriage, early sexual practice, delivery of the first baby before the age of 20, multiple sexual partners and low socio economic status. Therefore, addressing the different barriers for poor utilization of cervical cancer screening is essential component of intervention. Although, there were previous pocket studies conducted on these issues in Ethiopia, the studies showed fragmented, inconsistent and inconclusive findings. Even the studies were fragmented in different specific population characteristics like among HIV positive women and reproductive age women. Therefore, this systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to estimate the pooled cervical cancer screening utilization and its predictors among all eligible women in Ethiopia. It also aimed to address the common barriers of cervical cancer screening.

Registration of systematic review, data sources and search strategies

The purpose of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to estimate the pooled utilization level of cervical cancer screening and its predictors among women of reproductive-aged in Ethiopia. The protocol has been registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Review (PROSPERO), the University of York Center for Reviews and Dissemination ( https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/ ), registration number CRD42019119626 . The findings of this review have been reported as recommended by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA-P) 2009 statement checklist [ 19 ] ( S1 Table ). All published articles were searched from major international databases like PubMed, Cochrane Library, Psych Info, Scopus, CINAHL, Web of Science, Science Direct, Google Scholar and African Journals Online. Additionally, Google hand searches were used mainly for unpublished studies. A search was also made for the reference list of studies already identified in order to retrieve additional articles. The Population, Exposure, Comparison and Outcomes (PECO) search formula was used to retrieve articles.

All eligible women for cervical cancer screening Ethiopia were the population of interest for this study. The outcome of interest was the utilization of cervical cancer screening among women. The predictor variables of cervical cancer screening utilization included in this study were age of women, educational status, and occupational status, knowledge of cervical cancer screening, perceived susceptibility and severity to cervical cancer and history of sexually transmitted infections. Comparisons were defined for each predictor based on the reported reference group for each predictor in each respective variable.

For each of the selected components of PECO, electronic databases were searched using the keyword search and the medical subject heading [MeSH] words. The keywords include “utilization, uptake, cervical cancer, screening, and women of reproductive age as well as Ethiopia”. The search terms were combined by the Boolean operators "OR" and "AND. The specific searching detail in PubMed was putted in S1 Appendix .

Eligibility criteria and study selection

This review included studies that reported either the use of cervical cancer screening or the cervical cancer screening predictors in Ethiopia. All published and unpublished studies through April 7, 2020 and reported in English language were retrieved to assess eligibility for inclusion in this review. However, this review excluded studies that were case reports of populations, surveillance data (demographic health survey), and abstracts of conferences, articles without full access and the outcome of interest not reported. The article selection underwent several steps. Two reviewers (MD and TE) evaluated the retrieved articles for inclusion using their title, abstract and full text review. Any disagreement during the selection process between the reviewers was resolved by consensus. Full texts of selected articles were then evaluated using the prior eligibility. During the encounter of duplication; only the full-text article was retained.

Quality assessment and data collection

The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) quality assessment tool was used to assess the quality of the included studies. The tool contains three components- selection of the study groups, comparability of the study groups, and ascertainment of exposure or outcome [ 20 ]. The main component of the tool was graded from five stars and mainly emphasized on the methodological quality of each primary study. The other component of the tool graded from two stars and mainly concerned with the comparability of each study. The last component of the tool was graded from three stars and was used to evaluate the results and statistical analysis of each original study. The NOS included three categorical criteria with a maximum score of 9 points. The quality of each study was assessed using the following score algorithms: ≥7 points were considered as “good”, 4 to 6 points were considered as “moderate”, and ≤ 3 point was considered as “poor” quality studies. In order to improve the validity of this systematic review result, only primary studies of fair to good quality have been included. The two reviewers (MD and TE) independently assessed articles for overall study quality and extracted data using a standardized data extraction format. The data extraction format included primary author, year of publication, region of the study, sample size, prevalence, and the selected predictors of cervical cancer screening utilization.

Publication bias and statistical analysis

The publication bias was assessed using the Egger’s [ 21 ] and Begg’s [ 22 ] tests with a p-value of less than 0.05. The I 2 statistic was used to assess heterogeneity between studies and a p-value of less than 0.05 was used to detect heterogeneity. As a result of the presence of heterogeneity, a random-effects model was used as a method of analysis [ 23 ]. Data were extracted in Microsoft Excel and exported to Stata version 11 for analysis. Subgroup analysis was conducted by geographic region, population’s characteristics and design or type of study. Moreover, a meta-regression model based on sample size and year of publication was used to identify the sources of random variations in the included studies. The effect of selected determinant variables was analyzed using separate categories of meta-analysis [ 24 ]. The findings of the meta-analysis were presented using forest plots and Odds Ratio (OR) with its 95% Confidence intervals (CI). In addition, we conducted a sensitivity analysis to assess whether the pooled prevalence estimates were influenced by individual studies.

Study identification and characteristics of included studies

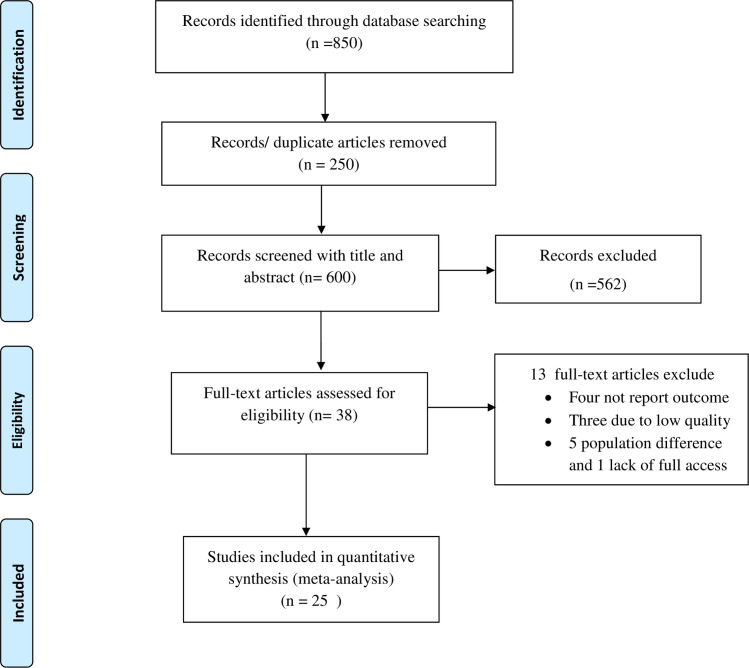

This systematic review and meta-analysis included both published and unpublished studies on the use of cervical cancer screening in Ethiopia. A total of 850 articles were found from the review. Of these, 250 duplicated records were removed and 581 articles were excluded by screening using their titles and abstracts. Subsequently, a total of 38 full-text papers were assessed for eligibility on the basis of the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Thus, four studies were excluded due to lack of the outcome of interest [ 25 – 30 ], three due to low quality [ 31 – 33 ], five due to difference in the study population [ 34 – 39 ] and only one study was excluded due to lack of access to the full text [ 40 ]. Finally, 25 studies were included in the final quantitative meta-analysis ( Fig 1 ).

Fig 1. PRISMA flow diagram of cervical cancer screening utilization in Ethiopia.

All of the included studies were cross-sectional. From this, twelve studies were facility- based cross sectional studies (FBCS) and thirteen were community- based cross-sectional studies (CBCS). The review was conducted among 18,067 women to estimate the pooled prevalence of cervical cancer screening. Publication of articles was between 2016 and 2020. The largest sample size was 5,823 women in a national level study [ 41 ] and the smallest sample was 250 women from a study conducted in Oromia region [ 42 ]. All studies were conducted in five geographic regions of Ethiopia. Four studies (16%) were from Addis Ababa [ 43 – 46 ], nine (36%) were from Amhara [ 47 – 55 ], four (16%) were from Southern Nations, Nationalities and Peoples Representative (SNNPR) [ 56 – 60 ], four (16%) were from Oromia [ 42 , 61 – 63 ], two (8%) were from Tigray [ 64 , 65 ], and the remaining one study [ 41 ] was a national- level study. Twelve studies were conducted among eligible women with no specific characteristics of their HIV status [ 44 , 47 ], five studies on HIV-positive women [ 43 , 48 , 53 , 61 , 63 ], four studies among healthcare workers [ 59 , 63 , 65 , 66 ] and the remaining one study [ 51 ] was conducted among women who were commercial sex workers ( Table 1 ).

Table 1. Characteristics of the included studies in the meta-analysis, Ethiopia.

AA: Addis Ababa; CSWs: Commercial sex workers.

CBCS: community based cross-sectional study; FBCS: facility based cross-sectional study.

Meta-analysis of cervical cancer screening utilization in Ethiopia

The highest cervical cancer screening utilization was observed in SNNPR, a study conducted at ART health facilities of Hawassa, 40% [ 57 ] and Wolayita hospitals, 22.9% [ 60 ]. Whereas, the lowest was 2.9% in a national level study [ 41 ] and 5.4% from a study conducted in Amhara region [ 54 ].

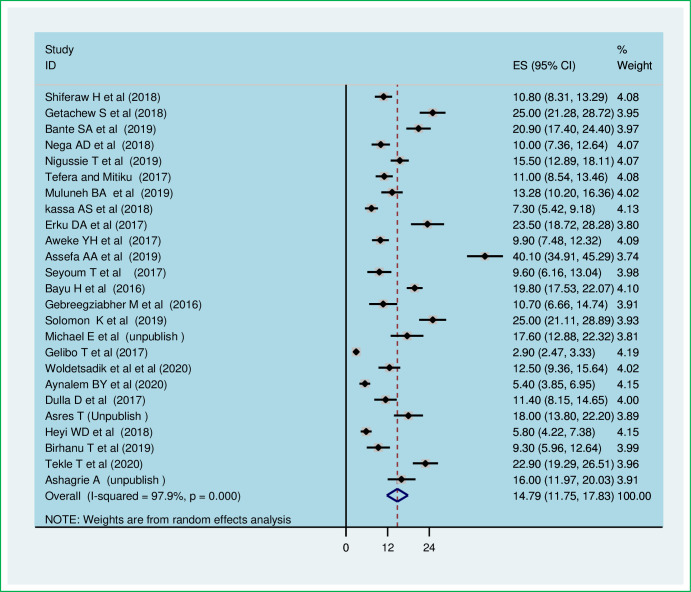

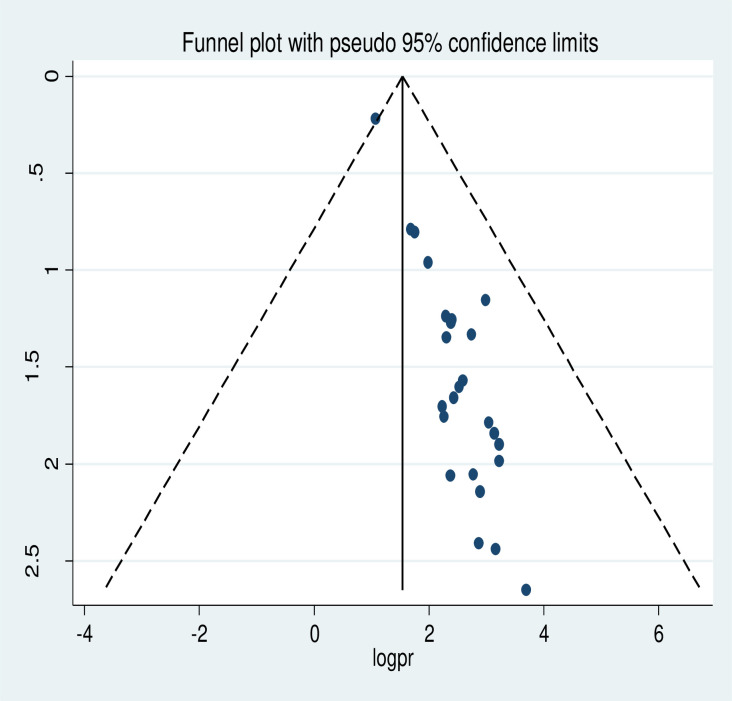

The meta-analysis of twenty-five studies showed that the pooled national level of cervical cancer screening utilization was 14.79% (95% CI: 11.75, 17.83). A random-effect model of analysis was used due to significant heterogeneity ( I 2 = 97.9%, p-value <0.05) ( Fig 2 ). Publication bias was assessed using Eggers test and it was statistically significant, p-value less than 0.0001. To account for publication bias, the duval and trimmed full analysis was performed. The univariate meta-regression model was also used to identify possible sources of heterogeneity using different covariates like year of publication and sample size. However, none of these variables were found to be statistically significant, p-value > 0.05. Moreover, the sensitivity analysis using a random-effects model showed that no single study had unduly influenced the overall estimate of the use of cervical cancer screening among Ethiopian women ( S1 Fig ). The funnel plot also showed that there was symmetrical distribution ( Fig 3 ).

Fig 2. The pooled utilization of cervical cancer screening among women in Ethiopia.

Fig 3. Funnel plot of the prevalence of cervical cancer screening utilization in Ethiopia.

Subgroup analysis

The subgroup analysis was conducted based on region of studies, the study design and women’s characteristics. Therefore, this random effect meta-analysis based on the geographic region revealed that the highest cervical cancer screening utilization was observed in the SNNPR, 18.59 (95% CI: 9.65, 27.53) followed by Oromia region, 16.00% (95% CI: 16.00% (95% CI: 6.31, 25.7) and lowest occurred in Amhara region, 13.62% (95% CI: 9.92, 17.32) ( Table 2 ). In addition, the pooled subgroup analysis showed that cervical cancer screening was highest in studies that were institution- based cross-sectional studies, 17.54% (95% CI: 13.16, 21.93). The highest cervical cancer screening was among HIV- positive women, 20.71% (95% CI: 12.8, 28.63) and the lowest was among reproductive age women, 11.54% (95% CI: 8.00, 15.05) ( Table 2 ).

Table 2. Sub-group analysis of cervical cancer screening utilization in Ethiopia: A meta-analysis.

Predictors of cervical cancer screening utilization, association of educational status and utilization of cervical cancer screening.

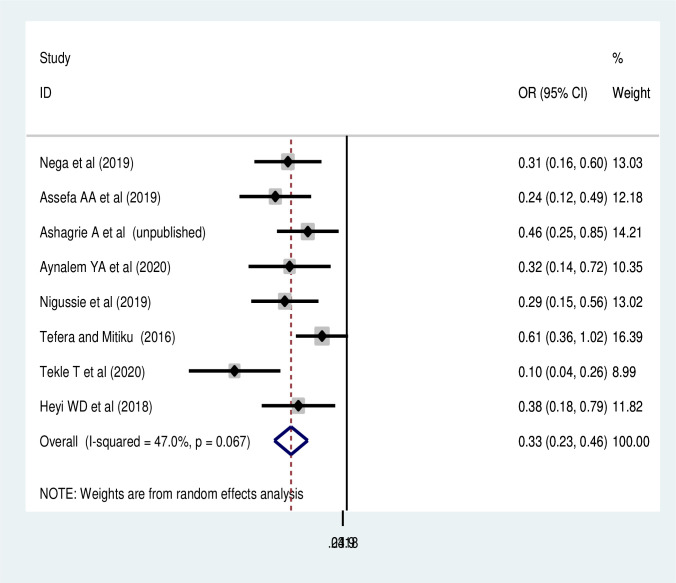

In regard to the social inequities, the effects of three predictors on cervical cancer screening utilization were estimated. Thus, age of women and occupational status were not significantly associated with cervical cancer screening utilization ( S2 and S3 Figs). While, women’s educational status was significantly associated with utilization of cervical cancer screening. Accordingly, the pooled random effect of eight studies [ 48 – 50 , 54 , 57 , 62 , 63 , 60 ] found that women who have no formal education were 66% (POR:0.33, 95% CI: 0.23,0.46) times less likely to utilize cervical cancer screening than those who attended any formal education ( Fig 4 ).

Fig 4. Association of educational status with cervical cancer screening in Ethiopia.

Association of knowledge and perception of cancer and screening utilization

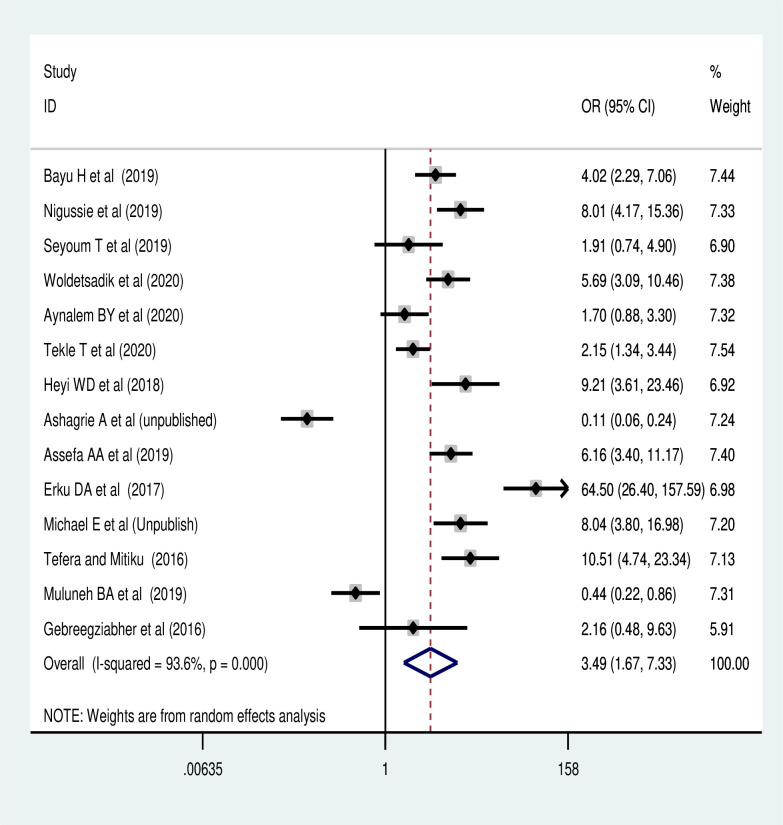

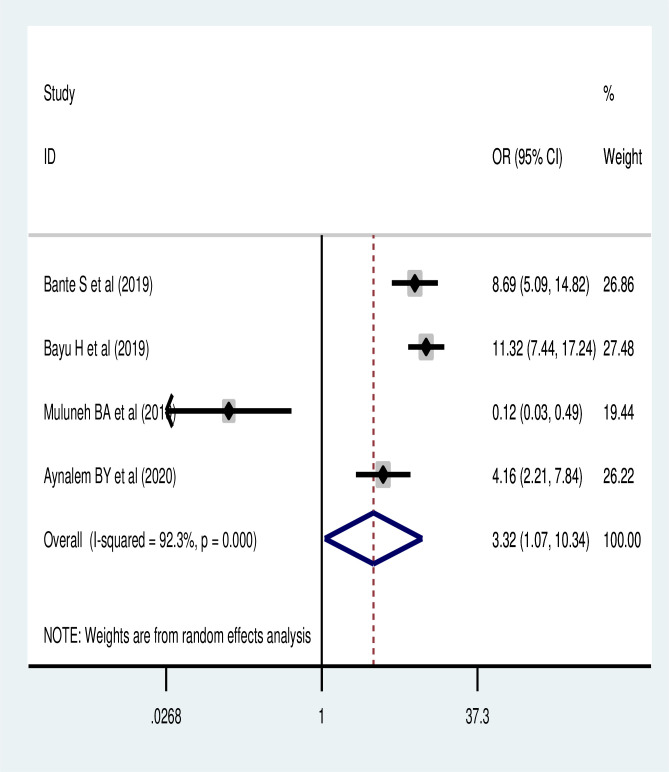

The meta-analysis of 14 studies revealed [ 42 , 45 , 49 – 51 , 53 , 54 , 57 , 58 , 60 , 62 – 65 ] that women’s knowledge of cervical cancer screening uptake was the commonest predictor of screening utilization. Women who had good knowledge of cervical cancer screening reuptake were 3.97 times (POR: 3.49, 95% CI: 1.67, 7.33) more likely to have cervical cancer screening than women who had poor knowledge ( Fig 5 ).

Fig 5. Association of knowledge of the screening with cervical cancer screening utilization.

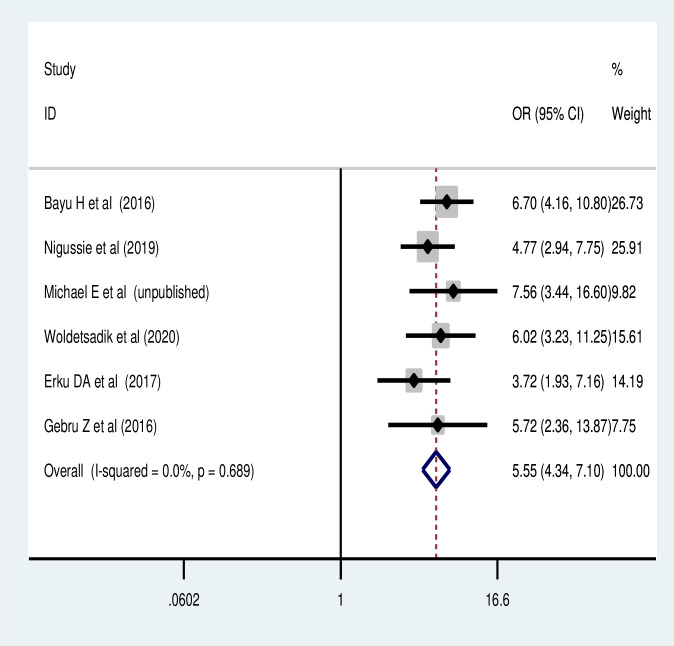

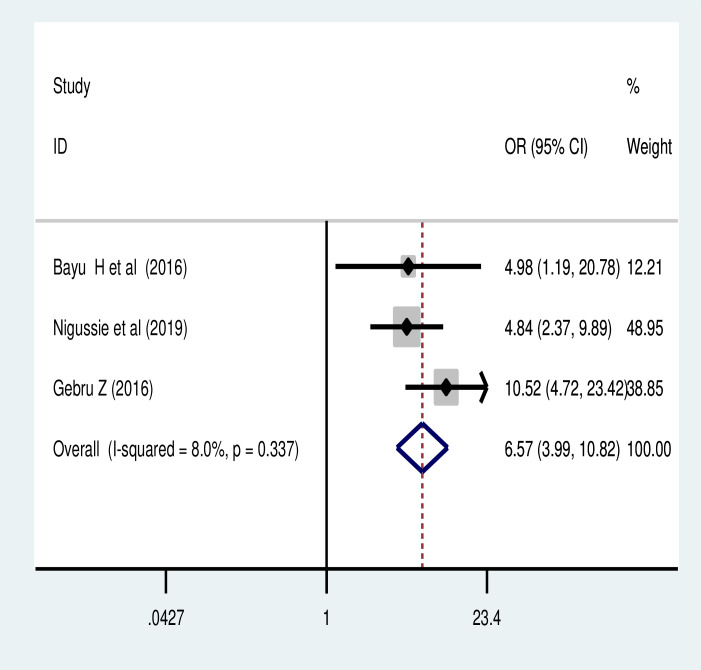

The pooled effect of six studies [ 33 , 42 , 45 , 49 , 53 , 64 ] also revealed that the perceived susceptibility to cervical cancer was another major predictor of cervical cancer screening utilization in Ethiopia. Women who had perceived susceptibility to cervical cancer were 5.5 times more likely to reuptake cervical cancer screening than their counterparts (POR = 5.54, 95% CI: 4.28, 7.16) ( Fig 6 ). Similarly, women who had perceived severity of cervical cancer were more likely to utilize cervical cancer screening (POR = 6.57, 95% CI: 3.99, 10.82) ( Fig 7 ).

Fig 6. Association of perceived susceptibility to cervical cancer with cervical cancer screening.