We use cookies to enhance our website for you. Proceed if you agree to this policy or learn more about it.

- Essay Database >

- Essay Examples >

- Essays Topics >

- Essay on Global Warming

Argumentative Essay On Toulmin Model Global Warming

Type of paper: Argumentative Essay

Topic: Global Warming , Pollution , World , Evidence , Nature , Development , Environmental Issues , Environment

Words: 2750

Published: 12/12/2019

ORDER PAPER LIKE THIS

Outline This essay will look at the issue of global warming using the Toulmin model (Toulmin, 1; Fullerton.edu, 1). As such, the following sections will be discussed in the essay in line with the model: Claim: Looking at the issue of global warming, it is clear that there are many causes culminating into the pollution of the environment, and the degradation of the ozone layer. There are various factors that can lead to this. The end result is global warming which threatens life on the planet. As such, it is the responsibility of the inhabitants of earth to stop this catastrophe. This essay therefore claims that man has contributed to global warming and holds the key to stopping it. Grounds: This is where the essay will seek to prove that man has actually participated in propelling global warming. It will therefore provide evidence and facts that prove that man’s activities have in one way or another led to the disruption in the cause of nature. As such, his activities lead to global warming and climate change. It will also seek to give evidence that if man changed his ways and put in place some measures, he could as well help in controlling this catastrophe. The grounds will be based on two major arguments and the evidence for them: that man’s activities have greatly contributed to global warming and two, that a change in the order that man does things would go a long way in saving the environment from total degradation. Warrants: in this section, the essay will seek to prove or show the actual relationship between man’s activities and the degradation of the environment. In other words, this is where a correlation will be drawn between the role of man and global warming. Once the link is established, the essay will then prove that if man reversed the order in which he carried out his activities, then the same would be reflected on the environment, thus reducing the pollution rates. Backing: this is where hard evidence will be given for the argument. In this section, the essay will seek to provide some facts through statistical and scientific evidence to show how man has contributed to environmental degradation. For instance, it will provide statistics on the emission rates of carbon dioxide and how these contribute to global warming. It will also give evidence on the various effects of global warming on life in the planet. This is expected to give a strong founding for the essay. Modal Qualifiers: Toulmin (340) observes that in this section, the essay should give evidence that the proposed action would be universally accepted and would not have any negative impacts on the people or the environment. As such, this essay will seek to show that the proposed mitigation measures could go a long way in saving the whole world from the dangers of environmental change. Rebuttal: This is the essay section that will deal with a counter argument on the issue of man’s contribution to causing and preventing environmental degradation. In this section, the essay will seek to prove that there are various causes that lead to global warming, some of which are natural. Since man has no control over the natural events, this argument will be used to prove that man can do nothing to cause or control the process of environmental degradation and global warming. It will seek to show that man is an observer who does nothing but cope with all the environmental challenges that Mother Nature brings along his way.

Claim The issue of global warming is a global concern that has put the leaders of the world in a tight position to find a solution for the climate change issue that is threatening the life on earth. According to the National Geographic (1), these worries are justified. This is mainly because the temperatures on the earth’s surface seem to be rising day in day out. As a result, the levels of the seas are rising and the glaciers in the high peaks on earth as well as the Polar Regions are gradually melting. This poses the threat of an even greater rise in the sea levels. On overall assessment, it emerges quite clearly that man has a great significance to the environmental issues. He has the ability to cause a total disruption of the environment just as he has the ability to control it. As such, it is upon man to decide on what he wants to do with his environment.

There is sufficient evidence to show that man has contributed to the course of environmental pollution which has ultimately led to global warming. There are some activities that man engage in that lead to increased emission. For instance, there is the use of motor vehicles. The car exhaust system leads to emission of carbon dioxide which leads to accumulation of the gas into the atmosphere (Strasburg, 1). Similarly, man, as he seeks comfort, ends up using some home devices that contribute to the release of green house gases. These are appliances such as the air conditioners. However, the greatest contribution that man has to the problem is the through industrial processes. Man engages in various processes that lead to the accumulation of these gases into the atmosphere (Citidata.com, 1; Dick, 1).

Of course, there are adverse effects of these activities to the life of plants and animals on the planet such as change in the weather patterns which affects productivity of the land, poses a threat to the animal habitat such as the polar bears and also poses health threats to man himself (nrdc.org, 1; Time for Change, 1). Due to these effects, man has to derive a way to solve the problem.

There are various ways in which man can achieve this. For instance, he can reduce engagement in activities that increase the pollution. For instance, he can use cars that have good engines, leading to proper utilization of fuel hence reduce the emission rates. Similarly, he can reform his industries so become more environmental friendly. For instance, he can find ways to detoxify gases released from the industrial chimneys before they are released into the atmosphere. Other changes can be made in the manner in which the processing industries go about their work so that they can reduce the emission rates (Global warming Facts, 1; Sierra Club, 1). Use of renewable energy could also go a long way in ensuring that the emission is reduced.

So far, the essay has shown that there are various activities that man can be engaged in to prevent the pollution of the environment. However, this does not specifically mean that if man observes the recommendations so far the issue of global warming would be solved. As such, there is need for sufficient evidence to prove that his activities can actually lead to the end of the problem.

This is the rational for this argument: the natural balance has been in existence for quite a long time. Man’s activities led to the disruption in the balance. As such, since man is the problem, he can as well be the solution by putting in place measures to restore the balance that he contributed in distorting. These are the measures indicated by Sierra Club (1) which include processes such as reducing waste materials, reusing some of the materials and recycling others. This would go a long way in ensuring that the ecological balance is maintained.

Other man’s activities lead to over-exploitation of the available resources, which again leads to the degradation of the environment. As such, if man put into place measures to control such effects, then there is a possibility that he could lead to a stop to the environmental threat. In conclusion, this section has sought to show the exact relation between man’s activities and global warming. It has emerged that there is a very strong correlation between the two. As such, if man controlled his activities, there is every possibility that this would be an efficient way of controlling the global warming process.

In this section, the main aim is to prove that there are various changes that ma can put in place to ensure that global warming is brought to a slow. First of all, it is important to look at the current trend in global warming. The national Geographic (1) indicates that the average temperatures on the earth’s surface have gone up by 1.4 degrees Fahrenheit, which is about 0.8 degrees Celsius. If this is not brought to check, then the levels could continue rising which could lead to serious repercussions on the earth’s surface. The arctic regions are quickly wearing away and if the trend continues, then they could totally disappear by the summer of 2040, which is of course a threat to the life of animals living in these regions (nrdc.org, 1).

On a similar note, the coral reefs are suffering bleaching effect due to the change in water temperatures, where some have recorded bleaching rates of as high as 70%. Glaciers and mountain snows are also receiving the blunt end of the global warming effects where, for instance, the Glacier National Park has observed a reduction in the number of glaciers from 150 glaciers in 1910 to only 27 glaciers at the present. These statistics send a shocking wave to the environmentalists in the world. It is clear that unless something is done, then the world is doomed to suffer from the wrath of nature.

It is not the animals who have contributed to this disruption. Rather, it is the creature that is supposed to be the custodian of nature: man. However, since man knows the exact causes of the problem, he can as well contribute to ending the saga. All he has to do is reverse his manner of doing things so that they are more environmental friendly. He has the ability and means; all he needs is the will and the motivation to do it.

Modal Qualifiers

According to NASA (1), it comes out quite clearly that more often than not, man’s activities are concerned with the emission of green house gases which lead to the issue of global warming. For instance, man usually drives to and from work. It is very common to find that in one homestead there are more than one automobile. The meaning of this is that every time that the different members of the family go out, they usually lead to more emission. If the number of automobile per household was reduced, this could go a long way in curbing the issue of emission.

Sierra Club (1) observes that manufacturing industries are always releasing gases into the atmosphere. Of course, this goes a long way into polluting the environment and increasing the concentration of the GHG gases. Suppose these emission rates were cut down or controlled so that there is reduced accumulation of GHG gases into the atmosphere. The results would be gratifying for the whole world. There is also the issue of deforestation. Most of the time, man is involved in activities that lead to destruction of the forest cover in the world. Activities such as charcoal burning, clearing land for farming and overstocking contribute to making the land bare. This has serious repercussions on the environment since the trees contribute to the cleaning of air. As such, if man reduced the frequency at which he cuts down trees, then the gross effect would be conservation of the environment.

All along, this argument has held the position that man contribute to the environmental degradation that leads to global warming. Furthermore, it has stressed on the fact that if man changed the manner in which he interacted with his environment, there is a possibility that he could curb the global warming menace. This argument could be logical to some extent. However, there is another argument that shows that man has no control over global warming at all.

First of all, there is the scientific argument which claims that the green house gases are not the only pre-cursors to global warming. As such, in as much as man contributes to the release of these gases into the atmosphere, this has little or no effect on the rate of global warming (Dick, 1).

However, the strongest argument against man’s contribution towards the control of environmental pollution and global warming is the argument that most of the significant causes of global warming are natural (Strasburg, 1). For instance, there are the volcanic eruptions that lead to the rise in the temperature levels. As a matter of fact, there is no way that man has control over these volcanic activities. Therefore, he is left in a helpless situation where he just observes as the environmental and natural forces work to his disadvantage.

There are also other factors such as the water vapors. Day in day out, water from the water bodies around the world vaporizes into vapor which accumulates in the atmosphere and contributes to the global warming. There is no way that man has control over this and as such, he has no means to control it. The same case applies to the solar cycles and the cosmic rays which work together to bring an overall effect of global warming. The mechanism by which these forces work is far beyond the control of man (Sarsburg, 1).

This essay has looked at the Toulmin model and how it can be used in finding a solution for a problem. It has given the claim, grounds, warrant, backing, modal qualifiers as well as the rebuttal. The issue that has been addressed by the essay is global warming, where the essay sough to prove as to whether or not man has the ability to control the problem. The Toulmin model was followed all through the essay.

Works Cited

City-Data.com. ‘Man’s Contribution to Global Warming.’ 2012. Web, 26th March 2012, http://www.city-data.com/forum/green-living/605770-man-s-contribution-global-warming.html Dick, Phillip K. ‘Is Man Caused Global Warming a Scientific Fact?’ 2011. Web, 26th March 2012, http://lrak.net/globalwarming.htm Fullertion.edu. ‘Toulmin Model of Argument.’ N.d. Web, 26th March 2012, https://mail.google.com/mail/?shva=1#inbox/13647e25076a8d62 Global Warming Facts. ‘Global Warming.’ 2010. Web, 26th March 2012, http://globalwarming-facts.info/50-tips.html Nasa.gov. ‘Global Climate Change.’ 2012. Web, 26th March 2012, http://climate.nasa.gov/causes/ National Geographic News. ‘Global Warming Fast Facts.’ 1996. Web, 26th March 2012, http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2004/12/1206_041206_global_warming.html NRDC. ‘Consequences of Global Warming.’ 2012. Web, 26th March 2012, http://www.nrdc.org/globalwarming/fcons.asp Sierra Club. ‘Clean Energy Solutions: Ten Things You Can Do to Help Curb Global Warming.’ 2012. Web, 26th March 2012, http://www.sierraclub.org/energy/tenthings/default.aspx Strasburg, McIntire Jeff. ‘Top Global Warming Causes – Natural or Human?’ 2009. Web, 26th March 2012, http://blog.sustainablog.org/2009/06/the-top-causes-of-global-warming-natural-or-human/ Time for Change. ‘Cause and Effect for Global Warming.’ N.d. Web. 26th March 2012, http://timeforchange.org/cause-and-effect-for-global-warming Toulmin, S. ‘The Uses of Argument.’ 1969. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. Think Quest. ‘Global Warming.’ 2012. Web, 26th March 2012, http://library.thinkquest.org/CR0215471/global_warming.htm

Cite this page

Share with friends using:

Removal Request

Finished papers: 1530

This paper is created by writer with

If you want your paper to be:

Well-researched, fact-checked, and accurate

Original, fresh, based on current data

Eloquently written and immaculately formatted

275 words = 1 page double-spaced

Get your papers done by pros!

Other Pages

Meter research papers, john deere case studies, vietnam war course work, iraq course work, starbucks course work, parenting course work, industrialization course work, sculpture course work, award course work, athletes course work, telephone no literature review examples, racism in us essay sample, htc corporation report examples, individual cultural diversity issue and its relevance to workplace dynamics essay sample, kant case study example, koppen climate classification system essay examples, free book review about steve jobs, chief characteristics of postmodernism as described by lyotard and jameson essay samples, essay on following are the influences on business buyers, example of research paper on consumer models and and understanding of the manager 039 s problems, good example of research paper on effect of communication on interpersonal relations, good research paper on leadership interview project, berkleys position essay, good essay about decision analysis, good example of healthcare ethics essay, creative writing on social justice leader, marketing essays examples, laminar and turbulent pipe flow report, article review on chinese art and literature, quot essays, almon essays, scholars essays, air quality essays, proposals essays, new kind essays, third world countries essays, tourism sector essays, hacking essays, higher learning essays, institutions of higher learning essays, pertaining essays, headaches essays, rights movement essays.

Password recovery email has been sent to [email protected]

Use your new password to log in

You are not register!

By clicking Register, you agree to our Terms of Service and that you have read our Privacy Policy .

Now you can download documents directly to your device!

Check your email! An email with your password has already been sent to you! Now you can download documents directly to your device.

or Use the QR code to Save this Paper to Your Phone

The sample is NOT original!

Short on a deadline?

Don't waste time. Get help with 11% off using code - GETWOWED

No, thanks! I'm fine with missing my deadline

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Elements of Argument

9 Toulmin Argument Model

By liza long, amy minervini, and joel gladd.

Stephen Edelston Toulmin (born March 25, 1922) was a British philosopher, author, and educator. Toulmin devoted his works to analyzing moral reasoning. He sought to develop practical ways to evaluate ethical arguments effectively. The Toulmin Model of Argumentation, a diagram containing six interrelated components, was considered Toulmin’s most influential work, particularly in the fields of rhetoric, communication, and computer science. His components continue to provide useful means for analyzing arguments.

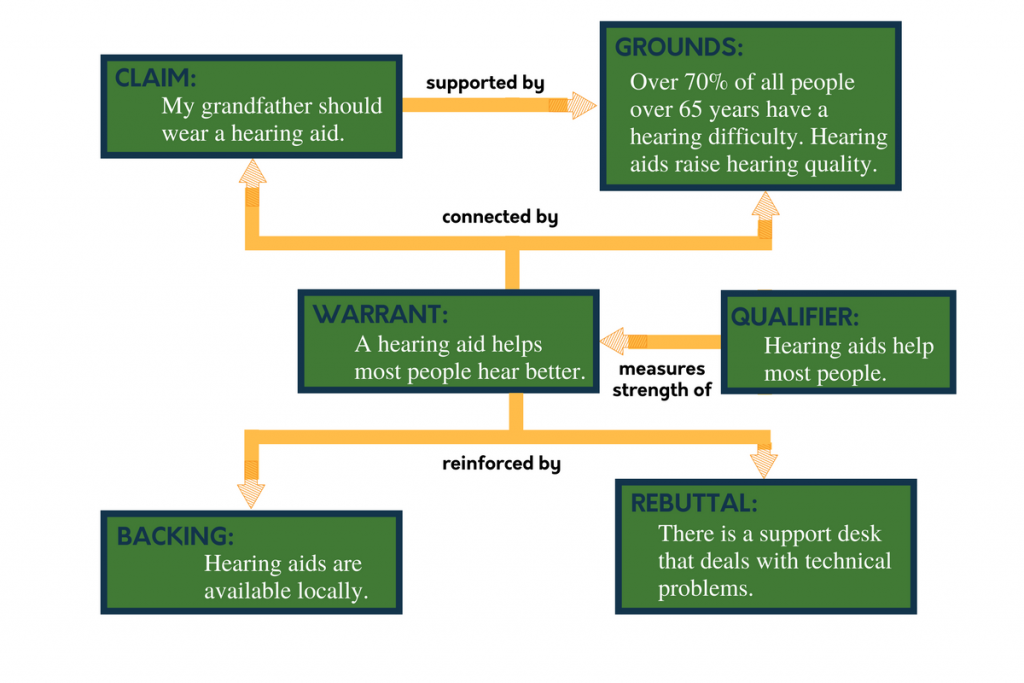

The following are the parts of a Toulmin argument (see Figure 9.1 for an example):

Claim: The claim is a statement that you are asking the other person to accept as true (i.e., a conclusion) and forms the nexus of the Toulmin argument because all the other parts relate back to the claim. The claim can include information and ideas you are asking readers to accept as true or actions you want them to accept and enact. One example of a claim is the following:

My grandfather should wear a hearing aid.

This claim both asks the reader to believe an idea and suggests an action to enact. However, like all claims, it can be challenged. Thus, a Toulmin argument does not end with a claim but also includes grounds and warrant to give support and reasoning to the claim.

Grounds: The grounds form the basis of real persuasion and include the reasoning behind the claim, data, and proof of expertise. Think of grounds as a combination of premises and support. The truth of the claim rests upon the grounds, so those grounds should be tested for strength, credibility, relevance, and reliability. The following are examples of grounds:

Over 70% of all people over 65 years have a hearing difficulty. Hearing aids raise hearing quality.

Information is usually a powerful element of persuasion, although it does affect people differently. Those who are dogmatic, logical, or rational will more likely be persuaded by factual data. Those who argue emotionally and who are highly invested in their own position will challenge it or otherwise try to ignore it. Thus, grounds can also include appeals to emotion, provided they aren’t misused. The best arguments, however, use a variety of support and rhetorical appeals.

Warrant: A warrant links data and other grounds to a claim, legitimizing the claim by showing the grounds to be relevant. The warrant may be carefully explained and explicit or unspoken and implicit. The warrant answers the question, “Why does that data mean your claim is true?” For example,

A hearing aid helps most people hear better.

The warrant may be simple, and it may also be a longer argument with additional sub-elements including those described below. Warrants may be based on logos, ethos or pathos, or values that are assumed to be shared with the listener. In many arguments, warrants are often implicit and, hence, unstated. This gives space for the other person to question and expose the warrant, perhaps to show it is weak or unfounded.

Backing: The backing for an argument gives additional support to the warrant. Backing can be confused with grounds, but the main difference is this: grounds should directly support the premises of the main argument itself, while backing exists to help the warrants make more sense. For example,

Hearing aids are available locally.

This statement works as backing because it gives credence to the warrant stated above, that a hearing aid will help most people hear better. The fact that hearing aids are readily available makes the warrant even more reasonable.

Qualifier: The qualifier indicates how the data justifies the warrant and may limit how universally the claim applies. The necessity of qualifying words comes from the plain fact that most absolute claims are ultimately false (all women want to be mothers, e.g.) because one counterexample sinks them immediately. Thus, most arguments need some sort of qualifier, words that temper an absolute claim and make it more reasonable. Common qualifiers include “most,” “usually,” “always,” or “sometimes.” For example,

Hearing aids help most people.

The qualifier “most” here allows for the reasonable understanding that rarely does one thing (a hearing aid) universally benefit all people. Another variant is the reservation, which may give the possibility of the claim being incorrect:

Unless there is evidence to the contrary, hearing aids do no harm to ears.

Qualifiers and reservations can be used to bolster weak arguments, so it is important to recognize them. They are often used by advertisers who are constrained not to lie. Thus, they slip “usually,” “virtually,” “unless,” and so on into their claims to protect against liability. While this may seem like sneaky practice, and it can be for some advertisers, it is important to note that the use of qualifiers and reservations can be a useful and legitimate part of an argument.

Rebuttal: Despite the careful construction of the argument, there may still be counterarguments that can be used. These may be rebutted either through a continued dialogue, or by pre-empting the counter-argument by giving the rebuttal during the initial presentation of the argument. For example, if you anticipated a counterargument that hearing aids, as a technology, may be fraught with technical difficulties, you would include a rebuttal to deal with that counterargument:

There is a support desk that deals with technical problems.

Any rebuttal is an argument in itself, and thus may include a claim, warrant, backing, and the other parts of the Toulmin structure.

Even if you do not wish to write an essay using strict Toulmin structure, using the Toulmin checklist can make an argument stronger. When first proposed, Toulmin based his layout on legal arguments, intending it to be used analyzing arguments typically found in the courtroom; in fact, Toulmin did not realize that this layout would be applicable to other fields until later. The first three elements–“claim,” “grounds,” and “warrant”–are considered the essential components of practical arguments, while the last three—“qualifier,” “backing,” and “rebuttal”—may not be necessary for all arguments.

Toulmin Exercise

Find an argument in essay form and diagram it using the Toulmin model. The argument can come from an Op-Ed article in a newspaper or a magazine think piece or a scholarly journal. See if you can find all six elements of the Toulmin argument. Use the structure above to diagram your article’s argument.

Attributions

“Toulmin Argument Model” by Liza Long, Amy Minervini, and Joel Gladd is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Writing Arguments in STEM Copyright © by Jason Peters; Jennifer Bates; Erin Martin-Elston; Sadie Johann; Rebekah Maples; Anne Regan; and Morgan White is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Feedback/errata.

Comments are closed.

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Toulmin Argument

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

What is the Toulmin Method?

Developed by philosopher Stephen E. Toulmin, the Toulmin method is a style of argumentation that breaks arguments down into six component parts: claim, grounds, warrant, qualifier, rebuttal, and backing . In Toulmin’s method, every argument begins with three fundamental parts: the claim, the grounds, and the warrant.

A claim is the assertion that authors would like to prove to their audience. It is, in other words, the main argument.

The grounds of an argument are the evidence and facts that help support the claim.

Finally, the warrant , which is either implied or stated explicitly, is the assumption that links the grounds to the claim.

For example, if you argue that there are dogs nearby:

In this example, in order to assert the claim that a dog is nearby, we provide evidence and specific facts—or the grounds—by acknowledging that we hear barking and howling. Since we know that dogs bark and howl (i.e., since we have a warrant) we can assume that a dog is nearby.

Now, let’s try a more academic approach. Let’s say that you are writing a paper on how more research needs to be done on the way that computer-mediated communication influences online and offline relationships (a paper, in other words, very much like the OWL's APA Sample paper ).

In this case, to assert the claim that additional research needs to be made on how online communication affects relationships, the author shows how the original article needs to account for technological, demographic, and modality limitations in the study. Since we know that when a study lacks a perspective, it would be beneficial to do more research (i.e., we have a warrant), it would be safe to assume that more research should be conducted (i.e. the claim).

The other three elements—backing, qualifier, and rebuttal—are not fundamental to a Toulmin argument, but may be added as necessary. Using these elements wisely can help writers construct full, nuanced arguments.

Backing refers to any additional support of the warrant. In many cases, the warrant is implied, and therefore the backing provides support for the warrant by giving a specific example that justifies the warrant.

The qualifier shows that a claim may not be true in all circumstances. Words like “presumably,” “some,” and “many” help your audience understand that you know there are instances where your claim may not be correct.

The rebuttal is an acknowledgement of another valid view of the situation.

Including a qualifier or a rebuttal in an argument helps build your ethos, or credibility. When you acknowledge that your view isn’t always true or when you provide multiple views of a situation, you build an image of a careful, unbiased thinker, rather than of someone blindly pushing for a single interpretation of the situation.

For example:

We can also add these components to our academic paper example:

Note that, in addition to Stephen Toulmin’s Uses of Argument , students and instructors may find it useful to consult the article “Using Toulmin’s Model of Argumentation” by Joan Karbach for more information.

The Center for Global Studies

Climate change argumentation.

Carmen Vanderhoof, Curriculum and Instruction, College of Education, Penn State

Carmen Vanderhoof is a doctoral candidate in Science Education at Penn State. Her research employs multimodal discourse analysis of elementary students engaged in a collaborative engineering design challenge in order to examine students’ decision-making practices. Prior to resuming graduate studies, she was a secondary science teacher and conducted molecular biology research.

- Subject(s): Earth Science

- Topic: Climate Change and Sustainability

- Grade/Level: 9-12 (can be adapted to grades 6-8)

- Objectives: Students will be able to write a scientific argument using evidence and reasoning to support claims. Students will also be able to reflect on the weaknesses in their own arguments in order to improve their argument and then respond to other arguments.

- Suggested Time Allotment: 4-5 hours (extra time for extension)

This lesson is derived from Dr. Peter Buckland’s sustainability presentation for the Center for Global Studies . Dr. Peter Buckland, a Penn State alumnus, is a postdoctoral fellow for the Sustainability Institute. He has drawn together many resources for teaching about climate change, sustainability, and other environmental issues.

While there are many resources for teaching about climate change and sustainability, it may be tough to figure out where to start. There are massive amounts of data available to the general public and students need help searching for good sources of evidence. Prior to launching into a search, it would be worthwhile figuring out what the students already know about climate change, where they learned it, and how they feel about efforts to reduce our carbon footprint. There are many options for eliciting prior knowledge, including taking online quizzes, whole-class discussion, or drawing concept maps. For this initial step, it is important that students feel comfortable to share, without engaging in disagreements. The main idea is to increase students’ understanding about global warming, rather than focus on the potential controversial nature of this topic.

A major goal of this unit is to engage students in co-constructing evidence-based explanations through individual writing, sharing, re-writing, group discussion, and whole group reflection. The argumentation format presented here contains claims supported by evidence and reasoning (Claims Evidence Reasoning – CER). Argumentation in this sense is different from how the word “argument” is used in everyday language. Argumentation is a collaborative process towards an end goal, rather than a competition to win (Duschl & Osborne, 2002). Scientific argumentation is the process of negotiating and communicating findings through a series of claims supported by evidence from various sources along with a rationale or reasoning linking the claim with the evidence. For students, making the link between claim and evidence can be the most difficult part of the process.

Where does the evidence come from?

Evidence and data are often used synonymously, but there is a difference. Evidence is “the representation of data in a form that undergirds an argument that works to answer the original question” (Hand et al., 2009, p. 129). This explains why even though scientists may use the same data to draw explanations from, the final product may take different forms depending on which parts of the data were used and how. For example, in a court case experts from opposing sides may use the same data to persuade the jury to reach different conclusions. Another way to explain this distinction to students is “the story built from the data that leads to a claim is the evidence” (Hand et al., 2009, p. 129). Evidence can come from many sources – results from controlled experiments, measurements, books, articles, websites, personal observations, etc. It is important to discuss with students the issue of the source’s reliability and accuracy. When using data freely available online, ask yourself: Who conducted the study? Who funded the research? Where was it published or presented?

What is a claim and how do I find it?

A scientific claim is a statement that answers a question or an inference based on information, rather than just personal opinion.

How can I connect the claim(s) with the evidence?

That’s where the justification or reasoning comes in. This portion of the argument explains why the evidence is relevant to the claim or how the evidence supports the claim.

Implementation

Learning context and connecting to state standards.

This interdisciplinary unit can be used in an earth science class or adapted to environmental science, chemistry, or physics. The key to adapting the lesson is guiding students to sources of data that fit the discipline they are studying.

For earth science , students can explain the difference between climate and weather, describe the factors associated with global climate change, and explore a variety of data sources to draw their evidence from. Pennsylvania Academic Standards for earth and space science (secondary): 3.3.12.A1, 3.3.12.A6, 3.3.10.A7.

For environmental science , students can analyze the costs and benefits of pollution control measures. Pennsylvania Academic Standards for Environment and Ecology (secondary): 4.5.12.C.

For chemistry and physics , students can explain the function of greenhouse gases, construct a model of the greenhouse effect, and model energy flow through the atmosphere. Pennsylvania Academic Standards for Physical Sciences (secondary): 3.2.10.B6.

New Generation Science Standards (NGSS) Connections

Human impacts and global climate change are directly addressed in the NGSS. Disciplinary Core Ideas (DCI): HS-ESS3-3, HS-ESS3-4, HS-ESS3-5, HS-ESS3-6.

Lesson 1: Introduction to climate change

- What are greenhouse gases and the greenhouse effect? (sample answer: greenhouse gases like carbon dioxide and methane contribute to overall heating of the atmosphere; these gases trap heat just like the glass in a greenhouse or in a car)

- What is the difference between weather and climate? (sample answer: weather is the daily temperature and precipitation measurements, while climate is a much longer pattern over multiple years)

Drawing of the greenhouse effect – as individuals or in pairs, have students look up the greenhouse effect and draw a diagram to represent it; share out with the class

- Optional: figure out students’ beliefs about global warming using the Yale Six Americas Survey (students answer a series of questions and at the end they are given one of the following categories: alarmed, concerned, cautious, disengaged, doubtful, dismissive).

Lesson 2: Searching for and evaluating evidence

- Compare different data sources and assess their credibility

- Temperature

- Precipitation

- Storm surge

- Ask the students to think about what types of claims they can make about climate change using the data they found (Sample claims: human activity is causing global warming or sea-level rise in the next fifty years will affect coastal cities like Amsterdam, Hong Kong, or New Orleans).

Lesson 3: Writing an argument using evidence

- Claim – an inference or a statement that answers a question

- Evidence – an outside source of information that supports the claim, often drawn from selected data

- Reasoning – the justification/support for the claim; what connects the evidence with the claim

- Extending arguments – have students exchange papers and notice the strengths of the other arguments they are reading (can do multiple cycles of reading); ask students to go back to their original argument and expand it with more evidence and/or more justification for why the evidence supports the claim

- Anticipate Rebuttals – ask students to think and write about any weaknesses in their own argument

Lesson 4: Argumentation discussion

- rebuttal – challenges a component of someone’s argument – for example, a challenge to the evidence used in the original argument

- counterargument – a whole new argument that challenges the original argument

- respect group members and their ideas

- wait for group members to finish their turns before speaking

- be mindful of your own contributions to the discussion (try not to take over the whole discussion so others can contribute too; conversely, if you didn’t already talk, find a way to bring in a new argument, expand on an existing argument, or challenge another argument)

- Debate/discussion – In table groups have students share their arguments and practice rebuttals and counterarguments

- Whole-group reflection – ask students to share key points from their discussion

Lesson 5: Argumentation in action case study

Mumbai, india case study.

Rishi is a thirteen year old boy who attends the Gayak Rafi Nagar Urdu Municipal school in Mumbai. There is a massive landfill called Deonar right across from his school. Every day 4,000 tons of waste are piled on top of the existing garbage spanning 132 hectares (roughly half a square mile). Rishi ventures out to the landfill after school to look for materials that he can later trade for a little bit of extra money to help his family. He feels lucky that he gets to go to school during the day; others are not so lucky. One of his friends, Aamir, had to stop going to school and work full time after his dad got injured. They often meet to chat while they dig through the garbage with sticks. Occasionally, they find books in okay shape, which aren’t worth anything in trade, but to them they are valuable.

One day Rishi was out to the market with his mom and saw the sky darken with a heavy smoke that blocked out the sun. They both hurried home and found out there was a state of emergency and the schools closed for two days. It took many days to put out the fire at Deonar. He heard his dad say that the fire was so bad that it could be seen from space. He wonders what it would be like to see Mumbai from up there. Some days he wishes the government would close down Deonar and clean it up. Other days he wonders what would happen to all the people that depend on it to live if the city shuts down Deonar.

Mumbai is one of the coastal cities that are considered vulnerable with increasing global temperature and sea level rise. The urban poor are most affected by climate change. Their shelter could be wiped out by a tropical storm and rebuilding would be very difficult.

Write a letter to a public official who may be able to influence policy in Mumbai.

What would you recommend they do? Should they close Deonar? What can they do to reduce air pollution in the city and prepare for possible storms? Remember to use evidence in your argument.

If students want to read the articles that inspired the case study direct them to: http://unhabitat.org/urban-themes/climate-change/

http://www.bloomberg.com/slideshow/2012-07-06/top-20-cities-with-billions-at-risk-from-climate-change.html#slide16

http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2015-07-26/smelly-dumps-drive-away-affordable-homes-in-land-starved-mumbai

http://www.cnn.com/2016/02/05/asia/mumbai-giant-garbage-dump-fire/

Resources:

- Lines of Evidence video from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine http://nas-sites.org/americasclimatechoices/videos-multimedia/climate-change-lines-of-evidence-videos/

- Climate Literacy and Energy Awareness Network (CLEAN)

- Climate maps from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

- Sources of data from NASA

- Explore the original source of the Proceedings of the National Academies of Sciences (PNAS) study

Differentiated Instruction

- For visual learners – use diagrams, encourage students to map out their arguments prior to writing them

- For auditory learners – use the lines of evidence video

- For ESL students – provide them with a variety of greenhouse gases diagrams, allow for a more flexible argument format and focus on general meaning-making – ex. using arrows to connect their sources of evidence to claims

- For advanced learners – ask them to search through larger data sets and make comparisons between data from different sources; they can also research environmental policies and why they stalled out in congress

- For learners that need more support – print out excerpts from articles; pinpoint the main ideas to help with the research; help students connect their evidence with their claims; consider allowing students to work in pairs to accomplish the writing task

Argument write-up – check that students’ arguments contain claims supported by evidence and reasoning and that they thought about possible weaknesses in their own arguments.

Case study letter – check that students included evidence in their letter.

References:

Duschl, R. A., & Osborne, J. (2002). Supporting and promoting argumentation discourse in science education.

Hand, B. et al. (2009) Negotiating Science: The Critical Role of Argumentation in Student Inquiry. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

McNeill, K. L., & Krajcik, J. (2012). Claim, evidence and reasoning: Supporting grade 5 – 8 students in constructing scientific explanations. New York, NY: Pearson Allyn & Bacon.

Sawyer, R. K. (Ed.). (2014). The Cambridge handbook of the learning sciences. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

https://www3.epa.gov/climatechange/kids/basics/today/greenhouse-gases.html

http://unhabitat.org/urban-themes/climate-change/

- Writing Center

- Current Students

- Online Only Students

- Faculty & Staff

- Parents & Family

- Alumni & Friends

- Community & Business

- Student Life

- Video Introduction

- Become a Writing Assistant

- All Writers

- Graduate Students

- ELL Students

- Campus and Community

- Testimonials

- Encouraging Writing Center Use

- Incentives and Requirements

- Open Educational Resources

- How We Help

- Get to Know Us

- Conversation Partners Program

- Weekly Workshops

- Workshop Series

- Professors Talk Writing

- Computer Lab

- Starting a Writing Center

- A Note to Instructors

- Annotated Bibliography

- Literature Review

- Research Proposal

- Argument Essay

- Rhetorical Analysis

Argument Analysis

Sometimes, the best way to learn how to write a good argument is to start by analyzing other arguments. When you do this, you get to see what works, what doesn’t, what strategies another author uses, what structures seem to work well and why, and more.

Therefore, even though this section on argument analysis is one of the last lessons in this area, your professor may have you start here before you draft a single word of your own essay.

In the pages that follow, you will learn about analyzing arguments for both content and rhetorical strategies. The content analysis may come a little easier for you, but the rhetorical analysis is extremely important. To become a good writer, we must develop the language of writing and learn how to use that language to talk about the “moves” other writers make.

When we understand the decisions other writers make and why, it helps us make more informed decisions as writers. We can move from being the “accidental” writer, where we might do well but are not sure why, to being a “purposeful” writer, where we have an awareness of the impact our writing has on our audience at all levels.

Thinking About Content

Content analysis of an argument is really just what it seems—looking closely at the content in an argument. When you’re analyzing an argument for content, you’re looking at things like claims, evidence to support those claims, and if that evidence makes sense.

The Toulmin method is a great tool for analyzing the content of an argument. In fact, it was developed as a tool for analyzing the content of an argument. Using the different concepts we learn in the Toulmin model, we are able to examine an argument by thinking about what claim is being made, what evidence is being used to support that claim, the warrants behind that evidence, and more.

When you analyze an argument, there is a good chance your professor will have you review and use the Toulmin information provided in the Excelsior OWL.

However, the lessons you have learned about logical fallacies will also help you analyze the content of an argument. You’ll want to look closely at the logic being presented in the claims and evidence. Does the logic hold up, or do you see logical fallacies? Obviously, if you see fallacies, you should really question the argument.

Thinking Rhetorically

As a part of thinking rhetorically about an argument, your professor may ask you to write a formal or informal rhetorical analysis essay. Rhetorical analysis is about “digging in” and exploring the strategies and writing style of a particular piece. Rhetorical analysis can be tricky because, chances are, you haven’t done a lot of rhetorical analysis in the past.

To add to this trickiness, you can write a rhetorical analysis of any piece of information, not just an essay. You may be asked to write a rhetorical analysis of an ad, an image, or a commercial.

The key is to start now! Rhetorical analysis is going to help you think about strategies other authors have made and how or why these strategies work or don’t work. In turn, your goal is to be more aware of these things in your own writing.

When you analyze a work rhetorically, you are going to explore the following concepts in a piece:

Before you begin to write your research paper, you should think about your audience. Your audience should have an impact on your writing. You should think about audience because, if you want to be effective, you must consider audience needs and expectations. It’s important to remember audience affects both what and how you write.

Most research paper assignments will be written with an academic audience in mind. Writing for an academic audience (your professors and peers) is one of the most difficult writing tasks because college students and faculty make up a very diverse group. It can be difficult for student writers to see outside their own experiences and to think about how other people might react to their messages.

But this kind of rhetorical thinking is necessary to effective writing. Good writers try to see their writing through the eyes of their audience. This, of course, requires a lot of flexibility as a writer, but the rewards for such thinking are great when you have a diverse group of readers interested in and, perhaps, persuaded by your writing.

Rhetorically speaking, purpose is about making decisions as a writer about why you’re writing and what you want your audience to take from your work.

There are three objectives you may have when writing a research paper.

- To inform – When you write a research paper to inform, you’re not making an argument, but you do want to stress the importance of your topic. You might think about your purpose as educating your audience on a particular topic.

- To persuade – When you write a research paper to persuade, your purpose should be to take a stance on your topic. You’ll want to develop a thesis statement that makes a clear assertion about some aspect of your topic.

- To analyze – Although all research papers require some analysis, some research papers make analysis a primary purpose. So, your focus wouldn’t be to inform or persuade, but to analyze your topic. You’ll want to synthesize your research and, ideally, reach new, thoughtful conclusions based on your research.

- TIPS! Here are a few tips when it comes to thinking about purpose.

You must be able to move beyond the idea that you’re writing your research paper only because your professor is making you. While that may be true on some level, you must decide on a purpose based on what topic you’re researching and what you want to say about that topic.

You must decide for yourself, within the requirements of your assignment, why you’re engaging in the research process and writing a paper. Only when you do this will your writing be engaging for your audience.

Your assignment or project instructions affect purpose. If your professor gives you a formal writing assignment sheet for your research paper, it’s especially important to read very carefully through your professor’s expectations. If your professor doesn’t provide a formal assignment sheet, be prepared to ask questions about the purpose of the assignment.

Once you have considered your audience and established your purpose, it’s time to think about voice. Your voice in your writing is essentially how you sound to your audience. Voice is an important part of writing a research paper, but many students never stop to think about voice in their writing. It’s important to remember voice is relative to audience and purpose. The voice you decide to use will have a great impact on your audience.

- Formal – When using a formal, academic or professional voice, you’ll want to be sure to avoid slang and clichés, like “the apple doesn’t fall far from the tree.” You’ll want to avoid conversational tone and even contractions. So, instead of “can’t,” you would want to use “cannot.” You’ll want to think about your academic or professional audience and think about what kind of impression you want your voice to make on that audience.

- Semi-formal – A semi-formal tone is not quite as formal as a formal, academic or professional tone. Although you would certainly want to avoid slang and clichés, you might use contractions, and you might consider a tone that is a little more conversational. Students sometimes make errors in voice, which can have a negative impact on an essay. For example, when writing researched essays for the first time, many students lose their voices entirely to research, and the essay reads more like a list of what other people have said on a particular topic than a real essay. In a research essay, you want to balance your voice with the voices from your sources.

It’s also easy to use a voice that is too informal for college writing, especially when you are just becoming familiar with academia and college expectations.

Ultimately, thinking about your writing rhetorically will help you establish a strong, appropriate voice for your writing.

Appealing to ethos is all about using credibility, either your own as a writer or of your sources, in order to be persuasive. Essentially, ethos is about believability. Will your audience find you believable? What can you do to ensure that they do?

You can establish ethos—or credibility—in two basic ways: you can use or build your own credibility on a topic, or you can use credible sources, which, in turn, builds your credibility as a writer.

Credibility is extremely important in building an argument, so, even if you don’t have a lot of built-in credibility or experience with a topic, it’s important for you to work on your credibility by integrating the credibility of others into your argument.

Aristotle argued that ethos was the most powerful of the modes of persuasion, and while you may disagree, you can’t discount its power. After all, think about the way advertisers use ethos to get us to purchase products. Taylor Swift sells us perfume, and Peyton Manning sells us pizza. But, it’s really their fame and name they are selling.

With the power of ethos in mind, here are some strategies you can use to help build your ethos in your arguments.

If you have specific experience or education related to your issues, mention it in some way.

Appealing to pathos is about appealing to your audience’s emotions. Because people can be easily moved by their emotions, pathos is a powerful mode of persuasion. When you think about appealing to pathos, you should consider all of the potential emotions people experience. While we often see or hear arguments that appeal to sympathy or anger, appealing to pathos is not limited to these specific emotions. You can also use emotions such as humor, joy or even frustration, to note a few, in order to convince your audience.

It’s important, however, to be careful when appealing to pathos, as arguments with an overly-strong focus on emotion are not considered as credible in an academic setting. This means you could, and should, use pathos, but you have to do so carefully. An overly-emotional argument can cause you to lose your credibility as a writer.

You have probably seen many arguments based on an appeal to pathos. In fact, a large number of the commercials you see on television or the internet actually focus primarily on pathos. For example, many car commercials tap into our desire to feel special or important. They suggest that, if you drive a nice car, you will automatically be respected.

With the power of pathos in mind, here are some strategies you can use to carefully build pathos in your arguments.

- Think about the emotions most related to your topic in order to use those emotions effectively. For example, if you’re calling for change in animal abuse laws, you would want to appeal to your audience’s sense of sympathy, possibly by providing examples of animal cruelty. If your argument is focused on environmental issues related to water conservation, you might provide examples of how water shortages affect metropolitan areas in order to appeal to your audience’s fear of a similar occurrence.

- In an effort to appeal to pathos, use examples to illustrate your position. Just be sure the examples you share are credible and can be verified.

- In academic arguments, be sure to balance appeals to pathos with appeals to logos (which will be explored on the next page) in order to maintain your ethos or credibility as a writer.

- When presenting evidenced based on emotion, maintain an even tone of voice. If you sound too emotional, you might lose your audience’s respect.

Logos is about appealing to your audience’s logical side. You have to think about what makes sense to your audience and use that as you build your argument. As writers, we appeal to logos by presenting a line of reasoning in our arguments that is logical and clear. We use evidence, such as statistics and factual information, when we appeal to logos.

In order to develop strong appeals to logos, we have to avoid faulty logic. Faulty logic can be anything from assuming one event caused another to making blanket statements based on little evidence. Logical fallacies should always be avoided. We will explore logical fallacies in another section.

Appeals to logos are an important part of academic writing, but you will see them in commercials as well. Although they more commonly use pathos and ethos, advertisers will sometimes use logos to sell products. For example, commercials based on saving consumers money, such as car commercials that focus on miles-per-gallon, are appealing to the consumers’ sense of logos.

As you work to build logos in your arguments, here are some strategies to keep in mind.

- Both experience and source material can provide you with evidence to appeal to logos. While outside sources will provide you with excellent evidence in an argumentative essay, in some situations, you can share personal experiences and observations. Just make sure they are appropriate to the situation and you present them in a clear and logical manner.

- Remember to think about your audience as you appeal to logos. Just because something makes sense in your mind, doesn’t mean it will make the same kind of sense to your audience. You need to try to see things from your audience’s perspective. Having others read your writing, especially those who might disagree with your position, is helpful.

- Be sure to maintain clear lines of reasoning throughout your argument. One error in logic can negatively impact your entire position. When you present faulty logic, you lose credibility.

- When presenting an argument based on logos, it is important to avoid emotional overtones and maintain an even tone of voice. Remember, it’s not just a matter of the type of evidence you are presenting; how you present this evidence is important as well.

You will be thinking about the decisions an author has made along these lines and thinking about whether these decisions are effective or ineffective.

The following page provides a sample rhetorical analysis with some notes to help you better understand your goals when writing a formal rhetorical analysis.

This content was created by Excelsior Online Writing Lab (OWL) and is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-4.0 International License . You are free to use, adapt, and/or share this material as long as you properly attribute. Please keep this information on materials you use, adapt, and/or share for attribution purposes.

Contact Info

Kennesaw Campus 1000 Chastain Road Kennesaw, GA 30144

Marietta Campus 1100 South Marietta Pkwy Marietta, GA 30060

Campus Maps

Phone 470-KSU-INFO (470-578-4636)

kennesaw.edu/info

Media Resources

Resources For

Related Links

- Financial Aid

- Degrees, Majors & Programs

- Job Opportunities

- Campus Security

- Global Education

- Sustainability

- Accessibility

470-KSU-INFO (470-578-4636)

© 2024 Kennesaw State University. All Rights Reserved.

- Privacy Statement

- Accreditation

- Emergency Information

- Report a Concern

- Open Records

- Human Trafficking Notice

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

This essay will look at the issue of global warming using the Toulmin model (Toulmin, 1; Fullerton.edu, 1). As such, the following sections will be discussed in the essay in line with the model: Claim: Looking at the issue of global warming, it is clear that there are many causes culminating into the pollution of the environment, and the ...

9. Toulmin Argument Model. by Liza Long, Amy Minervini, and Joel Gladd. Stephen Edelston Toulmin (born March 25, 1922) was a British philosopher, author, and educator. Toulmin devoted his works to analyzing moral reasoning. He sought to develop practical ways to evaluate ethical arguments effectively. The Toulmin Model of Argumentation, a ...

Research aims to determine the profile of Toulmin's Scientific Argument on students' and Technological Utilities In Global Warning Topic. This research is a quantitative descriptive study using ...

What is the Toulmin Method? Developed by philosopher Stephen E. Toulmin, the Toulmin method is a style of argumentation that breaks arguments down into six component parts: claim, grounds, warrant, qualifier, rebuttal, and backing. In Toulmin's method, every argument begins with three fundamental parts: the claim, the grounds, and the warrant.

Bart Verheij. The only book-length comprehensive study of Stephen Toulmin's influential model for the layout of arguments. New essays on argument analysis and evaluation by 27 scholars from 10 countries in the fields of artificial intelligence, philosophy, psychology and speech communication. Novel contributions to the theory of non-formal ...

Ask the students to think about what types of claims they can make about climate change using the data they found (Sample claims: human activity is causing global warming or sea-level rise in the next fifty years will affect coastal cities like Amsterdam, Hong Kong, or New Orleans). Lesson 3: Writing an argument using evidence

Toulmin Argument Model Stephen Toulmin (The Uses of Argument, 1958), a British philosopher, is credited for developing a system of making practical arguments. His argument system is based on justifying claims, and it involves analyzing your own argument from all sides to make it stronger. A Toulmin argument consists of the following components:

Argument Analysis. Sometimes, the best way to learn how to write a good argument is to start by analyzing other arguments. When you do this, you get to see what works, what doesn't, what strategies another author uses, what structures seem to work well and why, and more. Therefore, even though this section on argument analysis is one of the ...

ethod of analyzing and building arguments. It can be especially helpful. you are suffering from writer's block. This model is most effective when t. ere are no clear answers to your argument. It consists of six parts: three fundamental elements are the claim, grounds, and warrant; then, the optional element. alifier, and rebuttal. T.

Limitations of Toulmin. Somewhat static view of an argument. Focuses on the argument maker, not the target or respondent. Real-life arguments aren't always neat or clear. The Toulmin model is an analytical tool, so it's more useful for dissecting arguments later than in the "heat" of an argument.