The Elements of Thought

How we think….

The Intellectual Standards

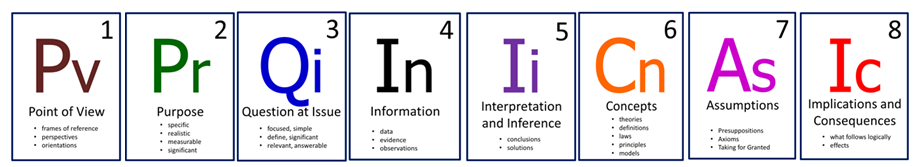

We all have a system to break down how we understand things, how the world looks to us, how we make sense of the world. The ways we think are called the Elements of Thought .

But once we have thought about something, how do we know if we’re right? How do we know if our thinking is any good?

Unfortunately, most of the time we don’t think well. We tend to favor decisions and ideas that favor us, put our own group over other groups. We are…ego-centric and socio-centric. So, we need to force ourselves to look at things the way they truly are. So, to assess the quality of our thinking, we use the Intellectual Standards .

There are nine Intellectual Standards we use to assess thinking: Clarity , Accuracy , Precision , Relevance , Depth , Breadth , Logic , Significance , and Fairness . Let’s check them out one-by-one.

Clarity forces the thinking to be explained well so that it is easy to understand. When thinking is easy to follow, it has Clarity.

Accuracy makes sure that all information is correct and free from error. If the thinking is reliable, then it has Accuracy.

Precision goes one step further than Accuracy. It demands that the words and data used are exact. If no more details could be added, then it has Precision.

Relevance means that everything included is important, that each part makes a difference. If something is focused on what needs to be said, there is Relevance.

Depth makes the argument thorough. It forces us to explore the complexities. If an argument includes all the nuances necessary to make the point, it has Depth.

Breadth demands that additional viewpoints are taken into account. Are all perspectives considered? When all sides of an argument are discussed, then we find Breadth.

Logical means that an argument is reasonable, the thinking is consistent and the conclusions follow from the evidence. When something makes sense step-by-step, then it is Logical.

Significance compels us to include the most important ideas. We don’t want to leave out crucial facts that would help to make a point. When everything that is essential is included, then we find Significance.

Fairness means that the argument is balanced and free from bias. It pushes us to be impartial and evenhanded toward other positions. When an argument is objective, there is Fairness.

There are more Intellectual Standards, but if you use these nine to assess thinking, then you’re on your way to thinking like a pro.

Share this:

3 thoughts on “ the intellectual standards ”.

Pingback: Los 7 estándares universales del pensamiento – Inteligencia artificial 7 semestre

Pingback: What We're Reading and Watching: July 2017 - Center for Critical Thinking

Pingback: Capella University Susan Career Adjustment Goals Paper | Scholarly Script

Comments are closed.

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- Manage subscriptions

Westside Toastmasters is located in Los Angeles and Santa Monica, California

Chapter 7. the standards for thinking.

One of the fundamentals of critical thinking is the ability to assess one's own reasoning. To be good at assessment requires that we consistently take apart our thinking and examine the parts with respect to standards of quality. We do this using criteria based on clarity, accuracy, precision, relevance, depth, breadth, logicalness, and significance. Critical thinkers recognize that, whenever they are reasoning, they reason to some purpose (element of reasoning). Implicit goals are built into their thought processes. But their reasoning is improved when they are clear (intellectual standard) about that purpose or goal. Similarly, to reason well, they need to know that, consciously or unconsciously, they are using information (element of reasoning) in thinking. But their reasoning improves if and when they make sure that the information they are using is accurate (intellectual standard).

Put another way, when we assess our reasoning, we want to know how well we are reasoning. We do not identify the elements of reasoning for the fun of it. Rather, we assess our reasoning using intellectual standards because we realize the negative consequences of failing to do so. In assessing our reasoning, then, we recommend these intellectual standards as minimal:

Logicalness

Significance.

These are not the only intellectual standards a person might use. They are simply among those that are most fundamental. In this respect, the elements of thought are more basic, because the eight elements we have identified are universal - present in all reasoning of all subjects in all cultures. On the one hand, one cannot reason with no information about no question from no point of view with no assumptions. On the other hand, there are a wide variety of intellectual standards from which to choose - such as credibility, predictability, feasibility, and completeness - that we don't use routinely in assessing reasoning.

As critical thinkers, then, we think about our thinking with these kinds of questions in mind: Am I being clear? Accurate? Precise? Relevant? Am I thinking logically? Am I dealing with a matter of significance? Is my thinking justifiable in context? Typically, we apply these standards to one or more elements.

Taking a Deeper Look at Universal Intellectual Standards

Thinking critically requires command of fundamental intellectual standards. Critical thinkers routinely ask questions that apply intellectual standards to thinking. The ultimate goal is for these questions to become so spontaneous in thinking that they form a natural part of our inner voice, guiding us to better and better reasoning. In this section, we focus on the standards and questions that apply across the various facets of your life.

Questions that focus on clarity include:

Could you elaborate on that point?

Could you express that point in another way?

Could you give me an illustration?

Could you give me an example?

Let me state in my own words what I think you just said. Tell me if I am clear about your meaning.

Clarity is a gateway standard. If a statement is unclear, we cannot determine whether it is accurate or relevant. In fact, we cannot tell anything about it because we don't yet know what is being said. For example, the question "What can be done about the education system in America?" is unclear. To adequately address the question, we would need a clearer understanding of what the person asking the question is considering the "problem" to be. A clearer question might be, "What can educators do to ensure that students learn the skills and abilities that help them function successfully on the job and in their daily decision-making?" This question, because of its increased clarity, provides a better guide to thinking. It lays out in a more definitive way the intellectual task at hand.

Questions focusing on making thinking more accurate include:

Is that really true?

How could we check to see if that is accurate?

How could we find out if that is true?

A statement may be clear but not accurate, as in, "Most dogs weigh more than 300 pounds." To be accurate is to represent something in accordance with the way it actually is. People often present or describe things or events in a way that is not in accordance with the way things actually are. People frequently misrepresent or falsely describe things, especially when they have a vested interest in the description. Advertisers often do this to keep a buyer from seeing the weaknesses in a product. If an advertisement states, "Our water is 100% pure" when, in fact, the water contains trace amounts of chemicals such as chlorine and lead, it is inaccurate. If an advertisement says, "this bread contains 100% whole wheat" when the whole wheat has been bleached and enriched and the bread contains many additives, the advertisement is inaccurate.

Good thinkers listen carefully to statements and, when there is reason for skepticism, question whether what they hear is true and accurate. In the same way, they question the extent to which what they read is correct, when asserted as fact. Critical thinking, then, implies a healthy skepticism about public descriptions as to what is and is not fact.

At the same time, because we tend to think from a narrow, self-serving perspective, assessing ideas for accuracy can be difficult. We naturally tend to believe that our thoughts are automatically accurate just because they are ours, and therefore that the thoughts of those who disagree with us are inaccurate. We also fail to question statements that others make that conform to what we already believe, while we tend to question statements that conflict with our views. But as critical thinkers, we force ourselves to accurately assess our own views as well as those of others. We do this even if it means facing deficiencies in our thinking.

In Search of the Facts

One of the most important critical thinking skills is the skill of assessing the accuracy of "factual" claims (someone's assertion that such-and-so is a fact).

In an ad in the New York Times Nov. 29, 1999, p. A15)-->, a coalition of 60 nonprofit organizations accused the World Trade Organization (a coalition of 134 nation states) of operating in secret, undermining democratic institutions and the environment. In the process of doing this, the nonprofit coalition argued that the working class and the poor have not significantly benefited as a result of the last 20 years of rapid expansion of global trade. They alleged, among other things, the following facts:

- "American CEOs are now paid, on average, 419 times more than line workers, and the ratio is increasing."

- "Median hourly wages for workers are down by 10% in the last 10 years."

- "The top 20% of the U.S. population owns 84.6% of the country's wealth."

- "The wealth of the world's 475 billionaires now equals the annual incomes of more than 50% of the world population combined."

Using whatever sources you can find www.turnpoint.org ),--> discuss the probable accuracy of the factual claims. For example, visit the the World Trade Organization website ( www.wto.org ). They might challenge some of the facts alleged or advance facts of their own that put the charges of the nonprofit coalition into a different perspective.

Questions focusing on making thinking more precise include:

Could you give me more details?

Could you be more specific?

A statement can be both clear and accurate but not precise, as in "Jack is overweight." (We don't know how overweight Jack is - 1 pound or 500 pounds.) To be precise is to give the details needed for someone to understand exactly what is meant. Some situations don't call for detail. If you ask, "Is there any milk in the refrigerator?" and I answer "Yes," both the question and the answer are probably precise enough for the circumstance (though it might be relevant to specify how much milk is there). Or imagine that you are ill and go to the doctor. He wouldn't say, "Take 1.4876946 antibiotic pills twice per day." This level of specificity, or precision, would be beyond that which is useful in the situation.

In many situations, however, specifics are essential to good thinking. Let's say that your friend is having financial problems and asks you, "What should I do about my situation?" In this case, you want to probe her thinking for specifics. Without the full specifics, you could not help her. You might ask questions such as, "What precisely is the problem? What exactly are the variables that bear on the problem? What are some possible solutions to the problem-in detail?

Questions focusing on relevance include:

How is this idea connected to the question?

How does that bear on the issue?

How does this idea relate to this other idea?

How does your question relate to the issue we are dealing with?

A statement can be clear, accurate, and precise, but not relevant to the question at issue. For example, students often think the amount of effort they put into a course should contribute to raising their grade in the course. Often, however, effort does not measure the quality of student learning and therefore is irrelevant to the grade. Something is relevant when it is directly connected with and bears upon the issue at hand. Something is also relevant when it is pertinent or applicable to a problem we are trying to solve. Irrelevant thinking encourages us to consider what we should set aside. Thinking that is relevant stays on track. People are often irrelevant in their thinking because they lack discipline in thinking. They don't know how to analyze an issue for what truly bears on it. Therefore, they aren't able to effectively think their way through the problems and issues they face.

Questions focusing on depth of thought include:

How does your answer address the complexities in the question?

How are you taking into account the problems in the question?

How are you dealing with the most significant factors in the problem?

We think deeply when we get beneath the surface of an issue or problem, identify the complexities inherent in it, and then deal with those complexities in an intellectually responsible way. Even when we think deeply and deal well with the complexities in a question, we may find the question difficult to address. Still, our thinking will work better for us when we can recognize complicated questions and address each area of complexity in it.

A statement can be clear, accurate, precise, and relevant, but superficial - lacking in depth. Let's say you are asked what should be done about the problem of drug use in America and you answer by saying, "Just say no." This slogan, which was for several years used to discourage children and teens from using drugs, is clear, accurate, precise, and relevant. Nevertheless, it lacks depth because it treats an extremely complex issue superficially - i.e. it hardly addresses the pervasive problem of drug use among people in our culture. It does not address the history of the problem, the politics of the problem, the economics of the problem, the psychology of addiction, and so on.

Questions focusing on making thinking broader include:

Do we need to consider another point of view?

Is there another way to look at this question?

What would this look like from a conservative standpoint?

What would this look like from the point of view of...?

A line of reasoning may be clear, accurate, precise, relevant, and deep, but lack breadth. Examples are arguments from either the conservative or the liberal standpoint that get deeply into an issue but show insight into only one side of the question.

When we consider the issue at hand from every relevant viewpoint, we think in a broad way. When multiple points of view are pertinent to the issue, yet we fail to give due consideration to those perspectives, we think myopically, or narrow-mindedly. We do not try to understand alternative, or opposing, viewpoints.

Humans are frequently guilty of narrow-mindedness for many reasons: limited education, innate socio-centrism, natural selfishness, self-deception, and intellectual arrogance. Points of view that significantly disagree with our own often threaten us. It's much easier to ignore perspectives with which we disagree than to consider them, when we know at some level that to consider them would mean to be forced to reconsider our views.

Let's say, for example, that you like to watch / listen to TV in the bedroom as a way of falling to sleep. But let's say that your spouse has difficulty falling to sleep while the TV is on. The question at issue, then, is "Should you have the TV on in the bedroom while you and your spouse are falling asleep?" It is easy enough to rationalize your "need" to have the TV on every night while falling asleep, by saying such things to your spouse as "It is impossible for me to fall asleep without the TV on. And, after all, I really don't ask that much of you. Besides, you don't seem to have any real problem falling to sleep with the TV on." Yet both your viewpoint and your spouse's are relevant to the question at issue. When you recognize your spouse's viewpoint as relevant, and then intellectually empathize with it - when you enter her / his way of thinking so as to actually understand it - you will be thinking broadly about the issue. You will realize common consideration would require you to come to an agreement that fully takes into account both ways of looking at the situation. But if you don't force yourself to enter her/his viewpoint, you do not have to change your self-serving behavior. One of the primary mechanisms the mind uses to avoid giving up what it wants is unconsciously to refuse to enter viewpoints that differ from its own.

Questions that focus on making thinking more logical include:

Does all of this fit together logically?

Does this really make sense?

Does that follow from what you said?

How does that follow from the evidence?

Before, you implied this, and now you are saying that. I don't see how both can be true.

When we think, we bring together a variety of thoughts in some order. When the combined thoughts are mutually supporting and make sense in combination, the thinking is logical. When the combination is not mutually supporting, is contradictory in some sense, or does not make sense, the combination is not logical. Because humans often maintain conflicting beliefs without being aware that we are doing so, it is not unusual to find inconsistencies in human life and thought.

Let's say we know, by looking at standardized tests of students in schools and the actual work they are able to produce, that for the most part students are deficient in basic academic skills such as reading, writing, speaking, and the core disciplines such as math, science, and history. Despite this evidence, teachers often conclude that there is nothing they can do to change their instruction to improve student learning (and in fact that there is nothing fundamentally wrong with the way they teach). Given the evidence, this conclusion seems illogical. The conclusion doesn't seem to follow from the facts.

Let's take another example. Say that you know a person who has had a heart attack, and her doctors have told her she must be careful what she eats. Yet she concludes that what she eats really doesn't matter. Given the evidence, her conclusion is illogical. It doesn't make sense.

Questions that focus on making thinking more significant include:

What is the most significant information we need to address this issue?

How is that fact important in context?

Which of these questions is the most significant?

Which of these ideas or concepts is the most important?

When we reason through issues, we want to concentrate on the most important information (relevant to the issue) in our reasoning and take into account the most important ideas or concepts. Too often we fail in our thinking because we do not recognize that, though many ideas may be relevant to an issue, it does not follow that all are equally important. In a similar way, we often fail to ask the most important questions and are trapped by thinking only in terms of superficial questions, questions of little weight. In college, for example, few students focus on important questions such as, "What does it mean to be an educated person? What do I need to do to become educated?" Instead, students tend to ask questions such as, "What do I need to do to get an "A" in this course? How many pages does this paper have to be? What do I have to do to satisfy this professor?"

In our work, we too often focus on that which is pressing, at the expense of focusing on that which is significant. In our personal lives, we also often focus on the trivial mundane details, rather than the important bigger picture of our lives. Very few people, for example, have seriously thought about questions such as:

What is the most important thing I could do in my life?

What are the most important things I should try to accomplish this week, this month, this year?

How can I help my children become kind, caring, contributing members of society?

How can I best relate to my spouse so that she understands the deep love I feel for her?

How can I keep my mind focused on the things that matter most to me (rather than the unimportant trivial details)?

Questions that focus on ensuring that thinking is fair include:

Is my thinking justified given the evidence?

Am I taking into account the weight of the evidence that others might advance in the situation?

Are these assumptions justified?

Is my purpose fair given the implications of my behavior?

Is the manner in which I am addressing the problem fair - or is my vested interest keeping me from considering the problem from alternative viewpoints?

Am I using concepts justifiably, or am I using them unfairly in other to manipulate someone (and selfishly get what I want)?

When we think through problems, we want to make sure that our thinking is justified. To be justified is to think fairly in context. In other words, it is to think in accord with reason. If you are vigilant in using the other intellectual standards covered thus far in the chapter you will (by implication) satisfy the standard of fairness. We include fairness in its own section because of the powerful nature of self-deception in human thinking. For example, we often deceive ourselves into thinking that we are being fair and justified in our thinking when in fact we are refusing to consider significant relevant information that would cause us to change our view (and therefore not pursue our selfish interest). We often pursue unfair purposes in order to get what we want even if we have to hurt others to get it. We often use concepts in an unjustified way in order to manipulate people. And we often make unjustified assumptions, unsupported by facts, which then lead to faulty inferences.

Let's focus on an example where the problem is unjustified thinking owing to ignoring relevant facts. Let's say, for instance, that Kristi and Abbey share the same office. Kristi is cold natured and Abbey is warm-natured. During the winter, Abbey likes to have the window in the office open while Kristi likes to keep it closed. But Abbey insists that it's "extremely uncomfortable" with the window closed. The information she is using in her reasoning all centers around her own point of view - that she is hot, that she can't work effectively if she's hot, that if Kristi is cold she can wear a sweater. But the fact is that Abbey is not justified in her thinking. She refuses to enter Kristi's point of view, to consider information supporting Kristi's perspective, because to do so would mean that she would have to give something up. She would have to adopt a more reasonable, or fair, point of view.

When we reason to conclusions, we want to check to make sure that the assumptions we are using to come to those conclusions are justifiable given the facts of the situation. For example, all of our prejudices and stereotypes function as assumptions in thinking. And no prejudices and stereotypes are justifiable given their very nature. For example, we often make broad sweeping generalizations such as:

Liberals are soft on crime

Elderly people aren't interested in sex

Young men are only interested in sex

Jocks are cool

Blondes are dumb

Cheerleaders are airheads

Intellectuals are nerds

The problem with assumptions like these is that they cause us to make basic - and often serious - mistakes in thinking. Because they aren't justifiable, they cause us to prejudge situations and people and draw faulty inferences - or conclusions - about them. For example, if we believe that all intellectuals are nerds, whenever we meet an intellectual we will infer that he or she is a nerd (and act unfairly toward the person).

In sum, justifiability, or fairness, is an important standard in thinking because it forces us to see how we are distorting our thinking in order to achieve our self-serving ends (or to see how others are distorting their thinking to achieve selfish ends).

Bringing Together the Elements of Reasoning and the Intellectual Standards

We have considered the elements of reasoning and the importance of being able to take them apart, to analyze them so we can begin to recognize flaws in our thinking. We also have introduced the intellectual standards as tools for assessment. Now let us look at how the intellectual standards are used to assess the elements of reason ( Table 7.1 & Figure 7.1 ).

Figure 7.1. Critical thinkers routinely apply the intellectual standards to the elements of reasoning.

Purpose, goal, or end in view.

Whenever we reason, we do so to some end, to achieve an objective, to satisfy some desire or fulfill a need. One source of problems in human reasoning is traceable to defects at the level of goal, purpose, or end. If the goal is unrealistic, for example, or contradictory to other goals we have, if it is confused or muddled, the reasoning used to achieve it will suffer as a result.

As a developing critical thinker, then, you should get in the habit of explicitly stating the purposes you are trying to accomplish. You should strive to be clear about your purpose in every situation. If you fail to stick to your purpose, you are unlikely to achieve it. Let's say that your purpose in parenting is to help your children develop as life-long learners and contributing members of society. If you keep this purpose clearly in mind and consistently work to achieve it, you are more likely to be successful. But it is easy to lose sight of such an important purpose in the daily life of dealing with children. It is all too easy to get pulled into daily battles over whether a child's room is kept clean, whether they wear clothes considered "appropriate," whether they can get their nose pierced or their stomach tattooed. To achieve your purpose, you must revisit again and again what it is you are trying to accomplish. You must ask yourself on a daily basis questions like, "What have I done today to help my child develop as a rational, caring person?"

As an employee, you can begin to ask questions that improve your ability to focus on purpose in your work. For example: Am I clear as to my purpose - in this meeting, in this project, in dealing with this issue, in this discussion? Can I specify my purpose precisely? Is my purpose a significant one? Realistic? Achievable? Justifiable? Do I have contradictory purposes?

Question at Issue or Problem to Be Solved

Whenever you attempt to reason something through, there is at least one question to answer - one question that emerges from the problem to be solved or issue to resolve. An area of concern in assessing reasoning, therefore, revolves around the very question at issue.

An important part of being able to think well is assessing your ability to formulate a problem in a clear and relevant way. It requires determining whether the question you are addressing is an important one, whether it is answerable, whether you understand the requirements for settling the question, for solving the problem.

As an employee, you can begin to ask yourself questions that improve your ability to focus on the important questions in your work. You begin to ask: What is the most fundamental question at issue (in this meeting, in this project, in this discussion)? What is the question, precisely? Is the question simple or complex? If it is complex, what makes it complex? Am I sticking to the question (in this discussion, in this project I am working on)? Is there more than one important question to be considered here (in this meeting, etc.)?

Point of View, or Frame of Reference

Whenever we reason, we must reason within some point of view or frame of reference. Any "defect" in that point of view or frame of reference is a possible source of problems in the reasoning.

A point of view may be too narrow, may be based on false or misleading information, may contain contradictions, and may be narrow or unfair. Critical thinkers strive to adopt a point of view that is fair to others, even to opposing points of view. They want their point of view to be broad, flexible, and justifiable, to be clearly stated and consistently adhered to. Good thinkers, then, consider alternative points of view as they reason through an issue.

As an employee, you begin to ask yourself questions that improve your ability to focus on point of view in your work. These questions might be: From what point of view am I looking at this issue? Am I so locked into my point of view that I am unable to see the issue from other points of view? Must I consider multiple points of view to reason well through the issue at hand? What is the point of view of my colleague? How is she seeing things differently than I? Which of these perspectives seems more reasonable given the situation?

Information, Data, Experiences

Whenever we reason, there is some "stuff," some phenomena about which we are reasoning. Any "defect," then, in the experiences, data, evidence, or raw material upon which a person's reasoning is based is a possible source of problems.

Those who reason should be assessed on their ability to give evidence that is gathered and reported clearly, fairly, and accurately. Therefore, as a developing thinker, you should assess the information you use to come to conclusions, whether you are reasoning through issues at work or reasoning through a problem in your personal life. You should assess whether the information you are using in reasoning is relevant to the issue at hand and adequate for achieving your purpose. You should assess whether you are taking the information into account consistently or distorting it to fit your own (often self-serving) point of view.

At work, you can begin to ask yourself questions that improve your ability to focus on information in your work. These questions might be: What is the most important information I need to reason well through this issue? Are there alternate information sources I need to consider? How can I check to see if the information I am using is accurate? Am I sure that all of the information I am using is relevant to the issue at hand?

Concepts, Theories, Ideas

All reasoning uses some ideas or concepts and not others. These concepts include the theories, principles, axioms, and rules implicit in our reasoning. Any defect in the concepts or ideas of the reasoning is a possible source of problems in our reasoning.

As an aspiring critical thinker, you begin to focus more deeply on the concepts you use. You begin to assess the extent to which you are clear about those concepts, whether they are relevant to the issue at hand, and whether your principles are inappropriately slanted by your point of view. You begin to direct your attention to how you use concepts, what concepts are most important, and how concepts are intertwined in networks.

As a person interested in developing your mind, you begin to ask questions that improve your ability to focus on the importance of concepts in your life. These questions may include: What is the most fundamental concept I am focused on in this situation? How does this concept connect with other key concepts I need to consider? What are the most important theories I need to consider? Am I clear about the important concepts in this meeting? What questions do I need to ask to get clear about the concepts we are discussing?

Assumptions

All reasoning must begin somewhere. It must take some things for granted. Any defect in the assumptions or presuppositions with which reasoning begins is a possible source of problems in the reasoning.

Assessing skills of reasoning involves assessing our ability to recognize and articulate assumptions, again according to relevant standards. Our assumptions may be clear or unclear, justifiable or unjustifiable, consistent or contradictory.

As a person interested in developing your mind, you begin to ask questions that improve your ability to analyze the assumptions you and others are using. These questions could include: What am I taking for granted? Am I justified in taking this for granted? What are others taking for granted? What is being assumed in this meeting? What is being assumed in this relationship? What is being assumed in this discussion? Are these assumptions justifiable, or should I question them?

Implications and Consequences

Whenever we reason, implications follow from our reasoning. When we make decisions, consequences result from those decisions. As critical thinkers, we want to understand implications whenever and wherever they occur. We want to be able to trace logical consequences. We want to see what our actions are leading to. We want to anticipate possible problems before they arise.

No matter where we stop tracing implications, there always will be further implications. No matter what consequences we do see, there always will be other and further consequences. Any defect in our ability to follow the implications or consequences of our reasoning is a potential source of problems in our thinking. Our ability to reason well, then, is measured in part by our ability to understand and enunciate the implications and consequences of reasoning.

In your work and personal life, you begin to ask yourself questions that improve your ability to focus on the important implications in your thinking and the thinking of others. These questions could include, for example: What are the most important implications of this decision? What are the implications of my doing this versus my doing that? Have we thought through the implications decision in this meeting? Have I thought through the implications of my parenting behavior? Have I thought through the implications of the way I treat my spouse?

All reasoning proceeds by steps in which we reason as follows: "Because this is so, that also is so (or is probably so)" or, "Because this, therefore that." The mind perceives a situation or a set of facts and comes to a conclusion based on those facts. When this step of the mind occurs, an inference is made. Any defect in our ability to make logical inferences is a possible problem in our reasoning. For example, if you see a person sitting on the street corner wearing tattered clothing, a worn bed roll beside him and a bottle wrapped in a brown paper bag in his hand, you might infer that he is a bum. This inference is based on the facts you perceive in the situation and of what you assume about them. The inference, however, may or may not be logical in this situation.

Critical thinkers want to become adept at making sound inferences. First, you want to learn to identify when you or someone else has made an inference. What are the key inferences made in this discussion? Upon what are the inferences based? Are they justified? What is the key inference (or conclusion) I made in this meeting? Was it justified? What is the key inference in this way of proceeding, in solving this problem in this way? Is this inference logical? Is this conclusion significant? Is this interpretation justified? These are the kinds of questions you begin to ask.

As a person interested in developing your mind, you should ask questions that improve your ability to spot important inferences wherever they occur. Given the facts of this case, is there more than one logical inference (conclusion, interpretation) one could come to? What are some other logical conclusions that should be considered? From this point on, develop an inference detector, the skill of recognizing the inferences you are making in order to analyze them.

Using Intellectual Standards to Assess Your Thinking: Brief Guidelines

As we have emphasized, all reasoning involves eight elements, each of which has a range of possible mistakes. Here we summarize some of the main "checkpoints" you should use in reasoning (See also Tables 7.2 � 7.9 ).

Take time to state your purpose clearly.

Choose significant and realistic purposes.

Distinguish your purpose from related purposes.

Make sure your purpose is fair in context (that it doesn't involve violating the rights of others).

Check periodically to be sure you are still focused on your purpose and haven't wandered from your target.

Take time to clearly and precisely state the question at issue.

Express the question in several ways to clarify its meaning and scope.

Break the question into sub-questions (when you can).

Identify the type of question you are dealing with (historical, economic, biological, etc.) and whether the question has one right answer, is a matter of mere opinion, or requires reasoning from more than one point of view.

Think through the complexities of the question (think deeply through the question).

Clearly identify your assumptions and determine whether they are justifiable.

Consider how your assumptions are shaping your point of view.

Clearly identify your point of view.

Seek other relevant points of view and identify their strengths as well as weaknesses.

Strive to be fair-minded in evaluating all points of view.

Restrict your claims to those supported by the data you have.

Search for information that opposes your position as well as information that supports it.

Make sure that all information used is clear, accurate, and relevant to the question at issue.

Make sure you have gathered sufficient information.

Make sure, especially, that you have considered all significant information relevant to the issue.

Clearly identify key concepts.

Consider alternative concepts or alternative definitions for concepts.

Make sure you are using concepts with care and precision.

Use concepts justifiably (not distorting their established meanings).

Infer only what the evidence implies.

Check inferences for their consistency with each other.

Identify assumptions that lead you to your inferences.

Make sure your inferences logically follow from the information.

Trace the logical implications and consequences that follow from your reasoning.

Search for negative as well as positive implications.

Consider all possible significant consequences.

[*] Monological problems are ones for which there are definite correct and incorrect answers and definite procedures for getting those answers. In multilogical problems, there are competing schools of thought to be considered.

Westside Toastmasters on Meetup

IMAGES

VIDEO