- Privacy Policy

Home » Experimental Design – Types, Methods, Guide

Experimental Design – Types, Methods, Guide

Table of Contents

Experimental design is a structured approach used to conduct scientific experiments. It enables researchers to explore cause-and-effect relationships by controlling variables and testing hypotheses. This guide explores the types of experimental designs, common methods, and best practices for planning and conducting experiments.

Experimental Design

Experimental design refers to the process of planning a study to test a hypothesis, where variables are manipulated to observe their effects on outcomes. By carefully controlling conditions, researchers can determine whether specific factors cause changes in a dependent variable.

Key Characteristics of Experimental Design :

- Manipulation of Variables : The researcher intentionally changes one or more independent variables.

- Control of Extraneous Factors : Other variables are kept constant to avoid interference.

- Randomization : Subjects are often randomly assigned to groups to reduce bias.

- Replication : Repeating the experiment or having multiple subjects helps verify results.

Purpose of Experimental Design

The primary purpose of experimental design is to establish causal relationships by controlling for extraneous factors and reducing bias. Experimental designs help:

- Test Hypotheses : Determine if there is a significant effect of independent variables on dependent variables.

- Control Confounding Variables : Minimize the impact of variables that could distort results.

- Generate Reproducible Results : Provide a structured approach that allows other researchers to replicate findings.

Types of Experimental Designs

Experimental designs can vary based on the number of variables, the assignment of participants, and the purpose of the experiment. Here are some common types:

1. Pre-Experimental Designs

These designs are exploratory and lack random assignment, often used when strict control is not feasible. They provide initial insights but are less rigorous in establishing causality.

- Example : A training program is provided, and participants’ knowledge is tested afterward, without a pretest.

- Example : A group is tested on reading skills, receives instruction, and is tested again to measure improvement.

2. True Experimental Designs

True experiments involve random assignment of participants to control or experimental groups, providing high levels of control over variables.

- Example : A new drug’s efficacy is tested with patients randomly assigned to receive the drug or a placebo.

- Example : Two groups are observed after one group receives a treatment, and the other receives no intervention.

3. Quasi-Experimental Designs

Quasi-experiments lack random assignment but still aim to determine causality by comparing groups or time periods. They are often used when randomization isn’t possible, such as in natural or field experiments.

- Example : Schools receive different curriculums, and students’ test scores are compared before and after implementation.

- Example : Traffic accident rates are recorded for a city before and after a new speed limit is enforced.

4. Factorial Designs

Factorial designs test the effects of multiple independent variables simultaneously. This design is useful for studying the interactions between variables.

- Example : Studying how caffeine (variable 1) and sleep deprivation (variable 2) affect memory performance.

- Example : An experiment studying the impact of age, gender, and education level on technology usage.

5. Repeated Measures Design

In repeated measures designs, the same participants are exposed to different conditions or treatments. This design is valuable for studying changes within subjects over time.

- Example : Measuring reaction time in participants before, during, and after caffeine consumption.

- Example : Testing two medications, with each participant receiving both but in a different sequence.

Methods for Implementing Experimental Designs

- Purpose : Ensures each participant has an equal chance of being assigned to any group, reducing selection bias.

- Method : Use random number generators or assignment software to allocate participants randomly.

- Purpose : Prevents participants or researchers from knowing which group (experimental or control) participants belong to, reducing bias.

- Method : Implement single-blind (participants unaware) or double-blind (both participants and researchers unaware) procedures.

- Purpose : Provides a baseline for comparison, showing what would happen without the intervention.

- Method : Include a group that does not receive the treatment but otherwise undergoes the same conditions.

- Purpose : Controls for order effects in repeated measures designs by varying the order of treatments.

- Method : Assign different sequences to participants, ensuring that each condition appears equally across orders.

- Purpose : Ensures reliability by repeating the experiment or including multiple participants within groups.

- Method : Increase sample size or repeat studies with different samples or in different settings.

Steps to Conduct an Experimental Design

- Clearly state what you intend to discover or prove through the experiment. A strong hypothesis guides the experiment’s design and variable selection.

- Independent Variable (IV) : The factor manipulated by the researcher (e.g., amount of sleep).

- Dependent Variable (DV) : The outcome measured (e.g., reaction time).

- Control Variables : Factors kept constant to prevent interference with results (e.g., time of day for testing).

- Choose a design type that aligns with your research question, hypothesis, and available resources. For example, an RCT for a medical study or a factorial design for complex interactions.

- Randomly assign participants to experimental or control groups. Ensure control groups are similar to experimental groups in all respects except for the treatment received.

- Randomize the assignment and, if possible, apply blinding to minimize potential bias.

- Follow a consistent procedure for each group, collecting data systematically. Record observations and manage any unexpected events or variables that may arise.

- Use appropriate statistical methods to test for significant differences between groups, such as t-tests, ANOVA, or regression analysis.

- Determine whether the results support your hypothesis and analyze any trends, patterns, or unexpected findings. Discuss possible limitations and implications of your results.

Examples of Experimental Design in Research

- Medicine : Testing a new drug’s effectiveness through a randomized controlled trial, where one group receives the drug and another receives a placebo.

- Psychology : Studying the effect of sleep deprivation on memory using a within-subject design, where participants are tested with different sleep conditions.

- Education : Comparing teaching methods in a quasi-experimental design by measuring students’ performance before and after implementing a new curriculum.

- Marketing : Using a factorial design to examine the effects of advertisement type and frequency on consumer purchase behavior.

- Environmental Science : Testing the impact of a pollution reduction policy through a time series design, recording pollution levels before and after implementation.

Experimental design is fundamental to conducting rigorous and reliable research, offering a systematic approach to exploring causal relationships. With various types of designs and methods, researchers can choose the most appropriate setup to answer their research questions effectively. By applying best practices, controlling variables, and selecting suitable statistical methods, experimental design supports meaningful insights across scientific, medical, and social research fields.

- Campbell, D. T., & Stanley, J. C. (1963). Experimental and Quasi-Experimental Designs for Research . Houghton Mifflin Company.

- Shadish, W. R., Cook, T. D., & Campbell, D. T. (2002). Experimental and Quasi-Experimental Designs for Generalized Causal Inference . Houghton Mifflin.

- Fisher, R. A. (1935). The Design of Experiments . Oliver and Boyd.

- Field, A. (2013). Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics . Sage Publications.

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences . Routledge.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Explanatory Research – Types, Methods, Guide

Research Methods – Types, Examples and Guide

Qualitative Research – Methods, Analysis Types...

Focus Groups – Steps, Examples and Guide

Correlational Research – Methods, Types and...

Questionnaire – Definition, Types, and Examples

- Foundations

- Write Paper

Search form

- Experiments

- Anthropology

- Self-Esteem

- Social Anxiety

- Experiments >

Conducting an Experiment

Science revolves around experiments, and learning the best way of conducting an experiment is crucial to obtaining useful and valid results.

This article is a part of the guide:

- Experimental Research

- Pretest-Posttest

- Third Variable

- Research Bias

- Independent Variable

Browse Full Outline

- 1 Experimental Research

- 2.1 Independent Variable

- 2.2 Dependent Variable

- 2.3 Controlled Variables

- 2.4 Third Variable

- 3.1 Control Group

- 3.2 Research Bias

- 3.3.1 Placebo Effect

- 3.3.2 Double Blind Method

- 4.1 Randomized Controlled Trials

- 4.2 Pretest-Posttest

- 4.3 Solomon Four Group

- 4.4 Between Subjects

- 4.5 Within Subject

- 4.6 Repeated Measures

- 4.7 Counterbalanced Measures

- 4.8 Matched Subjects

When scientists speak of experiments, in the strictest sense of the word, they mean a true experiment , where the scientist controls all of the factors and conditions.

Real world observations, and case studies , should be referred to as observational research , rather than experiments.

For example, observing animals in the wild is not a true experiment, because it does not isolate and manipulate an independent variable .

The Basis of Conducting an Experiment

With an experiment, the researcher is trying to learn something new about the world, an explanation of 'why' something happens.

The experiment must maintain internal and external validity, or the results will be useless.

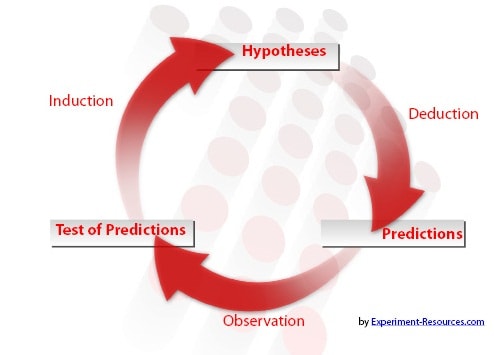

When designing an experiment , a researcher must follow all of the steps of the scientific method , from making sure that the hypothesis is valid and testable , to using controls and statistical tests.

Whilst all scientists use reasoning , operationalization and the steps of the scientific process , it is not always a conscious process.

Experience and practice mean that many scientists follow an instinctive process of conducting an experiment, the 'streamlined' scientific process . Following the basic steps will usually generate valid results, but where experiments are complex and expensive, it is always advisable to follow the rigorous scientific protocols. Conducting an experiment has a number of stages, where the parameters and structure of the experiment are made clear.

Whilst it is rarely practical to follow each step strictly, any aberrations must be justified, whether they arise because of budget, impracticality or ethics .

After deciding upon a hypothesis , and making predictions, the first stage of conducting an experiment is to specify the sample groups. These should be large enough to give a statistically viable study, but small enough to be practical.

Ideally, groups should be selected at random , from a wide selection of the sample population. This allows results to be generalized to the population as a whole.

In the physical sciences, this is fairly easy, but the biological and behavioral sciences are often limited by other factors.

For example, medical trials often cannot find random groups. Such research often relies upon volunteers, so it is difficult to apply any realistic randomization . This is not a problem, as long as the process is justified, and the results are not applied to the population as a whole.

If a psychological researcher used volunteers who were male students, aged between 18 and 24, the findings can only be generalized to that specific demographic group within society.

The sample groups should be divided, into a control group and a test group, to reduce the possibility of confounding variables .

This, again, should be random, and the assigning of subjects to groups should be blind or double blind . This will reduce the chances of experimental error , or bias, when conducting an experiment.

Ethics are often a barrier to this process, because deliberately withholding treatment, as with the Tuskegee study , is not permitted.

Again, any deviations from this process must be explained in the conclusion. There is nothing wrong with compromising upon randomness, where necessary, as long as other scientists are aware of how, and why, the researcher selected groups on that basis.

Stage Three

This stage of conducting an experiment involves determining the time scale and frequency of sampling , to fit the type of experiment.

For example, researchers studying the effectiveness of a cure for colds would take frequent samples, over a period of days. Researchers testing a cure for Parkinson's disease would use less frequent tests, over a period of months or years.

The penultimate stage of the experiment involves performing the experiment according to the methods stipulated during the design phase.

The independent variable is manipulated, generating a usable data set for the dependent variable .

The raw data from the results should be gathered, and analyzed, by statistical means. This allows the researcher to establish if there is any relationship between the variables and accept, or reject, the null hypothesis .

These steps are essential to providing excellent results. Whilst many researchers do not want to become involved in the exact processes of inductive reasoning , deductive reasoning and operationalization , they all follow the basic steps of conducting an experiment. This ensures that their results are valid .

Preparing a Coordination Schema of the Whole Research Plan

Preparing a coordination schema of the research plan may be another useful tool in undertaking research planning. While preparing a coordination schema, one may have to identify the broad variable in the form of parameters, complex variables and disaggregate those in the form of simple variables. Coordination Schema: A Methodological Tool in Research Planning by Purnima Mohapatra is a very useful tool. Arranging everything in a schema not only makes the research more organised, it also saves a lot of valuable time for the researcher.

- Psychology 101

- Flags and Countries

- Capitals and Countries

Martyn Shuttleworth (May 24, 2008). Conducting an Experiment. Retrieved Nov 22, 2024 from Explorable.com: https://explorable.com/conducting-an-experiment

You Are Allowed To Copy The Text

The text in this article is licensed under the Creative Commons-License Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) .

This means you're free to copy, share and adapt any parts (or all) of the text in the article, as long as you give appropriate credit and provide a link/reference to this page.

That is it. You don't need our permission to copy the article; just include a link/reference back to this page. You can use it freely (with some kind of link), and we're also okay with people reprinting in publications like books, blogs, newsletters, course-material, papers, wikipedia and presentations (with clear attribution).

Related articles

Design of Experiment

Social Psychology Experiments

How to Conduct Science Experiments

True Experimental Design

Want to stay up to date? Follow us!

Get all these articles in 1 guide.

Want the full version to study at home, take to school or just scribble on?

Whether you are an academic novice, or you simply want to brush up your skills, this book will take your academic writing skills to the next level.

Download electronic versions: - Epub for mobiles and tablets - For Kindle here - For iBooks here - PDF version here

Save this course for later

Don't have time for it all now? No problem, save it as a course and come back to it later.

Footer bottom

- Privacy Policy

- Subscribe to our RSS Feed

- Like us on Facebook

- Follow us on Twitter

IMAGES