Speech Thesis Statement

Speech thesis statement generator.

In the realm of effective communication, crafting a well-structured and compelling speech thesis statement is paramount. A speech thesis serves as the bedrock upon which impactful oratory is built, encapsulating the core message, purpose, and direction of the discourse. This exploration delves into diverse speech thesis statement examples, offering insights into the art of formulating them. Moreover, it provides valuable tips to guide you in crafting speeches that resonate powerfully with your audience and leave a lasting impact.

What is a Speech Thesis Statement? – Definition

A speech thesis statement is a succinct and focused declaration that encapsulates the central argument, purpose, or message of a speech. It outlines the primary idea the speaker intends to convey to the audience, serving as a guide for the content and structure of the speech.

What is an Example of Speech Thesis Statement?

“In this speech, I will argue that implementing stricter gun control measures is essential for reducing gun-related violence and ensuring public safety. By examining statistical data, addressing common misconceptions, and advocating for comprehensive background checks, we can take meaningful steps toward a safer society.”

In this example, the speech’s main argument, key points (statistics, misconceptions, background checks), and the intended impact (safer society) are all succinctly conveyed in the thesis statement.

100 Speech Thesis Statement Examples

- “Today, I will convince you that renewable energy sources are the key to a sustainable and cleaner future.”

- “In this speech, I will explore the importance of mental health awareness and advocate for breaking the stigma surrounding it.”

- “My aim is to persuade you that adopting a plant-based diet contributes not only to personal health but also to environmental preservation.”

- “In this speech, I will discuss the benefits of exercise on cognitive function and share practical tips for integrating physical activity into our daily routines.”

- “Today, I’ll argue that access to quality education is a fundamental right for all, and I’ll present strategies to bridge the educational gap.”

- “My speech centers around the significance of arts education in fostering creativity, critical thinking, and overall cognitive development in students.”

- “Through this speech, I’ll shed light on the impact of plastic pollution on marine ecosystems and inspire actionable steps toward plastic reduction.”

- “My aim is to persuade you that stricter regulations on social media platforms are imperative to combat misinformation and protect user privacy.”

- “Today, I’ll discuss the importance of empathy in building strong interpersonal relationships and provide techniques to cultivate empathy in daily interactions.”

- “In this speech, I’ll present the case for implementing universal healthcare, emphasizing its benefits for both individual health and societal well-being.”

- “My speech highlights the urgency of addressing climate change and calls for international collaboration in reducing carbon emissions.”

- “I will argue that the arts play a crucial role in fostering cultural understanding, breaking down stereotypes, and promoting global harmony.”

- “Through this speech, I’ll advocate for the preservation of endangered species and offer strategies to contribute to wildlife conservation efforts.”

- “Today, I’ll discuss the power of effective time management in enhancing productivity and share practical techniques to prioritize tasks.”

- “My aim is to convince you that raising the minimum wage is vital to reducing income inequality and improving the overall quality of life.”

- “In this speech, I’ll explore the societal implications of automation and artificial intelligence and propose strategies for a smooth transition into the future.”

- “Through this speech, I’ll emphasize the significance of volunteering in community development and suggest ways to get involved in meaningful initiatives.”

- “I will argue that stricter regulations on fast food advertising are necessary to address the growing obesity epidemic among children and adolescents.”

- “Today, I’ll discuss the importance of financial literacy in personal empowerment and provide practical advice for making informed financial decisions.”

- “My speech focuses on the value of cultural diversity in enriching society, fostering understanding, and promoting a more inclusive world.”

- “In this speech, I’ll present the case for investing in renewable energy technologies to mitigate the adverse effects of climate change on future generations.”

- “I will argue that embracing failure as a stepping stone to success is crucial for personal growth and achieving one’s fullest potential.”

- “Through this speech, I’ll examine the impact of social media on mental health and offer strategies to maintain a healthy online presence.”

- “Today, I’ll emphasize the importance of effective communication skills in professional success and share tips for honing these skills.”

- “My aim is to persuade you that stricter gun control measures are essential to reduce gun-related violence and ensure public safety.”

- “In this speech, I’ll discuss the significance of cultural preservation and the role of heritage sites in maintaining the identity and history of communities.”

- “I will argue that promoting diversity and inclusion in the workplace leads to enhanced creativity, collaboration, and overall organizational success.”

- “Through this speech, I’ll explore the impact of social media on political engagement and discuss ways to critically evaluate online information sources.”

- “Today, I’ll present the case for investing in public transportation infrastructure to alleviate traffic congestion, reduce pollution, and enhance urban mobility.”

- “My aim is to persuade you that implementing mindfulness practices in schools can improve students’ focus, emotional well-being, and overall academic performance.”

- “In this speech, I’ll discuss the importance of supporting local businesses for economic growth, community vibrancy, and sustainable development.”

- “I will argue that fostering emotional intelligence in children equips them with crucial skills for interpersonal relationships, empathy, and conflict resolution.”

- “Through this speech, I’ll emphasize the need for comprehensive sex education that addresses consent, healthy relationships, and informed decision-making.”

- “Today, I’ll explore the benefits of embracing a minimalist lifestyle for mental clarity, reduced stress, and a more mindful and sustainable way of living.”

- “My aim is to persuade you that sustainable farming practices are essential for preserving ecosystems, ensuring food security, and mitigating climate change.”

- “In this speech, I’ll discuss the importance of civic engagement in democracy and provide strategies for individuals to get involved in their communities.”

- “I will argue that investing in early childhood education not only benefits individual children but also contributes to a stronger and more prosperous society.”

- “Through this speech, I’ll examine the impact of social media on body image dissatisfaction and offer strategies to promote body positivity and self-acceptance.”

- “Today, I’ll present the case for stricter regulations on e-cigarette marketing and sales to curb youth vaping and protect public health.”

- “My aim is to persuade you that exploring nature and spending time outdoors is essential for mental and physical well-being in our technology-driven world.”

- “In this speech, I’ll discuss the implications of automation on employment and suggest strategies for reskilling and preparing for the future of work.”

- “I will argue that embracing failure as a valuable learning experience fosters resilience, innovation, and personal growth, leading to ultimate success.”

- “Through this speech, I’ll emphasize the significance of media literacy in discerning credible information from fake news and ensuring informed decision-making.”

- “Today, I’ll explore the benefits of implementing universal healthcare, focusing on improved access to medical services and enhanced public health outcomes.”

- “My aim is to persuade you that embracing sustainable travel practices can minimize the environmental impact of tourism and promote cultural exchange.”

- “In this speech, I’ll present the case for criminal justice reform, highlighting the importance of alternatives to incarceration for nonviolent offenders.”

- “I will argue that instilling a growth mindset in students enhances their motivation, learning abilities, and willingness to face challenges.”

- “Through this speech, I’ll discuss the implications of artificial intelligence on the job market and propose strategies for adapting to automation-driven changes.”

- “Today, I’ll emphasize the importance of digital privacy awareness and provide practical tips to safeguard personal information online.”

- “My aim is to persuade you that investing in renewable energy sources is crucial not only for environmental sustainability but also for economic growth.”

- “In this speech, I’ll discuss the significance of cultural preservation and the role of heritage sites in maintaining a sense of identity and history.”

- “I will argue that promoting diversity and inclusion in the workplace leads to improved creativity, collaboration, and overall organizational performance.”

- “Through this speech, I’ll explore the impact of social media on political engagement and offer strategies to critically assess online information.”

- “Today, I’ll present the case for investing in public transportation to alleviate traffic congestion, reduce emissions, and enhance urban mobility.”

- “My aim is to persuade you that implementing mindfulness practices in schools can enhance students’ focus, emotional well-being, and academic achievement.”

- “In this speech, I’ll discuss the importance of supporting local businesses for economic growth, community vitality, and sustainable development.”

- “I will argue that fostering emotional intelligence in children equips them with essential skills for healthy relationships, empathy, and conflict resolution.”

- “Through this speech, I’ll emphasize the need for comprehensive sex education that includes consent, healthy relationships, and informed decision-making.”

- “My aim is to persuade you that sustainable farming practices are vital for preserving ecosystems, ensuring food security, and combating climate change.”

- “In this speech, I’ll discuss the importance of civic engagement in democracy and provide strategies for individuals to actively participate in their communities.”

- “I will argue that investing in early childhood education benefits not only individual children but also contributes to a stronger and more prosperous society.”

- “Through this speech, I’ll examine the impact of social media on body image dissatisfaction and suggest strategies to promote body positivity and self-acceptance.”

- “Today, I’ll present the case for stricter regulations on e-cigarette marketing and sales to combat youth vaping and protect public health.”

- “My aim is to persuade you that connecting with nature and spending time outdoors is essential for mental and physical well-being in our technology-driven world.”

- “In this speech, I’ll discuss the implications of automation on employment and suggest strategies for reskilling and adapting to the changing job landscape.”

- “I will argue that embracing failure as a valuable learning experience fosters resilience, innovation, and personal growth, ultimately leading to success.”

- “Through this speech, I’ll emphasize the significance of media literacy in discerning credible information from fake news and making informed decisions.”

- “Today, I’ll explore the benefits of implementing universal healthcare, focusing on improved access to medical services and better public health outcomes.”

- “My aim is to persuade you that adopting sustainable travel practices can minimize the environmental impact of tourism and promote cultural exchange.”

- “I will argue that instilling a growth mindset in students enhances their motivation, learning abilities, and readiness to tackle challenges.”

- “Through this speech, I’ll discuss the implications of artificial intelligence on the job market and propose strategies for adapting to the changing landscape.”

- “Today, I’ll emphasize the importance of digital privacy awareness and provide practical tips to safeguard personal information in the online world.”

- “My aim is to persuade you that investing in renewable energy sources is essential for both environmental sustainability and economic growth.”

- “In this speech, I’ll discuss the transformative power of art therapy in promoting mental well-being and share real-life success stories.”

- “I will argue that promoting gender equality not only empowers women but also contributes to economic growth and social progress.”

- “Through this speech, I’ll explore the impact of technology on interpersonal relationships and offer strategies to maintain meaningful connections.”

- “Today, I’ll present the case for sustainable fashion choices, emphasizing their positive effects on the environment and ethical manufacturing practices.”

- “My aim is to persuade you that investing in early childhood education is an investment in the future, leading to a more educated and equitable society.”

- “In this speech, I’ll discuss the significance of community service in building strong communities and share personal stories of volunteering experiences.”

- “I will argue that fostering emotional intelligence in children lays the foundation for a harmonious and empathetic society.”

- “Through this speech, I’ll emphasize the importance of teaching critical thinking skills in education and how they empower individuals to navigate a complex world.”

- “Today, I’ll explore the benefits of embracing a growth mindset in personal and professional development, leading to continuous learning and improvement.”

- “My aim is to persuade you that conscious consumerism can drive positive change in industries by supporting ethical practices and environmentally friendly products.”

- “In this speech, I’ll present the case for renewable energy as a solution to energy security, reduced carbon emissions, and a cleaner environment.”

- “I will argue that investing in mental health support systems is essential for the well-being of individuals and society as a whole.”

- “Through this speech, I’ll discuss the role of music therapy in enhancing mental health and promoting emotional expression and healing.”

- “Today, I’ll emphasize the importance of embracing cultural diversity to foster global understanding, harmony, and peaceful coexistence.”

- “My aim is to persuade you that incorporating mindfulness practices into daily routines can lead to reduced stress and increased overall well-being.”

- “In this speech, I’ll discuss the implications of genetic engineering and gene editing technologies on ethical considerations and future generations.”

- “I will argue that investing in renewable energy infrastructure not only mitigates climate change but also generates job opportunities and economic growth.”

- “Through this speech, I’ll explore the impact of social media on political polarization and offer strategies for promoting constructive online discourse.”

- “Today, I’ll present the case for embracing experiential learning in education, focusing on hands-on experiences that enhance comprehension and retention.”

- “My aim is to persuade you that practicing gratitude can lead to improved mental health, increased happiness, and a more positive outlook on life.”

- “In this speech, I’ll discuss the importance of teaching financial literacy in schools to equip students with essential money management skills.”

- “I will argue that promoting sustainable agriculture practices is essential to ensure food security, protect ecosystems, and combat climate change.”

- “Through this speech, I’ll emphasize the need for greater awareness of mental health issues in society and the importance of reducing stigma.”

- “Today, I’ll explore the benefits of incorporating arts and creativity into STEM education to foster innovation, critical thinking, and problem-solving.”

- “My aim is to persuade you that practicing mindfulness and meditation can lead to improved focus, reduced anxiety, and enhanced overall well-being.”

Speech Thesis Statement for Introduction

Introductions set the tone for impactful speeches. These thesis statements encapsulate the essence of opening remarks, laying the foundation for engaging discourse.

- “Welcome to an exploration of the power of storytelling and its ability to bridge cultures and foster understanding across diverse backgrounds.”

- “In this introductory speech, we delve into the realm of artificial intelligence, examining its potential to reshape industries and redefine human capabilities.”

- “Join us as we navigate the fascinating world of space exploration and the role of technological advancements in uncovering the mysteries of the universe.”

- “Through this speech, we embark on a journey through history, highlighting pivotal moments that have shaped civilizations and continue to inspire change.”

- “Today, we embark on a discussion about the significance of empathy in our interactions, exploring how it can enrich our connections and drive positive change.”

- “In this opening address, we dive into the realm of sustainable living, exploring practical steps to reduce our environmental footprint and promote eco-consciousness.”

- “Join us as we explore the evolution of communication, from ancient symbols to modern technology, and its impact on how we connect and convey ideas.”

- “Welcome to an exploration of the intricate relationship between art and emotion, uncovering how artistic expression transcends language barriers and unites humanity.”

- “In this opening statement, we examine the changing landscape of work and career, discussing strategies to navigate career transitions and embrace lifelong learning.”

- “Today, we delve into the concept of resilience and its role in facing adversity, offering insights into how resilience can empower us to overcome challenges.”

Speech Thesis Statement for Graduation

Graduation speeches mark significant milestones. These thesis statements encapsulate the achievements, aspirations, and challenges faced by graduates as they move forward.

- “As we stand on the threshold of a new chapter, let’s reflect on our journey, celebrate our achievements, and embrace the uncertainties that lie ahead.”

- “In this graduation address, we celebrate not only our academic accomplishments but also the personal growth, resilience, and friendships that have enriched our years here.”

- “As we step into the world beyond academia, let’s remember that learning is a lifelong journey, and the skills we’ve honed will propel us toward success.”

- “Today, we bid farewell to the familiar and embrace the unknown, armed with the knowledge that every challenge we face is an opportunity for growth.”

- “In this commencement speech, we acknowledge the collective accomplishments of our class and embrace the responsibility to contribute positively to the world.”

- “As we graduate, let’s carry with us the values instilled by our education, applying them not only in our careers but also in shaping a more just and compassionate society.”

- “Join me in celebrating the diversity of talents and perspectives that define our graduating class, and let’s channel our unique strengths to make a meaningful impact.”

- “Today, we honor the culmination of our academic pursuits and embrace the journey of continuous learning that will shape our personal and professional paths.”

- “In this graduation address, we acknowledge the support of our families, educators, and peers, recognizing that our successes are a testament to shared effort.”

- “As we don our caps and gowns, let’s remember that our education equips us not only with knowledge but also with the power to effect positive change in the world.”

Speech Thesis Statement For Acceptance

Acceptance speeches express gratitude and acknowledge achievements. These thesis statements capture the essence of acknowledgment, appreciation, and commitment.

- “I am humbled and honored by this recognition, and I pledge to use this platform to amplify the voices of the marginalized and work toward equity.”

- “As I accept this award, I express my gratitude to those who believed in my potential, and I commit to using my skills to contribute meaningfully to our community.”

- “Receiving this honor is a testament to the collaborative efforts that make achievements possible. I am dedicated to sharing this success with those who supported me.”

- “Accepting this award, I am reminded of the responsibility that accompanies it. I vow to continue striving for excellence and inspiring those around me.”

- “As I receive this recognition, I extend my deepest appreciation to my mentors, colleagues, and family, and I promise to pay it forward by mentoring the next generation.”

- “Accepting this accolade, I recognize that success is a team effort. I commit to fostering a culture of collaboration and innovation in all my endeavors.”

- “Receiving this honor, I am reminded of the privilege I have to effect change. I dedicate myself to leveraging this platform for the betterment of society.”

- “Accepting this award, I am grateful for the opportunities that have shaped my journey. I am committed to using my influence to uplift others and drive positive change.”

- “As I stand here, I am deeply moved by this recognition. I pledge to use this honor as a catalyst for making a meaningful impact on the lives of those I encounter.”

- “Accepting this distinction, I embrace the responsibility it brings. I promise to uphold the values that guided me to this moment and channel my efforts toward progress.”

Speech Thesis Statement in Extemporaneous

Extemporaneous speeches require quick thinking and concise communication. These thesis statements capture the essence of on-the-spot analysis and delivery.

- “On the topic of technological disruption, we explore its effects on job markets, emphasizing the importance of upskilling for the workforce’s evolving demands.”

- “In this impromptu speech, we dissect the complexities of global climate agreements, assessing their impact on environmental sustainability and international cooperation.”

- “Addressing the issue of cyberbullying, we examine its psychological consequences, potential legal remedies, and strategies to create safer online spaces.”

- “Discussing the merits of universal basic income, we weigh its potential to alleviate poverty, stimulate economic growth, and reshape the social safety net.”

- “As we delve into the debate on genetically modified organisms, we consider the benefits of increased crop yields, while also evaluating environmental and health concerns.”

- “On the topic of urbanization, we analyze its benefits in fostering economic growth and cultural exchange, while addressing challenges of infrastructure and inequality.”

- “Delving into the controversy surrounding artificial intelligence, we explore its transformative potential in various sectors, touching on ethical considerations and fears of job displacement.”

- “In this impromptu speech, we examine the impact of social media on political discourse, highlighting the role of echo chambers and the need for critical thinking.”

- “Addressing the issue of mental health stigma, we discuss the societal barriers that prevent seeking help, while advocating for open conversations and destigmatization.”

- “Discussing the concept of ethical consumerism, we weigh the impact of consumer choices on industries, environment, and labor rights, emphasizing the power of informed purchasing.”

Speech Thesis Statement in Argumentative Essay

Argumentative speeches present clear stances on contentious topics. These thesis statements assert positions while indicating the direction of the ensuing debate.

- “In this argumentative speech, we assert that mandatory voting fosters civic participation and strengthens democracy by ensuring diverse voices are heard.”

- “Advocating for stricter gun control, we contend that regulations on firearm access are vital for public safety, reducing gun violence, and preventing tragedies.”

- “Arguing for the benefits of school uniforms, we posit that uniforms promote a focused learning environment, reduce socioeconomic disparities, and enhance school spirit.”

- “In this persuasive speech, we assert that capital punishment should be abolished due to its potential for wrongful executions, lack of deterrence, and ethical concerns.”

- “Taking a stand against standardized testing, we argue that these assessments stifle creativity, promote rote learning, and fail to measure true intellectual potential.”

- “Defending the benefits of renewable energy, we assert that transitioning to sustainable sources will mitigate climate change, create jobs, and reduce dependence on fossil fuels.”

- “Addressing the merits of open borders, we contend that welcoming immigrants bolsters cultural diversity, contributes to economic growth, and upholds humanitarian values.”

- “In this persuasive speech, we argue against the use of animal testing, asserting that modern alternatives exist to ensure scientific progress without unnecessary suffering.”

- “Advocating for comprehensive sex education, we assert that teaching about contraception, consent, and healthy relationships equips students to make informed choices.”

- “Arguing for universal healthcare, we posit that accessible medical services are a basic human right, contributing to improved public health, reduced disparities, and economic stability.”

These examples offer a range of thesis statements for various types of speeches, catering to different contexts and styles of presentation. Tailor them to fit your specific needs and adjust the content as necessary to create impactful speeches.

Is There a Thesis Statement in a Speech?

Yes, a thesis statement is an essential component of a speech. Just like in written essays, a thesis statement in a speech serves as the central point or main idea that the speaker wants to convey to the audience. It provides focus, direction, and a preview of the content that will follow in the speech. A well-crafted thesis statement helps the audience understand the purpose of the speech and what they can expect to learn or gain from listening.

What is the Thesis Structure of a Speech?

The structure of a thesis statement in a speech is similar to that of a thesis statement in an essay, but it’s adapted for the spoken format. A speech thesis generally consists of:

- Topic: Clearly state the topic or subject of your speech. This provides the context for your thesis and gives the audience an idea of the subject matter.

- Main Idea or Argument: Present the main point you want to make or the central argument you’ll be discussing in your speech. This should be a concise and focused statement that encapsulates the essence of your message.

- Supporting Points: Optionally, you can include a brief overview of the main supporting points or arguments that you’ll elaborate on in the body of your speech. This gives the audience an outline of what to expect.

How Do You Write a Speech Thesis Statement? – Step by Step Guide

- Choose Your Topic: Select a topic that is relevant to your audience and aligns with the purpose of your speech.

- Identify Your Main Message: Determine the central message or argument you want to convey. What is the key takeaway you want your audience to remember?

- Craft a Concise Statement: Write a clear and concise sentence that captures the essence of your main message. Make sure it’s specific and avoids vague language.

- Consider Your Audience: Tailor your thesis statement to your audience’s level of understanding and interests. Use language that resonates with them.

- Review and Refine: Read your thesis statement aloud to ensure it sounds natural and engaging. Refine it as needed to make it compelling.

Tips for Writing a Speech Thesis Statement

- Be Specific: A strong thesis statement is specific and focused. Avoid vague or general statements.

- Avoid Jargon: Use language that your audience can easily understand, avoiding complex jargon or technical terms unless you explain them.

- One Main Idea: Stick to one main idea or argument. Multiple ideas can confuse your audience.

- Preview Supporting Points: If applicable, briefly preview the main supporting points you’ll cover in your speech.

- Reflect the Purpose: Your thesis should reflect the purpose of your speech—whether it’s to inform, persuade, entertain, or inspire.

- Keep It Concise: A thesis statement is not a paragraph. Keep it to a single sentence that encapsulates your message.

- Practice Pronunciation: If your thesis statement includes challenging words or terms, practice pronouncing them clearly.

- Test for Clarity: Ask someone to listen to your thesis statement and summarize what they understood from it. This can help you gauge its clarity.

- Revise as Necessary: Don’t be afraid to revise your thesis statement as you refine your speech. It’s important that it accurately represents your content.

- Capture Interest: Craft your thesis statement in a way that captures the audience’s interest and curiosity, encouraging them to listen attentively.

Remember, the thesis statement sets the tone for your entire speech. It should be well-crafted, engaging, and reflective of the main message you want to communicate to your audience.

Text prompt

- Instructive

- Professional

Create a Speech Thesis Statement on the importance of voting

Write a Speech Thesis Statement for a talk on renewable energy benefits

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

9.3 Putting It Together: Steps to Complete Your Introduction

Learning objectives.

- Clearly identify why an audience should listen to a speaker.

- Discuss how you can build your credibility during a speech.

- Understand how to write a clear thesis statement.

- Design an effective preview of your speech’s content for your audience.

Erin Brown-John – puzzle – CC BY-NC 2.0.

Once you have captured your audience’s attention, it’s important to make the rest of your introduction interesting, and use it to lay out the rest of the speech. In this section, we are going to explore the five remaining parts of an effective introduction: linking to your topic, reasons to listen, stating credibility, thesis statement, and preview.

Link to Topic

After the attention-getter, the second major part of an introduction is called the link to topic. The link to topic is the shortest part of an introduction and occurs when a speaker demonstrates how an attention-getting device relates to the topic of a speech. Often the attention-getter and the link to topic are very clear. For example, if you look at the attention-getting device example under historical reference above, you’ll see that the first sentence brings up the history of the Vietnam War and then shows us how that war can help us understand the Iraq War. In this case, the attention-getter clearly flows directly to the topic. However, some attention-getters need further explanation to get to the topic of the speech. For example, both of the anecdote examples (the girl falling into the manhole while texting and the boy and the filberts) need further explanation to connect clearly to the speech topic (i.e., problems of multitasking in today’s society).

Let’s look at the first anecdote example to demonstrate how we could go from the attention-getter to the topic.

In July 2009, a high school girl named Alexa Longueira was walking along a main boulevard near her home on Staten Island, New York, typing in a message on her cell phone. Not paying attention to the world around her, she took a step and fell right into an open manhole. This anecdote illustrates the problem that many people are facing in today’s world. We are so wired into our technology that we forget to see what’s going on around us—like a big hole in front of us.

In this example, the third sentence here explains that the attention-getter was an anecdote that illustrates a real issue. The fourth sentence then introduces the actual topic of the speech.

Let’s now examine how we can make the transition from the parable or fable attention-getter to the topic:

The ancient Greek writer Aesop told a fable about a boy who put his hand into a pitcher of filberts. The boy grabbed as many of the delicious nuts as he possibly could. But when he tried to pull them out, his hand wouldn’t fit through the neck of the pitcher because he was grasping so many filberts. Instead of dropping some of them so that his hand would fit, he burst into tears and cried about his predicament. The moral of the story? “Don’t try to do too much at once.” In today’s world, many of us are us are just like the boy putting his hand into the pitcher. We are constantly trying to grab so much or do so much that it prevents us from accomplishing our goals. I would like to show you three simple techniques to manage your time so that you don’t try to pull too many filberts from your pitcher.

In this example, we added three new sentences to the attention-getter to connect it to the speech topic.

Reasons to Listen

Once you have linked an attention-getter to the topic of your speech, you need to explain to your audience why your topic is important. We call this the “why should I care?” part of your speech because it tells your audience why the topic is directly important to them. Sometimes you can include the significance of your topic in the same sentence as your link to the topic, but other times you may need to spell out in one or two sentences why your specific topic is important.

People in today’s world are very busy, and they do not like their time wasted. Nothing is worse than having to sit through a speech that has nothing to do with you. Imagine sitting through a speech about a new software package you don’t own and you will never hear of again. How would you react to the speaker? Most of us would be pretty annoyed at having had our time wasted in this way. Obviously, this particular speaker didn’t do a great job of analyzing her or his audience if the audience isn’t going to use the software package—but even when speaking on a topic that is highly relevant to the audience, speakers often totally forget to explain how and why it is important.

Appearing Credible

The next part of a speech is not so much a specific “part” as an important characteristic that needs to be pervasive throughout your introduction and your entire speech. As a speaker, you want to be seen as credible (competent, trustworthy, and caring/having goodwill). As mentioned earlier in this chapter, credibility is ultimately a perception that is made by your audience. While your audience determines whether they perceive you as competent, trustworthy, and caring/having goodwill, there are some strategies you can employ to make yourself appear more credible.

First, to make yourself appear competent, you can either clearly explain to your audience why you are competent about a given subject or demonstrate your competence by showing that you have thoroughly researched a topic by including relevant references within your introduction. The first method of demonstrating competence—saying it directly—is only effective if you are actually a competent person on a given subject. If you are an undergraduate student and you are delivering a speech about the importance of string theory in physics, unless you are a prodigy of some kind, you are probably not a recognized expert on the subject. Conversely, if your number one hobby in life is collecting memorabilia about the Three Stooges, then you may be an expert about the Three Stooges. However, you would need to explain to your audience your passion for collecting Three Stooges memorabilia and how this has made you an expert on the topic.

If, on the other hand, you are not actually a recognized expert on a topic, you need to demonstrate that you have done your homework to become more knowledgeable than your audience about your topic. The easiest way to demonstrate your competence is through the use of appropriate references from leading thinkers and researchers on your topic. When you demonstrate to your audience that you have done your homework, they are more likely to view you as competent.

The second characteristic of credibility, trustworthiness, is a little more complicated than competence, for it ultimately relies on audience perceptions. One way to increase the likelihood that a speaker will be perceived as trustworthy is to use reputable sources. If you’re quoting Dr. John Smith, you need to explain who Dr. John Smith is so your audience will see the quotation as being more trustworthy. As speakers we can easily manipulate our sources into appearing more credible than they actually are, which would be unethical. When you are honest about your sources with your audience, they will trust you and your information more so than when you are ambiguous. The worst thing you can do is to out-and-out lie about information during your speech. Not only is lying highly unethical, but if you are caught lying, your audience will deem you untrustworthy and perceive everything you are saying as untrustworthy. Many speakers have attempted to lie to an audience because it will serve their own purposes or even because they believe their message is in their audience’s best interest, but lying is one of the fastest ways to turn off an audience and get them to distrust both the speaker and the message.

The third characteristic of credibility to establish during the introduction is the sense of caring/goodwill. While some unethical speakers can attempt to manipulate an audience’s perception that the speaker cares, ethical speakers truly do care about their audiences and have their audience’s best interests in mind while speaking. Often speakers must speak in front of audiences that may be hostile toward the speaker’s message. In these cases, it is very important for the speaker to explain that he or she really does believe her or his message is in the audience’s best interest. One way to show that you have your audience’s best interests in mind is to acknowledge disagreement from the start:

Today I’m going to talk about why I believe we should enforce stricter immigration laws in the United States. I realize that many of you will disagree with me on this topic. I used to believe that open immigration was a necessity for the United States to survive and thrive, but after researching this topic, I’ve changed my mind. While I may not change all of your minds today, I do ask that you listen with an open mind, set your personal feelings on this topic aside, and judge my arguments on their merits.

While clearly not all audience members will be open or receptive to opening their minds and listening to your arguments, by establishing that there is known disagreement, you are telling the audience that you understand their possible views and are not trying to attack their intellect or their opinions.

Thesis Statement

A thesis statement is a short, declarative sentence that states the purpose, intent, or main idea of a speech. A strong, clear thesis statement is very valuable within an introduction because it lays out the basic goal of the entire speech. We strongly believe that it is worthwhile to invest some time in framing and writing a good thesis statement. You may even want to write your thesis statement before you even begin conducting research for your speech. While you may end up rewriting your thesis statement later, having a clear idea of your purpose, intent, or main idea before you start searching for research will help you focus on the most appropriate material. To help us understand thesis statements, we will first explore their basic functions and then discuss how to write a thesis statement.

Basic Functions of a Thesis Statement

A thesis statement helps your audience by letting them know “in a nutshell” what you are going to talk about. With a good thesis statement you will fulfill four basic functions: you express your specific purpose, provide a way to organize your main points, make your research more effective, and enhance your delivery.

Express Your Specific Purpose

To orient your audience, you need to be as clear as possible about your meaning. A strong thesis will prepare your audience effectively for the points that will follow. Here are two examples:

- “Today, I want to discuss academic cheating.” (weak example)

- “Today, I will clarify exactly what plagiarism is and give examples of its different types so that you can see how it leads to a loss of creative learning interaction.” (strong example)

The weak statement will probably give the impression that you have no clear position about your topic because you haven’t said what that position is. Additionally, the term “academic cheating” can refer to many behaviors—acquiring test questions ahead of time, copying answers, changing grades, or allowing others to do your coursework—so the specific topic of the speech is still not clear to the audience.

The strong statement not only specifies plagiarism but also states your specific concern (loss of creative learning interaction).

Provide a Way to Organize Your Main Points

A thesis statement should appear, almost verbatim, toward the end of the introduction to a speech. A thesis statement helps the audience get ready to listen to the arrangement of points that follow. Many speakers say that if they can create a strong thesis sentence, the rest of the speech tends to develop with relative ease. On the other hand, when the thesis statement is not very clear, creating a speech is an uphill battle.

When your thesis statement is sufficiently clear and decisive, you will know where you stand about your topic and where you intend to go with your speech. Having a clear thesis statement is especially important if you know a great deal about your topic or you have strong feelings about it. If this is the case for you, you need to know exactly what you are planning on talking about in order to fit within specified time limitations. Knowing where you are and where you are going is the entire point in establishing a thesis statement; it makes your speech much easier to prepare and to present.

Let’s say you have a fairly strong thesis statement, and that you’ve already brainstormed a list of information that you know about the topic. Chances are your list is too long and has no focus. Using your thesis statement, you can select only the information that (1) is directly related to the thesis and (2) can be arranged in a sequence that will make sense to the audience and will support the thesis. In essence, a strong thesis statement helps you keep useful information and weed out less useful information.

Make Your Research More Effective

If you begin your research with only a general topic in mind, you run the risk of spending hours reading mountains of excellent literature about your topic. However, mountains of literature do not always make coherent speeches. You may have little or no idea of how to tie your research all together, or even whether you should tie it together. If, on the other hand, you conduct your research with a clear thesis statement in mind, you will be better able to zero in only on material that directly relates to your chosen thesis statement. Let’s look at an example that illustrates this point:

Many traffic accidents involve drivers older than fifty-five.

While this statement may be true, you could find industrial, medical, insurance literature that can drone on ad infinitum about the details of all such accidents in just one year. Instead, focusing your thesis statement will help you narrow the scope of information you will be searching for while gathering information. Here’s an example of a more focused thesis statement:

Three factors contribute to most accidents involving drivers over fifty-five years of age: failing eyesight, slower reflexes, and rapidly changing traffic conditions.

This framing is somewhat better. This thesis statement at least provides three possible main points and some keywords for your electronic catalog search. However, if you want your audience to understand the context of older people at the wheel, consider something like:

Mature drivers over fifty-five years of age must cope with more challenging driving conditions than existed only one generation ago: more traffic moving at higher speeds, the increased imperative for quick driving decisions, and rapidly changing ramp and cloverleaf systems. Because of these challenges, I want my audience to believe that drivers over the age of sixty-five should be required to pass a driving test every five years.

This framing of the thesis provides some interesting choices. First, several terms need to be defined, and these definitions might function surprisingly well in setting the tone of the speech. Your definitions of words like “generation,” “quick driving decisions,” and “cloverleaf systems” could jolt your audience out of assumptions they have taken for granted as truth.

Second, the framing of the thesis provides you with a way to describe the specific changes as they have occurred between, say, 1970 and 2010. How much, and in what ways, have the volume and speed of traffic changed? Why are quick decisions more critical now? What is a “cloverleaf,” and how does any driver deal cognitively with exiting in the direction seemingly opposite to the desired one? Questions like this, suggested by your own thesis statement, can lead to a strong, memorable speech.

Enhance Your Delivery

When your thesis is not clear to you, your listeners will be even more clueless than you are—but if you have a good clear thesis statement, your speech becomes clear to your listeners. When you stand in front of your audience presenting your introduction, you can vocally emphasize the essence of your speech, expressed as your thesis statement. Many speakers pause for a half second, lower their vocal pitch slightly, slow down a little, and deliberately present the thesis statement, the one sentence that encapsulates its purpose. When this is done effectively, the purpose, intent, or main idea of a speech is driven home for an audience.

How to Write a Thesis Statement

Now that we’ve looked at why a thesis statement is crucial in a speech, let’s switch gears and talk about how we go about writing a solid thesis statement. A thesis statement is related to the general and specific purposes of a speech as we discussed them in Chapter 6 “Finding a Purpose and Selecting a Topic” .

Choose Your Topic

The first step in writing a good thesis statement was originally discussed in Chapter 6 “Finding a Purpose and Selecting a Topic” when we discussed how to find topics. Once you have a general topic, you are ready to go to the second step of creating a thesis statement.

Narrow Your Topic

One of the hardest parts of writing a thesis statement is narrowing a speech from a broad topic to one that can be easily covered during a five- to ten-minute speech. While five to ten minutes may sound like a long time to new public speakers, the time flies by very quickly when you are speaking. You can easily run out of time if your topic is too broad. To ascertain if your topic is narrow enough for a specific time frame, ask yourself three questions.

First, is your thesis statement narrow or is it a broad overgeneralization of a topic? An overgeneralization occurs when we classify everyone in a specific group as having a specific characteristic. For example, a speaker’s thesis statement that “all members of the National Council of La Raza are militant” is an overgeneralization of all members of the organization. Furthermore, a speaker would have to correctly demonstrate that all members of the organization are militant for the thesis statement to be proven, which is a very difficult task since the National Council of La Raza consists of millions of Hispanic Americans. A more appropriate thesis related to this topic could be, “Since the creation of the National Council of La Raza [NCLR] in 1968, the NCLR has become increasingly militant in addressing the causes of Hispanics in the United States.”

The second question to ask yourself when narrowing a topic is whether your speech’s topic is one clear topic or multiple topics. A strong thesis statement consists of only a single topic. The following is an example of a thesis statement that contains too many topics: “Medical marijuana, prostitution, and gay marriage should all be legalized in the United States.” Not only are all three fairly broad, but you also have three completely unrelated topics thrown into a single thesis statement. Instead of a thesis statement that has multiple topics, limit yourself to only one topic. Here’s an example of a thesis statement examining only one topic: “Today we’re going to examine the legalization and regulation of the oldest profession in the state of Nevada.” In this case, we’re focusing our topic to how one state has handled the legalization and regulation of prostitution.

The last question a speaker should ask when making sure a topic is sufficiently narrow is whether the topic has direction. If your basic topic is too broad, you will never have a solid thesis statement or a coherent speech. For example, if you start off with the topic “Barack Obama is a role model for everyone,” what do you mean by this statement? Do you think President Obama is a role model because of his dedication to civic service? Do you think he’s a role model because he’s a good basketball player? Do you think he’s a good role model because he’s an excellent public speaker? When your topic is too broad, almost anything can become part of the topic. This ultimately leads to a lack of direction and coherence within the speech itself. To make a cleaner topic, a speaker needs to narrow her or his topic to one specific area. For example, you may want to examine why President Obama is a good speaker.

Put Your Topic into a Sentence

Once you’ve narrowed your topic to something that is reasonably manageable given the constraints placed on your speech, you can then formalize that topic as a complete sentence. For example, you could turn the topic of President Obama’s public speaking skills into the following sentence: “Because of his unique sense of lyricism and his well-developed presentational skills, President Barack Obama is a modern symbol of the power of public speaking.” Once you have a clear topic sentence, you can start tweaking the thesis statement to help set up the purpose of your speech.

Add Your Argument, Viewpoint, or Opinion

This function only applies if you are giving a speech to persuade. If your topic is informative, your job is to make sure that the thesis statement is nonargumentative and focuses on facts. For example, in the preceding thesis statement we have a couple of opinion-oriented terms that should be avoided for informative speeches: “unique sense,” “well-developed,” and “power.” All three of these terms are laced with an individual’s opinion, which is fine for a persuasive speech but not for an informative speech. For informative speeches, the goal of a thesis statement is to explain what the speech will be informing the audience about, not attempting to add the speaker’s opinion about the speech’s topic. For an informative speech, you could rewrite the thesis statement to read, “This speech is going to analyze Barack Obama’s use of lyricism in his speech, ‘A World That Stands as One,’ delivered July 2008 in Berlin.”

On the other hand, if your topic is persuasive, you want to make sure that your argument, viewpoint, or opinion is clearly indicated within the thesis statement. If you are going to argue that Barack Obama is a great speaker, then you should set up this argument within your thesis statement.

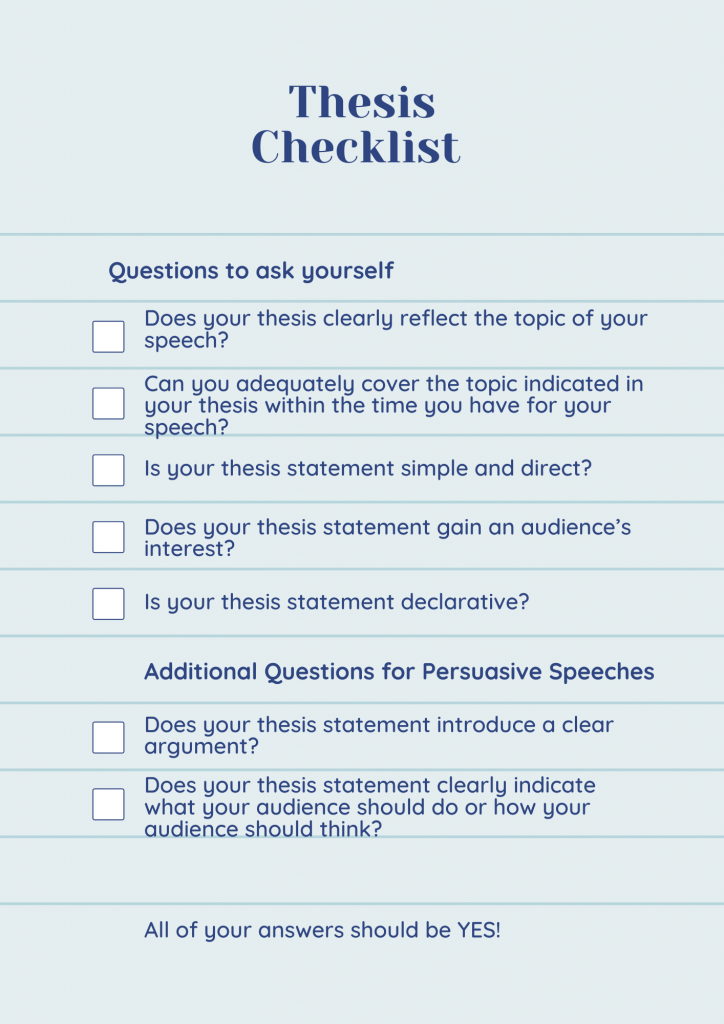

Use the Thesis Checklist

Once you have written a first draft of your thesis statement, you’re probably going to end up revising your thesis statement a number of times prior to delivering your actual speech. A thesis statement is something that is constantly tweaked until the speech is given. As your speech develops, often your thesis will need to be rewritten to whatever direction the speech itself has taken. We often start with a speech going in one direction, and find out through our research that we should have gone in a different direction. When you think you finally have a thesis statement that is good to go for your speech, take a second and make sure it adheres to the criteria shown in Table 9.1 “Thesis Checklist”

Table 9.1 Thesis Checklist

Preview of Speech

The final part of an introduction contains a preview of the major points to be covered within your speech. I’m sure we’ve all seen signs that have three cities listed on them with the mileage to reach each city. This mileage sign is an indication of what is to come. A preview works the same way. A preview foreshadows what the main body points will be in the speech. For example, to preview a speech on bullying in the workplace, one could say, “To understand the nature of bullying in the modern workplace, I will first define what workplace bullying is and the types of bullying, I will then discuss the common characteristics of both workplace bullies and their targets, and lastly, I will explore some possible solutions to workplace bullying.” In this case, each of the phrases mentioned in the preview would be a single distinct point made in the speech itself. In other words, the first major body point in this speech would examine what workplace bullying is and the types of bullying; the second major body point in this speech would discuss the common characteristics of both workplace bullies and their targets; and lastly, the third body point in this speech would explore some possible solutions to workplace bullying.

Key Takeaways

- Linking the attention-getter to the speech topic is essential so that you maintain audience attention and so that the relevance of the attention-getter is clear to your audience.

- Establishing how your speech topic is relevant and important shows the audience why they should listen to your speech.

- To be an effective speaker, you should convey all three components of credibility, competence, trustworthiness, and caring/goodwill, by the content and delivery of your introduction.

- A clear thesis statement is essential to provide structure for a speaker and clarity for an audience.

- An effective preview identifies the specific main points that will be present in the speech body.

- Make a list of the attention-getting devices you might use to give a speech on the importance of recycling. Which do you think would be most effective? Why?

- Create a thesis statement for a speech related to the topic of collegiate athletics. Make sure that your thesis statement is narrow enough to be adequately covered in a five- to six-minute speech.

- Discuss with a partner three possible body points you could utilize for the speech on the topic of volunteerism.

- Fill out the introduction worksheet to help work through your introduction for your next speech. Please make sure that you answer all the questions clearly and concisely.

Stand up, Speak out Copyright © 2016 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Module 4: Organizing and Outlining

The topic, purpose, and thesis.

Before any work can be done on crafting the body of your speech or presentation, you must first do some prep work—selecting a topic, formulating a purpose statement, and crafting a thesis statement. In doing so, you lay the foundation for your speech by making important decisions about what you will speak about and for what purpose you will speak. These decisions will influence and guide the entire speechwriting process, so it is wise to think carefully and critically during these beginning stages.

I think reading is important in any form. I think a person who’s trying to learn to like reading should start off reading about a topic they are interested in, or a person they are interested in. – Ice Cube

Questions for Selecting a Topic

- What important events are occurring locally, nationally and internationally?

- What do I care about most?

- Is there someone or something I can advocate for?

- What makes me angry/happy?

- What beliefs/attitudes do I want to share?

- Is there some information the audience needs to know?

Selecting a Topic

“The Reader” by Shakespearesmonkey. CC-BY-NC .

Generally, speakers focus on one or more interrelated topics—relatively broad concepts, ideas, or problems that are relevant for particular audiences. The most common way that speakers discover topics is by simply observing what is happening around them—at their school, in their local government, or around the world. This is because all speeches are brought into existence as a result of circumstances, the multiplicity of activities going on at any one given moment in a particular place. For instance, presidential candidates craft short policy speeches that can be employed during debates, interviews, or town hall meetings during campaign seasons. When one of the candidates realizes he or she will not be successful, the particular circumstances change and the person must craft different kinds of speeches—a concession speech, for example. In other words, their campaign for presidency, and its many related events, necessitates the creation of various speeches. Rhetorical theorist Lloyd Bitzer [1] describes this as the rhetorical situation. Put simply, the rhetorical situation is the combination of factors that make speeches and other discourse meaningful and a useful way to change the way something is. Student government leaders, for example, speak or write to other students when their campus is facing tuition or fee increases, or when students have achieved something spectacular, like lobbying campus administrators for lower student fees and succeeding. In either case, it is the situation that makes their speeches appropriate and useful for their audience of students and university employees. More importantly, they speak when there is an opportunity to change a university policy or to alter the way students think or behave in relation to a particular event on campus.

But you need not run for president or student government in order to give a meaningful speech. On the contrary, opportunities abound for those interested in engaging speech as a tool for change. Perhaps the simplest way to find a topic is to ask yourself a few questions. See the textbox entitled “Questions for Selecting a Topic” for a few questions that will help you choose a topic.

There are other questions you might ask yourself, too, but these should lead you to at least a few topical choices. The most important work that these questions do is to locate topics within your pre-existing sphere of knowledge and interest. David Zarefsky [2] also identifies brainstorming as a way to develop speech topics, a strategy that can be helpful if the questions listed in the textbox did not yield an appropriate or interesting topic.

Starting with a topic you are already interested in will likely make writing and presenting your speech a more enjoyable and meaningful experience. It means that your entire speechwriting process will focus on something you find important and that you can present this information to people who stand to benefit from your speech.

Once you have answered these questions and narrowed your responses, you are still not done selecting your topic. For instance, you might have decided that you really care about conserving habitat for bog turtles. This is a very broad topic and could easily lead to a dozen different speeches. To resolve this problem, speakers must also consider the audience to whom they will speak, the scope of their presentation, and the outcome they wish to achieve. If the bog turtle enthusiast knows that she will be talking to a local zoning board and that she hopes to stop them from allowing businesses to locate on important bog turtle habitat, her topic can easily morph into something more specific. Now, her speech topic is two-pronged: bog turtle habitat and zoning rules.

Formulating the Purpose Statements

“Bog turtle sunning” by U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Public domain.

By honing in on a very specific topic, you begin the work of formulating your purpose statement . In short, a purpose statement clearly states what it is you would like to achieve. Purpose statements are especially helpful for guiding you as you prepare your speech. When deciding which main points, facts, and examples to include, you should simply ask yourself whether they are relevant not only to the topic you have selected, but also whether they support the goal you outlined in your purpose statement. The general purpose statement of a speech may be to inform, to persuade, to inspire, to celebrate, to mourn, or to entertain. Thus, it is common to frame a specific purpose statement around one of these goals. According to O’Hair, Stewart, and Rubenstein, a specific purpose statement “expresses both the topic and the general speech purpose in action form and in terms of the specific objectives you hope to achieve.” [3] For instance, the bog turtle habitat activist might write the following specific purpose statement: At the end of my speech, the Clarke County Zoning Commission will understand that locating businesses in bog turtle habitat is a poor choice with a range of negative consequences. In short, the general purpose statement lays out the broader goal of the speech while the specific purpose statement describes precisely what the speech is intended to do.

Success demands singleness of purpose. – Vince Lombardi

Writing the Thesis Statement

The specific purpose statement is a tool that you will use as you write your talk, but it is unlikely that it will appear verbatim in your speech. Instead, you will want to convert the specific purpose statement into a thesis statement that you will share with your audience. A thesis statement encapsulates the main points of a speech in just a sentence or two, and it is designed to give audiences a quick preview of what the entire speech will be about. The thesis statement for a speech, like the thesis of a research- based essay, should be easily identifiable and ought to very succinctly sum up the main points you will present. Moreover, the thesis statement should reflect the general purpose of your speech; if your purpose is to persuade or educate, for instance, the thesis should alert audience members to this goal. The bog turtle enthusiast might prepare the following thesis statement based on her specific purpose statement: Bog turtle habitats are sensitive to a variety of activities, but land development is particularly harmful to unstable habitats. The Clarke County Zoning Commission should protect bog turtle habitats by choosing to prohibit business from locating in these habitats. In this example, the thesis statement outlines the main points and implies that the speaker will be arguing for certain zoning practices.

Candela Citations

- Chapter 8 The Topic, Purpose, and Thesis. Authored by : Joshua Trey Barnett. Provided by : University of Indiana, Bloomington, IN. Located at : http://publicspeakingproject.org/psvirtualtext.html . Project : The Public Speaking Project. License : CC BY-NC-ND: Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives

- The Reader. Authored by : Shakespearesmonkey. Located at : https://www.flickr.com/photos/shakespearesmonkey/4939289974/ . License : CC BY-NC: Attribution-NonCommercial

- Image of a bog turtle . Authored by : R. G. Tucker, Jr.. Provided by : United States Fish and Wildlife Service. Located at : http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bog_turtle_sunning.jpg . License : Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Bitzer, L. (1968). The rhetorical situation. Philosophy & Rhetoric , 1 (1), 1 – 14. ↵

- Zarefsky, D. (2010). Public speaking: Strategies for success (6th edition). Boston: Allyn & Bacon. ↵

- O’Hair, D., Stewart, R., Rubenstein, H. (2004). A speaker’s guidebook: Text and reference (2nd edition). Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s. ↵

Privacy Policy

Speechwriting

8 Purpose and Thesis

Speechwriting Essentials

In this chapter . . .

As discussed in the chapter on Speaking Occasion , speechwriting begins with careful analysis of the speech occasion and its given circumstances, leading to the choice of an appropriate topic. As with essay writing, the early work of speechwriting follows familiar steps: brainstorming, research, pre-writing, thesis, and so on.

This chapter focuses on techniques that are unique to speechwriting. As a spoken form, speeches must be clear about the purpose and main idea or “takeaway.” Planned redundancy means that you will be repeating these elements several times over during the speech.

Furthermore, finding purpose and thesis are essential whether you’re preparing an outline for extemporaneous delivery or a completely written manuscript for presentation. When you know your topic, your general and specific purpose, and your thesis or central idea, you have all the elements you need to write a speech that is focused, clear, and audience friendly.

Recognizing the General Purpose

Speeches have traditionally been grouped into one of three categories according to their primary purpose: 1) to inform, 2) to persuade, or 3) to inspire, honor, or entertain. These broad goals are commonly known as the general purpose of a speech . Earlier, you learned about the actor’s tool of intention or objectives. The general purpose is like a super-objective; it defines the broadest goal of a speech. These three purposes are not necessarily exclusive to the others. A speech designed to be persuasive can also be informative and entertaining. However, a speech should have one primary goal. That is its general purpose.

Why is it helpful to talk about speeches in such broad terms? Being perfectly clear about what you want your speech to do or make happen for your audience will keep you focused. You can make a clearer distinction between whether you want your audience to leave your speech knowing more (to inform), or ready to take action (to persuade), or feeling something (to inspire)

It’s okay to use synonyms for these broad categories. Here are some of them:

- To inform could be to explain, to demonstrate, to describe, to teach.

- To persuade could be to convince, to argue, to motivate, to prove.

- To inspire might be to honor, or entertain, to celebrate, to mourn.

In summary, the first question you must ask yourself when starting to prepare a speech is, “Is the primary purpose of my speech to inform, to persuade, or to inspire?”

Articulating Specific Purpose

A specific purpose statement builds upon your general purpose and makes it specific (as the name suggests). For example, if you have been invited to give a speech about how to do something, your general purpose is “to inform.” Choosing a topic appropriate to that general purpose, you decide to speak about how to protect a personal from cyberattacks. Now you are on your way to identifying a specific purpose.

A good specific purpose statement has three elements: goal, target audience, and content.

If you think about the above as a kind of recipe, then the first two “ingredients” — your goal and your audience — should be simple. Words describing the target audience should be as specific as possible. Instead of “my peers,” you could say, for example, “students in their senior year at my university.”

The third ingredient in this recipe is content, or what we call the topic of your speech. This is where things get a bit difficult. You want your content to be specific and something that you can express succinctly in a sentence. Here are some common problems that speakers make in defining the content, and the fix:

Now you know the “recipe” for a specific purpose statement. It’s made up of T o, plus an active W ord, a specific A udience, and clearly stated C ontent. Remember this formula: T + W + A + C.

A: for a group of new students

C: the term “plagiarism”

Here are some further examples a good specific purpose statement:

- To explain to a group of first-year students how to join a school organization.

- To persuade the members of the Greek society to take a spring break trip in Daytona Beach.

- To motivate my classmates in English 101 to participate in a study abroad program.

- To convince first-year students that they need at least seven hours of sleep per night to do well in their studies.

- To inspire my Church community about the accomplishments of our pastor.

The General and Specific Purpose Statements are writing tools in the sense that they help you, as a speechwriter, clarify your ideas.

Creating a Thesis Statement

Once you are clear about your general purpose and specific purpose, you can turn your attention to crafting a thesis statement. A thesis is the central idea in an essay or a speech. In speechwriting, the thesis or central idea explains the message of the content. It’s the speech’s “takeaway.” A good thesis statement will also reveal and clarify the ideas or assertions you’ll be addressing in your speech (your main points). Consider this example:

General Purpose: To persuade. Specific Purpose: To motivate my classmates in English 101 to participate in a study abroad program. Thesis: A semester-long study abroad experience produces lifelong benefits by teaching you about another culture, developing your language skills, and enhancing your future career prospects.

The difference between a specific purpose statement and a thesis statement is clear in this example. The thesis provides the takeaway (the lifelong benefits of study abroad). It also points to the assertions that will be addressed in the speech. Like the specific purpose statement, the thesis statement is a writing tool. You’ll incorporate it into your speech, usually as part of the introduction and conclusion.

All good expository, rhetorical, and even narrative writing contains a thesis. Many students and even experienced writers struggle with formulating a thesis. We struggle when we attempt to “come up with something” before doing the necessary research and reflection. A thesis only becomes clear through the thinking and writing process. As you develop your speech content, keep asking yourself: What is important here? If the audience can remember only one thing about this topic, what do I want them to remember?

Example #2: General Purpose: To inform Specific Purpose: To demonstrate to my audience the correct method for cleaning a computer keyboard. Central Idea: Your computer keyboard needs regular cleaning to function well, and you can achieve that in four easy steps.

Example # 3 General Purpose: To Inform Specific Purpose: To describe how makeup is done for the TV show The Walking Dead . Central Idea: The wildly popular zombie show The Walking Dead achieves incredibly scary and believable makeup effects, and in the next few minutes I will tell you who does it, what they use, and how they do it.

Notice in the examples above that neither the specific purpose nor the central idea ever exceeds one sentence. If your central idea consists of more than one sentence, then you are probably including too much information.

Problems to Avoid

The first problem many students have in writing their specific purpose statement has already been mentioned: specific purpose statements sometimes try to cover far too much and are too broad. For example:

“To explain to my classmates the history of ballet.”

Aside from the fact that this subject may be difficult for everyone in your audience to relate to, it’s enough for a three-hour lecture, maybe even a whole course. You’ll probably find that your first attempt at a specific purpose statement will need refining. These examples are much more specific and much more manageable given the limited amount of time you’ll have.

- To explain to my classmates how ballet came to be performed and studied in the U.S.

- To explain to my classmates the difference between Russian and French ballet.

- To explain to my classmates how ballet originated as an art form in the Renaissance.

- To explain to my classmates the origin of the ballet dancers’ clothing.

The second problem happens when the “communication verb” in the specific purpose does not match the content; for example, persuasive content is paired with “to inform” or “to explain.” Can you find the errors in the following purpose statements?

- To inform my audience why capital punishment is unconstitutional. (This is persuasive. It can’t be informative since it’s taking a side)

- To persuade my audience about the three types of individual retirement accounts. (Even though the purpose statement says “persuade,” it isn’t persuading the audience of anything. It is informative.)

- To inform my classmates that Universal Studios is a better theme park than Six Flags over Georgia. (This is clearly an opinion; hence it is a persuasive speech and not merely informative)

The third problem exists when the content part of the specific purpose statement has two parts. One specific purpose is enough. These examples cover two different topics.

- To explain to my audience how to swing a golf club and choose the best golf shoes.

- To persuade my classmates to be involved in the Special Olympics and vote to fund better classes for the intellectually disabled.

To fix this problem of combined or hybrid purposes, you’ll need to select one of the topics in these examples and speak on that one alone.

The fourth problem with both specific purpose and central idea statements is related to formatting. There are some general guidelines that need to be followed in terms of how you write out these elements of your speech:

- Don’t write either statement as a question.

- Always use complete sentences for central idea statements and infinitive phrases (beginning with “to”) for the specific purpose statement.

- Use concrete language (“I admire Beyoncé for being a talented performer and businesswoman”) and avoid subjective or slang terms (“My speech is about why I think Beyoncé is the bomb”) or jargon and acronyms (“PLA is better than CBE for adult learners.”)

There are also problems to avoid in writing the central idea statement. As mentioned above, remember that:

- The specific purpose and central idea statements are not the same thing, although they are related.

- The central idea statement should be clear and not complicated or wordy; it should “stand out” to the audience. As you practice delivery, you should emphasize it with your voice.

- The central idea statement should not be the first thing you say but should follow the steps of a good introduction as outlined in the next chapters.

You should be aware that all aspects of your speech are constantly going to change as you move toward the moment of giving your speech. The exact wording of your central idea may change, and you can experiment with different versions for effectiveness. However, your specific purpose statement should not change unless there is a good reason to do so. There are many aspects to consider in the seemingly simple task of writing a specific purpose statement and its companion, the central idea statement. Writing good ones at the beginning will save you some trouble later in the speech preparation process.

Public Speaking as Performance Copyright © 2023 by Mechele Leon is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Crafting a Thesis Statement and Preview

Crafting a thesis statement.

A thesis statement is a short, declarative sentence that states the purpose, intent, or main idea of a speech. A strong, clear thesis statement is very valuable within an introduction because it lays out the basic goal of the entire speech. We strongly believe that it is worthwhile to invest some time in framing and writing a good thesis statement. You may even want to write your thesis statement before you even begin conducting research for your speech. While you may end up rewriting your thesis statement later, having a clear idea of your purpose, intent, or main idea before you start searching for research will help you focus on the most appropriate material. To help us understand thesis statements, we will first explore their basic functions and then discuss how to write a thesis statement.

Basic Functions of a Thesis Statement