The Savvy Scientist

Experiences of a London PhD student and beyond

My Complete Guide to Academic Peer Review: Example Comments & How to Make Paper Revisions

Once you’ve submitted your paper to an academic journal you’re in the nerve-racking position of waiting to hear back about the fate of your work. In this post we’ll cover everything from potential responses you could receive from the editor and example peer review comments through to how to submit revisions.

My first first-author paper was reviewed by five (yes 5!) reviewers and since then I’ve published several others papers, so now I want to share the insights I’ve gained which will hopefully help you out!

This post is part of my series to help with writing and publishing your first academic journal paper. You can find the whole series here: Writing an academic journal paper .

The Peer Review Process

When you submit a paper to a journal, the first thing that will happen is one of the editorial team will do an initial assessment of whether or not the article is of interest. They may decide for a number of reasons that the article isn’t suitable for the journal and may reject the submission before even sending it out to reviewers.

If this happens hopefully they’ll have let you know quickly so that you can move on and make a start targeting a different journal instead.

Handy way to check the status – Sign in to the journal’s submission website and have a look at the status of your journal article online. If you can see that the article is under review then you’ve passed that first hurdle!

When your paper is under peer review, the journal will have set out a framework to help the reviewers assess your work. Generally they’ll be deciding whether the work is to a high enough standard.

Interested in reading about what reviewers are looking for? Check out my post on being a reviewer for the first time. Peer-Reviewing Journal Articles: Should You Do It? Sharing What I Learned From My First Experiences .

Once the reviewers have made their assessments, they’ll return their comments and suggestions to the editor who will then decide how the article should proceed.

How Many People Review Each Paper?

The editor ideally wants a clear decision from the reviewers as to whether the paper should be accepted or rejected. If there is no consensus among the reviewers then the editor may send your paper out to more reviewers to better judge whether or not to accept the paper.

If you’ve got a lot of reviewers on your paper it isn’t necessarily that the reviewers disagreed about accepting your paper.

You can also end up with lots of reviewers in the following circumstance:

- The editor asks a certain academic to review the paper but doesn’t get a response from them

- The editor asks another academic to step in

- The initial reviewer then responds

Next thing you know your work is being scrutinised by extra pairs of eyes!

As mentioned in the intro, my first paper ended up with five reviewers!

Potential Journal Responses

Assuming that the paper passes the editor’s initial evaluation and is sent out for peer-review, here are the potential decisions you may receive:

- Reject the paper. Sadly the editor and reviewers decided against publishing your work. Hopefully they’ll have included feedback which you can incorporate into your submission to another journal. I’ve had some rejections and the reviewer comments were genuinely useful.

- Accept the paper with major revisions . Good news: with some more work your paper could get published. If you make all the changes that the reviewers suggest, and they’re happy with your responses, then it should get accepted. Some people see major revisions as a disappointment but it doesn’t have to be.

- Accept the paper with minor revisions. This is like getting a major revisions response but better! Generally minor revisions can be addressed quickly and often come down to clarifying things for the reviewers: rewording, addressing minor concerns etc and don’t require any more experiments or analysis. You stand a really good chance of getting the paper published if you’ve been given a minor revisions result.

- Accept the paper with no revisions . I’m not sure that this ever really happens, but it is potentially possible if the reviewers are already completely happy with your paper!

Keen to know more about academic publishing? My series on publishing is now available as a free eBook. It includes my experiences being a peer reviewer. Click the image below for access.

Example Peer Review Comments & Addressing Reviewer Feedback

If your paper has been accepted but requires revisions, the editor will forward to you the comments and concerns that the reviewers raised. You’ll have to address these points so that the reviewers are satisfied your work is of a publishable standard.

It is extremely important to take this stage seriously. If you don’t do a thorough job then the reviewers won’t recommend that your paper is accepted for publication!

You’ll have to put together a resubmission with your co-authors and there are two crucial things you must do:

- Make revisions to your manuscript based off reviewer comments

- Reply to the reviewers, telling them the changes you’ve made and potentially changes you’ve not made in instances where you disagree with them. Read on to see some example peer review comments and how I replied!

Before making any changes to your actual paper, I suggest having a thorough read through the reviewer comments.

Once you’ve read through the comments you might be keen to dive straight in and make the changes in your paper. Instead, I actually suggest firstly drafting your reply to the reviewers.

Why start with the reply to reviewers? Well in a way it is actually potentially more important than the changes you’re making in the manuscript.

Imagine when a reviewer receives your response to their comments: you want them to be able to read your reply document and be satisfied that their queries have largely been addressed without even having to open the updated draft of your manuscript. If you do a good job with the replies, the reviewers will be better placed to recommend the paper be accepted!

By starting with your reply to the reviewers you’ll also clarify for yourself what changes actually have to be made to the paper.

So let’s now cover how to reply to the reviewers.

1. Replying to Journal Reviewers

It is so important to make sure you do a solid job addressing your reviewers’ feedback in your reply document. If you leave anything unanswered you’re asking for trouble, which in this case means either a rejection or another round of revisions: though some journals only give you one shot! Therefore make sure you’re thorough, not just with making the changes but demonstrating the changes in your replies.

It’s no good putting in the work to revise your paper but not evidence it in your reply to the reviewers!

There may be points that reviewers raise which don’t appear to necessitate making changes to your manuscript, but this is rarely the case. Even for comments or concerns they raise which are already addressed in the paper, clearly those areas could be clarified or highlighted to ensure that future readers don’t get confused.

How to Reply to Journal Reviewers

Some journals will request a certain format for how you should structure a reply to the reviewers. If so this should be included in the email you receive from the journal’s editor. If there are no certain requirements here is what I do:

- Copy and paste all replies into a document.

- Separate out each point they raise onto a separate line. Often they’ll already be nicely numbered but sometimes they actually still raise separate issues in one block of text. I suggest separating it all out so that each query is addressed separately.

- Form your reply for each point that they raise. I start by just jotting down notes for roughly how I’ll respond. Once I’m happy with the key message I’ll write it up into a scripted reply.

- Finally, go through and format it nicely and include line number references for the changes you’ve made in the manuscript.

By the end you’ll have a document that looks something like:

Reviewer 1 Point 1: [Quote the reviewer’s comment] Response 1: [Address point 1 and say what revisions you’ve made to the paper] Point 2: [Quote the reviewer’s comment] Response 2: [Address point 2 and say what revisions you’ve made to the paper] Then repeat this for all comments by all reviewers!

What To Actually Include In Your Reply To Reviewers

For every single point raised by the reviewers, you should do the following:

- Address their concern: Do you agree or disagree with the reviewer’s comment? Either way, make your position clear and justify any differences of opinion. If the reviewer wants more clarity on an issue, provide it. It is really important that you actually address their concerns in your reply. Don’t just say “Thanks, we’ve changed the text”. Actually include everything they want to know in your reply. Yes this means you’ll be repeating things between your reply and the revisions to the paper but that’s fine.

- Reference changes to your manuscript in your reply. Once you’ve answered the reviewer’s question, you must show that you’re actually using this feedback to revise the manuscript. The best way to do this is to refer to where the changes have been made throughout the text. I personally do this by include line references. Make sure you save this right until the end once you’ve finished making changes!

Example Peer Review Comments & Author Replies

In order to understand how this works in practice I’d suggest reading through a few real-life example peer review comments and replies.

The good news is that published papers often now include peer-review records, including the reviewer comments and authors’ replies. So here are two feedback examples from my own papers:

Example Peer Review: Paper 1

Quantifying 3D Strain in Scaffold Implants for Regenerative Medicine, J. Clark et al. 2020 – Available here

This paper was reviewed by two academics and was given major revisions. The journal gave us only 10 days to get them done, which was a bit stressful!

- Reviewer Comments

- My reply to Reviewer 1

- My reply to Reviewer 2

One round of reviews wasn’t enough for Reviewer 2…

- My reply to Reviewer 2 – ROUND 2

Thankfully it was accepted after the second round of review, and actually ended up being selected for this accolade, whatever most notable means?!

Nice to see our recent paper highlighted as one of the most notable articles, great start to the week! Thanks @Materials_mdpi 😀 #openaccess & available here: https://t.co/AKWLcyUtpC @ICBiomechanics @julianrjones @saman_tavana pic.twitter.com/ciOX2vftVL — Jeff Clark (@savvy_scientist) December 7, 2020

Example Peer Review: Paper 2

Exploratory Full-Field Mechanical Analysis across the Osteochondral Tissue—Biomaterial Interface in an Ovine Model, J. Clark et al. 2020 – Available here

This paper was reviewed by three academics and was given minor revisions.

- My reply to Reviewer 3

I’m pleased to say it was accepted after the first round of revisions 🙂

Things To Be Aware Of When Replying To Peer Review Comments

- Generally, try to make a revision to your paper for every comment. No matter what the reviewer’s comment is, you can probably make a change to the paper which will improve your manuscript. For example, if the reviewer seems confused about something, improve the clarity in your paper. If you disagree with the reviewer, include better justification for your choices in the paper. It is far more favourable to take on board the reviewer’s feedback and act on it with actual changes to your draft.

- Organise your responses. Sometimes journals will request the reply to each reviewer is sent in a separate document. Unless they ask for it this way I stick them all together in one document with subheadings eg “Reviewer 1” etc.

- Make sure you address each and every question. If you dodge anything then the reviewer will have a valid reason to reject your resubmission. You don’t need to agree with them on every point but you do need to justify your position.

- Be courteous. No need to go overboard with compliments but stay polite as reviewers are providing constructive feedback. I like to add in “We thank the reviewer for their suggestion” every so often where it genuinely warrants it. Remember that written language doesn’t always carry tone very well, so rather than risk coming off as abrasive if I don’t agree with the reviewer’s suggestion I’d rather be generous with friendliness throughout the reply.

2. How to Make Revisions To Your Paper

Once you’ve drafted your replies to the reviewers, you’ve actually done a lot of the ground work for making changes to the paper. Remember, you are making changes to the paper based off the reviewer comments so you should regularly be referring back to the comments to ensure you’re not getting sidetracked.

Reviewers could request modifications to any part of your paper. You may need to collect more data, do more analysis, reformat some figures, add in more references or discussion or any number of other revisions! So I can’t really help with everything, even so here is some general advice:

- Use tracked-changes. This is so important. The editor and reviewers need to be able to see every single change you’ve made compared to your first submission. Sometimes the journal will want a clean copy too but always start with tracked-changes enabled then just save a clean copy afterwards.

- Be thorough . Try to not leave any opportunity for the reviewers to not recommend your paper to be published. Any chance you have to satisfy their concerns, take it. For example if the reviewers are concerned about sample size and you have the means to include other experiments, consider doing so. If they want to see more justification or references, be thorough. To be clear again, this doesn’t necessarily mean making changes you don’t believe in. If you don’t want to make a change, you can justify your position to the reviewers. Either way, be thorough.

- Use your reply to the reviewers as a guide. In your draft reply to the reviewers you should have already included a lot of details which can be incorporated into the text. If they raised a concern, you should be able to go and find references which address the concern. This reference should appear both in your reply and in the manuscript. As mentioned above I always suggest starting with the reply, then simply adding these details to your manuscript once you know what needs doing.

Putting Together Your Paper Revision Submission

- Once you’ve drafted your reply to the reviewers and revised manuscript, make sure to give sufficient time for your co-authors to give feedback. Also give yourself time afterwards to make changes based off of their feedback. I ideally give a week for the feedback and another few days to make the changes.

- When you’re satisfied that you’ve addressed the reviewer comments, you can think about submitting it. The journal may ask for another letter to the editor, if not I simply add to the top of the reply to reviewers something like:

“Dear [Editor], We are grateful to the reviewer for their positive and constructive comments that have led to an improved manuscript. Here, we address their concerns/suggestions and have tracked changes throughout the revised manuscript.”

Once you’re ready to submit:

- Double check that you’ve done everything that the editor requested in their email

- Double check that the file names and formats are as required

- Triple check you’ve addressed the reviewer comments adequately

- Click submit and bask in relief!

You won’t always get the paper accepted, but if you’re thorough and present your revisions clearly then you’ll put yourself in a really good position. Remember to try as hard as possible to satisfy the reviewers’ concerns to minimise any opportunity for them to not accept your revisions!

Best of luck!

I really hope that this post has been useful to you and that the example peer review section has given you some ideas for how to respond. I know how daunting it can be to reply to reviewers, and it is really important to try to do a good job and give yourself the best chances of success. If you’d like to read other posts in my academic publishing series you can find them here:

Blog post series: Writing an academic journal paper

Subscribe below to stay up to date with new posts in the academic publishing series and other PhD content.

Share this:

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

Related Posts

How to Build a LinkedIn Student Profile

18th October 2024 18th October 2024

How to Plan a Research Visit

13th September 2024 13th September 2024

The Five Most Powerful Lessons I Learned During My PhD

8th August 2024 8th August 2024

2 Comments on “My Complete Guide to Academic Peer Review: Example Comments & How to Make Paper Revisions”

Excellent article! Thank you for the inspiration!

No worries at all, thanks for your kind comment!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Privacy Overview

When you choose to publish with PLOS, your research makes an impact. Make your work accessible to all, without restrictions, and accelerate scientific discovery with options like preprints and published peer review that make your work more Open.

- PLOS Biology

- PLOS Climate

- PLOS Complex Systems

- PLOS Computational Biology

- PLOS Digital Health

- PLOS Genetics

- PLOS Global Public Health

- PLOS Medicine

- PLOS Mental Health

- PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases

- PLOS Pathogens

- PLOS Sustainability and Transformation

- PLOS Collections

How to Write a Peer Review

When you write a peer review for a manuscript, what should you include in your comments? What should you leave out? And how should the review be formatted?

This guide provides quick tips for writing and organizing your reviewer report.

Review Outline

Use an outline for your reviewer report so it’s easy for the editors and author to follow. This will also help you keep your comments organized.

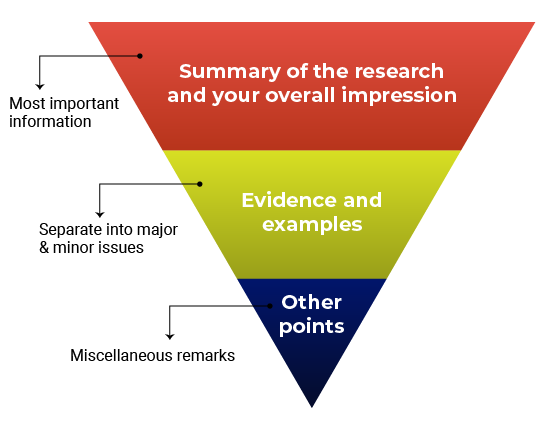

Think about structuring your review like an inverted pyramid. Put the most important information at the top, followed by details and examples in the center, and any additional points at the very bottom.

Here’s how your outline might look:

1. Summary of the research and your overall impression

In your own words, summarize what the manuscript claims to report. This shows the editor how you interpreted the manuscript and will highlight any major differences in perspective between you and the other reviewers. Give an overview of the manuscript’s strengths and weaknesses. Think about this as your “take-home” message for the editors. End this section with your recommended course of action.

2. Discussion of specific areas for improvement

It’s helpful to divide this section into two parts: one for major issues and one for minor issues. Within each section, you can talk about the biggest issues first or go systematically figure-by-figure or claim-by-claim. Number each item so that your points are easy to follow (this will also make it easier for the authors to respond to each point). Refer to specific lines, pages, sections, or figure and table numbers so the authors (and editors) know exactly what you’re talking about.

Major vs. minor issues

What’s the difference between a major and minor issue? Major issues should consist of the essential points the authors need to address before the manuscript can proceed. Make sure you focus on what is fundamental for the current study . In other words, it’s not helpful to recommend additional work that would be considered the “next step” in the study. Minor issues are still important but typically will not affect the overall conclusions of the manuscript. Here are some examples of what would might go in the “minor” category:

- Missing references (but depending on what is missing, this could also be a major issue)

- Technical clarifications (e.g., the authors should clarify how a reagent works)

- Data presentation (e.g., the authors should present p-values differently)

- Typos, spelling, grammar, and phrasing issues

3. Any other points

Confidential comments for the editors.

Some journals have a space for reviewers to enter confidential comments about the manuscript. Use this space to mention concerns about the submission that you’d want the editors to consider before sharing your feedback with the authors, such as concerns about ethical guidelines or language quality. Any serious issues should be raised directly and immediately with the journal as well.

This section is also where you will disclose any potentially competing interests, and mention whether you’re willing to look at a revised version of the manuscript.

Do not use this space to critique the manuscript, since comments entered here will not be passed along to the authors. If you’re not sure what should go in the confidential comments, read the reviewer instructions or check with the journal first before submitting your review. If you are reviewing for a journal that does not offer a space for confidential comments, consider writing to the editorial office directly with your concerns.

Get this outline in a template

Giving Feedback

Giving feedback is hard. Giving effective feedback can be even more challenging. Remember that your ultimate goal is to discuss what the authors would need to do in order to qualify for publication. The point is not to nitpick every piece of the manuscript. Your focus should be on providing constructive and critical feedback that the authors can use to improve their study.

If you’ve ever had your own work reviewed, you already know that it’s not always easy to receive feedback. Follow the golden rule: Write the type of review you’d want to receive if you were the author. Even if you decide not to identify yourself in the review, you should write comments that you would be comfortable signing your name to.

In your comments, use phrases like “ the authors’ discussion of X” instead of “ your discussion of X .” This will depersonalize the feedback and keep the focus on the manuscript instead of the authors.

General guidelines for effective feedback

- Justify your recommendation with concrete evidence and specific examples.

- Be specific so the authors know what they need to do to improve.

- Be thorough. This might be the only time you read the manuscript.

- Be professional and respectful. The authors will be reading these comments too.

- Remember to say what you liked about the manuscript!

Don’t

- Recommend additional experiments or unnecessary elements that are out of scope for the study or for the journal criteria.

- Tell the authors exactly how to revise their manuscript—you don’t need to do their work for them.

- Use the review to promote your own research or hypotheses.

- Focus on typos and grammar. If the manuscript needs significant editing for language and writing quality, just mention this in your comments.

- Submit your review without proofreading it and checking everything one more time.

Before and After: Sample Reviewer Comments

Keeping in mind the guidelines above, how do you put your thoughts into words? Here are some sample “before” and “after” reviewer comments

✗ Before

“The authors appear to have no idea what they are talking about. I don’t think they have read any of the literature on this topic.”

✓ After

“The study fails to address how the findings relate to previous research in this area. The authors should rewrite their Introduction and Discussion to reference the related literature, especially recently published work such as Darwin et al.”

“The writing is so bad, it is practically unreadable. I could barely bring myself to finish it.”

“While the study appears to be sound, the language is unclear, making it difficult to follow. I advise the authors work with a writing coach or copyeditor to improve the flow and readability of the text.”

“It’s obvious that this type of experiment should have been included. I have no idea why the authors didn’t use it. This is a big mistake.”

“The authors are off to a good start, however, this study requires additional experiments, particularly [type of experiment]. Alternatively, the authors should include more information that clarifies and justifies their choice of methods.”

Suggested Language for Tricky Situations

You might find yourself in a situation where you’re not sure how to explain the problem or provide feedback in a constructive and respectful way. Here is some suggested language for common issues you might experience.

What you think : The manuscript is fatally flawed. What you could say: “The study does not appear to be sound” or “the authors have missed something crucial”.

What you think : You don’t completely understand the manuscript. What you could say : “The authors should clarify the following sections to avoid confusion…”

What you think : The technical details don’t make sense. What you could say : “The technical details should be expanded and clarified to ensure that readers understand exactly what the researchers studied.”

What you think: The writing is terrible. What you could say : “The authors should revise the language to improve readability.”

What you think : The authors have over-interpreted the findings. What you could say : “The authors aim to demonstrate [XYZ], however, the data does not fully support this conclusion. Specifically…”

What does a good review look like?

Check out the peer review examples at F1000 Research to see how other reviewers write up their reports and give constructive feedback to authors.

Time to Submit the Review!

Be sure you turn in your report on time. Need an extension? Tell the journal so that they know what to expect. If you need a lot of extra time, the journal might need to contact other reviewers or notify the author about the delay.

Tip: Building a relationship with an editor

You’ll be more likely to be asked to review again if you provide high-quality feedback and if you turn in the review on time. Especially if it’s your first review for a journal, it’s important to show that you are reliable. Prove yourself once and you’ll get asked to review again!

- Getting started as a reviewer

- Responding to an invitation

- Reading a manuscript

- Writing a peer review

The contents of the Peer Review Center are also available as a live, interactive training session, complete with slides, talking points, and activities. …

The contents of the Writing Center are also available as a live, interactive training session, complete with slides, talking points, and activities. …

There’s a lot to consider when deciding where to submit your work. Learn how to choose a journal that will help your study reach its audience, while reflecting your values as a researcher…

- Peer Review System

- Production Service

- OA Publishing Platform

- Law Review System

- Why Scholastica?

- Customer Stories

- eBooks, Guides & More

- Schedule a demo

- Law Reviews

- Innovations In Academia

- New Features

Subscribe to receive posts by email

- Legal Scholarship

- Peer Review/Publishing

- I agree to the data use terms outlined in Scholastica's Privacy Policy Must agree to privacy policy.

How to Write Constructive Peer Review Comments: Tips every journal should give referees

Like the art of tightrope walking, writing helpful peer review comments requires honing the ability to traverse many fine lines.

Referees have to strike a balance between being too critical or too careful, too specific or too vague, too conclusive or too open-ended — and the list goes on. Regardless of the stage of a scholar’s career, learning how to write consistently constructive peer review comments takes time and practice.

Most scholars embark on peer review with little to no formal training. So a bit of guidance from journals before taking on assignments is often welcome and can make a big difference in review quality. In this blog post, we’re rounding up 7 tips journals can give referees to help them conduct solid peer reviews and deliver feedback effectively.

You can incorporate these tips into your journal reviewer guidelines and any training materials you prepare, or feel free to link reviewers straight to this blog post!

Take steps to avoid decision fatigue

Did you know that some sources suggest adults make upwards of 35,000 decisions per day ? Hard to believe, right?!

Whether that stat is indeed the norm, there’s no question that we humans make MANY choices on the regular, from what to wear and what route to take to work to avoid construction to which emails to respond to first and how to go about that really tricky research project in the midst of tackling usual tasks, meetings — and, well, everything else. And that’s all likely before 10 AM!

In his blog post “ How to Peer Review ,” Dr. Matthew Might, Professor in the Department of Medicine and Director of the Hugh Kaul Precision Medicine Institute at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, explained that over time the compounding mental strain of so much deliberation can result in a phenomenon known as decision fatigue . Decision fatigue is a deterioration in decision-making quality, which for busy peer reviewers can lead to writing less than articulate comments at best and missing critical points at worst.

In order to avoid decision fatigue, Might said scholars should try to work on peer reviews early in the day before they become bogged down with other matters. Additionally, he advises referees to work on no more than one review at a time when possible, or within one sitting at least, and to avoid reviewing when they feel tired or hungry. Taking steps to prevent decision fatigue can help scholars produce higher quality comments and, ultimately, write reviews faster because they’ll be working on them at times when they’re likely to be more focused and productive.

Of course, referees won’t always be able to follow every one of the above recommendations all of the time, nor will journal editors know if they have. But, it’s worth it for editors to remind reviewers to take decision fatigue into account before accepting and starting assignments.

Be cognizant of conscious and unconscious biases

Another decision-making factor that can cloud peer reviewers’ judgment that all editors should be hyper-attuned to is conscious and unconscious biases. Journal ethical guidelines are, of course, the first line of defense for preventing explicit biases. Every journal should have conflict of interest policies on when and how to disclose potential competing interests (e.g., financial ties, academic commitments, personal relationships) that could influence reviewers’ (as well as editors’ and authors’) level of objectivity in the publication process. The Committee on Publication Ethics offers many helpful guides for developing conflict of interest / competing interest statements, and medical journals can find a “summary of key elements for peer-reviewed medical journal’s conflict of interest policies” from The World Association of Medical Editors (WAME) here .

But what about unconscious biases that could have potentially insidious impacts on peer reviews?

Journals can help curb implicit bias by following double-anonymized peer review processes. Though, as the editors of Clinical and Translational Gastroenterology acknowledged in an announcement about their decision to move to double-anonymized peer review, even when all parties’ identities are concealed “unintentional exposure of author or institution identity is sometimes unavoidable, such as in small, specialized fields or subsequent to early sharing of data at conferences.”

Truly tackling unconscious biases requires getting to their roots, starting with acknowledging that they exist. Journals should remind reviewers to be cognizant of the fact that everyone harbors implicit biases that could impact their decision-making, as IOPScience does here and Cambridge University Press does here and provide tips for spotting and addressing biases. IOP advises reviewers to “focus on facts rather than feelings, slow down your decision making, and consider and reconsider the reasons for your conclusions.” And CUP reminds referees that “rooting your review in evidence from the paper or proposal is crucial in avoiding bias.”

Journals can also offer unconscious bias prevention training or direct referees to available resources such as this recorded Peer Reviewer Unconscious Bias webinar from the American Heart Association.

Null or negative results aren’t a basis for rejection

Speaking of forms of bias that can affect the peer review process, “positive results bias” — or the tendency to want to accept and publish positive results rather than null or negative results — is a common one. In a Royal Society blog post on what makes a good peer review, Head of the Department of Population Health at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, Dr. Rebecca Sear, spoke to how positive results bias can throw a wrench in peer review. Speaking from the perspective of an author, editor, and reviewer, Sear said, “at worst, this distorts science by keeping valuable research out of the literature entirely. It also creates inefficiencies in the system when publishable research has to be submitted to multiple journals before publication, burdening several reviewers and editors with the costs of evaluating the same research. A further problem is that the anonymity typically given to peer reviewers can result in unprofessional behavior being unleashed on authors.”

Journals can help prevent positive results bias by clearly stating that recommendations regarding manuscript decisions should be made on the basis of the quality of the research question, methodology, and perceived accuracy (rather than positivity) of the findings. Remind reviewers (and editors) that null and negative results can also provide valuable and even novel contributions to the literature.

List the negatives and the positives

When it comes time to write peer review comments, some scholars may intentionally or not lean heavily towards giving criticism rather than praise. Of course, peer reviews need to be rigorous, and that requires a critical eye, but it’s important for reviewers to let authors know what they’re doing right also. Otherwise, the author may lose sight of the working parts of their submission and could end up actually making it worse in revisions.

Journals should remind reviewers that their goal is to help authors identify what they are doing correctly as well as where to improve . Reviews shouldn’t be so negative that the author ends up pulling apart their entire manuscript. Additionally, it’s worth reminding reviewers to keep snarky comments to themselves. As Dr. Might noted in his blog, the presence of sarcasm in peer review may nullify any useful feedback provided in the eyes of the author.

Give concrete examples and advice (within scope!)

No author likes hearing that an area of their paper “needs work” without getting context as to why. It’s essential to remind reviewers to back up their comments and opinions with concrete examples and suggestions for improvement and ensure that any recommendations they’re making are within the scope of the journal requirements and research subject matter in question.

Remind reviewers that if they make suggestions for authors to provide additional references, data points, or experiments, they should be within scope and something the reviewer can confirm they would be able (and willing) to do themselves if in the author’s position.

One of the best ways to help train reviewers on how to give constructive feedback is to provide them with real-world examples. These “ Peer Review Examples “ from F1000 are a great starting point.

Another way editors can help reviewers give more concrete commentary is by advising them to log their reactions and responses to a paper as they read it. This can help reviewers avoid making blanket criticisms about an entire work that are, in fact, only applicable to some sections. It may also encourage reviewers to recognize and point out more positives!

Providing reviewers with detailed feedback forms and manuscript assessment checklists is another surefire way to help them stay on track.

Don’t be afraid to seek support

Journals should also remind prospective reviewers that it’s OK to ask for support when working on peer reviews. For example, an early-career researcher might want to seek a mentor to co-author their first review with them or provide general guidance on how to determine whether an experiment was conducted in the best manner possible (keeping manuscript information confidential, of course).

To help new referees get their footing, journals can assist them in identifying mentorship opportunities where applicable and offer peer reviewer training or links to external resources. For example, Taylor & Francis has an “ Excellence in Peer Review “ course, and Sense About Science has a “ Peer Review Nuts and Bolts “ guide.

For journals dealing with specialized subject matter, it’s also critical to be prepared to bring in expert opinions when needed. Editors should let reviewers know not to hesitate to suggest bringing in an expert if they feel it’s necessary.

Follow the Golden Rule

Finally, perhaps the best piece of advice journals can give reviewers is to follow the Golden Rule. You know it, “do unto others as you would have them do unto you.”

In his “How to peer review” guide, Dr. Matthew Might provided a clear barometer for referees to determine if they’ve prepared a thorough and fair review. “Once you’ve completed your review, ask yourself if you would be satisfied with the quality had you received the same for your own work,” he said. “If the answer is no, revise.”

Related Posts

7 Tips if you're thinking about changing journal peer review software

Are you considering changing peer review systems? This blog post overviews seven tips to help you assess your peer review process needs and how to approach a software transition if you decide it's time to make a switch.

New Edition of Academic Journal Management Best Practices: Tales From the Trenches

In this new edition of Academic Journal Management Best Practices: Tales from the Trenches, we round up tips from seasoned publications managers and editors on how to optimize your editorial workflows, attract more quality submissions, and make strategic plans to further your journal goals.

5 Scholarly publishing trends to watch in 2022

Publishing consultant Lettie Conrad and Scholastica's Danielle Padula share the top five scholarly publishing trends they're watching in 2022 and implications for small to mid-sized and independent publishers.

3 Keys to running an effective operational journal audit

Trying to optimize peer review processes while in the throes of daily editorial work isn't easy. That's why it's imperative for journal teams to set aside time for regular operational audits. Here are three tips to help.

The Rise of DIY Open Access Journals: University of Cambridge OA Week Presentation

As part of OA Week 2017, Scholastica had the opportunity to be a part of the University of Cambridge Open Access Week speaking series event Helping Researchers Publish in Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics. Here's a recap of Scholastica CoFounder and CEO Brian Cody's presentation on the rise of DIY OA journal publishing.

Looking back at 2022, and forward to the next 10 years at Scholastica

In our latest blog post, Scholastica CEO and co-founder Brian Cody takes some time to share a recap of 2022 and a sneak peek at what we have planned for the year ahead.