Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

1.5 The Purposes of Punishment

Learning objective.

- Ascertain the effects of specific and general deterrence, incapacitation, rehabilitation, retribution, and restitution.

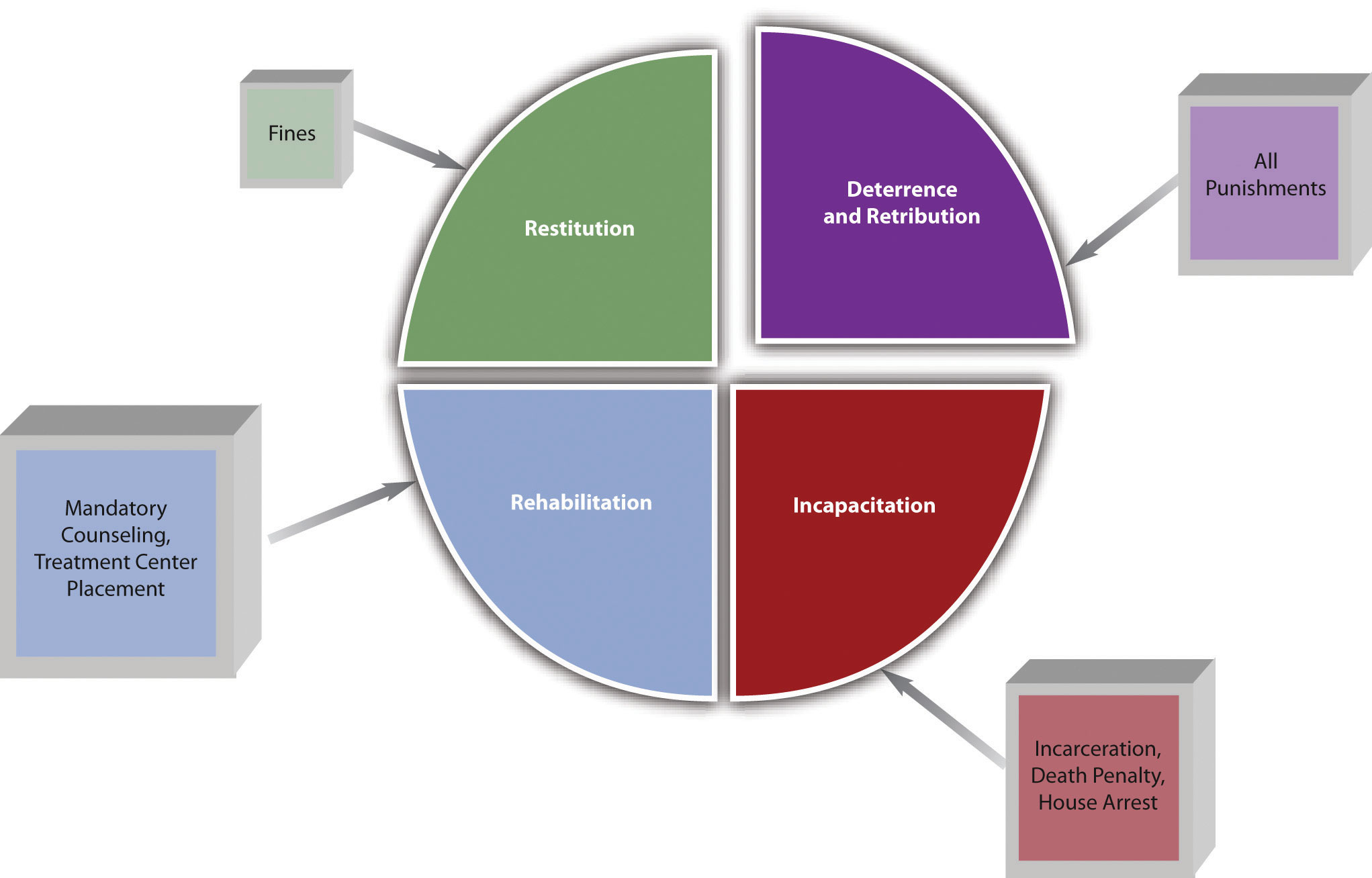

Punishment has five recognized purposes: deterrence , incapacitation , rehabilitation , retribution , and restitution .

Specific and General Deterrence

Deterrence prevents future crime by frightening the defendant or the public . The two types of deterrence are specific and general deterrence . Specific deterrence applies to an individual defendant . When the government punishes an individual defendant, he or she is theoretically less likely to commit another crime because of fear of another similar or worse punishment. General deterrence applies to the public at large. When the public learns of an individual defendant’s punishment, the public is theoretically less likely to commit a crime because of fear of the punishment the defendant experienced. When the public learns, for example, that an individual defendant was severely punished by a sentence of life in prison or the death penalty, this knowledge can inspire a deep fear of criminal prosecution.

Incapacitation

Incapacitation prevents future crime by removing the defendant from society. Examples of incapacitation are incarceration, house arrest, or execution pursuant to the death penalty.

Rehabilitation

Rehabilitation prevents future crime by altering a defendant’s behavior. Examples of rehabilitation include educational and vocational programs, treatment center placement, and counseling. The court can combine rehabilitation with incarceration or with probation or parole. In some states, for example, nonviolent drug offenders must participate in rehabilitation in combination with probation, rather than submitting to incarceration (Ariz. Rev. Stat., 2010). This lightens the load of jails and prisons while lowering recidivism , which means reoffending.

Retribution

Retribution prevents future crime by removing the desire for personal avengement (in the form of assault, battery, and criminal homicide, for example) against the defendant. When victims or society discover that the defendant has been adequately punished for a crime, they achieve a certain satisfaction that our criminal procedure is working effectively, which enhances faith in law enforcement and our government.

Restitution

Restitution prevents future crime by punishing the defendant financially . Restitution is when the court orders the criminal defendant to pay the victim for any harm and resembles a civil litigation damages award. Restitution can be for physical injuries, loss of property or money, and rarely, emotional distress. It can also be a fine that covers some of the costs of the criminal prosecution and punishment.

Figure 1.4 Different Punishments and Their Purpose

Key Takeaways

- Specific deterrence prevents crime by frightening an individual defendant with punishment. General deterrence prevents crime by frightening the public with the punishment of an individual defendant.

- Incapacitation prevents crime by removing a defendant from society.

- Rehabilitation prevents crime by altering a defendant’s behavior.

- Retribution prevents crime by giving victims or society a feeling of avengement.

- Restitution prevents crime by punishing the defendant financially.

Answer the following questions. Check your answers using the answer key at the end of the chapter.

- What is one difference between criminal victims’ restitution and civil damages?

- Read Campbell v. State , 5 S.W.3d 693 (1999). Why did the defendant in this case claim that the restitution award was too high? Did the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals agree with the defendant’s claim? The case is available at this link: http://scholar.google.com/scholar_case?case=11316909200521760089&hl=en&as_sdt=2&as_vis=1&oi=scholarr .

Ariz. Rev. Stat. §13-901.01, accessed February 15, 2010, http://law.justia.com/arizona/codes/title13/00901-01.html .

Criminal Law Copyright © 2015 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Legal Dictionary

The Law Dictionary for Everyone

Specific Deterrence

Specific deterrence is a type of punishment that is meant to discourage future criminal behavior in a person being charged with a crime. For example, specific deterrence is used to prevent an offender from committing the same crime in the future. Punishments associated with specific deterrence may include fines, prison sentences, or both, and the severity of the punishment typically determines the effectiveness of the deterrence. To explore this concept, consider the following specific deterrence definition.

Definition of Specific Deterrence

- A punishment aimed at preventing an offender from engaging in criminal behavior again in the future.

What is Deterrence

Deterrence refers to the act of discouraging people from engaging in criminal behavior. This is typically done by assigning a suitable punishment for the behavior. While specific deterrence is customized for the individual who committed a crime in particular, deterrence is intended to sway the general public as a whole from participating in illicit behavior. Deterrence works to make people think twice about breaking the law.

This is how traffic laws work. When the public is aware that they will receive a ticket or, in some cases, suspension of their licenses, for not obeying traffic laws, they are more likely to obey the laws and to drive carefully. The traffic laws in this situation act as a general deterrence to prevent people from engaging in illegal activity while behind the wheel.

Many times, judges will impose sentences that aim to provide both specific and general deterrence. This way, not only are they dissuading the offenders before them from breaking the law again, but they are also sending a message to the general public that this will be their punishment if they choose to commit the same or a similar crime.

Types of Deterrence

There are two main types of deterrence: (1) specific deterrence, and (2) general deterrence. Specific deterrence is a type of deterrence that is aimed at the specific individual being charged with a crime. General deterrence is a type of deterrence that is used to discourage the public at large from committing the same crime, or a similar one, to that which was committed by the person being sentenced.

The objective of deterrence is to make the punishment harsh enough that the public will fear receiving a similar punishment, and will be dissuaded from engaging in similar criminal behavior in the future. Retributivism is a form of punishment that differs from deterrence. Instead, retributivism focuses on handing down a punishment that is appropriate to the crime that was committed.

The idea of specific deterrence is that, if an offender receives a severe punishment for his wrongdoings, then he will not be tempted to commit a similar crime in the future. For example, specific deterrence dictates that, if an armed robber receives a harsh sentence of eight years in prison, he will be less likely to commit armed robbery again when he eventually gets out. However, research has shown that the effectiveness of specific deterrence varies on a case-by-case basis. On a related note, the three strikes law is effective as a deterrent in that courts are permitted to give out harsher sentences to offenders who have been convicted of three or more serious crimes.

General Deterrence

General deterrence focuses more on teaching the general public a lesson, rather than just the individual being charged with the crime. The idea is that, if the individual is punished harshly, the public will see that harsh punishment and be dissuaded from engaging in the same or similar activity. A good example of this is the death penalty. When a criminal is sentenced to death for his crime, such a sentence may dissuade the general public from committing the same or similar crime.

Retributivism

Retributivism is a legal theory that deals with assigning a punishment to an offender that fits his crime. Retributivism differs from deterrence in that, while deterrence aims at preventing crime, retributivism is more concerned about punishing people for the crimes they have already committed. Some punishments can be both deterrents and retributive. For instance, an armed robber may receive a prison sentence of six to eight years, which is a sentence that works to deter him from committing a similar crime in the future, and is also an appropriate punishment to fit the crime.

Effectiveness of Specific Deterrence

Interestingly, the effectiveness of specific deterrence is a point of debate. For one thing, the certainty of being caught has been proven to be a far more effective deterrent than even the harshest of punishments. Also, just because an offender is sentenced to prison, this does not ensure the effectiveness of specific deterrence.

Prison sentences, especially long ones, may have the opposite effect from that which is expected in that offenders may become desensitized to being in prison. The offender may feel like he has already survived prison once before, so he can surely do it again. Prisoners can also become institutionalized and feel like they are unable to survive on the outside. They will therefore commit a crime just to be able to return to prison, as they consider prison to be their home.

Another mark against the effectiveness of specific deterrence is that increasing the severity of an offender’s punishment does not actually work to deter crime. This is because, on average, criminals tend not to know a lot about the punishments associated with the crimes they commit. Even the death penalty cannot be proven to deter criminals from engaging in criminal activity that could result in the ultimate punishment: the loss of their lives.

Specific Deterrence Example Involving the Three Strikes Law

An example of specific deterrence can be found in a case wherein a judge handed down a particularly harsh sentence in order to teach a juvenile criminal defendant a lesson. In July of 2003, 16-year-old Terrance Jamar Graham was arrested after he and three of his peers tried to rob a restaurant in Jacksonville, Florida. One of the boys struck the manager of the restaurant in the head with a metal bar. The manager required stitches for his head injury. Ultimately, no money was stolen.

Under Florida law, it is up to the prosecutor whether to charge a 16-year-old as an adult or a juvenile for a felony crime. The prosecutor in this case elected to charge Graham as an adult, presumably to teach him a lesson. Graham was charged with armed burglary with assault or battery , which is a first-degree felony that carries the maximum penalty of life in prison without parole . Graham was also charged with a second-degree felony – attempted armed robbery – which comes with a maximum penalty of 15 years in prison.

Graham pled guilty to both charges and wrote a letter to the court wherein he detailed his intentions to turn his life around and do everything possible to join the NFL. The trial court accepted Graham’s plea and in an effort at specific deterrence, sentenced him to concurrent 3-year terms of probation . He was ordered to spend the first twelve months of his probation in the county jail, but he was credited with time served and was released six months later.

On December 2, 2004, Graham was arrested again on charges associated with violating his parole, including possessing a firearm, just before he was about to turn 18. Hearings were held on these violations the following year, and the judge who presided over these violations was not the same judge who had accepted his earlier plea.

Here, the judge found Graham guilty of the armed burglary and attempted armed robbery charges against him and sentenced him to the maximum sentence for each charge: life in prison for the armed burglary, and 15 years for the attempted armed robbery. The judge’s reasoning was that Graham had chosen to throw his life away, and that he left the court with no choice but to protect the community from the illicit path he was following. Florida abolished its parole system back in 2003, which means that a defendant who receives a life sentence has no possibility of being released early, save for a rare exception to the rule.

Graham filed a motion in the trial court to challenge the sentence under the Eighth Amendment . However, the motion was denied after the trial court failed to rule on it within the requisite 60-day timeframe. The First District Court of Appeal of Florida affirmed the motion’s dismissal , holding that Graham’s sentence was not disproportionate to the crimes he committed. Further, the court believed that Graham was incapable of being rehabilitated, that despite having a strong family structure as his support, he rejected the second chance given to him by the trial court and continued committing crimes “at an escalating pace.”

The U.S. Supreme Court granted certiorari to hear the case and, upon review, reversed the decision of the First District Court of Appeal of Florida and remanded the case back to the lower court. Said the Court in its decision:

“The State contends that this study’s tally is inaccurate because it does not count juvenile offenders who were convicted of both a homicide and a nonhomicide offense, even when the offender received a life without parole sentence for the nonhomicide…This distinction is unpersuasive. Juvenile offenders who committed both homicide and nonhomicide crimes present a different situation for a sentencing judge than juvenile offenders who committed no homicide. It is difficult to say that a defendant who receives a life sentence on a nonhomicide offense but who was at the same time convicted of homicide is not in some sense being punished in part for the homicide when the judge makes the sentencing determination. The instant case concerns only those juvenile offenders sentenced to life without parole solely for a nonhomicide offense.”

The Court concluded its decision by saying:

“The Constitution prohibits the imposition of a life without parole sentence on a juvenile offender who did not commit homicide. A State need not guarantee the offender eventual release, but if it imposes a sentence of life it must provide him or her with some realistic opportunity to obtain release before the end of that term.”

Related Legal Terms and Issues

- Felony – A crime, often involving violence, regarded as more serious than a misdemeanor . Felony crimes are usually punishable by imprisonment more than one year.

- Misdemeanor – A criminal offense less serious than a felony.

- Writ of Certiorari – An order issued by a higher court demanding a lower court forward all records of a specific case for review.

An official website of the United States government, Department of Justice.

Here's how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock A locked padlock ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

NCJRS Virtual Library

Reconceptualization of general and specific deterrence, additional details, no download available, availability, related topics.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Key Takeaways. Specific deterrence prevents crime by frightening an individual defendant with punishment. General deterrence prevents crime by frightening the public with the punishment of an individual defendant. Incapacitation prevents crime by removing a defendant from society.

Specific deterrence discourages individuals from committing crimes because they have learned through personal experience (i.e., by being punished) that the cost for their criminal behaviors is too high (Akers & Sellers, 2009).

The concept of specific deterrence proposes that individuals who commit crime(s) and are caught and punished will be deterred from future criminal activ ity. On the other hand, general deterrence suggests that the general population will be deterred from offending when they are aware of others being apprehended and punished.

Specific deterrence is a type of punishment that is meant to discourage future criminal behavior in a person being charged with a crime. For example, specific deterrence is used to prevent an offender from committing the same crime in the future.

Deterrence — the crime prevention effects of the threat of punishment — is a theory of choice in which individuals balance the benefits and costs of crime. In his 2013 essay, “Deterrence in the Twenty-First Century,” Daniel S. Nagin succinctly summarized the current state of theory and empirical knowledge about deterrence. [1]

Specific deterrence targets individual offenders with the aim of preventing them from committing future crimes through tailored punishments. In contrast, general deterrence aims to dissuade society as a whole by punishing offenders publicly to serve as a warning to others.

"General" deterrence refers to the effects of legal punishment on the general public (potential offenders), and "specific" deterrence refers to the effects of legal punishment on those individuals who actually undergo the punishment.

Classical deterrence theory distinguishes two main mechanisms through which punishment can deter crime: specific deterrence and general deterrence. Specific deterrence is the concept of deterrence through first-hand punishment.

Specific deterrence is the act of sending a juvenile who has been convicted to serve a sentence in an incarnated facility in effort to deter or convince them to not continue to exhibit their criminal behavior.

This essay about specific deterrence discusses its role in preventing individuals who have already committed a crime from reoffending. It explains that specific deterrence operates on the principle that the unpleasantness of punishment, such as imprisonment or fines, discourages further criminal behavior.