- Privacy Policy

Home » Qualitative Research – Methods, Analysis Types and Guide

Qualitative Research – Methods, Analysis Types and Guide

Table of Contents

Qualitative Research

Qualitative research is a type of research methodology that focuses on exploring and understanding people’s beliefs, attitudes, behaviors, and experiences through the collection and analysis of non-numerical data. It seeks to answer research questions through the examination of subjective data, such as interviews, focus groups, observations, and textual analysis.

Qualitative research aims to uncover the meaning and significance of social phenomena, and it typically involves a more flexible and iterative approach to data collection and analysis compared to quantitative research. Qualitative research is often used in fields such as sociology, anthropology, psychology, and education.

Qualitative Research Methods

Qualitative Research Methods are as follows:

One-to-One Interview

This method involves conducting an interview with a single participant to gain a detailed understanding of their experiences, attitudes, and beliefs. One-to-one interviews can be conducted in-person, over the phone, or through video conferencing. The interviewer typically uses open-ended questions to encourage the participant to share their thoughts and feelings. One-to-one interviews are useful for gaining detailed insights into individual experiences.

Focus Groups

This method involves bringing together a group of people to discuss a specific topic in a structured setting. The focus group is led by a moderator who guides the discussion and encourages participants to share their thoughts and opinions. Focus groups are useful for generating ideas and insights, exploring social norms and attitudes, and understanding group dynamics.

Ethnographic Studies

This method involves immersing oneself in a culture or community to gain a deep understanding of its norms, beliefs, and practices. Ethnographic studies typically involve long-term fieldwork and observation, as well as interviews and document analysis. Ethnographic studies are useful for understanding the cultural context of social phenomena and for gaining a holistic understanding of complex social processes.

Text Analysis

This method involves analyzing written or spoken language to identify patterns and themes. Text analysis can be quantitative or qualitative. Qualitative text analysis involves close reading and interpretation of texts to identify recurring themes, concepts, and patterns. Text analysis is useful for understanding media messages, public discourse, and cultural trends.

This method involves an in-depth examination of a single person, group, or event to gain an understanding of complex phenomena. Case studies typically involve a combination of data collection methods, such as interviews, observations, and document analysis, to provide a comprehensive understanding of the case. Case studies are useful for exploring unique or rare cases, and for generating hypotheses for further research.

Process of Observation

This method involves systematically observing and recording behaviors and interactions in natural settings. The observer may take notes, use audio or video recordings, or use other methods to document what they see. Process of observation is useful for understanding social interactions, cultural practices, and the context in which behaviors occur.

Record Keeping

This method involves keeping detailed records of observations, interviews, and other data collected during the research process. Record keeping is essential for ensuring the accuracy and reliability of the data, and for providing a basis for analysis and interpretation.

This method involves collecting data from a large sample of participants through a structured questionnaire. Surveys can be conducted in person, over the phone, through mail, or online. Surveys are useful for collecting data on attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors, and for identifying patterns and trends in a population.

Qualitative data analysis is a process of turning unstructured data into meaningful insights. It involves extracting and organizing information from sources like interviews, focus groups, and surveys. The goal is to understand people’s attitudes, behaviors, and motivations

Qualitative Research Analysis Methods

Qualitative Research analysis methods involve a systematic approach to interpreting and making sense of the data collected in qualitative research. Here are some common qualitative data analysis methods:

Thematic Analysis

This method involves identifying patterns or themes in the data that are relevant to the research question. The researcher reviews the data, identifies keywords or phrases, and groups them into categories or themes. Thematic analysis is useful for identifying patterns across multiple data sources and for generating new insights into the research topic.

Content Analysis

This method involves analyzing the content of written or spoken language to identify key themes or concepts. Content analysis can be quantitative or qualitative. Qualitative content analysis involves close reading and interpretation of texts to identify recurring themes, concepts, and patterns. Content analysis is useful for identifying patterns in media messages, public discourse, and cultural trends.

Discourse Analysis

This method involves analyzing language to understand how it constructs meaning and shapes social interactions. Discourse analysis can involve a variety of methods, such as conversation analysis, critical discourse analysis, and narrative analysis. Discourse analysis is useful for understanding how language shapes social interactions, cultural norms, and power relationships.

Grounded Theory Analysis

This method involves developing a theory or explanation based on the data collected. Grounded theory analysis starts with the data and uses an iterative process of coding and analysis to identify patterns and themes in the data. The theory or explanation that emerges is grounded in the data, rather than preconceived hypotheses. Grounded theory analysis is useful for understanding complex social phenomena and for generating new theoretical insights.

Narrative Analysis

This method involves analyzing the stories or narratives that participants share to gain insights into their experiences, attitudes, and beliefs. Narrative analysis can involve a variety of methods, such as structural analysis, thematic analysis, and discourse analysis. Narrative analysis is useful for understanding how individuals construct their identities, make sense of their experiences, and communicate their values and beliefs.

Phenomenological Analysis

This method involves analyzing how individuals make sense of their experiences and the meanings they attach to them. Phenomenological analysis typically involves in-depth interviews with participants to explore their experiences in detail. Phenomenological analysis is useful for understanding subjective experiences and for developing a rich understanding of human consciousness.

Comparative Analysis

This method involves comparing and contrasting data across different cases or groups to identify similarities and differences. Comparative analysis can be used to identify patterns or themes that are common across multiple cases, as well as to identify unique or distinctive features of individual cases. Comparative analysis is useful for understanding how social phenomena vary across different contexts and groups.

Applications of Qualitative Research

Qualitative research has many applications across different fields and industries. Here are some examples of how qualitative research is used:

- Market Research: Qualitative research is often used in market research to understand consumer attitudes, behaviors, and preferences. Researchers conduct focus groups and one-on-one interviews with consumers to gather insights into their experiences and perceptions of products and services.

- Health Care: Qualitative research is used in health care to explore patient experiences and perspectives on health and illness. Researchers conduct in-depth interviews with patients and their families to gather information on their experiences with different health care providers and treatments.

- Education: Qualitative research is used in education to understand student experiences and to develop effective teaching strategies. Researchers conduct classroom observations and interviews with students and teachers to gather insights into classroom dynamics and instructional practices.

- Social Work : Qualitative research is used in social work to explore social problems and to develop interventions to address them. Researchers conduct in-depth interviews with individuals and families to understand their experiences with poverty, discrimination, and other social problems.

- Anthropology : Qualitative research is used in anthropology to understand different cultures and societies. Researchers conduct ethnographic studies and observe and interview members of different cultural groups to gain insights into their beliefs, practices, and social structures.

- Psychology : Qualitative research is used in psychology to understand human behavior and mental processes. Researchers conduct in-depth interviews with individuals to explore their thoughts, feelings, and experiences.

- Public Policy : Qualitative research is used in public policy to explore public attitudes and to inform policy decisions. Researchers conduct focus groups and one-on-one interviews with members of the public to gather insights into their perspectives on different policy issues.

How to Conduct Qualitative Research

Here are some general steps for conducting qualitative research:

- Identify your research question: Qualitative research starts with a research question or set of questions that you want to explore. This question should be focused and specific, but also broad enough to allow for exploration and discovery.

- Select your research design: There are different types of qualitative research designs, including ethnography, case study, grounded theory, and phenomenology. You should select a design that aligns with your research question and that will allow you to gather the data you need to answer your research question.

- Recruit participants: Once you have your research question and design, you need to recruit participants. The number of participants you need will depend on your research design and the scope of your research. You can recruit participants through advertisements, social media, or through personal networks.

- Collect data: There are different methods for collecting qualitative data, including interviews, focus groups, observation, and document analysis. You should select the method or methods that align with your research design and that will allow you to gather the data you need to answer your research question.

- Analyze data: Once you have collected your data, you need to analyze it. This involves reviewing your data, identifying patterns and themes, and developing codes to organize your data. You can use different software programs to help you analyze your data, or you can do it manually.

- Interpret data: Once you have analyzed your data, you need to interpret it. This involves making sense of the patterns and themes you have identified, and developing insights and conclusions that answer your research question. You should be guided by your research question and use your data to support your conclusions.

- Communicate results: Once you have interpreted your data, you need to communicate your results. This can be done through academic papers, presentations, or reports. You should be clear and concise in your communication, and use examples and quotes from your data to support your findings.

Examples of Qualitative Research

Here are some real-time examples of qualitative research:

- Customer Feedback: A company may conduct qualitative research to understand the feedback and experiences of its customers. This may involve conducting focus groups or one-on-one interviews with customers to gather insights into their attitudes, behaviors, and preferences.

- Healthcare : A healthcare provider may conduct qualitative research to explore patient experiences and perspectives on health and illness. This may involve conducting in-depth interviews with patients and their families to gather information on their experiences with different health care providers and treatments.

- Education : An educational institution may conduct qualitative research to understand student experiences and to develop effective teaching strategies. This may involve conducting classroom observations and interviews with students and teachers to gather insights into classroom dynamics and instructional practices.

- Social Work: A social worker may conduct qualitative research to explore social problems and to develop interventions to address them. This may involve conducting in-depth interviews with individuals and families to understand their experiences with poverty, discrimination, and other social problems.

- Anthropology : An anthropologist may conduct qualitative research to understand different cultures and societies. This may involve conducting ethnographic studies and observing and interviewing members of different cultural groups to gain insights into their beliefs, practices, and social structures.

- Psychology : A psychologist may conduct qualitative research to understand human behavior and mental processes. This may involve conducting in-depth interviews with individuals to explore their thoughts, feelings, and experiences.

- Public Policy: A government agency or non-profit organization may conduct qualitative research to explore public attitudes and to inform policy decisions. This may involve conducting focus groups and one-on-one interviews with members of the public to gather insights into their perspectives on different policy issues.

Purpose of Qualitative Research

The purpose of qualitative research is to explore and understand the subjective experiences, behaviors, and perspectives of individuals or groups in a particular context. Unlike quantitative research, which focuses on numerical data and statistical analysis, qualitative research aims to provide in-depth, descriptive information that can help researchers develop insights and theories about complex social phenomena.

Qualitative research can serve multiple purposes, including:

- Exploring new or emerging phenomena : Qualitative research can be useful for exploring new or emerging phenomena, such as new technologies or social trends. This type of research can help researchers develop a deeper understanding of these phenomena and identify potential areas for further study.

- Understanding complex social phenomena : Qualitative research can be useful for exploring complex social phenomena, such as cultural beliefs, social norms, or political processes. This type of research can help researchers develop a more nuanced understanding of these phenomena and identify factors that may influence them.

- Generating new theories or hypotheses: Qualitative research can be useful for generating new theories or hypotheses about social phenomena. By gathering rich, detailed data about individuals’ experiences and perspectives, researchers can develop insights that may challenge existing theories or lead to new lines of inquiry.

- Providing context for quantitative data: Qualitative research can be useful for providing context for quantitative data. By gathering qualitative data alongside quantitative data, researchers can develop a more complete understanding of complex social phenomena and identify potential explanations for quantitative findings.

When to use Qualitative Research

Here are some situations where qualitative research may be appropriate:

- Exploring a new area: If little is known about a particular topic, qualitative research can help to identify key issues, generate hypotheses, and develop new theories.

- Understanding complex phenomena: Qualitative research can be used to investigate complex social, cultural, or organizational phenomena that are difficult to measure quantitatively.

- Investigating subjective experiences: Qualitative research is particularly useful for investigating the subjective experiences of individuals or groups, such as their attitudes, beliefs, values, or emotions.

- Conducting formative research: Qualitative research can be used in the early stages of a research project to develop research questions, identify potential research participants, and refine research methods.

- Evaluating interventions or programs: Qualitative research can be used to evaluate the effectiveness of interventions or programs by collecting data on participants’ experiences, attitudes, and behaviors.

Characteristics of Qualitative Research

Qualitative research is characterized by several key features, including:

- Focus on subjective experience: Qualitative research is concerned with understanding the subjective experiences, beliefs, and perspectives of individuals or groups in a particular context. Researchers aim to explore the meanings that people attach to their experiences and to understand the social and cultural factors that shape these meanings.

- Use of open-ended questions: Qualitative research relies on open-ended questions that allow participants to provide detailed, in-depth responses. Researchers seek to elicit rich, descriptive data that can provide insights into participants’ experiences and perspectives.

- Sampling-based on purpose and diversity: Qualitative research often involves purposive sampling, in which participants are selected based on specific criteria related to the research question. Researchers may also seek to include participants with diverse experiences and perspectives to capture a range of viewpoints.

- Data collection through multiple methods: Qualitative research typically involves the use of multiple data collection methods, such as in-depth interviews, focus groups, and observation. This allows researchers to gather rich, detailed data from multiple sources, which can provide a more complete picture of participants’ experiences and perspectives.

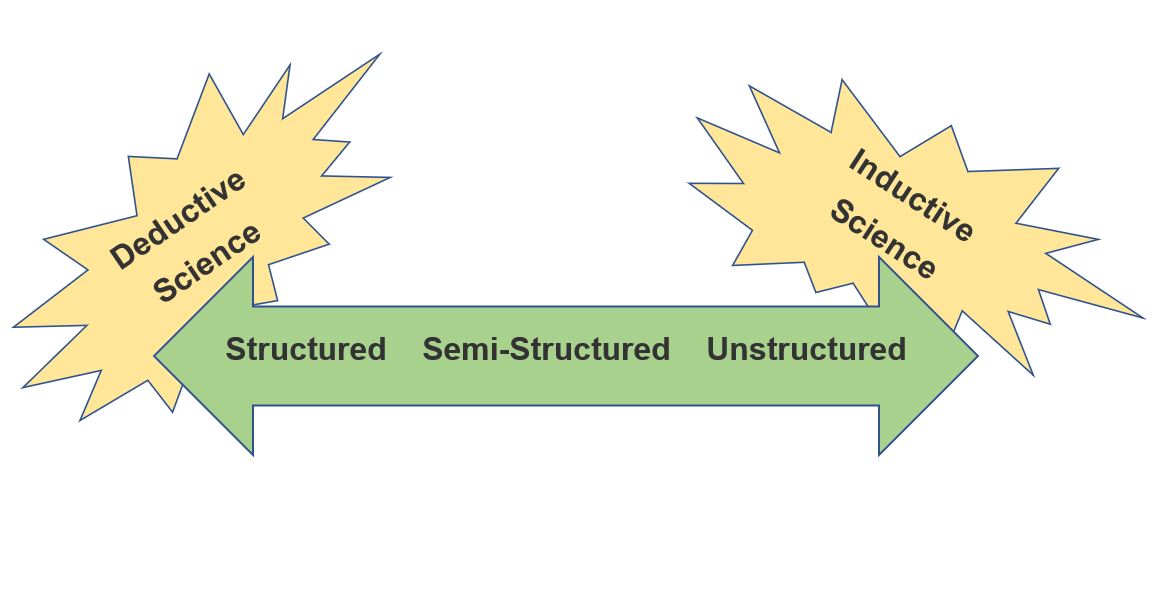

- Inductive data analysis: Qualitative research relies on inductive data analysis, in which researchers develop theories and insights based on the data rather than testing pre-existing hypotheses. Researchers use coding and thematic analysis to identify patterns and themes in the data and to develop theories and explanations based on these patterns.

- Emphasis on researcher reflexivity: Qualitative research recognizes the importance of the researcher’s role in shaping the research process and outcomes. Researchers are encouraged to reflect on their own biases and assumptions and to be transparent about their role in the research process.

Advantages of Qualitative Research

Qualitative research offers several advantages over other research methods, including:

- Depth and detail: Qualitative research allows researchers to gather rich, detailed data that provides a deeper understanding of complex social phenomena. Through in-depth interviews, focus groups, and observation, researchers can gather detailed information about participants’ experiences and perspectives that may be missed by other research methods.

- Flexibility : Qualitative research is a flexible approach that allows researchers to adapt their methods to the research question and context. Researchers can adjust their research methods in real-time to gather more information or explore unexpected findings.

- Contextual understanding: Qualitative research is well-suited to exploring the social and cultural context in which individuals or groups are situated. Researchers can gather information about cultural norms, social structures, and historical events that may influence participants’ experiences and perspectives.

- Participant perspective : Qualitative research prioritizes the perspective of participants, allowing researchers to explore subjective experiences and understand the meanings that participants attach to their experiences.

- Theory development: Qualitative research can contribute to the development of new theories and insights about complex social phenomena. By gathering rich, detailed data and using inductive data analysis, researchers can develop new theories and explanations that may challenge existing understandings.

- Validity : Qualitative research can offer high validity by using multiple data collection methods, purposive and diverse sampling, and researcher reflexivity. This can help ensure that findings are credible and trustworthy.

Limitations of Qualitative Research

Qualitative research also has some limitations, including:

- Subjectivity : Qualitative research relies on the subjective interpretation of researchers, which can introduce bias into the research process. The researcher’s perspective, beliefs, and experiences can influence the way data is collected, analyzed, and interpreted.

- Limited generalizability: Qualitative research typically involves small, purposive samples that may not be representative of larger populations. This limits the generalizability of findings to other contexts or populations.

- Time-consuming: Qualitative research can be a time-consuming process, requiring significant resources for data collection, analysis, and interpretation.

- Resource-intensive: Qualitative research may require more resources than other research methods, including specialized training for researchers, specialized software for data analysis, and transcription services.

- Limited reliability: Qualitative research may be less reliable than quantitative research, as it relies on the subjective interpretation of researchers. This can make it difficult to replicate findings or compare results across different studies.

- Ethics and confidentiality: Qualitative research involves collecting sensitive information from participants, which raises ethical concerns about confidentiality and informed consent. Researchers must take care to protect the privacy and confidentiality of participants and obtain informed consent.

Also see Research Methods

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Correlational Research – Methods, Types and...

Research Methods – Types, Examples and Guide

Mixed Methods Research – Types & Analysis

Experimental Design – Types, Methods, Guide

Textual Analysis – Types, Examples and Guide

Explanatory Research – Types, Methods, Guide

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

- QuestionPro

- Solutions Industries Gaming Automotive Sports and events Education Government Travel & Hospitality Financial Services Healthcare Cannabis Technology Use Case AskWhy Communities Audience Contactless surveys Mobile LivePolls Member Experience GDPR Positive People Science 360 Feedback Surveys

- Resources Blog eBooks Survey Templates Case Studies Training Help center

Home Market Research

Qualitative Data Collection Methods: What it is + Process

If you want to go beyond numbers and really understand how people think and feel, qualitative data collection methods are the way to do it. These methods focus on gathering in-depth insights into the “why” and “how” behind people’s actions and experiences. Instead of just relying on statistics, you get detailed, personal feedback that helps you understand your audience on a deeper level.

Several methods are used to collect qualitative data, including interviews, surveys, focus groups, and observations. Understanding the various methods used for gathering qualitative data is essential for successful qualitative research.

In this blog, we will discuss qualitative data, its processes, and its collection methods.

What is Qualitative Data?

Qualitative data is information that describes and explains something. It can be seen, observed, and written down.

This data type is non-numerical in nature. This type of data is collected through methods of observations, one-to-one interviews, conducting focus groups, and similar methods.

Qualitative data in statistics is also known as categorical data – data that can be arranged categorically based on the attributes and properties of a thing or a phenomenon.

It’s pretty easy to understand the difference between qualitative and quantitative data. Qualitative data does not include numbers in its definition of traits, whereas quantitative research data is all about numbers.

- The cake is orange, blue, and black in color (qualitative).

- Females have brown, black, blonde, and red hair (qualitative).

What Are Qualitative Data Collection Methods?

Qualitative data collection methods are ways to gather information that helps you understand people’s thoughts, feelings, and experiences. Unlike numbers and statistics, this type of data is more about understanding the “why” and “how” behind something. It’s like having a conversation to get deeper insights into what people think or feel.

The data collected through qualitative methods are often subjective, open-ended, and unstructured and can provide a rich understanding of complex social phenomena.

In statistical analysis , the diffe rence between categorical data and numerical data is essential, as categorical data involves distinct categories or labels, while numerical data consists of measurable quantities.

What is the Need For Qualitative Data Collection?

Qualitative research is a type of study carried out with a qualitative approach to understand the exploratory reasons and to assay how and why a specific program or phenomenon operates in the way it is working. A researcher can access numerous qualitative data collection methods that he/she feels are relevant.

Qualitative data collection methods serve the primary purpose of collecting textual data for research and analysis , like thematic analysis . The collected research data is used to examine:

- Knowledge around a specific issue or a program, experience of people.

- Meaning and relationships.

- Social norms and contextual or cultural practices demean people or impact a cause.

The qualitative data is textual or non-numerical. It covers mostly the images, videos, texts, and written or spoken words by the people. You can opt for any digital data collection methods , like structured or semi-structured surveys, or settle for the traditional approach comprising individual interviews, group discussions, etc.

Are you curious to know about Best Data Collection Tools? QuestionPro recently published a blog about it. Explore it to learn more.

Effective Qualitative Data Collection Methods

Data at hand leads to a smooth process ensuring all the decisions made are for the business’s betterment. You will be able to make informed decisions only if you have relevant data.

Well! With quality data, you will improve the quality of decision-making. You will also improve the quality of the results you expect from any effort.

Qualitative data collection methods are exploratory. Those are usually more focused on gaining insights and understanding the underlying reasons by digging deeper.

Although quantitative data cannot be quantified, measuring it or analyzing qualitative data might become an issue. Due to the lack of measurability, collection methods of qualitative data are primarily unstructured or structured in rare cases – that too to some extent.

Let’s explore the most common methods used for the collection of qualitative data:

Individual interview

It is one of the most trusted, widely used, and familiar qualitative data collection methods primarily because of its approach. An individual or face-to-face interview is a direct conversation between two people with a specific structure and purpose.

The interview questionnaire is designed to elicit the interviewee’s knowledge or perspective related to a topic, program, or issue.

At times, depending on the interviewer’s approach, the conversation can be unstructured or informal but focused on understanding the individual’s beliefs, values, understandings, feelings, experiences, and perspectives on an issue.

More often, the interviewer chooses to ask open-ended questions in individual interviews. If the interviewee selects answers from a set of given options, it becomes a structured, fixed response or a biased discussion.

The individual interview is an ideal qualitative data collection method. Particularly when the researchers want highly personalized information from the participants. The individual interview is a notable method if the interviewer decides to probe further and ask follow-up questions to gain more insights.

Qualitative surveys

To develop an informed hypothesis, many researchers use qualitative research surveys for data collection or to collect a piece of detailed information about a product or an issue. If you want to create questionnaires for collecting textual or qualitative data, then ask more open-ended questions .

To answer such qualitative research questions , the respondent has to write his/her opinion or perspective concerning a specific topic or issue. Unlike other collection methods, online surveys have a wider reach. People can provide you with quality data that is highly credible and valuable.

Paper surveys

Online surveys, focus group discussions.

Focus group discussions can also be considered a type of interview, but it is conducted in a group discussion setting. Usually, the focus group consists of 8 – 10 people (the size may vary depending on the researcher’s requirement). The researchers ensure appropriate space is given to the participants to discuss a topic or issue in a context. The participants are allowed to either agree or disagree with each other’s comments.

With a focused group discussion, researchers know how a particular group of participants perceives the topic. Researchers analyze what participants think of an issue, the range of opinions expressed, and the ideas discussed. The data is collected by noting down the variations or inconsistencies (if any exist) in the participants, especially in terms of belief, experiences, and practice.

The participants of focused group discussions are selected based on the topic or issues for which the researcher wants actionable insights. For example, if the research is about the recovery of college students from drug addiction. The participants have to be college students studying and recovering from drug addiction.

Other parameters such as age, qualification, financial background, social presence, and demographics are also considered, but not primarily, as the group needs diverse participants. Frequently, the qualitative data collected through focused group discussion is more descriptive and highly detailed.

Record keeping

This method uses reliable documents and other sources of information that already exist as the data source. This information can help with the new study. It’s a lot like going to the library. There, you can look through books and other sources to find information that can be used in your research.

Case studies

In this method, data is collected by looking at case studies in detail. This method’s flexibility is shown by the fact that it can be used to analyze both simple and complicated topics. This method’s strength is how well it draws conclusions from a mix of one or more qualitative data collection methods.

Observations

Observation is one of the traditional methods of qualitative data collection. It is used by researchers to gather descriptive analysis data by observing people and their behavior at events or in their natural settings. In this method, the researcher fully involves themselves in observing people and taking part in the activities while making notes.

There are two main types of observation:

- Covert: In this method, the observer is concealed without letting anyone know that they are being observed. For example, a researcher studying the rituals of a wedding in nomadic tribes must join them as a guest and quietly see everything.

- Overt: In this method, everyone is aware that they are being watched. For example, A researcher or an observer wants to study the wedding rituals of a nomadic tribe. To proceed with the research, the observer or researcher can reveal why he is attending the marriage and even use a video camera to shoot everything around him.

Observation is a useful method of qualitative data collection, especially when you want to study the ongoing process, situation, or reactions on a specific issue related to the people being observed.

When you want to understand people’s behavior or their way of interaction in a particular community or demographic, you can rely on the observation data. Remember, if you fail to get quality data through surveys, qualitative interviews , or group discussions, rely on observation.

It is the best and most trusted collection method of qualitative data to generate qualitative data as it requires equal to no effort from the participants.

Qualitative Data Analysis Process

You invested time and money acquiring your data, so analyze it. It’s necessary to avoid being in the dark after all your hard work. Qualitative data analysis starts with knowing its two basic techniques, but there are no rules.

- Deductive Approach: The deductive data analysis uses a researcher-defined structure to analyze qualitative data. This method is quick and easy when a researcher knows what the sample population will say.

- Inductive Approach: The inductive technique has no structure or framework. When a researcher knows little about the event, an inductive approach is applied.

Whether you want to analyze qualitative data from a one-on-one interview or a survey, these simple steps will ensure a smooth qualitative data analysis.

Step 1: Collect your Data

After collecting all the data, it is mostly unstructured and sometimes unclear. Arranging your data is the first stage in qualitative data analysis. So, researchers must transcribe data before analyzing it.

Step 2: Organize all your Data

After transforming and arranging your data, the next step is to organize it. One of the best ways to organize the data is to think back to your research goals and then organize the data based on the research questions you asked.

Step 3: Set a Code to the Data Collected

Setting up appropriate codes for the collected data gets you one step closer. Coding is one of the most effective methods for compressing a massive amount of data. It allows you to derive theories from relevant research findings.

Step 4: Validate your Data

Qualitative data analysis success requires data validation. Data validation should be done throughout the research process, not just once. There are two sides to validating data:

- The accuracy of your research design or methods.

- Reliability—how well the approaches deliver accurate data.

Step 5: Concluding the Analysis Process

Finally, conclude your data in a presentable report. The report should describe your research methods, their pros and cons, and research limitations. Your report should include findings, inferences, and future research.

QuestionPro is an excellent online survey software that offers a variety of qualitative data analysis tools to help businesses and researchers in making sense of their data. Users can use many different qualitative analysis methods to learn more about their data.

Users of QuestionPro can see their data in different charts and graphs, which makes it easier to spot patterns and trends. It can help researchers and businesses learn more about their target audience, which can lead to better decisions and better results.

Choosing the right software can be tough. Whether you’re a researcher, business leader, or marketer, check out the top 10 qualitative data analysis software for analyzing qualitative data.

Advantages of Qualitative Data Collection

Qualitative data collection has several advantages, including:

- In-depth understanding: It provides in-depth information about attitudes and behaviors, leading to a deeper understanding of the research.

- Flexibility: The methods allow researchers to modify questions or change direction if new information emerges.

- Contextualization: Qualitative research data is in context, which helps to provide a deep understanding of the experiences and perspectives of individuals.

- Rich data: It often produces rich, detailed, and nuanced information that cannot be captured through numerical data.

- Engagement: The methods, such as interviews and focus groups, involve active meetings with participants, leading to a deeper understanding.

- Multiple perspectives: This can provide various views and a rich array of voices, adding depth and complexity.

- Realistic setting: It often occurs in realistic settings, providing more authentic experiences and behaviors.

Qualitative research methods are best for collecting qualitative data and identifying the behavior and patterns governing social conditions, issues, or topics. It spans a step ahead of quantitative data as it fails to explain the reasons and rationale behind a phenomenon, but qualitative data quickly does.

Qualitative research is one of the best tools to identify behaviors and patterns governing social conditions. It goes a step beyond quantitative data by providing the reasons and rationale behind a phenomenon that cannot be explored quantitatively.

With QuestionPro, you can use it for qualitative data collection through various methods. Using Our robust suite correctly, you can enhance the quality and integrity of the collected data.

LEARN MORE FREE TRIAL

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Qualitative methods provide deeper insights than numbers alone. They help you explore complex topics, understand motivations, and gather rich feedback. These methods are especially useful when you need to understand the underlying reasons for people’s actions or preferences.

Choosing the right method depends on your research goals. If you want detailed individual insights, interviews work well. For group dynamics, focus groups are better. If you want to observe natural behavior, observation is ideal. Consider what kind of data will give you the most valuable insights.

Some challenges include managing large amounts of data, ensuring participant honesty, and avoiding researcher bias during analysis. Qualitative research also requires more time and effort compared to quantitative methods, as it involves in-depth interviews and analysis.

MORE LIKE THIS

Maximize Employee Feedback with QuestionPro Workforce’s Slack Integration

Nov 6, 2024

2024 Presidential Election Polls: Harris vs. Trump

Nov 5, 2024

Your First Question Should Be Anything But, “Is The Car Okay?” — Tuesday CX Thoughts

QuestionPro vs. Qualtrics: Who Offers the Best 360-Degree Feedback Platform for Your Needs?

Nov 4, 2024

Other categories

- Academic Research

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assessments

- Brand Awareness

- Case Studies

- Communities

- Consumer Insights

- Customer effort score

- Customer Engagement

- Customer Experience

- Customer Loyalty

- Customer Research

- Customer Satisfaction

- Employee Benefits

- Employee Engagement

- Employee Retention

- Friday Five

- General Data Protection Regulation

- Insights Hub

- Life@QuestionPro

- Market Research

- Mobile diaries

- Mobile Surveys

- New Features

- Online Communities

- Question Types

- Questionnaire

- QuestionPro Products

- Release Notes

- Research Tools and Apps

- Revenue at Risk

- Survey Templates

- Training Tips

- Tuesday CX Thoughts (TCXT)

- Uncategorized

- What’s Coming Up

- Workforce Intelligence

UpMetrics Blog

Expert insights, trends, and best practices around impact measurement and leveraging actionable data to drive meaningful change.

8 Essential Qualitative Data Collection Methods

Qualitative data methods allow you to dive deep into the mindset of your audience to discover areas for growth, development, and improvement.

British mathematician and marketing mastermind Clive Humby once famously stated that “Data is the new oil.” He has a point. Without data, nonprofit organizations are left second-guessing what their clients and supporters think, how their brand compares to others in the market, whether their messaging is on-point, how their campaigns are performing, where improvements can be made, and how overall results can be optimized.

There are two primary data collection methodologies: qualitative data collection and quantitative data collection. At UpMetrics, we believe that just relying on quantitative, static data is no longer an option to drive effective impact. In this guide, we’ll focus on qualitative data collection methods and how they can help you gather, analyze, and collate information that can help drive your organization forward.

What is Qualitative Data?

Data collection in qualitative research focuses on gathering contextual information. Unlike quantitative data, which focuses primarily on numbers to establish ‘how many’ or ‘how much,’ qualitative data collection tools allow you to assess the ‘why’s’ and ‘how’s’ behind those statistics. This is vital for nonprofits as it enables organizations to determine:

- Existing knowledge surrounding a particular issue.

- How social norms and cultural practices impact a cause.

- What kind of experiences and interactions people have with your brand.

- Trends in the way people change their opinions.

- Whether meaningful relationships are being established between all parties.

In short, qualitative data collection methods collect perceptual and descriptive information that helps you understand the reasoning and motivation behind particular reactions and behaviors. For that reason, qualitative data methods are usually non-numerical and center around spoken and written words rather than data extrapolated from a spreadsheet or report.

Qualitative vs. Quantitative Data

Quantitative and qualitative data represent both sides of the same coin. There will always be some degree of debate over the importance of quantitative vs. qualitative research, data, and collection. However, successful organizations should strive to achieve a balance between the two.

Organizations can track their performance by collecting quantitative data based on metrics including dollars raised, membership growth, number of people served, overhead costs, etc. This is all essential information to have. However, the data lacks value without the additional details provided by qualitative research because it doesn’t tell you anything about how your target audience thinks, feels, and acts.

Qualitative data collection is particularly relevant in the nonprofit sector as the relationships people have with the causes they support are fundamentally personal and cannot be expressed numerically. Qualitative data methods allow you to deep dive into the mindset of your audience to discover areas for growth, development, and improvement.

8 Types of Qualitative Data Collection Methods

As we have firmly established the need for qualitative data, it’s time to answer the next big question: how to collect qualitative data.

Here is a list of the most common qualitative data collection methods. You don’t need to use them all in your quest for gathering information. However, a foundational understanding of each will help you refine your research strategy and select the methods that are likely to provide the highest quality business intelligence for your organization.

1. Interviews

One-on-one interviews are one of the most commonly used data collection methods in qualitative research because they allow you to collect highly personalized information directly from the source. Interviews explore participants' opinions, motivations, beliefs, and experiences and are particularly beneficial in gathering data on sensitive topics because respondents are more likely to open up in a one-on-one setting than in a group environment.

Interviews can be conducted in person or by online video call. Typically, they are separated into three main categories:

- Structured Interviews - Structured interviews consist of predetermined (and usually closed) questions with little or no variation between interviewees. There is generally no scope for elaboration or follow-up questions, making them better suited to researching specific topics.

- Unstructured Interviews – Conversely, unstructured interviews have little to no organization or preconceived topics and include predominantly open questions. As a result, the discussion will flow in completely different directions for each participant and can be very time-consuming. For this reason, unstructured interviews are generally only used when little is known about the subject area or when in-depth responses are required on a particular subject.

- Semi-Structured Interviews – A combination of the two interviews mentioned above, semi-structured interviews comprise several scripted questions but allow both interviewers and interviewees the opportunity to diverge and elaborate so more in-depth reasoning can be explored.

While each approach has its merits, semi-structured interviews are typically favored as a way to uncover detailed information in a timely manner while highlighting areas that may not have been considered relevant in previous research efforts. Whichever type of interview you utilize, participants must be fully briefed on the format, purpose, and what you hope to achieve. With that in mind, here are a few tips to follow:

- Give them an idea of how long the interview will last

- If you plan to record the conversation, ask permission beforehand

- Provide the opportunity to ask questions before you begin and again at the end.

2. Focus Groups

Focus groups share much in common with less structured interviews, the key difference being that the goal is to collect data from several participants simultaneously. Focus groups are effective in gathering information based on collective views and are one of the most popular data collection instruments in qualitative research when a series of one-on-one interviews proves too time-consuming or difficult to schedule.

Focus groups are most helpful in gathering data from a specific group of people, such as donors or clients from a particular demographic. The discussion should be focused on a specific topic and carefully guided and moderated by the researcher to determine participant views and the reasoning behind them.

Feedback in a group setting often provides richer data than one-on-one interviews, as participants are generally more open to sharing when others are sharing too. Plus, input from one participant may spark insight from another that would not have come to light otherwise. However, here are a couple of potential downsides:

- If participants are uneasy with each other, they may not be at ease openly discussing their feelings or opinions.

- If the topic is not of interest or does not focus on something participants are willing to discuss, data will lack value.

The size of the group should be carefully considered. Research suggests over-recruiting to avoid risking cancellation, even if that means moderators have to manage more participants than anticipated. The optimum group size is generally between six and eight for all participants to be granted ample opportunity to speak. However, focus groups can still be successful with as few as three or as many as fourteen participants.

3. Observation

Observation is one of the ultimate data collection tools in qualitative research for gathering information through subjective methods. A technique used frequently by modern-day marketers, qualitative observation is also favored by psychologists, sociologists, behavior specialists, and product developers.

The primary purpose is to gather information that cannot be measured or easily quantified. It involves virtually no cognitive input from the participants themselves. Researchers simply observe subjects and their reactions during the course of their regular routines and take detailed field notes from which to draw information.

Observational techniques vary in terms of contact with participants. Some qualitative observations involve the complete immersion of the researcher over a period of time. For example, attending the same church, clinic, society meetings, or volunteer organizations as the participants. Under these circumstances, researchers will likely witness the most natural responses rather than relying on behaviors elicited in a simulated environment. Depending on the study and intended purpose, they may or may not choose to identify themselves as a researcher during the process.

Regardless of whether you take a covert or overt approach, remember that because each researcher is as unique as every participant, they will have their own inherent biases. Therefore, observational studies are prone to a high degree of subjectivity. For example, one researcher’s notes on the behavior of donors at a society event may vary wildly from the next. So, each qualitative observational study is unique in its own right.

4. Open-Ended Surveys and Questionnaires

Open-ended surveys and questionnaires allow organizations to collect views and opinions from respondents without meeting in person. They can be sent electronically and are considered one of the most cost-effective qualitative data collection tools. Unlike closed question surveys and questionnaires that limit responses, open-ended questions allow participants to provide lengthy and in-depth answers from which you can extrapolate large amounts of data.

The findings of open-ended surveys and questionnaires can be challenging to analyze because there are no uniform answers. A popular approach is to record sentiments as positive, negative, and neutral and further dissect the data from there. To gather the best business intelligence, carefully consider the presentation and length of your survey or questionnaire. Here is a list of essential considerations:

- Number of questions : Too many can feel intimidating, and you’ll experience low response rates. Too few can feel like it’s not worth the effort. Plus, the data you collect will have limited actionability. The consensus on how many questions to include varies depending on which sources you consult. However, 5-10 is a good benchmark for shorter surveys that take around 10 minutes and 15-20 for longer surveys that take approximately 20 minutes to complete.

- Personalization: Your response rate will be higher if you greet patients by name and demonstrate a historical knowledge of their interactions with your brand.

- Visual elements : Recipients can be easily turned off by poorly designed questionnaires. Besides, it’s a good idea to customize your survey template to include brand assets like colors, logos, and fonts to increase brand loyalty and recognition.

- Reminders : Sending survey reminders is the best way to improve your response rate. You don’t want to hassle respondents too soon, nor do you want to wait too long. Sending a follow-up at around the 3-7 mark is usually the most effective.

- Building a feedback loop : Adding a tick-box requesting permission for further follow-ups is a proven way to elicit more in-depth feedback. Plus, it gives respondents a voice and makes their opinion feel valued.

5. Case Studies

Case studies are often a preferred method of qualitative research data collection for organizations looking to generate incredibly detailed and in-depth information on a specific topic. Case studies are usually a deep dive into one specific case or a small number of related cases. As a result, they work well for organizations that operate in niche markets.

Case studies typically involve several qualitative data collection methods, including interviews, focus groups, surveys, and observation. The idea is to cast a wide net to obtain a rich picture comprising multiple views and responses. When conducted correctly, case studies can generate vast bodies of data that can be used to improve processes at every client and donor touchpoint.

The best way to demonstrate the purpose and value of a case study is with an example: A Longitudinal Qualitative Case Study of Change in Nonprofits – Suggesting A New Approach to the Management of Change .

The researchers established that while change management had already been widely researched in commercial and for-profit settings, little reference had been made to the unique challenges in the nonprofit sector. The case study examined change and change management at a single nonprofit hospital from the viewpoint of all those who witnessed and experienced it. To gain a holistic view of the entire process, research included interviews with employees at every level, from nursing staff to CEOs, to identify the direct and indirect impacts of change. Results were collated based on detailed responses to questions about preparing for change, experiencing change, and reflecting on change.

6. Text Analysis

Text analysis has long been used in political and social science spheres to gain a deeper understanding of behaviors and motivations by gathering insights from human-written texts. By analyzing the flow of text and word choices, relationships between other texts written by the same participant can be identified so that researchers can draw conclusions about the mindset of their target audience. Though technically a qualitative data collection method, the process can involve some quantitative elements, as often, computer systems are used to scan, extract, and categorize information to identify patterns, sentiments, and other actionable information.

You might be wondering how to collect written information from your research subjects. There are many different options, and approaches can be overt or covert.

Examples include:

- Investigating how often certain cause-related words and phrases are used in client and donor social media posts.

- Asking participants to keep a journal or diary.

- Analyzing existing interview transcripts and survey responses.

By conducting a detailed analysis, you can connect elements of written text to specific issues, causes, and cultural perspectives, allowing you to draw empirical conclusions about personal views, behaviors, and social relations. With small studies focusing on participants' subjective experience on a specific theme or topic, diaries and journals can be particularly effective in building an understanding of underlying thought processes and beliefs.

7. Audio and Video Recordings

Similarly to how data is collected from a person’s writing, you can draw valuable conclusions by observing someone’s speech patterns, intonation, and body language when you watch or listen to them interact in a particular environment or within specific surroundings.

Video and audio recordings are helpful in circumstances where researchers predict better results by having participants be in the moment rather than having them think about what to write down or how to formulate an answer to an email survey.

You can collect audio and video materials for analysis from multiple sources, including:

- Previously filmed records of events

- Interview recordings

- Video diaries

Utilizing audio and video footage allows researchers to revisit key themes, and it's possible to use the same analytical sources in multiple studies – providing that the scope of the original recording is comprehensive enough to cover the intended theme in adequate depth.

It can be challenging to present the results of audio and video analysis in a quantifiable form that helps you gauge campaign and market performance. However, results can be used to effectively design concept maps that extrapolate central themes that arise consistently. Concept Mapping offers organizations a visual representation of thought patterns and how ideas link together between different demographics. This data can prove invaluable in identifying areas for improvement and change across entire projects and organizational processes.

8. Hybrid Methodologies

It is often possible to utilize data collection methods in qualitative research that provide quantitative facts and figures. So if you’re struggling to settle on an approach, a hybrid methodology may be a good starting point. For instance, a survey format that asks closed and open questions can collect and collate quantitative and qualitative data.

A Net Promoter Score (NPS) survey is a great example. The primary goal of an NPS survey is to collect quantitative ratings of various factors on a score of 1-10. However, they also utilize open-ended follow-up questions to collect qualitative data that helps identify insights into the trends, thought processes, reasoning, and behaviors behind the initial scoring.

Collect and Collate Actionable Data with UpMetrics

Most nonprofits believe data is strategically important. It has been statistically proven that organizations with advanced data insights achieve their missions more efficiently. Yet, studies show that despite 90% of organizations collecting data, only 5% believe internal decision-making is data-driven. At UpMetrics, we’re here to help you change that.

Unlock your organization's impact potential with an Impact Framework UpMetrics' next generation Impact Measurement and Management platform makes measuring, optimizing, and showcasing your organization's impact easier than ever before.

As part of our IMM Suite's free Starter Plan, we're excited to offer mission-driven organizations no-cost access to our new Impact Framework Builder functionality so that you can define how you're thinking about impact tied to your mission and vision.

Disrupting Tradition

Download our case study to discover how the Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation is using a Learning Mindset to Support Grantees in Measuring Impact

Understanding the Meaning of Qualitative Research: Definition & Methods

Dive into the world of qualitative research with this insightful article that unpacks its definition, explores various methodologies, and highlights its significance in uncovering deep, nuanced insights beyond numbers..

Defining Qualitative Research

Qualitative research is a method of inquiry that focuses on understanding the meaning and experience behind various phenomena. It seeks to gain insights into specific behaviors, emotions, and thoughts by gathering non-numerical data. This approach often contrasts with quantitative research, which relies heavily on statistical analyses and numerical data to arrive at conclusions.

The essence of qualitative research lies in its depth and complexity. Researchers typically aim to comprehend not just “what” occurs, but also “how” and “why” certain phenomena manifest. By utilizing diverse methods such as interviews, observations, and textual analysis, qualitative research can reveal insights that statistical data might overlook. For instance, in studying consumer behavior, qualitative methods can uncover the motivations behind purchasing decisions, providing a richer context that numbers alone cannot convey. This nuanced understanding is invaluable for fields such as marketing, psychology, and sociology, where human behavior is central.

The Core Principles of Qualitative Research

One of the fundamental principles of qualitative research is that reality is subjective and constructed through social interactions. As such, qualitative researchers prioritize the perspectives and experiences of individuals within specific contexts. They recognize that an individual’s reality can vary based on cultural, social, and personal factors. This principle encourages researchers to adopt a reflexive approach, being aware of their biases and how these may influence the research process. By doing so, they can better appreciate the complexities of the human experience and ensure that their findings reflect the voices of the participants authentically.

Another principle is the commitment to a holistic understanding of the research subject. It focuses on the intricacies of human experiences, capturing the richness and variety of those experiences. This often means engaging with subjects in their natural environment, allowing for a more authentic view of their situations. For example, ethnographic studies may involve researchers immersing themselves in a community to observe and participate in daily life, thereby gaining insights that are often missed in more structured research settings. Such immersive techniques not only deepen the understanding of the subject matter but also foster a sense of trust and rapport between the researcher and participants, enhancing the quality of the data collected.

Key Terminology in Qualitative Research

Familiarity with key terms is crucial when navigating qualitative research. One of these terms is "data saturation," which refers to the point where additional data collection yields little to no new information. Reaching data saturation typically signifies that the researcher has comprehensively explored the research questions. It is a critical milestone that helps researchers determine the adequacy of their sample size and the richness of the data collected, ensuring that the findings are robust and well-supported.

Another key term is “phenomenology,” which studies individuals’ experiences, particularly concerning specific phenomena. This approach emphasizes the subjective nature of experience and seeks to understand how individuals make sense of their lived experiences. Understanding these terms and concepts helps researchers communicate their findings effectively, enhancing the overall rigor of qualitative research. Additionally, terms like "grounded theory" and "narrative analysis" further enrich the vocabulary of qualitative research, each representing unique methodologies that contribute to the diverse landscape of qualitative inquiry. By mastering this terminology, researchers can articulate their methodologies and findings with clarity, fostering a deeper engagement with their audience and the broader academic community.

The Importance of Qualitative Research

Qualitative research plays a significant role in several fields, including social sciences, healthcare, education, and market research. It is particularly valuable when exploring complex issues requiring in-depth understanding, such as cultural practices, social dynamics, or customer experiences.

The insights gleaned from qualitative research can inform policy-making, improve practice, and drive innovation. By providing a deeper understanding of the human experience, qualitative research can significantly influence how services are designed and delivered. Moreover, it fosters critical thinking and reflection among researchers and practitioners alike.

Benefits of Qualitative Research

One major benefit of qualitative research is its ability to uncover nuances that quantitative research may not reveal. It allows for exploration of attitudes, motivations, and feelings, leading to a richer understanding of the subject matter. This depth of insight can inform strategies that better align with individuals’ needs.

Furthermore, qualitative research is flexible, accommodating changes in direction as new insights emerge. This adaptability can lead to unexpected discoveries that enhance the research outcome significantly, making it a dynamic and engaging process.

Limitations of Qualitative Research

Despite its strengths, qualitative research does have limitations. One prominent challenge is subjectivity, as researchers’ biases may influence data collection and interpretation. Consequently, it is essential to maintain reflexivity throughout the research process to mitigate potential biases.

Moreover, generalizability can be an issue. Due to the typically smaller sample sizes and context-specific nature of qualitative studies, findings may not be easily extrapolated to broader populations. Recognizing these limitations is crucial for framing and contextualizing research outcomes effectively.

Different Methods in Qualitative Research

Qualitative research comprises various methodologies, each with unique strengths, characteristics, and applications. The choice of a method often depends on the research question, objectives, and the environment in which the study is conducted.

This section explores several prevalent methods that researchers may use to conduct qualitative investigations, illustrating the diversity and adaptability inherent in qualitative research.

Interviews and Focus Groups

Interviews are among the most popular qualitative research methods. They can be structured, semi-structured, or unstructured, allowing researchers to probe deeply into participants’ thoughts and experiences. The personal nature of interviews means they often yield rich, detailed data.

Focus groups also play a crucial role in qualitative research. In this method, a facilitated discussion among a group of participants provides insights into shared experiences and collective opinions. This interactive setting fosters dynamic discussions that can surface varying perspectives and spark new ideas.

Observations and Ethnography

Observation involves watching and recording behavior in natural settings, allowing researchers to gather contextual information that could be missed through verbal methods. Ethnography extends this approach, requiring extended immersion in the culture or environment being studied. This deep engagement yields rich data on social interactions, norms, and practices.

Both methods are incredibly effective for capturing real-world dynamics and complexities, helping researchers to understand phenomena in their natural context.

Textual and Content Analysis

Textual analysis focuses on examining written or spoken content to interpret meaning and context. Researchers analyze various texts—such as interviews, papers, and social media content—to uncover themes and patterns that provide insights into societal issues or behaviors.

Content analysis, while somewhat similar, quantitatively evaluates the presence of certain words, themes, or concepts within qualitative data. By combining qualitative and quantitative approaches, researchers can yield a more comprehensive understanding of the messages conveyed in the content being analyzed.

Choosing the Right Method for Your Research

Selecting the appropriate qualitative method is crucial for the success of a research project. Multiple factors come into play, including the research question, objectives, and available resources. Each method has its strengths and weaknesses, and understanding these helps in making an informed choice.

Factors to Consider When Selecting a Method

When choosing a method, consider the nature of your research question. If your focus is on individual experiences or personal narratives, semi-structured interviews or ethnography might be most suitable. Conversely, if you aim to explore group dynamics, focus groups may be more effective.

Additionally, the available resources, including time and expertise, should guide your selection. Some methods, like ethnography, require significant time and commitment, while others, like interviews, may be more manageable within tighter timelines.

Aligning Your Research Question with Your Method

It's essential that your chosen method aligns well with your research question. When this alignment is achieved, the collected data will be more relevant and meaningful. Engaging in preliminary reviews of literature can help clarify what methods have worked effectively in similar studies, guiding your decision-making process.

This careful alignment ensures that your qualitative research can effectively address the nuances of your questions, leading to more impactful conclusions and practical applications.

Analyzing Qualitative Data

After data collection, the analysis phase is where qualitative research truly transforms into knowledge. This is a critical stage where patterns are identified, themes are developed, and interpretations are constructed. Various strategies exist for analyzing qualitative data, each designed to illuminate specific aspects of the information gathered.

Thematic Analysis

Thematic analysis is one of the most commonly used methods in qualitative research. Researchers identify recurring themes across the dataset, allowing them to understand key insights relevant to the research question. This method provides flexibility and can be applied to a variety of qualitative data forms.

To conduct thematic analysis effectively, researchers must be systematic in their approach, allowing for detailed coding and categorization that ultimately reveals the nuances of the data.

Grounded Theory

Grounded theory is an approach particularly valuable in exploring new areas of inquiry. This analytic method involves developing theories based directly on the data collected, rather than starting with a pre-existing hypothesis. Researchers iteratively analyze data, often developing multiple rounds of coding to establish patterns and theoretical insights.

This approach is particularly effective in areas where existing theories may not adequately explain the phenomena under investigation, making it a powerful tool for discovering novel insights.

Narrative Analysis

Narrative analysis focuses on understanding the stories individuals tell about their experiences. By analyzing how narratives are constructed, researchers can gain insights into the meanings individuals ascribe to their lives and experiences. This method highlights the power of storytelling and the significance of context in shaping narratives.

By employing narrative analysis, researchers can uncover rich layers of meaning that deepen their understanding of human experiences, making it a compelling approach in qualitative research.

As you delve into the complexities of qualitative research and harness its power to uncover profound insights, consider the role of sophisticated data management in enhancing your analytical capabilities. CastorDoc is designed to support researchers and businesses alike with advanced governance, cataloging, and lineage features, complemented by a user-friendly AI assistant. This powerful tool enables self-service analytics, allowing you to navigate through vast amounts of qualitative data with ease. Whether you're looking to streamline your data governance lifecycle or empower your business decisions with accessible, understandable data, try CastorDoc today and experience a revolution in data management and utilization.

.png)

Write SQL in autopilot with our SQL Assistant. CastorDoc's AI corrects, improves, formats your SQL for better performance.

You might also like

%202.png)

This article covers end-to-end data lineage, also called “hybrid lineage”. End-to-end lineage tracks your data's complete journey - from raw warehouse tables, through transformation layers, to final visualization in dashboards.

This article explores how AI is transforming employees into data analysts and why skilled professionals are still key for advanced analytics and strategic insights

This article explores the strategic value and practical use cases of data lineage, demonstrating how it enhances data governance, compliance, migration, and overall data management efficiency.

%202.png)

Discover how AI analytics is transforming business decision-making. Learn about its evolution, benefits, and challenges, plus get a 3-step guide to implementation.

Discover how AI is transforming data self-service from a DIY approach to a more efficient "buffet" model, where users can easily access and customize expert-created analyses, addressing key challenges in data accessibility and trust.

%202.png)

Discover how AI is transforming data analytics by connecting users to existing insights through natural language search.

%202.png)

Discover how to evaluate AI solutions for your organization by understanding the autonomy spectrum and determining the optimal level of automation for various roles. Learn how to balance trust and return on investment with AI systems.

What if you could get data insights simply by asking in Slack? 👀 Meet CastorDoc's AI Assistant!

Struggling with adopting the power of generative AI for data management? This article delves into preparing for GenAI: ensuring the right tech and data are in place, and educating employees on its implications for the business.

Struggling to make your organization truly data-driven? Discover how to escape the self-service analytics paradox, where increased data access leads to more chaos and confusion. Learn a practical approach that balances empowering business users with maintaining strong data governance.

.png)

Discover why current AI chatbots struggle to deliver on their promises and learn how to bridge the gap. Explore the vital role of clear business knowledge and metadata in creating trustworthy data assistants.

Snowflake Horizon represents a leap forward in data governance, offering a comprehensive suite of compliance, security, privacy, and interoperability capabilities. By integrating with Snowflake, CastorDoc extends these capabilities, enabling customers to govern and secure their data across diverse environments and systems.

Get in Touch to Learn More

“[I like] The easy to use interface and the speed of finding the relevant assets that you're looking for in your database. I also really enjoy the score given to each table, [which] lets you prioritize the results of your queries by how often certain data is used.” - Michal P., Head of Data

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it's official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Browse Titles

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-.

StatPearls [Internet].

Qualitative study.

Steven Tenny ; Janelle M. Brannan ; Grace D. Brannan .

Affiliations

Last Update: September 18, 2022 .

- Introduction

Qualitative research is a type of research that explores and provides deeper insights into real-world problems. [1] Instead of collecting numerical data points or intervening or introducing treatments just like in quantitative research, qualitative research helps generate hypothenar to further investigate and understand quantitative data. Qualitative research gathers participants' experiences, perceptions, and behavior. It answers the hows and whys instead of how many or how much. It could be structured as a standalone study, purely relying on qualitative data, or part of mixed-methods research that combines qualitative and quantitative data. This review introduces the readers to some basic concepts, definitions, terminology, and applications of qualitative research.

Qualitative research, at its core, asks open-ended questions whose answers are not easily put into numbers, such as "how" and "why." [2] Due to the open-ended nature of the research questions, qualitative research design is often not linear like quantitative design. [2] One of the strengths of qualitative research is its ability to explain processes and patterns of human behavior that can be difficult to quantify. [3] Phenomena such as experiences, attitudes, and behaviors can be complex to capture accurately and quantitatively. In contrast, a qualitative approach allows participants themselves to explain how, why, or what they were thinking, feeling, and experiencing at a particular time or during an event of interest. Quantifying qualitative data certainly is possible, but at its core, qualitative data is looking for themes and patterns that can be difficult to quantify, and it is essential to ensure that the context and narrative of qualitative work are not lost by trying to quantify something that is not meant to be quantified.

However, while qualitative research is sometimes placed in opposition to quantitative research, where they are necessarily opposites and therefore "compete" against each other and the philosophical paradigms associated with each other, qualitative and quantitative work are neither necessarily opposites, nor are they incompatible. [4] While qualitative and quantitative approaches are different, they are not necessarily opposites and certainly not mutually exclusive. For instance, qualitative research can help expand and deepen understanding of data or results obtained from quantitative analysis. For example, say a quantitative analysis has determined a correlation between length of stay and level of patient satisfaction, but why does this correlation exist? This dual-focus scenario shows one way in which qualitative and quantitative research could be integrated.

Qualitative Research Approaches

Ethnography