Founders Online --> [ Back to normal view ]

The federalist no. 29, [9 january 1788], the federalist no. 29 1.

[New York, January 9, 1788]

To the People of the State of New-York.

THE power of regulating the militia and of commanding its services in times of insurrection and invasion are natural incidents to the duties of superintending the common defence, and of watching over the internal peace of the confederacy.

It requires no skill in the science of war to discern that uniformity in the organization and discipline of the militia would be attended with the most beneficial effects, whenever they were called into service for the public defence. It would enable them to discharge the duties of the camp and of the field with mutual intelligence and concert; an advantage of peculiar moment in the operations of an army; And it would fit them much sooner to acquire the degree of proficiency in military functions, which would be essential to their usefulness. This desirable uniformity can only be accomplished by confiding the regulation of the militia to the direction of the national authority. It is therefore with the most evident propriety that the plan of the Convention proposes to empower the union “to provide for organizing, arming and disciplining the militia, and for governing such part of them as may be employed in the service of the United States, reserving to the states respectively the appointment of the officers and the authority of training the militia according to the discipline prescribed by Congress .”

Of the different grounds which have been taken in opposition to the 2 plan of the Convention, 3 there is none that was so little to have been expected, or is so untenable in itself, as the one from which 4 this particular provision has been attacked. If a well regulated militia be the most natural defence of a free country, it ought certainly to be under the regulation and at the disposal of that body which is constituted the guardian of the national security. If standing armies are dangerous to liberty, an efficacious power over the militia, in the 5 body to whose care the protection of the State is committed, 6 ought as far as possible to take away the inducement and the pretext to such unfriendly institutions. If the fœderal government can command the aid of the militia in those emergencies which call for the military arm in support of the civil magistrate, it can the better dispense with the employment of a different kind of force. If it cannot avail itself of the former, it will be obliged to recur to the latter. To render an army unnecessary will be a more certain method of preventing its existence than a thousand prohibitions upon paper.

In order to cast an odium upon the power of calling forth the militia to execute the Laws of the Union, it has been remarked that there is no where any provision in the proposed Constitution for calling out 7 the POSSE COMITATUS to assist the magistrate in the execution of his duty; whence it has been inferred that military force was intended to be his only auxiliary. There is a striking incoherence in the objections which have appeared, and sometimes even from the same quarter, not much calculated to inspire a very favourable opinion of the sincerity or fair dealing of their authors. The same persons who tell us in one breath that the powers of the federal government will be despotic and unlimited, inform us in the next that it has not authority sufficient even to call out the POSSE COMITATUS. The latter fortunately is as much short of the truth as the former exceeds it. It would be as absurd to doubt that a right to pass all laws necessary and proper to execute its declared powers would include that of requiring the assistance of the citizens to the officers who may be entrusted with the execution of those laws; as it would be to believe that a right to enact laws necessary and proper for the imposition and collection of taxes would involve that of varying the rules of descent and 8 alienation of landed property or of abolishing the trial by jury in cases relating to it. It being therefore evident that the supposition of a want of power to require the aid of the POSSE COMITATUS is entirely destitute of colour, it will follow that the conclusion which has been drawn from it, in its application to the authority of the federal government over the militia is as uncandid as it is illogical. What reason could there be to infer that force was intended to be the sole instrument of authority merely because there is a power to make use of it when necessary? What shall we think of the motives which could induce men of sense to reason in this 9 manner? How shall we prevent a conflict between charity and judgment? 10

By a curious refinement upon the spirit of republican jealousy, we are even taught to apprehend danger from the militia itself in the hands of the federal government. It is observed that select corps may be formed, composed of the young and 11 ardent, who may be rendered subservient to the views of arbitrary power. What plan for the regulation of the militia may be pursued by the national government is impossible to be foreseen. But so far from viewing the matter in the same light with those who object to select corps as dangerous, were the Constitution ratified, and were I to deliver my sentiments to a member of the federal legislature from this State 12 on the subject of a militia establishment, I should hold to him in substance the following discourse:

“The project of disciplining all the militia of the United States is as futile as it would be injurious, if it were capable of being carried into execution. A tolerable expertness in military movements is a business that requires time and practice. It is not a day or even 13 a week 14 that will suffice for the attainment of it. To oblige the great body of the yeomanry and of the other classes of the citizens to be under arms for the purpose of going through military exercises and evolutions as often as might be necessary, to acquire the degree of perfection which would intitle them to the character of a well regulated militia, would be a real grievance to the people, and a serious public inconvenience and loss. It would form an annual deduction from the productive labour of the country to an amount which, calculating upon the present numbers of the people, would not fall far short of the whole expence of the civil establishments of all the States. 15 To attempt a thing which would abridge the mass of labour and industry to so considerable an extent would be unwise; and the experiment, if made, could not succeed, because it would not long be endured. Little more can reasonably be aimed at with respect to the people at large than to have them properly armed and equipped; and in order to see that this be not neglected, it will be necessary to assemble them once or twice in the course of a year.

“But though the scheme of disciplining the whole nation must be abandoned as mischievous or impracticable; yet it is a matter of the utmost importance that a well digested plan should as soon as possible be adopted for the proper establishment of the militia. The attention of the government ought particularly to be directed to the formation of a select corps of moderate size 16 upon such principles as will really fit it 17 for service in case of need. By thus circumscribing the plan it will be possible to have an excellent body of well trained militia ready to take the field whenever the defence of the State shall require it. This will not only lessen the call for military establishments; but if circumstances should at any time oblige the government to form an army of any magnitude, that army can never be formidable to the liberties of the people, while there is a large body of citizens little if at all inferior to them in discipline and the use of arms, who stand ready to defend their own rights and those of their fellow citizens. This appears to me the only substitute that can be devised for a standing army; 18 the best possible security against it, if it should exist.”

Thus differently from the adversaries of the proposed constitution should I reason on the same subject; deducing arguments of safety from the very sources which they represent as fraught with danger and perdition. But how the national Legislature may reason on the point is a thing which neither they nor I can foresee.

There is something so far fetched and so extravagant in the idea of danger to liberty from the militia, that one is at a loss whether to treat it with gravity or with raillery; whether to consider it as a mere trial of skill, like the paradoxes of rhetoricians, as a disingenuous artifice to instill prejudices at any price or as the serious offspring of political fanaticism. Where in the name of common sense are our fears to end if we may not trust our sons, our brothers, our neighbours, our fellow-citizens? What shadow of danger can there be from men who are daily mingling with the rest of their countrymen; and who participate with them in the same feelings, sentiments, habits and interests? What reasonable cause of apprehension can be inferred from a power in the Union to prescribe regulations for the militia and to command its services when necessary; while the particular States are to have the sole and exclusive appointment of the officers? If it were possible seriously to indulge a jealousy of the militia upon any conceivable establishment under the Fœderal Government, the circumstance of the officers being in the appointment of the States ought at once to extinguish it. There can be no doubt that this circumstance will always secure to them a preponderating influence over the militia.

In reading many of the publications against the Constitution, a man is apt to imagine that he is perusing some ill written tale or romance; which instead of natural and agreeable images exhibits to the mind nothing but frightful and distorted shapes—Gorgons Hydras and Chimeras dire—discoloring and disfiguring whatever it represents and transforming every thing it touches into a monster.

A sample of this is to be observed in the exaggerated and improbable suggestions which have taken place respecting the power of calling for the services of the militia. That of New-Hampshire is to be marched to Georgia, of Georgia to New Hampshire, of New-York to Kentuke and of Kentuke to Lake Champlain. Nay the debts due to the French and Dutch are to be paid in Militia-men instead of Louis d’ors and ducats. At one moment there is to be a large army to lay prostrate the liberties of the people; at another moment the militia of Virginia are to be dragged from their homes five or six hundred miles to tame the republican contumacy of Massachusetts; and that of Massachusetts is to be transported an equal distance to subdue the refractory haughtiness of the aristocratic Virginians. Do the persons, who rave at this rate, imagine, that their art or their eloquence can impose any conceits 19 or absurdities upon the people of America for infallible truths?

If there should be an army to be made use of as the engine of despotism what need of the militia? If there should be no army, whither would the militia, irritated by being called upon 20 to undertake a distant and hopeless 21 expedition for the purpose of rivetting the chains of slavery upon a part of their countrymen direct their course, but to the seat of the tyrants, who had meditated so foolish as well as so wicked a project; to crush them in their imagined intrenchments of power and to 22 make them an example of the just vengeance of an abused and incensed people? Is this the way in which usurpers stride to dominion over a numerous and enlightened nation? Do they begin by exciting the detestation of the very instruments of their intended usurpations? Do they usually commence their career by wanton and disgustful acts of power calculated to answer no end, but to draw upon themselves universal hatred and execration? Are suppositions of this sort the sober admonitions of discerning patriots to a discerning people? Or are they the inflammatory ravings of chagrined incendiaries or distempered enthusiasts? If we were even to suppose the national rulers actuated by the most ungovernable ambition, it is impossible to believe that they would employ such preposterous means to accomplish their designs.

In times of insurrection or invasion it would be natural and proper that the militia of a neighbouring state should be marched into another to resist a common enemy or to guard the republic against the violences of faction or sedition. This was frequently the case in respect to the first object in the course of the late war; and this mutual succour is indeed a principal end of our political association. If the power of affording it be placed under the direction of the union, there will be no danger of a supine and listless inattention to the dangers of a neighbour, till its near approach had superadded the incitements of self preservation to the too feeble impulses of duty and sympathy. 23

The [New York] Independent Journal: or, the General Advertiser , January 9, 1788. This essay appeared on January 10 in The [New York] Daily Advertiser , on January 11 in New-York Packet , and on January 12 in The New-York Journal, and Daily Patriotic Register . In the McLean description begins The Federalist: A Collection of Essays, Written in Favour of the New Constitution, As Agreed upon by the Federal Convention, September 17, 1787. In Two Volumes (New York: Printed and Sold by J. and A. McLean, 1788). description ends edition this essay is numbered 29, and in the newspapers it is numbered 35.

1 . For background to this document, see “The Federalist. Introductory Note,” October 27, 1787–May 28, 1788 .

2 . “this” substituted for “the” in McLean description begins The Federalist: A Collection of Essays, Written in Favour of the New Constitution, As Agreed upon by the Federal Convention, September 17, 1787. In Two Volumes (New York: Printed and Sold by J. and A. McLean, 1788). description ends and Hopkins description begins The Federalist On The New Constitution. By Publius. Written in 1788. To Which is Added, Pacificus, on The Proclamation of Neutrality. Written in 1793. Likewise, The Federal Constitution, With All the Amendments. Revised and Corrected. In Two Volumes (New York: Printed and Sold by George F. Hopkins, at Washington’s Head, 1802). description ends .

3 . “of the Convention” omitted in McLean and Hopkins.

4 . In the newspaper, “which from”; “from which” was substituted in McLean and Hopkins.

5 . “same” inserted at this point in McLean and Hopkins.

6 . “to whose” through “committed” omitted in McLean and Hopkins.

7 . “requiring the aid of” substituted for “calling out” in McLean and Hopkins.

8 . “of the” inserted at this point in McLean and Hopkins.

9 . “extraordinary” inserted at this point in McLean and Hopkins.

10 . “conviction” substituted for “judgment” in McLean and Hopkins.

11 . “the” inserted at this point in McLean and Hopkins.

12 . “from this State” omitted in McLean and Hopkins.

13 . “nor” substituted for “or even” in McLean and Hopkins.

14 . “nor even a month” inserted at this point in McLean and Hopkins.

15 . “a million of pounds” substituted for “the whole” through “the States” in McLean and Hopkins.

16 . In the newspaper, “extent”; “size” substituted in McLean and Hopkins.

17 . In the newspaper, “them”; “it” substituted in McLean and Hopkins.

18 . “and” inserted at this point in McLean and Hopkins.

19 . In the newspaper, “concerts”; “conceits” was substituted in McLean and Hopkins.

20 . “at being required” substituted for “by being called upon” in McLean and Hopkins.

21 . “distressing” substituted for “hopeless” in McLean and Hopkins.

22 . “to” omitted in Hopkins.

23 . In the newspaper there was an additional paragraph which reads as follows:

“I have now gone through the examination of such of the powers proposed to be vested in the United States, which may be considered as having an immediate relation to the energy of the government; and have endeavoured to answer the principal objections which have been made to them. I have passed over in silence those minor authorities which are either too inconsiderable to have been thought worthy of the hostilities of the opponents of the Constitution, or of too manifest propriety to admit of controversy. The mass of judiciary power however might have claimed an investigation under this head, had it not been for the consideration that its organization and its extent may be more advantageously considered in connection. This has determined me to refer it to the branch of our enquiries, upon which we shall next enter.”

Index Entries

You are looking at.

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Federalist Papers

By: History.com Editors

Updated: June 22, 2023 | Original: November 9, 2009

The Federalist Papers are a collection of essays written in the 1780s in support of the proposed U.S. Constitution and the strong federal government it advocated. In October 1787, the first in a series of 85 essays arguing for ratification of the Constitution appeared in the Independent Journal , under the pseudonym “Publius.” Addressed to “The People of the State of New York,” the essays were actually written by the statesmen Alexander Hamilton , James Madison and John Jay . They would be published serially from 1787-88 in several New York newspapers. The first 77 essays, including Madison’s famous Federalist 10 and Federalist 51 , appeared in book form in 1788. Titled The Federalist , it has been hailed as one of the most important political documents in U.S. history.

Articles of Confederation

As the first written constitution of the newly independent United States, the Articles of Confederation nominally granted Congress the power to conduct foreign policy, maintain armed forces and coin money.

But in practice, this centralized government body had little authority over the individual states, including no power to levy taxes or regulate commerce, which hampered the new nation’s ability to pay its outstanding debts from the Revolutionary War .

In May 1787, 55 delegates gathered in Philadelphia to address the deficiencies of the Articles of Confederation and the problems that had arisen from this weakened central government.

A New Constitution

The document that emerged from the Constitutional Convention went far beyond amending the Articles, however. Instead, it established an entirely new system, including a robust central government divided into legislative , executive and judicial branches.

As soon as 39 delegates signed the proposed Constitution in September 1787, the document went to the states for ratification, igniting a furious debate between “Federalists,” who favored ratification of the Constitution as written, and “Antifederalists,” who opposed the Constitution and resisted giving stronger powers to the national government.

How Did Magna Carta Influence the U.S. Constitution?

The 13th‑century pact inspired the U.S. Founding Fathers as they wrote the documents that would shape the nation.

The Founding Fathers Feared Political Factions Would Tear the Nation Apart

The Constitution's framers viewed political parties as a necessary evil.

Checks and Balances

Separation of Powers The idea that a just and fair government must divide power between various branches did not originate at the Constitutional Convention, but has deep philosophical and historical roots. In his analysis of the government of Ancient Rome, the Greek statesman and historian Polybius identified it as a “mixed” regime with three branches: […]

The Rise of Publius

In New York, opposition to the Constitution was particularly strong, and ratification was seen as particularly important. Immediately after the document was adopted, Antifederalists began publishing articles in the press criticizing it.

They argued that the document gave Congress excessive powers and that it could lead to the American people losing the hard-won liberties they had fought for and won in the Revolution.

In response to such critiques, the New York lawyer and statesman Alexander Hamilton, who had served as a delegate to the Constitutional Convention, decided to write a comprehensive series of essays defending the Constitution, and promoting its ratification.

Who Wrote the Federalist Papers?

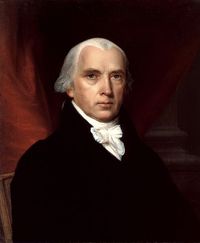

As a collaborator, Hamilton recruited his fellow New Yorker John Jay, who had helped negotiate the treaty ending the war with Britain and served as secretary of foreign affairs under the Articles of Confederation. The two later enlisted the help of James Madison, another delegate to the Constitutional Convention who was in New York at the time serving in the Confederation Congress.

To avoid opening himself and Madison to charges of betraying the Convention’s confidentiality, Hamilton chose the pen name “Publius,” after a general who had helped found the Roman Republic. He wrote the first essay, which appeared in the Independent Journal, on October 27, 1787.

In it, Hamilton argued that the debate facing the nation was not only over ratification of the proposed Constitution, but over the question of “whether societies of men are really capable or not of establishing good government from reflection and choice, or whether they are forever destined to depend for their political constitutions on accident and force.”

After writing the next four essays on the failures of the Articles of Confederation in the realm of foreign affairs, Jay had to drop out of the project due to an attack of rheumatism; he would write only one more essay in the series. Madison wrote a total of 29 essays, while Hamilton wrote a staggering 51.

Federalist Papers Summary

In the Federalist Papers, Hamilton, Jay and Madison argued that the decentralization of power that existed under the Articles of Confederation prevented the new nation from becoming strong enough to compete on the world stage or to quell internal insurrections such as Shays’s Rebellion .

In addition to laying out the many ways in which they believed the Articles of Confederation didn’t work, Hamilton, Jay and Madison used the Federalist essays to explain key provisions of the proposed Constitution, as well as the nature of the republican form of government.

'Federalist 10'

In Federalist 10 , which became the most influential of all the essays, Madison argued against the French political philosopher Montesquieu ’s assertion that true democracy—including Montesquieu’s concept of the separation of powers—was feasible only for small states.

A larger republic, Madison suggested, could more easily balance the competing interests of the different factions or groups (or political parties ) within it. “Extend the sphere, and you take in a greater variety of parties and interests,” he wrote. “[Y]ou make it less probable that a majority of the whole will have a common motive to invade the rights of other citizens[.]”

After emphasizing the central government’s weakness in law enforcement under the Articles of Confederation in Federalist 21-22 , Hamilton dove into a comprehensive defense of the proposed Constitution in the next 14 essays, devoting seven of them to the importance of the government’s power of taxation.

Madison followed with 20 essays devoted to the structure of the new government, including the need for checks and balances between the different powers.

'Federalist 51'

“If men were angels, no government would be necessary,” Madison wrote memorably in Federalist 51 . “If angels were to govern men, neither external nor internal controls on government would be necessary.”

After Jay contributed one more essay on the powers of the Senate , Hamilton concluded the Federalist essays with 21 installments exploring the powers held by the three branches of government—legislative, executive and judiciary.

Impact of the Federalist Papers

Despite their outsized influence in the years to come, and their importance today as touchstones for understanding the Constitution and the founding principles of the U.S. government, the essays published as The Federalist in 1788 saw limited circulation outside of New York at the time they were written. They also fell short of convincing many New York voters, who sent far more Antifederalists than Federalists to the state ratification convention.

Still, in July 1788, a slim majority of New York delegates voted in favor of the Constitution, on the condition that amendments would be added securing certain additional rights. Though Hamilton had opposed this (writing in Federalist 84 that such a bill was unnecessary and could even be harmful) Madison himself would draft the Bill of Rights in 1789, while serving as a representative in the nation’s first Congress.

HISTORY Vault: The American Revolution

Stream American Revolution documentaries and your favorite HISTORY series, commercial-free.

Ron Chernow, Hamilton (Penguin, 2004). Pauline Maier, Ratification: The People Debate the Constitution, 1787-1788 (Simon & Schuster, 2010). “If Men Were Angels: Teaching the Constitution with the Federalist Papers.” Constitutional Rights Foundation . Dan T. Coenen, “Fifteen Curious Facts About the Federalist Papers.” University of Georgia School of Law , April 1, 2007.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

U.S. Constitution.net

Federalist papers’ role in constitution.

The formation of the United States Constitution was a pivotal moment in history, reflecting the deep commitment of the Founding Fathers to create a balanced and enduring system of governance. The Federalist Papers, written by Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay, played a crucial role in advocating for this new framework. These essays provided detailed arguments for a strong central government, checks and balances, and the protection of individual liberties.

Historical Context and Purpose

The Articles of Confederation, though groundbreaking, revealed many weaknesses that hindered the viability of a unified nation. Congress couldn't levy taxes, leading to a financially weak federal government. Each state operated almost independently, making commerce a chaotic affair.

The Constitutional Convention of 1787 was filled with lively debates and differing opinions. Federalists pushed for a strong central government, arguing that the survival of the nation depended on a robust framework that could address common needs and settle disputes among states. Antifederalists worried about losing the hard-won liberties they fought for during the Revolution.

Alexander Hamilton, determined to sway public opinion in favor of the new Constitution, enlisted John Jay and James Madison. The trio adopted the pseudonym "Publius," inspired by a Roman general who helped establish the Roman Republic. The Federalist Papers were born from this alliance, starting with Hamilton's first essay in the Independent Journal on October 27, 1787. The essays were a vigorous defense of the new Constitution, explaining its provisions and benefits.

John Jay contributed five essays focusing on foreign policy and the limitations of the Articles of Confederation before dropping out due to illness. Madison, nicknamed "Father of the Constitution," wrote 29 essays, including the crucial Federalist 10, which tackled the issue of factions and argued that a large republic could better manage diverse interests. Hamilton penned 51 essays, exploring the weaknesses of the Articles, stressing the need for a unified nation capable of defending itself and thriving economically, and arguing for the critical issue of taxation.

The Federalist Papers also explored the concept of checks and balances, emphasizing the careful division of power among three branches of government. Federalist 51, written by Madison, famously said, If men were angels, no government would be necessary, underscoring the need for internal and external controls within the government to prevent abuse of power.

Despite the articulate arguments, the Federalist Papers saw limited circulation outside New York, and many delegates remained unconvinced. Yet, a narrow majority eventually voted for ratification, with a promise of future amendments, leading to the Bill of Rights.

The Federalist Papers' long-term impact is awe-inspiring, serving as key references for understanding the Constitution's intentions and revealing the Founders' intent behind federalism, the separation of powers, and individual liberties. George Washington, though not an essayist, played a subtle yet significant role, believing the Federalist Papers were essential in educating the public about the new government's principles.

The Federalist Papers remain a timeless resource for anyone seeking to understand the foundation of American governance, reflecting a deep commitment to creating a government that balances necessary powers with the protection of individual rights.

Key Arguments in the Federalist Papers

The Federalist Papers laid out several paramount arguments advocating for the newly proposed Constitution, addressing concerns and misconceptions while explaining the necessity of a robust federal framework.

One of the primary assertions was the necessity of a strong central government. The existing Articles of Confederation had created a government too weak to address the challenges facing the new nation. Alexander Hamilton articulated the failures of the Articles of Confederation, such as their inability to enforce laws, regulate commerce, or levy taxes. These deficiencies posed a risk to the nation's stability and its ability to defend itself and maintain economic prosperity.

A recurring theme in the Federalist Papers is the concept of checks and balances within the new government structure. The Founders were acutely aware of the dangers of tyranny, whether from an individual despot or a majority faction. James Madison, in Federalist No. 51, famously encapsulated this necessity with the assertion, If men were angels, no government would be necessary. The Constitution's framework ensured that no single branch of government could consolidate unchecked power.

Madison's Federalist No. 10 elucidated the dangers of factionalism and how an extended republic could mitigate these dangers. Madison argued that factions were inevitable in any society. However, the brilliance of a large republic lay in its ability to dilute factional influences. By expanding the sphere, it became less likely that a single faction could dominate the political landscape. This large republic would offer a greater diversity of parties and interests, making it more challenging for any one group to gain a majority and impose its will on others.

- Federalist No. 10 and No. 51 stand out for their detailed treatment of these principles.

- Federalist No. 10 directly challenges Montesquieu's notion that true democracy could only survive in small states.

- Federalist No. 51 further explored the mechanisms necessary to ensure that the branches of government could effectively check each other, thus protecting individual liberty from the risks of consolidated power.

Hamilton's essays also explored deeply the practical aspects of a functional government. In Federalist No. 23 through No. 25 , he argued for the necessity of a federal army, outlining why a strong central government needed the capability to defend its citizens adequately.

Although these essays were written to influence immediate public opinion towards ratification of the Constitution, their insights possess lasting significance. They form a central reference for legal scholars, judges, and anyone seeking to understand the philosophical underpinnings of American governance.

Judicial Interpretation and the Rule of Law

Federalist No. 78 , written by Alexander Hamilton, holds distinct importance in understanding the judiciary's critical role within the framework of the United States Constitution. This essay examines the imperative of an independent judiciary to safeguard the principles of the Constitution and ensure the rule of law. Hamilton posits that the judiciary must be an "intermediate body between the people and their legislature," tasked with ensuring that the will of the people, as enshrined in the Constitution, prevails over any legislative enactments that conflict with it.

Hamilton argues that the judiciary must possess a distinct form of independence to perform its duty effectively. He emphasizes that judges should hold their offices during good behavior to protect them from external pressures and influence. This tenure would grant them the necessary insulation from political factions and undue influence, allowing them to make decisions based solely on constitutional principles and legal merits. By doing so, the judiciary would act as a guardian of the Constitution, protecting individual rights and preventing the encroachment of tyranny from any branch of government.

One of the fundamental assertions in Federalist No. 78 is the principle of judicial review. Hamilton contends that when laws enacted by the legislature contravene the Constitution, it is the judiciary's duty to declare such laws void. He articulates that the Constitution is the "fundamental law" and asserts that it embodies the will of the people, which transcends ordinary legislative acts. Thus, judges ought to prioritize the Constitution in their rulings, interpreting its provisions faithfully to preserve the rule of law.

Hamilton further stresses the importance of the judiciary in maintaining the balance of power among the three branches of government. He elucidates how the judiciary serves as a check on the other branches, ensuring that neither the executive nor the legislative branches exceed their constitutional authority. By interpreting the Constitution and invalidating unconstitutional laws, the judiciary upholds the principle of checks and balances, which is essential to preserving a functional and fair government.

Federalist No. 78 also touches on the inherent limitations of the judiciary's power. Hamilton recognizes that the judiciary, as the "least dangerous" branch, lacks the force of the executive and the financial control of the legislature. Its power rests solely on judgment and the effective interpretation of laws.

The impact of Hamilton's arguments in Federalist No. 78 reverberates through American judicial history. The principle of judicial review established in Marbury v. Madison (1803) finds its roots in Hamilton's articulation. Chief Justice John Marshall's landmark decision in Marbury v. Madison affirms Hamilton's vision, cementing the judiciary's role as the arbiter of constitutional interpretation. Through this decision, the judiciary asserted its authority to review and nullify laws that contravened the Constitution, thereby ensuring that constitutional principles remain supreme. 1

In the broader context of constitutional interpretation, Federalist No. 78 remains a cornerstone. It underscores the necessity of a judiciary that can interpret the Constitution free from external pressures and biases. The essay's insights continue to guide judicial philosophy, emphasizing the judiciary's role in protecting individual rights and maintaining the rule of law against potential overreach by the legislative or executive branches.

Hamilton's vision in Federalist No. 78 exemplifies the brilliance of the Founding Fathers in crafting a system of governance that preserves liberty while ensuring effective government. His advocacy for an independent judiciary and judicial review demonstrates the depth of thought and foresight that went into the Constitution.

Impact on Ratification and Subsequent Amendments

The influence of the Federalist Papers on the ratification debates, particularly in New York, was significant. New York was a battleground of fierce political contention where Anti-Federalist sentiments were deeply entrenched. Critics of the proposed Constitution feared that it concentrated too much power in the hands of a centralized government, potentially trampling on the liberties won during the American Revolution. 1 The essays by Hamilton, Madison, and Jay—published under the collective pseudonym "Publius"—aimed to counter these arguments, presenting a reasoned case for ratification.

As the essays circulated through New York newspapers, they became the focus of public debates. They served as an educational tool, clarifying the intentions behind various constitutional provisions. Hamilton's essays explained the necessity of federal taxing power and a standing military, addressing concerns over economic stability and national defense. Madison's writings on the separation of powers and the dangers of factionalism provided reassurance that the Constitution was designed to protect individual liberties.

Despite the compelling nature of the Federalist Papers, their initial impact on New York's ratification process was nuanced. The essays did not instantly convert Anti-Federalists but succeeded in shaping the discourse and providing Federalists with a robust framework to defend the new Constitution.

The New York ratifying convention in 1788 was a critical juncture. Anti-Federalists held a majority, and securing ratification seemed an uphill battle. Nonetheless, the arguments put forth by the Federalist Papers played a strategic role. Delegates like Hamilton and Madison used these writings as a foundation to argue their points, underscoring that a stronger federal government was indispensable for unity and stability.

A turning point came with the promise of future amendments. Recognizing the pervasive concerns about individual liberties and potential government overreach, Federalists agreed to support a Bill of Rights as a condition for ratification. 2 This compromise was pivotal, mollifying skeptics by ensuring that the first ten amendments would safeguard fundamental rights.

The persuasive power of the Federalist Papers, combined with the promise of a Bill of Rights, led to a narrow victory for the Federalists in New York. This state's ratification aided in securing the Constitution's broader national acceptance, aligning with the necessary momentum to establish a strong federal framework.

The adoption of the Bill of Rights in 1791 reflected many of the concerns debated during the ratification process. James Madison, recognizing the anxieties articulated by the Anti-Federalists, took the lead in drafting these amendments, addressing fears that the new government might become too powerful and encroach on individual freedoms.

The Federalist Papers significantly impacted the ratification debates by addressing the Anti-Federalists' concerns and paving the way for a balanced approach to governance that included the Bill of Rights. The collaboration and writings of Hamilton, Madison, and Jay have left an indelible mark, ensuring that the Constitution remains a living testament to the principles of liberty and justice.

Enduring Legacy and Modern Relevance

The Federalist Papers have an enduring legacy that continues to shape the understanding and interpretation of the United States Constitution among legal scholars and within American political theory. These essays have become foundational texts within legal analysis, political science, and education, providing a window into the minds of the Founding Fathers and their vision for the republic.

The Federalist Papers maintain their modern relevance through their application in legal contexts. The essays are frequently cited in Supreme Court decisions and legal arguments as authoritative sources that elucidate the Framers' intent. In landmark cases such as Marbury v. Madison and McCulloch v. Maryland , the Supreme Court utilized insights from the Federalist Papers to interpret key constitutional provisions, reinforcing the judiciary's role in checking legislative and executive power.

In Marbury v. Madison , Chief Justice John Marshall drew upon Hamilton's Federalist No. 78 to establish the principle of judicial review, asserting the judiciary's duty to declare unconstitutional laws void. 3 This principle, rooted in Hamilton's argument for the primacy of the Constitution over ordinary legislative acts, underscored the judiciary's role as a guardian of the Constitution.

The arguments laid out in the Federalist Papers continue to inform debates about the balance of power between state and federal governments. Madison's Federalist No. 10 and No. 51 are frequently referenced in discussions about federalism and the separation of powers, providing a theoretical framework that guides contemporary interpretations of federal authority and state sovereignty.

Beyond the legal realm, the Federalist Papers are indispensable in academic circles, particularly in political science and history. They serve as key texts for understanding the philosophical underpinnings of the United States' political system, examining essential concepts such as:

- Republicanism

- Representative democracy

- Safeguards against tyranny

Educational institutions also recognize the value of the Federalist Papers in teaching foundational principles of governance. By studying these essays, students gain insights into the difficulty of building a government that seeks to balance power and liberty—a lesson that remains pertinent in today's political climate.

The Federalist Papers illustrate the timeless struggle to establish a resilient yet adaptable government. The Founders were keenly aware of the challenges of governance, and their reflections in these essays offer enduring wisdom. The need for checks and balances, the threats posed by factions, and the importance of an independent judiciary are principles that continue to resonate, guiding American governance through evolving circumstances.

In contemporary political discourse, the Federalist Papers are often invoked in discussions about originalism and the conservative interpretation of the Constitution . These essays embody a commitment to the original intent of the Framers, serving as a crucial resource for those who advocate for maintaining the Constitution's foundational principles.

The legacy of the Federalist Papers extends well beyond their initial purpose. They remain a vital resource for legal interpretation, academic study, and public understanding of the United States Constitution. The wisdom imparted by Hamilton, Madison, and Jay continues to illuminate the principles of American governance, reinforcing the importance of a balanced and just republic.

The Federalist Papers (1787-1788)

Federalist papers.

After the Constitution was completed during the summer of 1787, the work of ratifying it (or approving it) began. As the Constitution itself required, 3/4ths of the states would have to approve the new Constitution before it would go into effect for those ratifying states.

The Constitution granted the national government more power than under the Articles of Confederation . Many Americans were concerned that the national government with its new powers, as well as the new division of power between the central and state governments, would threaten liberty.

What are the Federalist Papers?

In order to help convince their fellow Americans of their view that the Constitution would not threaten freedom, Federalist Paper authors, James Madison , Alexander Hamilton , and John Jay teamed up in 1788 to write a series of essays in defense of the Constitution. The essays, which appeared in newspapers addressed to the people of the state of New York, are known as the Federalist Papers. They are regarded as one of the most authoritative sources on the meaning of the Constitution, including constitutional principles such as checks and balances, federalism, and separation of powers.

Federalist Papers Collection

Federalist and anti-federalist playlist, related resources.

Would you have been a Federalist or an Anti-Federalist?

Federalist or Anti-Federalist? Over the next few months we will explore through a series of eLessons the debate over ratification of the United States Constitution as discussed in the Federalist and Anti-Federalist papers. We look forward to exploring this important debate with you! One of the great debates in American history was over the ratification […]

Federalist No. 1 Excerpts Annotated

Federalist 10

Written by James Madison, this essay defended the form of republican government proposed by the Constitution. Critics of the Constitution argued that the proposed federal government was too large and would be unresponsive to the people.

Primary Source: Federalist No. 26

Primary Source: Federalist No. 33

Handout E: Excerpts from Federalist No. 39, James Madison (1788)

Primary Source: Excerpts from Federalist No. 44

Handout B: Excerpts from Federalist No 10, 51, 55, and 57

Handout I: Excerpts of Federalist No. 57

Primary Source: Federalist No. 39

Primary Source: Madison – Excerpts from Federalist No. 47 (1788)

Federalist 51

In this Federalist Paper, James Madison explains and defends the checks and balances system in the Constitution. Each branch of government is framed so that its power checks the power of the other two branches; additionally, each branch of government is dependent on the people, who are the source of legitimate authority.

Handout A: Excerpts from Federalist No 62

Primary Source: Excerpts from Federalist No. 63

Federalist 70

In this Federalist Paper, Alexander Hamilton argues for a strong executive leader, as provided for by the Constitution, as opposed to the weak executive under the Articles of Confederation. He asserts, “energy in the executive is the leading character in the definition of good government.

Primary Source: Federalist No. 78 Excerpts Annotated

Primary Source: Federalist No. 84 Excerpts Annotated

The Federalist Papers

The Federalist Papers are a series of 85 essays arguing in support of the United States Constitution . Alexander Hamilton , James Madison , and John Jay were the authors behind the pieces, and the three men wrote collectively under the name of Publius .

Seventy-seven of the essays were published as a series in The Independent Journal , The New York Packet , and The Daily Advertiser between October of 1787 and August 1788. They weren't originally known as the "Federalist Papers," but just "The Federalist." The final 8 were added in after.

At the time of publication, the authorship of the articles was a closely guarded secret. It wasn't until Hamilton's death in 1804 that a list crediting him as one of the authors became public. It claimed fully two-thirds of the essays for Hamilton. Many of these would be disputed by Madison later on, who had actually written a few of the articles attributed to Hamilton.

Once the Federal Convention sent the Constitution to the Confederation Congress in 1787, the document became the target of criticism from its opponents. Hamilton, a firm believer in the Constitution, wrote in Federalist No. 1 that the series would "endeavor to give a satisfactory answer to all the objections which shall have made their appearance, that may seem to have any claim to your attention."

Alexander Hamilton was the force behind the project, and was responsible for recruiting James Madison and John Jay to write with him as Publius. Two others were considered, Gouverneur Morris and William Duer . Morris rejected the offer, and Hamilton didn't like Duer's work. Even still, Duer managed to publish three articles in defense of the Constitution under the name Philo-Publius , or "Friend of Publius."

Hamilton chose "Publius" as the pseudonym under which the series would be written, in honor of the great Roman Publius Valerius Publicola . The original Publius is credited with being instrumental in the founding of the Roman Republic. Hamilton thought he would be again with the founding of the American Republic. He turned out to be right.

John Jay was the author of five of the Federalist Papers. He would later serve as Chief Justice of the United States. Jay became ill after only contributed 4 essays, and was only able to write one more before the end of the project, which explains the large gap in time between them.

Jay's Contributions were Federalist: No. 2 , No. 3 , No. 4 , No. 5 , and No. 64 .

James Madison , Hamilton's major collaborator, later President of the United States and "Father of the Constitution." He wrote 29 of the Federalist Papers, although Madison himself, and many others since then, asserted that he had written more. A known error in Hamilton's list is that he incorrectly ascribed No. 54 to John Jay, when in fact Jay wrote No. 64 , has provided some evidence for Madison's suggestion. Nearly all of the statistical studies show that the disputed papers were written by Madison, but as the writers themselves released no complete list, no one will ever know for sure.

Opposition to the Bill of Rights

The Federalist Papers, specifically Federalist No. 84 , are notable for their opposition to what later became the United States Bill of Rights . Hamilton didn't support the addition of a Bill of Rights because he believed that the Constitution wasn't written to limit the people. It listed the powers of the government and left all that remained to the states and the people. Of course, this sentiment wasn't universal, and the United States not only got a Constitution, but a Bill of Rights too.

No. 1: General Introduction Written by: Alexander Hamilton October 27, 1787

No.2: Concerning Dangers from Foreign Force and Influence Written by: John Jay October 31, 1787

No. 3: The Same Subject Continued: Concerning Dangers from Foreign Force and Influence Written by: John Jay November 3, 1787

No. 4: The Same Subject Continued: Concerning Dangers from Foreign Force and Influence Written by: John Jay November 7, 1787

No. 5: The Same Subject Continued: Concerning Dangers from Foreign Force and Influence Written by: John Jay November 10, 1787

No. 6:Concerning Dangers from Dissensions Between the States Written by: Alexander Hamilton November 14, 1787

No. 7 The Same Subject Continued: Concerning Dangers from Dissensions Between the States Written by: Alexander Hamilton November 15, 1787

No. 8: The Consequences of Hostilities Between the States Written by: Alexander Hamilton November 20, 1787

No. 9 The Union as a Safeguard Against Domestic Faction and Insurrection Written by: Alexander Hamilton November 21, 1787

No. 10 The Same Subject Continued: The Union as a Safeguard Against Domestic Faction and Insurrection Written by: James Madison November 22, 1787

No. 11 The Utility of the Union in Respect to Commercial Relations and a Navy Written by: Alexander Hamilton November 24, 1787

No 12: The Utility of the Union In Respect to Revenue Written by: Alexander Hamilton November 27, 1787

No. 13: Advantage of the Union in Respect to Economy in Government Written by: Alexander Hamilton November 28, 1787

No. 14: Objections to the Proposed Constitution From Extent of Territory Answered Written by: James Madison November 30, 1787

No 15: The Insufficiency of the Present Confederation to Preserve the Union Written by: Alexander Hamilton December 1, 1787

No. 16: The Same Subject Continued: The Insufficiency of the Present Confederation to Preserve the Union Written by: Alexander Hamilton December 4, 1787

No. 17: The Same Subject Continued: The Insufficiency of the Present Confederation to Preserve the Union Written by: Alexander Hamilton December 5, 1787

No. 18: The Same Subject Continued: The Insufficiency of the Present Confederation to Preserve the Union Written by: James Madison December 7, 1787

No. 19: The Same Subject Continued: The Insufficiency of the Present Confederation to Preserve the Union Written by: James Madison December 8, 1787

No. 20: The Same Subject Continued: The Insufficiency of the Present Confederation to Preserve the Union Written by: James Madison December 11, 1787

No. 21: Other Defects of the Present Confederation Written by: Alexander Hamilton December 12, 1787

No. 22: The Same Subject Continued: Other Defects of the Present Confederation Written by: Alexander Hamilton December 14, 1787

No. 23: The Necessity of a Government as Energetic as the One Proposed to the Preservation of the Union Written by: Alexander Hamilton December 18, 1787

No. 24: The Powers Necessary to the Common Defense Further Considered Written by: Alexander Hamilton December 19, 1787

No. 25: The Same Subject Continued: The Powers Necessary to the Common Defense Further Considered Written by: Alexander Hamilton December 21, 1787

No. 26: The Idea of Restraining the Legislative Authority in Regard to the Common Defense Considered Written by: Alexander Hamilton December 22, 1787

No. 27: The Same Subject Continued: The Idea of Restraining the Legislative Authority in Regard to the Common Defense Considered Written by: Alexander Hamilton December 25, 1787

No. 28: The Same Subject Continued: The Idea of Restraining the Legislative Authority in Regard to the Common Defense Considered Written by: Alexander Hamilton December 26, 1787

No. 29: Concerning the Militia Written by: Alexander Hamilton January 9, 1788

No. 30: Concerning the General Power of Taxation Written by: Alexander Hamilton December 28, 1787

No. 31: The Same Subject Continued: Concerning the General Power of Taxation Written by: Alexander Hamilton January 1, 1788

No. 32: The Same Subject Continued: Concerning the General Power of Taxation Written by: Alexander Hamilton January 2, 1788

No. 33: The Same Subject Continued: Concerning the General Power of Taxation Written by: Alexander Hamilton January 2, 1788

No. 34: The Same Subject Continued: Concerning the General Power of Taxation Written by: Alexander Hamilton January 5, 1788

No. 35: The Same Subject Continued: Concerning the General Power of Taxation Written by: Alexander Hamilton January 5, 1788

No. 36: The Same Subject Continued: Concerning the General Power of Taxation Written by: Alexander Hamilton January 8, 1788

No. 37: Concerning the Difficulties of the Convention in Devising a Proper Form of Government Written by: Alexander Hamilton January 11, 1788

No. 38: The Same Subject Continued, and the Incoherence of the Objections to the New Plan Exposed Written by: James Madison January 12, 1788

No. 39: The Conformity of the Plan to Republican Principles Written by: James Madison January 18, 1788

No. 40: The Powers of the Convention to Form a Mixed Government Examined and Sustained Written by: James Madison January 18, 1788

No. 41: General View of the Powers Conferred by the Constitution Written by: James Madison January 19, 1788

No. 42: The Powers Conferred by the Constitution Further Considered Written by: James Madison January 22, 1788

No. 43: The Same Subject Continued: The Powers Conferred by the Constitution Further Considered Written by: James Madison January 23, 1788

No. 44: Restrictions on the Authority of the Several States Written by: James Madison January 25, 1788

No. 45: The Alleged Danger From the Powers of the Union to the State Governments Considered Written by: James Madison January 26, 1788

No. 46: The Influence of the State and Federal Governments Compared Written by: James Madison January 29, 1788

No. 47: The Particular Structure of the New Government and the Distribution of Power Among Its Different Parts Written by: James Madison January 30, 1788

No. 48: These Departments Should Not Be So Far Separated as to Have No Constitutional Control Over Each Other Written by: James Madison February 1, 1788

No. 49: Method of Guarding Against the Encroachments of Any One Department of Government Written by: James Madison February 2, 1788

No. 50: Periodic Appeals to the People Considered Written by: James Madison February 5, 1788

No. 51: The Structure of the Government Must Furnish the Proper Checks and Balances Between the Different Departments Written by: James Madison February 6, 1788

No. 52: The House of Representatives Written by: James Madison February 8, 1788

No. 53: The Same Subject Continued: The House of Representatives Written by: James Madison February 9, 1788

No. 54: The Apportionment of Members Among the States Written by: James Madison February 12, 1788

No. 55: The Total Number of the House of Representatives Written by: James Madison February 13, 1788

No. 56: The Same Subject Continued: The Total Number of the House of Representatives Written by: James Madison February 16, 1788

No. 57: The Alleged Tendency of the New Plan to Elevate the Few at the Expense of the Many Written by: James Madison February 19, 1788

No. 58: Objection That The Number of Members Will Not Be Augmented as the Progress of Population Demands Considered Written by: James Madison February 20, 1788

No. 59: Concerning the Power of Congress to Regulate the Election of Members Written by: Alexander Hamilton February 22, 1788

No. 60: The Same Subject Continued: Concerning the Power of Congress to Regulate the Election of Members Written by: Alexander Hamilton February 23, 1788

No. 61: The Same Subject Continued: Concerning the Power of Congress to Regulate the Election of Members Written by: Alexander Hamilton February 26, 1788

No. 62: The Senate Written by: James Madison February 27, 1788

No. 63: The Senate Continued Written by: James Madison March 1, 1788

No. 64: The Powers of the Senate Written by: John Jay March 5, 1788

No. 65: The Powers of the Senate Continued Written by: Alexander Hamilton March 7, 1788

No. 66: Objections to the Power of the Senate To Set as a Court for Impeachments Further Considered Written by: Alexander Hamilton March 8, 1788

No. 67: The Executive Department Written by: Alexander Hamilton March 11, 1788

No. 68: The Mode of Electing the President Written by: Alexander Hamilton March 12, 1788

No. 69: The Real Character of the Executive Written by: Alexander Hamilton March 14, 1788

No. 70: The Executive Department Further Considered Written by: Alexander Hamilton March 15, 1788

No. 71: The Duration in Office of the Executive Written by: Alexander Hamilton March 18, 1788

No. 72: The Same Subject Continued, and Re-Eligibility of the Executive Considered Written by: Alexander Hamilton March 19, 1788

No. 73: The Provision For The Support of the Executive, and the Veto Power Written by: Alexander Hamilton March 21, 1788

No. 74: The Command of the Military and Naval Forces, and the Pardoning Power of the Executive Written by: Alexander Hamilton March 25, 1788

No. 75: The Treaty Making Power of the Executive Written by: Alexander Hamilton March 26, 1788

No. 76: The Appointing Power of the Executive Written by: Alexander Hamilton April 1, 1788

No. 77: The Appointing Power Continued and Other Powers of the Executive Considered Written by: Alexander Hamilton April 2, 1788

No. 78: The Judiciary Department Written by: Alexander Hamilton June 14, 1788

No. 79: The Judiciary Continued Written by: Alexander Hamilton June 18, 1788

No. 80: The Powers of the Judiciary Written by: Alexander Hamilton June 21, 1788

No. 81: The Judiciary Continued, and the Distribution of the Judicial Authority Written by: Alexander Hamilton June 25, 1788

No. 82: The Judiciary Continued Written by: Alexander Hamilton July 2, 1788

No. 83: The Judiciary Continued in Relation to Trial by Jury Written by: Alexander Hamilton July 5, 1788

No. 84: Certain General and Miscellaneous Objections to the Constitution Considered and Answered Written by: Alexander Hamilton July 16, 1788

No. 85: Concluding Remarks Written by: Alexander Hamilton August 13, 1788

Images courtesy of Wikimedia Commons, licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-Share-Alike License 3.0.

© Oak Hill Publishing Company. All rights reserved. Oak Hill Publishing Company. Box 6473, Naperville, IL 60567 For questions or comments about this site please email us at [email protected]

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Federalist No. 29, titled "Concerning the Militia", is a political essay by Alexander Hamilton and the twenty-ninth of The Federalist Papers. It was first published in Independent Journal on January 9, 1788, under the pseudonym Publius, the name under which all The Federalist Papers were published.

In the McLean description begins The Federalist: A Collection of Essays, Written in Favour of the New Constitution, As Agreed upon by the Federal Convention, September 17, 1787. In Two Volumes (New York: Printed and Sold by J. and A. McLean, 1788). description ends edition this essay is numbered 29, and in the newspapers it is numbered 35.

The Federalist Papers is a collection of 85 articles and essays written by Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay under the collective pseudonym "Publius" to promote the ratification of the Constitution of the United States.

The Federalist, commonly referred to as the Federalist Papers, is a series of 85 essays written by Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, and James Madison between October 1787 and May 1788. The essays were published anonymously, under the pen name "Publius," in various New York state newspapers of the time.

The Federalist Papers are a series of essays written by Alexander Hamilton, James Madison and John Jay supporting the Constitution and a strong federal government.

Study with Quizlet and memorize flashcards containing terms like What were the federalist papers?, Who wrote the Federalists Papers?, How many essays were published in the Federalist papers? and more.

Madison, nicknamed "Father of the Constitution," wrote 29 essays, including the crucial Federalist 10, which tackled the issue of factions and argued that a large republic could better manage diverse interests.

Federalist papers, series of 85 essays on the proposed new Constitution of the United States and on the nature of republican government, published between 1787 and 1788 by Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay in an effort to persuade New York state voters to support ratification.

Federalist Paper authors, James Madison, Alexander Hamilton, and John Jay teamed up in 1788 to write a series of essays in defense of the Constitution. The Federalist Papers were written to help convince Americans that the Constitution would not threaten freedom.

James Madison, Hamilton's major collaborator, later President of the United States and "Father of the Constitution." He wrote 29 of the Federalist Papers, although Madison himself, and many others since then, asserted that he had written more.