Advertisement

Gender Inequality and Gender Gap: An Overview of the Indian Scenario

- Original Article

- Published: 08 November 2023

- Volume 40 , pages 232–254, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

- Issabella Jose ORCID: orcid.org/0009-0003-0966-7063 1 &

- Sunitha Sivaraman ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9976-207X 2

1932 Accesses

2 Citations

Explore all metrics

Gender inequality is pervasive in many societies, creating disparities between genders in terms of what they can accomplish and their access to opportunities. Achieving sustainable development necessitates providing equal chances to all, regardless of gender. Despite the remarkable economic progress India has attained, gender inequality is a major concern. Against this backdrop, the current study endeavours to comprehend gender inequality and analyse the extent of gender gap in India using secondary data. India’s performance in major gender-related indices paints a stark picture of gender inequality in the country. The study also finds that there exists gender gap in India concerning health, education, political representation and economic participation. Further, the study finds that female labour force participation has steadily declined over the years, raising concerns over the inclusiveness of India’s economic growth. The findings of the study provide valuable insights to policymakers to formulate effective policies that promote gender equality.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Gender Inequality: A Comparison of India and USA

Gender Equality Index for Country Regions (GEICR)

An Extended Regional Gender Gaps Index (eRGGI): Comparative Measurement of Gender Equality at Different Levels of Regionality

The United Nations member states adopted the 17 SDGs in 2015 as part of the ‘2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development'. Achieving gender equality and empowering women and girls is the fifth goal of the SDGs.

The Gender Equality Index was developed by EIGE in 2013 to measure the progress of gender equality in the European Union.

The Social Institutions and Gender Index was developed by Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development Centre in 2007 to measure discrimination against women in social institutions.

The Economist Intelligence Unit developed the Women’s Economic Opportunity Index in 2010 to measure the economic opportunities available for women.

Based on the HDI score, countries are classified into different categories: low human development (below 0.550), medium human development (0.550–0.699), high human development (0.700–0.799) and very high human development (above 0.799).

On the basis of Gender Development Index (GDI) scores, countries are divided into five categories according to the degree of deviation from gender parity in Human Development Index (HDI) values. Category 1 represents the countries that are closest to achieving gender parity, while Category 5 represents the countries that are farthest from parity.

A decrease in the GII score indicates that gender inequalities concerning reproductive health, empowerment and the labour market have reduced.

The Population Census of India is carried out decennially, and the most recent census was conducted in 2011. Due to the unprecedented circumstances posed by the COVID-19 pandemic, the 2021 census has been postponed. Hence 2011 census is the latest available evidence.

Patrilocality is the practice wherein the woman resides with her husband’s family post-marriage.

The Indian Parliament is the supreme law-making body in India.

The Panchayati Raj is the local self-government system in the villages in India.

Barro, R. J. (2001). Human capital and growth. American Economic Review, 91 (2), 12–17. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.91.2.12

Article Google Scholar

Batra, R., & Reio, T. G., Jr. (2016). Gender inequality issues in India. Advances in Developing Human Resources, 18 (1), 88–101. https://doi.org/10.1177/1523422316630651

Bhalla, S., & Kaur, R. (2011). Labour force participation of women in India: Some facts . Some queries, LSE Asia research centre working paper, 40.

Blumberg, R. L. (2005). Women’s economic empowerment as the magic potion of development. In 100th annual meeting of the American Sociological Association, August, Philadelphia.

Census Report of India. (Various years). Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India.

Chaudhary, R., & Verick, S. (2014). Female labour force participation in India and beyond . ILO Asia- Pacific working paper series, New Delhi.

Esteve-Volart, B. (2004). Gender discrimination and growth: Theory and evidence from India . LSE STICERD research paper no. DEDPS42.

European Institute for Gender Equality. (2016). Glossary and thesaurus. https://eige.europa.eu/thesaurus/overview

Gangopadhyay, J., & Ghosal, R. K. (2017). Gender inequality in Indian states-development of a gender discrimination index. Business Studies, 26 , 1–12.

Google Scholar

George, N., Britto, R., Abhinaya, R., Archana, M., Aruna, A. S., & Narayan, M. A. (2021). Child sex ratio-declining trend: Reasons and consequences. Indian Journal of Child Health, 8 (10), 349–351.

Ghoshal, R., & Dhar, A. (2012). Child sex ratio and the politics of ‘enemisation.’ Economic and Political Weekly, 47 (49), 20–22.

Human Development Report. (Various years). United Nations Development Programme.

Jayachandran, S. (2015). The roots of gender inequality in developing countries. Annual Review of Economics, 7 (1), 63–88. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-economics-080614-115404

Kabeer, N. (2005). Gender equality and women’s empowerment: A critical analysis of the third millennium development goal 1. Gender and Development, 13 (1), 13–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/13552070512331332273

Klasen, S. (1999). Does gender inequality reduce growth and development? Evidence from cross-country regressions . Policy Research Report on Gender and Development, World Bank.

Kulkarni, P. M. (2020). Sex ratio at birth in India: Recent trends and patterns . United Nations Population Fund-India.

Mahanta, B., & Nayak, P. (2013). Gender inequality in north east India. PCC Journal of Economics and Commerce, 7 , 1–13. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2202044

National Family Health Survey Report. (Various years). Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India.

National Statistical Office. (2020). India—Household social consumption: Education, NSS 75th round schedule-25.2:July 2017–June 2018 . http://14.139.60.153/handle/123456789/13670

Okojie, C. E. (1994). Gender inequalities of health in the third world. Social Science and Medicine, 39 (9), 1237–1247. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(94)90356-5

Permanyer, I. (2010). The measurement of multidimensional gender inequality: Continuing the debate. Social Indicators Research, 95 , 181–198. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-009-9463-4

Press Information Bureau. (2021). Initiatives by Government for reducing Gender Gap in all aspects of Social, Economic and Political Life . Retrieved 7 February 2023 from https://pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=1707475

Prillaman, S. A. (2021). Strength in numbers: How women’s groups close India’s political gender gap. American Journal of Political Science, 67 (2), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12651

Rammohan, A., & Vu, P. (2018). Gender inequality in education and kinship norms in India. Feminist Economics, 24 (1), 142–167. https://doi.org/10.1080/13545701.2017.1364399

Razvi M., Roth G. (2004). Socio-economic development and gender inequality in India. In Proceedings of the academy of human resource development, academy of human resource development, Bowling Green, Ohio .

Rustagi, P. (2004). Significance of gender-related development indicators: An analysis of Indian states. Indian Journal of Gender Studies, 11 (3), 291–343. https://doi.org/10.1177/097152150401100303

Sen, G., & Östlin, P. (2008). Gender inequity in health: Why it exists and how we can change it. Global Public Health, 3 (1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441690801900795

Smith, E., Kemmis, R. B., & Comyn, P. (2014). How can the expansion of the apprenticeship system in India create conditions for greater equity and social justice. Australian Journal of Adult Learning, 54 (3), 368–388.

Sundaram, A., & Vanneman, R. (2008). Gender differentials in literacy in India: The intriguing relationship with women’s labour force participation. World Development, 36 (1), 128–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2007.02.017

The Global Gender Gap Report. (Various years). World Economic Forum.

Thomas, R. E. (2013). Gender inequality in modern India–scenario and solutions. IOSR Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 13 (3), 48–50.

Thomas, V. P. (2020). Sex-selective abortions: The prevalence in India and its ramifications on sex trafficking. The Compass, 1 (7), 21–27.

Tisdell, C. A. (2021). How has India’s economic growth and development affected its gender inequality? Journal of the Asia Pacific Economy, 26 (2), 209–229. https://doi.org/10.1080/13547860.2021.1917093

Tiwari, A. K. (2013). Gender inequality in terms of health and nutrition in India: Evidence from national family health survey-3. Pacific Business Review International, 5 (1), 24–34.

UNDP (United Nations Development Programme). (2022). Human Development Report 2021–22: Uncertain times, unsettled lives: Shaping our future in a transforming world . New York. Retrieved 31 January 2023 from https://hdr.undp.org/system/files/documents/global-report-document/hdr2021-22pdf_1.pdf

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization [UNESCO]. (2013). UIS methodology for estimation of mean years of schooling . UNESCO Institute for Statistics. Retrieved 1 March 2023 from http://uis.unesco.org/sites/default/files/documents/uis-methodology-for-estimation-of-mean-years-of-schooling-2013-en_0.pdf

United Nations Environment Programme. (2017). Closing gender gaps essential to sustainable development. Retrieved 1 January 2023 from https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/story/closing-gender-gaps-essential-sustainable-development

United Nations Population Division. (2020). Population division [Dataset: Sex Ratio]. Retrieved 31 January 2023 from https://population.un.org/dataportal/data/indicators/72/locations/356,900/start/2019/end/2022/table/pivotbylocation

Warade, Y., Balsarkar, G., & Bandekar, P. (2014). A study to review sex ratio at birth and analyse preferences for the sex of the unborn. The Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology of India, 64 (1), 23–26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13224-013-0473-4

Waseem, M. (2015). Gender inequalities in education in India: Issues and challenges. International Journal of Research in Commerce and Management, 6 (2), 68–76.

WEF (World Economic Forum). (2017). What is the gender gap (and why is it getting wider)? Retrieved 11 January 2023 from https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2017/11/the-gender-gap-actually-got-worse-in-2017/

WEF (World Economic Forum). (2020). Global gender gap report 2020 . Retrieved 31 January 2023 from https://www.weforum.org/reports/global-gender-gap-report-2021/

WEF (World Economic Forum). (2021). Global gender gap report 2021 . Retrieved 31 January 2023 from https://www.weforum.org/reports/global-gender-gap-report-2021/

WEF (World Economic Forum). (2022a). Global gender gap report 2022 . Retrieved 31 January 2023 from https://www.weforum.org/reports/global-gender-gap-report-2022/

WEF (World Economic Forum). (2022b). This chart shows the growth of India's economy. Retrieved 1 March 2023 from https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2022/09/india-uk-fifth-largest-economy-world#:~:text=India's%20economy%20is%20forecast%20to,th%20highest%20GDP%20by%202027 .

World Bank. (2020a). Gender statistics [Dataset: Life Expectancy at birth]. Retrieved 31 January 2023 from https://databank.worldbank.org/source/gender-statistics

World Bank. (2020b). Gender statistics [Dataset: Mortality Rate]. Retrieved 31 January 2023 from https://databank.worldbank.org/source/gender-statistics

World Bank. (2021). Gender Statistics [Dataset: Labour force participation rate]. Retrieved 31 January 2023 from https://databank.worldbank.org/source/gender-statistics

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Management Studies, National Institute of Technology Calicut, Kozhikode, 673601, Kerala, India

Issabella Jose

Sunitha Sivaraman

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Sunitha Sivaraman .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Jose, I., Sivaraman, S. Gender Inequality and Gender Gap: An Overview of the Indian Scenario. Gend. Issues 40 , 232–254 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12147-023-09313-5

Download citation

Accepted : 24 October 2023

Published : 08 November 2023

Issue Date : December 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s12147-023-09313-5

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

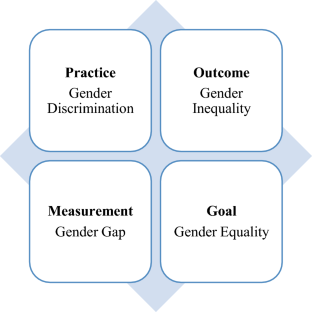

- Gender inequality

- Gender discrimination

- Gender equality

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Chronicle Conversations

- Article archives

- Issue archives

- Join our mailing list

Gender Disparity in Primary Education: The Experience in India

About the author, sushrut desai.

The primary education system in India suffers from numerous shortcomings, not the least being a dire lack of the financial resources required to set up a nationwide network of schools. Traditionally, the sector has been characterized by poor infrastructure, underpaid teaching staff, disillusioned parents and an unmotivated student population. In light of India's commitment to the Millennium Development Goal (MDG) of universal primary education, its major challenge is gender disparity -- and the resulting financial and societal blocks that prevent access of girls to primary education. In a society as deeply stratified as India, disparities in education can be observed through various distributions, such as caste, religion and gender, among others. It is interesting, however, that even within such disadvantaged communities, a consistent feature is widespread gender disparity in educational attainment. For scheduled caste and scheduled tribe girls, the gender gap in education is almost 30 per cent at the primary level and 26 per cent at the upper primary stage. In India's most depressed regions, the probability of girls getting primary education is about 42 per cent lower than boys, and it remains so even when other variables, such as religion and caste, are controlled. It will take a bold and creative policy to bridge this gap. Acknowledging this, the Indian Government has made female education a priority. Its flagship programme for the achievement of universal primary education -- Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan (SSA) or "Education for All" -- places special emphasis on female education and the achievement of gender parity. The question remains, of course, whether this can be attained before the MDGs deadline in 2015. Addressing social problems in a financial context. Societal blocks to female education must be understood as part of a much larger social fabric, which has spawned numerous institutions of gender inequality. Traditionally, a boy's education has been seen as an investment, increasing the earnings and social status of the family; however, different standards apply for girls. The benefits of a girl's education are generally seen as going to the family she marries into, thus providing little incentive to invest scarce resources, both human and monetary, into such activity. Also, given the relatively low educational attainment, especially in rural areas, the marriageability of an educated girl presents its own problems. These factors combine to cement attitudes inherently opposed to female education. However, these attitudes vary widely, even within India, dividing it into two broad groups, with the southern and western states being far ahead in education than the northern and eastern states.* It may be observed that those with the strongest anti-female bias include rich states, such as Punjab and Haryana, as well as poor ones, such as Bihar and Uttar Pradesh. While it would be incorrect to conclude that financial factors play no role in securing educational access, it is safe to say that they are by no means a conclusive indicator of any likelihood of gender parity. Had the problem been solely a financial one, there should have been a steady growth in primary education levels with the 86th Amendment Act of 2002, promising free and compulsory primary education to all children, and the ever-increasing budgetary allocations for primary education that followed. Yet the figures refuse to climb as rapidly as studies projected, even though the financial problems were addressed. This is perhaps because the societal blocks to achieving the goal were underestimated. A study by the World Institute for Development Economics Research (WIDER) at the United Nations University noted that though greater financial capacity in the family had a significantly positive effect on attendance for both genders, it affected girls' education rates almost twice as much as that of boys. Given slightly more comfortable financial conditions, the rate of change in the number of girls getting education almost doubled in comparison to the rate for boys. Financial constraints appear to be a significant disincentive for girls' education in particular. It is difficult to dispute that girls' education occupies a significantly lower social, as well as financial, preference than boys' education. Government response. The Indian Government has not been unresponsive to such findings. The promise of free and compulsory education has been earnestly pursued. It is worthwhile to study the general aspects of SSA before addressing its specific programmes for tackling gender disparity. SSA has adopted a two-pronged approach: to centrally define targets and norms, ensuring uniformity of quality and growth across the country; and to establish an extensive network of local management and bottom-up planning schemes, with the assistance of community groups and non-governmental organizations. Before commencing a fresh project, every state is required to conduct a census to determine the number, age and gender of children in the area. The information is used to draw annual work plans, which are filed with the Central Government, maintaining accountability for funds allocated and used. In a salutary move, states have been obligated to maintain the 1999 levels of real value spending on primary education and to match growing government funding to these areas. This ensures that the financial commitment to education is maintained and increments in budgetary allocations trickle down to the ultimate beneficiaries. SSA places special emphasis on female education. Government initiatives in this regard can be divided into two loose categories: a programme to create "pull factors" to enhance access and retention of girls in schools; and another to create "push factors" to foster in society the conditions necessary to guarantee girls' education. Today, free textbooks are provided to all girls in school up to eighth grade, and back-to-school camps and bridge courses are organized for older girls. However, it is not sufficient to make girls' education more affordable; it also must be made more important as a social preference. We can see numerous examples of schemes to do just that -- schemes which qualitatively alter the very environment of education and challenge the very attitudes that restrict educational access. Government schemes now provide for early childhood care centres in or near schools to free girls from the burden of sibling-care responsibilities. Teacher sensitization programmes are run to promote equitable learning opportunities. Steps are being taken to ensure recruitment of at least 50-per-cent female teaching staff. Local government schemes are attempting to enhance the role of women, especially mothers, in school committees and school-related activities. Additionally, specific schemes have been introduced in depressed areas, focusing on girls from disadvantaged sections of society, predominantly those belonging to scheduled castes, scheduled tribes and religious minorities. Under these schemes, more than 30,000 schools have been developed. In 2006-2007, bridge courses provided education to over 100,000 girls, while the remedial education programmes reached out to over 2 million girls. The depressed north and west states are also showing very promising indicators with innovative programmes, such as that of Haryana state, which provides free bicycles to girls joining sixth grade, or Uttar Pradesh's enthusiastic campaign to mobilize local communities around school-related sports and cultural programmes. While still far from providing education to all, these trends are evidence that the tide is turning. Already, eight states have reported achieving gender parity at the primary level. Enabling conditions are being created, and India is moving perceptibly towards a more girl-friendly educational environment. Criticism. Critics point out that despite its many achievements, qualitative deficiencies in the SSA system abound. The most serious of these is that SSA guidelines are very lenient on school certification standards. Any individual who has completed secondary education can start a school. Few qualitative stipulations are prescribed. While this bolsters statistics, it fails in its true objective. The reality is that children in such schools do not get educated at all. Student and teacher absenteeism, high repetition and dropout rates, and low student performance only worsen the problem. The United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), the Government's partner in SSA, also cites quality of education as India's greatest challenge. Stricter school certification requirements and greater local involvement in teaching and management are therefore absolutely essential to the success of SSA. Trends in India suggest that the country will meet the MDG for universal enrolment. However, WIDER research warns that unless conditions change, India will fail to achieve universal retention as soon as 2015. While India is committed to a qualitative assurance, it is difficult to see high-quality education being provided in the current situation. It would be wrong, however, to end on a note of pessimism. India's achievements in this sector are nothing short of revolutionary. With the number of 6- to 14-year old children rising from 35 million in 1991 to 205 million in 2001, achieving MDG 2 is an uphill task, but one that the Government has met head on. SSA has put India firmly on the path of universal education and gender parity, and there is no looking back.

The UN Chronicle is not an official record. It is privileged to host senior United Nations officials as well as distinguished contributors from outside the United Nations system whose views are not necessarily those of the United Nations. Similarly, the boundaries and names shown, and the designations used, in maps or articles do not necessarily imply endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations.

Safeguarding Human Rights and Information Integrity in the Age of Generative AI

Together, we can ensure that generative AI is used appropriately, and that its benefits are achieved without endangering information integrity and human rights.

The United Nations in a World of Rising Global Challenges

The direction of the work of the United Nations in the coming months and years will focus on how our institution can better address peace and security, sustainable development and human rights for all, including future generations.

How Critical Energy Transition Minerals Can Pave the Way for Shared Prosperity

Now is the time to leverage critical energy transition minerals to update the international trade regime, promote structural diversification and turn the tide of commodity dependence once and for all.

Documents and publications

- Yearbook of the United Nations

- Basic Facts About the United Nations

- Journal of the United Nations

- Meetings Coverage and Press Releases

- United Nations Official Document System (ODS)

- Africa Renewal

Libraries and Archives

- Dag Hammarskjöld Library

- UN Audiovisual Library

- UN Archives and Records Management

- Audiovisual Library of International Law

- UN iLibrary

News and media

- UN News Centre

- UN Chronicle on Twitter

- UN Chronicle on Facebook

The UN at Work

- 17 Goals to Transform Our World

- Official observances

- United Nations Academic Impact (UNAI)

- Protecting Human Rights

- Maintaining International Peace and Security

- The Office of the Secretary-General’s Envoy on Youth

- United Nations Careers

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

studies on the gender disparity in education in India, as well as widespread recogni- tion that son preference leads to gender discrimination, none have examined the role of context in shaping the persistent educational disparity between boys and girls.

Gender discrimination is more frequent among the ethnic minorities in the domain of education. This study among the Muslims in India shows that the Muslims always lag behind the Hindus in literacy rate and there is widening gap between literacy rates of men and women.

trends in gender discrimination across the schooling career of children and found that transition probabilities of girls increased, relative to those of boys, at higher levels of education.

We use a nationally representative longitudinal data set from India to analyze the extent and determinants of gender gap in higher secondary stream choice.

There is considerable evidence of gender disparity in education in India—girls have historically lagged behind boys in educational attainments (Aggarwal 1987; Agrawal and Aggarwal 1994). Further, studies have shown that girls perform much worse than boys in certain regions.

Caste-based discrimination has been widely studied by several social science scholars in the context of Indian higher education. The empirical studies reveal different aspects to the existing discriminatory practices from the teachers, peers and administration in elite educational institutions.

Starovoytova and Namango found that female engineering students experienced gender-based discrimination, while Arora observed students who have migrated to Delhi, the capital of India, from other parts of the country encountered discrimination based on race, gender, and caste.

A low female literacy rate, low mean years of schooling for women and a lower proportion of women with secondary education reflect the existence of gender-based discrimination in educational attainment in India.

Multi-level analyses of data on 18,519 families with opposite sex children from NFHS-3 are used to test the impact of maternal son preference and context on the gender differential in education in India. The results show that girls are at a greater educational disadvantage compared to their brothers in families with maternal son preference.

In light of India's commitment to the Millennium Development Goal (MDG) of universal primary education, its major challenge is gender disparity -- and the resulting financial and societal...