Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Perspective

- Published: 08 March 2022

An applied environmental justice framework for exposure science

- Yoshira Ornelas Van Horne 1 na1 ,

- Cecilia S. Alcala 2 na1 ,

- Richard E. Peltier 3 ,

- Penelope J. E. Quintana 4 ,

- Edmund Seto 5 ,

- Melissa Gonzales 6 ,

- Jill E. Johnston 1 ,

- Lupita D. Montoya 7 ,

- Lesliam Quirós-Alcalá 8 na2 &

- Paloma I. Beamer 9 na2

Journal of Exposure Science & Environmental Epidemiology volume 33 , pages 1–11 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

18k Accesses

55 Citations

83 Altmetric

Metrics details

On the 30th anniversary of the Principles of Environmental Justice established at the First National People of Color Environmental Leadership Summit in 1991 (Principles of Environmental Justice), we continue to call for these principles to be more widely adopted. We propose an environmental justice framework for exposure science to be implemented by all researchers. This framework should be the standard and not an afterthought or trend dismissed by those who believe that science should not be politicized. Most notably, this framework should be centered on the community it seeks to serve. Researchers should meet with community members and stakeholders to learn more about the community, involve them in the research process, collectively determine the environmental exposure issues of highest concern for the community, and develop sustainable interventions and implementation strategies to address them. Incorporating community “funds of knowledge” will also inform the study design by incorporating the knowledge about the issue that community members have based on their lived experiences. Institutional and funding agency funds should also be directed to supporting community needs both during the “active” research phase and at the conclusion of the research, such as mechanisms for dissemination, capacity building, and engagement with policymakers. This multidirectional framework for exposure science will increase the sustainability of the research and its impact for long-term success.

Similar content being viewed by others

Environmental public health research at the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: A blueprint for exposure science in a connected world

Qualitative and mixed methods: informing and enhancing exposure science

Quantifying and addressing the prevalence and bias of study designs in the environmental and social sciences

Introduction.

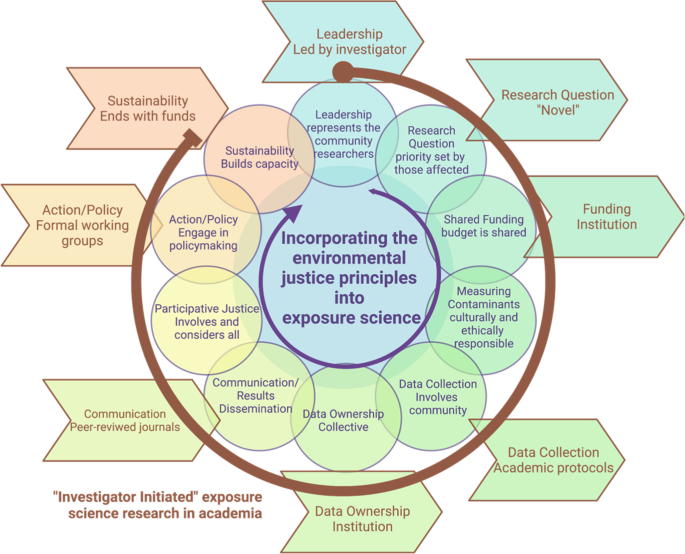

Exposure science is a multidisciplinary field that brings together researchers from various interdisciplinary areas that include risk assessment, epidemiology, public health, toxicology, environmental chemistry, public policy, and engineering [ 1 ]. At its core, exposure science seeks to answer basic questions such as: are people exposed to contaminant(s)? If people are exposed, what is the magnitude and intensity of the exposure(s) and what are the sources? Additional questions include: How are people exposed? What are critical routes and pathways of exposure? How can adverse exposures be mitigated? How can exposure mitigation strategies be sustainable? Answering these questions requires a detailed understanding of personal, cultural, behavioral, and political factors that contribute to these exposures, and how these vary by geographic regions, race, ethnicity, gender, socioeconomic status, and nationality [ 2 ]. Exposure science also seeks to better understand health risks associated with environmental exposures to inform exposure mitigation strategies suited for the affected population. While there is certainly value in this knowledge, we must dive deeper, as solely identifying exposures will not mitigate or prevent them. The view that science and data can speak for themselves has been widely accepted among scientists and perpetuated throughout the standard research process (Fig. 1 ). However, the traditional “investigator-initiated” academic approach rarely serves communities most affected nor leads to structural changes to improve public health. While the National Institutes of Environmental Health Science (NIEHS) translational research framework moves beyond the traditional “investigator-initiated” academic approach and highlights the importance of science informing practice and policy, it does not explicitly address structural racism as a root cause of health inequities [ 3 ]. Continuing to only characterize exposures without identifying root causes will not lead to meaningful changes, perpetuating distrust and failing affected communities. Herein, we bring a collective perspective to the exposure science field and advocate for community-driven approaches to not only identify harmful exposure(s), especially as they disproportionally affect marginalized communities, but to also reduce health disparities through community-centered approaches aimed at mitigating harmful exposures.

It demonstrates a roadmap showcasing the environmental justice framework for exposure science in comparison to the “Investigator Initiated” strategies to exposure science research in academia.

Over 30 years of research confirms that marginalized communities are disproportionately exposed to and affected by pollution [ 4 , 5 ], hazardous waste sites [ 6 ], lead poisoning [ 7 ], hazards resulting from the built environment [ 8 ], food deserts [ 9 ], and other harmful environmental exposures [ 10 ]. In 2020 and 2021, these marginalized communities were repeatedly told that due to their economic status, ethnicity/race, occupations, and home location they faced a higher risk of morbidity and mortality due to COVID-19 [ 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 ]. These are the same communities in which researchers have documented elevated exposures to air pollution [ 15 , 16 , 17 ], increased rates of contaminated drinking water [ 5 , 18 ], limited access to green spaces [ 19 , 20 ], and disproportionate burdens from climate change [ 21 ]. While the field has often reported an association between these “risk factors” (e.g., higher levers of air pollution) and race/ethnicity, it has done so without considering the interpretation of these associations, ignoring that structural racism and not race is responsible for these differential exposures. The difference between a “risk factor” and structural racism is that structural racism encompasses the systems that reinforce and perpetuate racial discrimination [ 22 , 23 , 24 ]. For example, while housing, education, employment, and health care access individually can be referred to as “risk factors” the interplay between all of these is structural racism [ 24 , 25 ]. This structure has led to disproportionate exposures and environmental injustices observed among marginalized communities. Marginalized communities continue to disproportionately face a mixture of harmful exposures [ 10 ], and socioeconomic inequality has grown [ 26 ], impacts from residential segregation persists [ 27 ], and many environmental exposure disparities have not been remedied [ 28 , 29 , 30 ].

Environmental justice (EJ) is defined as “the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people regardless of race, color, national origin, or income with respect to the development, implementation, and enforcement of laws, regulations and policies that affect the environment and/or public health” [ 31 , 32 , 33 ]. Since its inception, the EJ movement has been leading efforts to document environmental exposures and health conditions that reflect the values and needs of marginalized impacted communities [ 34 ]. The 17 Principles of Environmental Justice proposed at the First National People of Color Environmental Leadership Summit resonate just as strongly today as they did in the twentieth century (Table 1 ) [ 31 ]. The EJ movement calls for strict enforcement of informed consent, the right to a healthy environment, the need for involvement of all stakeholders in every step of the decision-making process, and public policy that is equitable. The Principles of Environmental Justice precede the 1994 federal Executive Order #12898 in the USA, which called for the integration of EJ in various branches of the government to serve “minority populations and low-income populations” [ 35 ]. Over the years, community-based EJ organizations have built power [ 36 , 37 ], EJ scholarship has grown [ 38 , 39 ], tools to assess and identify EJ communities have been developed [ 40 , 41 , 42 ], and research programs dedicated to combating environmental injustices have increased [ 43 , 44 ]. Nonetheless, despite these arduous efforts, progress is still needed in translating these 17 principles into policies to support systemic change to reduce exposure disparities that result from historical and contemporary racist policies.

Frontline EJ community members have long borne the burden of exposures and are often the first to ring the alarm on these harmful exposures [ 45 ]. For example, community anecdotes on how children of farmworkers would become exposed to pesticides simply by playing outside are now recognized exposure pathways [ 46 ]. What scientists now refer to as the “take-home” exposure pathway is a lived experience of parents who worried about exposing their kids through interacting with their children upon their arrival at home [ 46 ]. In response to the lack of government and industry inaction, communities at the fenceline of petrochemical industries developed their own “low-cost” tools to document their exposures to air pollution [ 47 ]. In one example, the use of these tools to assess air pollution was deployed by Communities for a Better Environment in collaboration with the Regional Accident Prevention Coalition in Contra Costa, CA, USA as far back as 1994. This community-driven approach in Contra Costa, known as the “bucket brigades”, integrated the principles of community-based participatory research (CBPR), EJ, and exposure science [ 47 ]. Traditional CBPR approaches that engage all partners in the research process offer yet a new dimension to advance EJ. Through a CBPR approach, partners can utilize their strengths to improve the health of the community and eliminate health disparities [ 48 ].

In 1999, Sexton and Adgate published a framework that established a conceptual roadmap to link sociodemographic variables and environmental health risks to disease by applying the Principles of Environmental Justice to environmental health [ 49 ]. One of the main arguments of Sexton and Adgate (1999) was that differences in race coupled with socioeconomic variables (e.g., income, education) could be linked to environmental health risks. However, race viewed as a variable in the Sexton and Adgate (1999) framework is not a robust proxy for racism. It is structural racism and not the color of people’s skin, itself that leads to these differential exposures and health risks [ 25 ]. Consequently, without addressing the racist policies and structures that contribute to race disparities, exposure disparities persist [ 28 , 49 ]. Gee and Paynes-Sturges (2004) took the EJ framework one step further and proposed that psychosocial stress was a factor that could link social conditions with environmental hazards [ 50 ]. As a result, the concept of exposure was expanded to include psychosocial factors. While structural factors are alluded to, these earlier academic frameworks have not explicitly identified structural racism as a root cause affecting disease or proposed community-driven approaches to combat the issue. Critical race theory (CRT) offers yet another layer to the discussion by explicitly attributing health disparities to structural racism and not race/ethnicity [ 51 ]. CRT is rooted in the idea that race is a social construct whereby social institutions such as the education system, housing market, criminal justice systems, health care system and others are governed by laws, regulations, rules, and protocols embedded with racism ultimately leading to disproportionate exposures, and inherently health outcomes [ 51 ]. Particularly for CRT, it calls for “centering in the margins”, which overlaps with the goal of CBPR, which is to collaborate through partnerships with communities, a theme also present in the EJ principles calling for equal partnerships in the decision-making process. An approach to integrating CRT into exposure science would be to remove race from models and instead incorporate variables related to the racism construct into the current methodology such as, for example, inclusion of residential segregation [ 51 ]. Despite several important overlapping principles, EJ, CBPR, and CRT have not been fully integrated into the academic scholarship of exposure science.

Many exposure scientists have been reluctant to explicitly identify structural racism as an amplifying factor in exposure disparities. One explanation for this is that exposure scientists may not see a direct connection between themselves individually, or to their research, and that the issue should be addressed by policymakers and community members. In addition, many exposure scientists have not had the requisite training or the lived experience (i.e., being a member of a marginalized community being studied) to identify structural racism as a root cause. To reduce EJ disparities that are pervasive across the critical issues being

addressed in exposure science, we must not take a passive approach to policymaking and need to improve active engagement in the policymaking process. Furthermore, exposure scientists need to expand their training to include CRT, CBPR, other social sciences, and be more representative of the communities in which they work [ 48 ]. The concept of research as a driving force for social change is not new. EJ methodologies have long been integrated into the public health field and its sub-disciplines, including exposure science. To truly integrate science to achieve change and to eliminate disparities plaguing marginalized communities, we call for the EJ principles to be fully integrated into the exposure science field.

Environmental justice framework components and principles

To encourage a rapid and pervasive adoption of the 17 Principles of Environmental Justice into exposure science, we propose a logical framework of 10 concepts that can serve as a roadmap for redefining how to conduct exposure science in a more just, inclusive, and equitable manner (Fig. 1 ). While it is recognized that each research study is different, and more importantly, each community is likely to have unique political, cultural, environmental, and/or social characteristics that affect their exposures, herein we distill and focus on a framework that transcends specific research questions or communities and aim to provide a path in which exposure science can actively engage to reduce environmental injustice.

Leadership—represent the community

Demands for increased diversity of faculty at academic institutions have been ongoing for decades. Each new wave of student cohorts across the nation calls for faculty that represent the diversity of the student population and the communities that they serve. In 2018, black researchers accounted for 8% of assistant professor appointments across the United States (US), Latino researchers for 6%, Asian and Pacific Islanders for 14%, multiracial researchers for 1%, and Indigenous researchers less than 1% [ 52 ]. In comparison, in 2018, the US population was 14.1% black, 18.3% Hispanic or Latino, 6.8% Asian, 0.4% Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander, 2.4% two or more races, and 1.7% American Indian and Alaska Native [ 53 ]. While there have been initiatives to increase the recruitment and retention of black, Indigenous and people of color (BIPOC) faculty, the representation of BIPOC researchers in academia tends to decrease at higher levels of the academic hierarchy. This underrepresentation is even greater in the science and engineering fields that form the foundation of exposure science [ 54 ]. A common discourse is that in order to increase the diversity at the faculty and senior levels of academia, we must also increase the diversity of students [ 55 ]. While there have been significant gains in the diversity of students at US higher education institutions from 1996 to 2016, this is not the case for faculty level [ 56 ]. This lack of diversity in leadership means that research will continue to be led by scientists that do not represent the communities with which they engage. An EJ framework for exposure science means recruiting and retaining academic colleagues that not only understand the socio-cultural complexities of the communities they work with, but also have the lived experience from being a part of these communities themselves. This lived experience can be instrumental in establishing trust with community-based organizations, which will result in “authentic allyships” in research studies that seek to make structural changes [ 57 ]. Intentionally building partnerships with EJ communities could result in members of these communities being recruited and retained as academic colleagues. Furthermore, investing in programs such as NIHs career Faculty Institutional Recruitment for Sustainable Transformation initiative that aims to provide funding for institutions to recruit and retain faculty who have a demonstrated commitment to inclusive excellence provides a way forward to reducing this academic leadership disparity [ 58 ].

Research questions—priority set by those most affected

The field of exposure science, like medicine, has largely been shaped by academic researchers, the business community and government agencies, which drive the choice of research questions, study design, and the norm of data interpretation [ 59 ]. Many of these institutions create and regulate environmental hazards of concern that disproportionately burden marginalized communities [ 28 , 50 ]. Over the past two decades, the exposure science field has shifted from a one-exposure-at-a-time approach to a more integrated approach that considers multiple exposures across space and time [ 60 ]. Measuring the exposome, the totality of life-course exposures, as a framework to systematically evaluate environmental contributors to health and disease is a novel approach to exposure assessment. The exposome concept has been expanded to include lifestyle and social factors (e.g., diet, stress, neighborhood quality, smoking, chemicals, drugs, microbes) and internal biological processes and responses [ 61 ]. This expansion has often been driven by new technologies, including new “omics” technologies such as transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics, and these are increasingly valued in exposure science, while research focused on disparities and inequities is sidelined as “pedestrian” [ 62 ]. The topic of health disparities research often fails to receive favorable marks during grant reviews in the innovation sector when reviewed with the significance, investigators, approach, and environment [ 62 ]. Furthermore, disease-specific study sections common in environmental health rarely include exposure scientists and those with similar expertise that can critically review grants through this lens. In addition, they lack reviewers with expertise in considering how addressing policies or systematic racism fit within the biomedical model. As many study sections require reviewers to have been previously successful in obtaining independent research funding, the lack of representation amongst academic researchers perpetuates to those that are eligible to serve on grant review committees and with funding decisions [ 63 ]. Only recently have federal granting agencies voiced their commitment to ending structural racism in the biomedical research landscape and issued specific structural racism granting mechanisms [ 64 ].

The EJ movement has advanced our knowledge about disparities in exposures and health conditions that reflect the values and needs of affected communities. To uphold an EJ framework for exposure science, the value of research relies on its ability to help answer questions about local concerns (e.g., Is it safe to drink water from my well? What is the cause of the noxious odors in my neighborhood and is it only a nuisance or a true hazard of concern?), and the ability to present local concerns to inform prevention approaches to reduce exposure to hazardous chemicals [ 36 ]. Participation of community-based environmental and civil rights groups in the development and implementation of environmental exposure studies extends the impact and breadth of scientific research [ 65 ]. Community-engaged and community-driven models are shown to be more effective to advance public health than top-down strategies [ 66 , 67 ] and more likely to be sustained when grounded in local systems and culture [ 68 , 69 ].

Shared funding—shared budget

Exposure science is commonly supported by research grants from government agencies, foundations, or other funding entities, and proposals often require statements on how the study may lead to broader societal impacts. While broader impact statements can range in type and focus, they often include elements of environmental injustice reduction. Meeting these broader impact goals usually becomes the responsibility of the researcher and the community under study, often with no funds and resources to achieve this, while the institutions maintain an inactive or more passive role.

Unequal resource allocation perpetuates injustices in exposure science as institutions consume a large proportion of community-based research funding, leaving communities with very little. Centering EJ in exposure research will require changing the budgetary paradigms that drive much of the research today. As a start to establishing a more equitable resource allocation, investigators must improve their engagement, partnership and transparency with the communities they study, including honest discussions about the community-focused funding necessary to accomplish study aims. This engagement partnership should start at the proposal development stage and cannot be a pro forma afterthought. If increasing community engagement is a stated study deliverable, then it must be reflected in the budgetary request to sponsors. Secondly, modest but meaningful cost-sharing mechanisms should provide resources to elevate the voices in these EJ communities. It should also eliminate funder-imposed barriers for items like translation services, community member travel costs, childcare, and meals for the community. Community members should also not be expected to provide significant services without discussion of compensation for the time and effort involved before the project is launched. These modifications could be accomplished by institutions voluntarily establishing EJ-focused cost-sharing designed to issue indirect resources, or by cost-sharing mandates from the funding agencies as a condition of award acceptance. There is also a need to reduce institutional barriers for community organizations to participate, this includes university-style budgeting and reporting requirements, NIH-style curriculum vitae (i.e., bio-sketches) for community members, and a pervasive and unnecessary lag in expense reimbursements. These changes would allow the institution to support community-needed costs and reduce participation barriers for community members. They will also facilitate compliance with the terms and conditions of grant writing agencies. Equitable and fair funding sharing would reduce current resource disparities between research institutions and affected communities.

Measuring contaminants—culturally and ethically responsible

Exposure scientists must select the appropriate instruments, which include surveys/questionnaires and monitoring tools to collect information on the contaminants studied, and, in addition, pay more attention to who is collecting this data. Involving community members, students, and other researchers who are members of the communities we work with during the study instrument development phase and in the collection of data is key to capturing robust data, building capacity, trust, and advancing equitable exposure science. Advancements in technology have now introduced the academic landscape to even more low-cost participatory monitoring tools that can be leveraged with community members to build capacity. As an example, EJ groups around the country are building their own air monitoring networks to track their own neighborhood air quality [ 70 ]. While there are measurement precision costs in using low-cost monitoring tools, a community–university collaboration would allow for EJ groups to obtain and validate their own data, while maintaining autonomy. This approach to exposure science will ensure that we are not only using the latest advances in community-accessible technology, data visualization, and interpretation, but that we are collecting what our communities deem a priority. This is key to upholding the Principles of Environmental Justice, particularly principle 5 that calls for the right to “…environmental self-determination of all peoples” [ 31 ]. Furthermore, through this participatory science approach, scientists can learn about the cumulative exposures of concern in the community, leading to a more accurate exposure assessment representative of the target community.

The focus and disproportionate resources given to bio-banking, a process used to collect samples of bodily fluid or tissue for research purposes, has often dismissed the cultural appropriateness of collecting these biological samples [ 71 , 72 ]. Funding agencies have been heavily criticized for approaching bio-banking from an extractive framework that prioritizes maximizing sample size and capitalizing on already collected samples while dismissing inclusiveness and respect [ 73 ]. This extractive approach has often plagued exposure science, which has been dominated by scientists that do not have an understanding of the damage research has done in the past to BIPOC communities [ 74 , 75 ]. For example, in one study on interventions to reduce blood lead levels in children, academic researchers did not disclose the high blood lead levels of children enrolled in an intervention study. This left parents and children unaware of their high blood levels, potentially preventing them from seeking care to reduce these blood levels, and ultimately led to families utilizing the legal system to demand reparations [ 76 ]. An EJ approach to biological sample collection would ensure that community members are part of the study design, decisions, and that appropriate cultural and ethical considerations are prioritized, and that, if samples are to be bio-banked, appropriate provisions are instituted for their future use with a focus on benefiting the community from which they are obtained.

Data collection—involve community

Using the CRT model for guidance, scientists must tailor their research toward the needs of the target population and consider environmental factors, population characteristics (predisposing, enabling, and need factors), and health/behavioral outcomes when creating the study design [ 51 ]. Prior to collecting these data, exposure scientists should foster trust within the community through cultural education from community members [ 77 ]. This practice is likely to vary from community to community and thus requires that researchers center the voices of community members and strive for authentic collaborative partnerships with EJ groups. For example, through a community-academic partnership, investigators from the University of Southern California collaborated with East Yards Communities for Environmental Justice to successfully gather bio-samples, in this case teeth from Latino children [ 78 ]. This partnership, coined the Truth Fairy Project , began many years before the collection of samples and continues to live on through projects aimed at generating data to support policy action and not just documenting injustices [ 79 ]. In addition, investigators should create efficient and effective processes to include community members throughout the research process, including study design, execution, and dissemination of results. Scientists must develop an understanding of local knowledge, and co-learning within the community [ 77 , 80 , 81 ]. This co-learning method is a group learning approach that improves “communication skills, cultural awareness, and thinking skills” [ 82 ]. To foster co-learning, institutions and agencies must provide support for their researchers to conduct training in multiple languages. These practices will ensure that the research findings are effectively disseminated to the community to improve the health of the target population [ 77 ].

Data ownership—collective

Examples of unethical cases of data and sample ownership that plague the scientific field are numerous. From the commercialization of Henrietta Lacks cells, to the misuse of Havasupai Tribe blood samples for genetic testing and the ongoing discourse of data-sharing agreements, there is no shortage of historical and current lessons that scientists can incorporate into their field of practice [ 74 , 83 , 84 , 85 , 86 ]. The exposure science field is held to ethical standards through the Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval process and our peer-reviewed manuscripts include a statement on participant consent, there is rarely any mention and discussion on the accessibility and ownership of the data. Indigenous people are leaders in this effort as they have been leading and fighting for their right to govern their own data (i.e., data sovereignty). An example is the Navajo Nation Human Research Review Board (NNHRRB) that is led by members of the Navajo Nation and that reviews all IRB-approved studies being conducted on the Navajo Nation. In addition to IRB oversight, the NNHRRB requires that any scholarly or community presentation on an open research project be presented to them first, that all publications be submitted to them for approval, and that all data be given back to them at the conclusion of a project. Models of strong data ownership agreements are available. One example of strong data ownership includes the one developed by the Swinomish Indian Tribal Community, a sovereign tribal nation in Washington, and another nation the Tsleil-Waututh First Nation in British Columbia [ 87 ]. The agreement and the decision-making processes and protocols developed served as effective governance mechanisms because both nations retained complete ownership over their respective data and agreements called for data to be reviewed and approved by its leadership prior to its release. The agreement also required that tribes be named as co-authors in all related publications, which is another mechanism through which sovereign nations can exercise control over the dissemination of research findings on their terms [ 88 ]. Similarly, one robust example of community-owned and managed research (COMR) includes the West End Revitalization Association’s (WERA) efforts in response to civil rights and EJ issues, including the absence of infrastructure related to water and waste management and prevalent health disparities in low-income communities of color in Mebane, North Carolina. WERA is a community-based environmental protection organization that developed a research framework known as COMR. This framework allowed impacted community members to play the role of principal investigator in the research process, actively collect data and own the data produced to implement changes in their community [ 57 , 89 ]. A robust and inclusive EJ framework would ensure that the data collected from communities is conducted through an equitable lens, that the community decides what the information can and cannot be used for, and that there are processes in place to ensure its shared governance. As these important steps can increase the time to publication, but are essential for authentic collaborative research, funding agencies and tenure committees should also directly acknowledge the importance and value of this process.

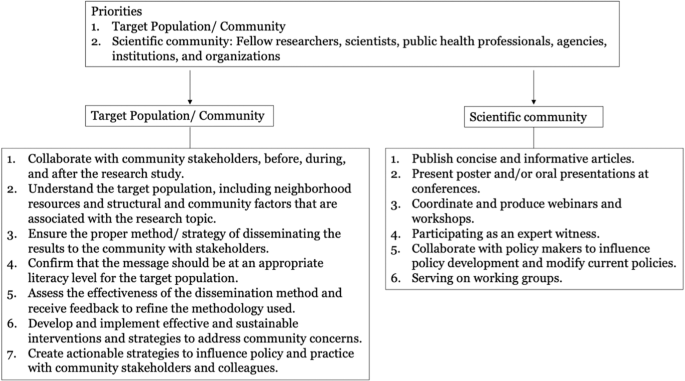

Communication/results dissemination

Historically, exposure science researchers have assumed a “the science speaks for itself” attitude, a perspective perpetuated by the dissemination of research primarily via manuscripts and conference presentations. In the EJ framework, it is important to ensure that the communities being studied become part of the dissemination strategy. Translating exposure science data into accessible knowledge that can inform community actions and interventions, is valuable and necessary. Sharing research results with the community is essential to increase knowledge within the communities and promote evidence-based policy for optimal health outcomes. Dissemination through a co-learning approach may include translation of materials and development of clear messaging around results and guidance on actions to reduce exposure(s) of concern (Fig. 2 ). While dissemination of research results is beginning to grow, there are several groups to turn to for guidance. For example, researchers from Silent Spring have successfully communicated results using digital web-based formats [ 90 ], while researchers from the University of Arizona partnered with Community Health Representatives to deliver study results to participants [ 91 ]. Engaging youth offers yet another invigorating method to deliver research results, as is the case of researchers from the Center for Environmental Research and Children’s Health [ 92 ]. Through their innovative participatory approach, youth were engaged not only in the design but also communication of findings through workshops, videos, and multi-media campaigns. While already a component of the NIEHS “Research to Action” program, researchers and their community collaborators need to incorporate this into their timeline, budget, and evaluation of their projects during the development stage.

It showcases a framework that can be utilized to disseminate research for environmental justice. Dissemination should be prioritized towards two specific groups: the target population and community, and the scientific community. It provides best practices particular to each population.

Advances in exposure science over the last 30 years have led to a need for guidance for the ethical reporting of exposure results to participants. This is particularly important when there is no clear outcome or interpretation of the results [ 93 ]. However, the relationship between measured exposure values and environmental health outcomes for many chemicals in use today remains unknown. Consequently, there are very few guidelines available today showcasing communication in personal exposure assessment research [ 94 ]. Historically, epidemiologists have claimed it is unethical to provide results to participants without clear established levels for interpretation, and that it would interfere and invalidate observational studies [ 93 ]. In this respect, exposure science is unique; levels associated with environmental health outcomes cannot be determined without first measuring the exposure. Exposure assessment thus often involves grappling with exposure values for which there is no clear interpretation [ 94 ]. However, this approach is evolving. Researchers report that participants have generally been able to manage anxiety arising from receiving results even when there are no clear health guidelines [ 95 ] and lessons for communication have been drawn from other fields [ 96 ]. The California Environmental Biomonitoring Program is required by statute to report all results to participants and as such has pioneered approaches for the release of results on complex chemical exposure to its participants [ 97 ]. Sometimes the results may be received after the research funding is ended. Again, as stated above, institutions or funding agencies could mandate funds for results report back to communities from EJ community-based research and for evaluation of those processes.

The EJ framework presented herein takes a multidirectional approach and proposes that the community should receive the research results before they are disseminated to the broader scientific community. Scientists able to interpret and present their findings and caveats in conference presentations and publications should also be able to present them to the community that provided them the samples. These presentations should include accessible explanations of the limitations and uncertainty of the study. Transparency should start prior to sample collection, so that the communities understand the limitations of the data to be collected and its interpretation. This transparency is particularly important in interpreting the exposures of underserved and understudied communities who may be most vulnerable. This may be achieved during the planning stages of the study in the community-engagement phase. While the peer-review process does add scientific validity to the findings, the long wait time between initial submission to publication means that participants may be placed in a state of uncertainty until individual or community dissemination occurs. Depending on the findings an appropriate timeline in coordination with community partners is an approach to determine when to best synthesize and report back study findings. The plan for data communication and dissemination should also be covered during the consenting process. While methodologies are still developing for the appropriate evaluation of the reporting back results, it is essential that we understand how communities are using this information to advance the environmental health and justice [ 98 , 99 ].

Relying on communities as experts due to their lived experiences and how this expertise can be incorporated to advance partnerships is highlighted in the EJ principles (principle number 16). Through Ford and Airhihenbuwa’s (2010) Critical Race Framework, a similar concept is referred to as “Experimental Knowledge”, which overlaps with the educational term “Funds of knowledge” [ 51 , 100 ]. This concept refers to “historically accumulated and culturally developed bodies of knowledge and skills essential for household or individual functioning and well-being” [ 61 ], in other words, due to their lived experiences community members possess invaluable knowledge that can be incorporated throughout the research design and dissemination strategy [ 61 ]. This practice will increase the effectiveness of the intervention while improving the scientific knowledge of the specific topic area within the community.

Participative justice—involves and considers all

Equitable access to the benefits of exposure science raises concerns about participatory justice. This term refers to the direct participation of those most affected by a particular decision or policy. All communities involved should participate and benefit from exposure science activities in equitable ways. As an example, the state of California started community-led air pollution monitoring mandated by Assembly Bill 617 that seeks to address persistent air pollution hotspots in disadvantaged communities [ 101 ]. The California Air Resources Board (CARB) established a process through which communities can apply for enhanced monitoring and mitigation efforts CARB 2020. This avenue provides funding and increases attention to local EJ concerns, like those near the Port of Sacramento [ 102 ].

Although well intentioned, directing resources to communities could lead to skewed attention and funding toward communities with already well-established environmental and/or social justice organizations. For example, the list of applicants to the first round of the CARB Community Air Grant (in 2019) had many more applicants than could be awarded. Each application represented significant coordinated efforts and time for the applicants [ 102 ]. Communities with significant air exposures that lacked an experienced organization to prepare the application were missing from this list. In the proposed EJ framework, all communities would benefit from and participate in exposure science activities and achieve EJ, including those lacking the infrastructure, time, energy, and financial resources to coordinate such efforts. To make this possible, exposure scientists and funding agencies should actively support the participation of marginalized communities and direct resources such as paid internships or additional funding to the communities and assist them in applying for awards. In addition, barriers to ongoing community participation should be assessed and funds used to mitigate these barriers.

Action/policy—engage in policymaking

An EJ framework to exposure science engages a wide range of stakeholders and place the communities at the forefront. It is critical to consider the wide range stakeholders, inching policymakers, regulatory agencies, grassroots, and national non-profit organizations needed to move research toward actual change. Each of these stakeholders operates in a different sphere and tying these spheres together through an EJ framework is critical for reducing exposures. It is not enough for scientists to recommend individual reduction exposure behaviors; the field must evolve, identify, and demand structural changes. Training for exposure scientists must be interdisciplinary and address the importance of incorporating an understanding of the social and structural determinants of health for advocacy and action for effective public health change.

Traditional environmental health research that ends in a publication of no interest to the community or to policymakers charged with their protection is archaic. We are not calling for the end of publications, rather for community-driven science to not only develop scientific evidence but also to achieve engagement and action through an equitable, participative, and action-oriented process. Enacting local policies requires knowledge and access to yet a different set of players and rules, and most communities, scientists, and stakeholders are often unfamiliar, or unaware, of these critical individuals or groups. Some of this gap in knowledge is often filled by non-governmental organizations, who serve critical roles in building bridges with academic institutions and policymakers. While challenging, exposure scientists must incorporate an EJ framework to their work. This involves providing public comment on regulatory documents, serving on advisory boards, or actively engaging in workgroups. Ideally, these would be done alongside community members whose “funds of knowledge”, testimonials, and status as constituents have the collective power to enact real change [ 100 , 103 ]. As these actions are often needed after the research funding has ended, to pay for efforts in this area, such as time for students/research assistants, institutions could voluntarily establish EJ-focused cost-sharing designed to release indirect resources, or there could also be cost-sharing mandates from the funding agencies as a condition of award acceptance. Federal grant funding agencies could also mandate that a certain percentage of the funds go toward investing time toward capacity building and translation/policy activities. Such funds could be used to support efforts either from the researcher/institution, by the NGO or community to disseminate findings to stakeholders and to prepare policy briefs and other actionable documents.

Sustainability—build capacity

Sustainability of interventions and exposure mitigation strategies aimed at reducing the risk of harm and adverse health effects is paramount in marginalized communities suffering environmental health disparities. By sustainability, we mean implementing changes and knowledge gained via the research process that meets present needs without compromising the ability of future generations in the affected communities to meet and safeguard said changes. However, said sustainability is often dismissed, not incentivized, and not without its challenges to implement by both researchers and community stakeholders in the affected communities.

Current research practices often focus on initiating partnerships with affected communities to conduct the research. However, more often than not, these partnerships cease when all of the research data are collected, leaving communities alone to fight for action on the findings and never to hear from researchers again. Communities may be left with more questions than sustainable solutions to their environmental problems. Several factors may explain why said partnerships are not successful. First, building relationships and trust, establishing partnerships, and retaining those partnerships with impacted communities is labor and resource intensive. Establishing these partnerships can take months to years to build and requires that researchers effectively engage affected communities throughout the research process. Often, researchers are also not equipped with the appropriate staff and research team to engage with target communities, nor do they invest in providing the affected communities with resources to mitigate environmental health disparities. Still, it is important to highlight examples of successes in CBPR in exposure science. One such example includes initiatives conducted as part of the Center for the Health Assessment of Mothers and Children of Salinas (CHAMACOS) Study. CHAMACOS is the longest-running longitudinal birth cohort study of pesticides and other environmental exposures among children in a farmworker community in California. Programs such as the CHAMACOS Youth Council developed in collaboration with local community partners train local Latino youth in research design and implementation, promote environmental health literacy, and engage youth in advocacy and outreach [ 92 ]. As part of this program, trained youth have conducted field data collection that not only helps to promote careers in exposure science by exposing youth to the field, but also contributes to the success of ongoing studies, including those focusing on youth. In addition, the CHAMACOS study has successfully engaged members from underrepresented groups for training in environmental health sciences at all graduate and postgraduate levels helping to increase the pipeline in the field.

An EJ approach recognizes that community-engaged research is one key method for the suitability of partnerships [ 57 ]. Successful research teams not only recruit participants from EJ communities for their research studies, but also hire community members as part of their staff. A comprehensive team approach informs the research process and can support recruitment and data collection efforts. Moreover, it can help research teams understand the culture and practices of their target population, and the tools needed to be implemented to develop sustainable intervention strategies. Research in marginalized communities also needs to strive toward establishing and developing strategies to effectively build trust with these populations so that the burden does not fall entirely on new investigators who may not always have the necessary institutional support required to move forward during and after their research funding has ended.

A comprehensive EJ framework is necessary to ensure sustainability and requires implementation of a multi-pronged approach that includes co-leading, co-training, involves including junior investigators, ethnically and racially diverse research teams and leadership, capacity building, community mentors, and seeks to identify and implement evidence-based solutions that are sustainable.

Exposure science research has focused on the study of stressors and receptors in the context of space and time at the ecologic, community, and individual level. Nonetheless, hazard identification in the absence of social justice can exacerbate disparities in marginalized communities [ 104 ]. For example, following the quantification of harm associated with the chemical bisphenol A (BPA), exposure decreased among populations able to access alternative products, but BPA exposures were highest among low-income communities and those facing food insecurity [ 105 , 106 ]. Another example is the identification of high levels of flame retardants in the bodies of residents of California, which led to the phasing out of some of these chemicals in new furniture, but continued exposure was documented for lower-income populations through their continued use of older or reused furniture [ 107 , 108 ].

Exposure science needs to move beyond the individual and the mechanistic approach [ 109 ]. This is most evident in current exposome applications which are oriented toward personalized medicine [ 110 ]. As stated in Nwanaji-Enwerem et al. (2021), adopting a “compound” exposome approach would be an important step toward incorporating equity and EJ into exposure science [ 110 ]. That is to move from this individual approach, communities and human populations—and their exposures—should be seen as complex societies with economic relations, social classes, racism, sexism, cultural practices, and relationships to other species [ 2 , 109 ]. This framework seeks to uplift the expertise and data from community organizations and the EJ movement, who are increasingly turning toward gathering their own data to understand their local environment and document environmental hazards [ 111 ]. Marginalization is not exclusive to race but it is often that exposures disproportionally affect communities of color [ 4 ]. Intersectionality offers a lens to analyze and incorporate attributes, such as LGBTQ identity, and disability, which are not discussed thoroughly in the EJ scholarship [ 112 , 113 ]. Furthermore, peer-reviewed journals can help amplify this scholarship by calling for special issues and integrating researchers into their editorial boards whose methodology centers CRT, intersectionality, CBPR, and EJ.

Researchers should meet with community members and stakeholders to learn more about the community, involve them in the research process, collectively determine the environmental exposure issues of highest concern for the community, and develop sustainable interventions and implementation strategies to address them. Incorporating community “funds of knowledge” will also inform the study design by incorporating the knowledge about the issue that community members have based on their lived experiences [ 100 , 103 ]. Institutional and funding agency funds should also be directed to supporting community needs both during the research and needs for dissemination, policy briefs, and other action at the conclusion of the research. This multidirectional framework for exposure science will increase the sustainability of the research and its impact for long-term success. In addition, involving the community in the research project, from start to finish, will facilitate community learning about exposure science and how it relates to the health of all those involved. It will also provide researchers with better knowledge of human behaviors, activities, and risk perceptions that may impact exposures, and improve researcher competency in assessing exposures. An EJ approach will increase a sense of belonging and improve communication among the community, the researchers, and other organizations involved [ 103 ].

Furthermore, it is not enough to document the continued exposure and environmental health disparities in structurally marginalized communities. We call for the incorporation of the EJ principles (Table 1 ) in exposure science to be the norm and not just words (Fig. 1 ). Along with critically engaging with this perspective, we hope to amplify the voices of those who are historically excluded in this work. As members of the research community from different sectors (e.g., academic, governmental, or non-profit institutions) and diverse backgrounds and lived experiences, we will seek to become better mentors, work toward institutional change that values and rewards EJ principles and speak up against injustices.

Definitions

Marginalized communities are groups and communities that experience discrimination and exclusion (social, political, and economic) because of unequal power relationships across economic, political, social, and cultural dimensions.

Lioy PJ. The 1998 ISEA Wesolowski Award Lecture Exposure analysis: reflections on its growth and aspirations for its future. J Expo Anal Environ Epidemiol. 1999;9:273–81.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Juarez PD, Matthews-Juarez P, Hood DB, Im W, Levine RS, Kilbourne BJ, et al. The public health exposome: a population-based, exposure science approach to health disparities research. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2014;11:12866–95.

Article Google Scholar

Translational Research Framework. https://www.niehs.nih.gov/research/programs/translational/framework-details/index.cfm . Accessed 2 Jan 2022.

Liu J, Clark LP, Bechle MJ, Hajat A, Kim SY, Robinson AL, et al. Disparities in air pollution exposure in the United States by race-ethnicity and income, 1990-2010. Environ Health Perspect. 2021;129:127005.

Nigra AE, Chen Q, Chillrud SN, Wang L, Harvey D, Mailloux B, et al. Inequalities in public water arsenic concentrations in counties and community water systems across the united states, 2006–2011. Environ Health Perspect. 2020;128:1–13.

Mohai P, Saha R. Racial inequality in the distribution of hazardous waste: a national-level reassessment. Soc Probl. 2007;54:343–70.

Teye SO, Yanosky JD, Cuffee Y, Weng X, Luquis R, Farace E, et al. Exploring persistent racial/ethnic disparities in lead exposure among American children aged 1–5 years: results from NHANES 1999–2016. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2021;94:723–30.

Hutch DJ, Bouye KE, Skillen E, Lee C, Whitehead L, Rashid JR. Potential strategies to eliminate built environment disparities for disadvantaged and vulnerable communities. Am J Public Health. 2011;101:587–95.

Walker RE, Keane CR, Burke JG. Disparities and access to healthy food in the United States: a review of food deserts literature. Health Place Pergamon. 2010;16:876–84.

Nguyen VK, Kahana A, Heidt J, Polemi K, Kvasnicka J, Jolliet O, et al. A comprehensive analysis of racial disparities in chemical biomarker concentrations in United States women, 1999–2014. Environ Int. 2020;137:105496.

Meltzer GY, Avenbuan O, Awada C, Oyetade OB, Blackman T, Kwon S, et al. Environmentally marginalized populations: the “perfect storm” for infectious disease pandemics, including COVID-19. J Health Dispar Res Pract. 2020;13:68–77.

Ruprecht MM, Wang X, Johnson AK, Xu J, Felt D, Ihenacho S, et al. Evidence of social and structural COVID-19 disparities by sexual orientation, gender identity, and race/ethnicity in an urban environment. J Urban Heal J Urban Health. 2020;98:27–40.

Garcia E, Eckel SP, Chen Z, Li K, Gilliland FD. COVID-19 mortality in California based on death certificates: disproportionate impacts across racial/ethnic groups and nativity. Ann Epidemiol. 2021;58:69–75.

Carrión D, Colicino E, Pedretti NF, Arfer KB, Rush J, DeFelice N, et al. Neighborhood-level disparities and subway utilization during the COVID-19 pandemic in New York City. Nat Commun. 2021;12:3692.

Woo B, Kravitz-Wirtz N, Sass V, Crowder K, Teixeira S, Takeuchi DT. Residential segregation and racial/ethnic disparities in ambient air pollution. Race Soc Probl. 2019;11:60–7.

Miranda ML, Edwards SE, Keating MH, Paul CJ. Making the environmental justice grade: the relative burden of air pollution exposure in the United States. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2011;8:1755–71.

Terrell KA.James W. Racial disparities in air pollution burden and COVID-19 deaths in Louisiana, USA, in the context of long-term changes in fine particulate pollution. Environ Justice. 2020;1–8..

Schaider LA, Swetschinski L, Campbell C, Rudel RA. Environmental justice and drinking water quality: are there socioeconomic disparities in nitrate levels in U.S. drinking water?. Environ Health. 2019;18:1–15.

Rigolon A, Browning M, Jennings V. Inequities in the quality of urban park systems: an environmental justice investigation of cities in the United States. Landsc Urban Plan. 2018;178:156–69.

Wen M, Zhang X, Harris CD, Holt JB, Croft JB. Spatial disparities in the distribution of parks and green spaces in the USA. Ann Behav Med. 2013;45:18–27.

Hsu A, Sheriff G, Chakraborty T, Manya D. Disproportionate exposure to urban heat island intensity across major US cities. Nat Commun. 2021;12:1–11.

Google Scholar

Castle B, Wendel M, Kerr J, Brooms D, Rollins A. Public health’s approach to systemic racism: a systematic literature review. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2019;6:27–36.

Hardeman RR, Murphy KA, Karbeah J, Kozhimannil KB. Naming institutionalized racism in the public health literature: a systematic literature review. Public Health Rep. 2018;133:240–9.

Bailey ZD, Krieger N, Agénor M, Graves J, Linos N, Bassett MT. Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: evidence and interventions. Lancet. 2017;389:1453–63.

Adkins-Jackson PB, Chantarat T, Bailey ZD, Ponce NA. Measuring structural racism: a guide for epidemiologists and other health researchers. Am J Epidemiol. 2021;00:1–9.

Song X, Lachanski MS, Coleman TS. Three myths about US economic inequality and social mobility. Capital Soc. 2021;15:1–19.

Krieger N, Van Wye G, Huynh M, Waterman PD, Maduro G, Li W, et al. Structural racism, historical redlining, and risk of preterm birth in New York City, 2013-2017. Am J Public Health. 2020;110:1046–53.

Alvarez CH, Evans CR. Intersectional environmental justice and population health inequalities: a novel approach. Soc Sci Med. 2021;269:113559.

Tsosie R. Indigenous peoples and the ethics of remediation: redressing the legacy of radioactive contamination for native peoples and native lands. St Cl J Int Law. 2015;13:203–72.

Kiaghadi A, Rifai HS, Dawson CN. The presence of Superfund sites as a determinant of life expectancy in the United States. Nat Commun. 2021;12:1–12.

Summit FNP of CEL. The Principles of Environmental Justice (EJ). October 1991.

Environmental Justice | US EPA. https://www.epa.gov/environmentaljustice . Accessed 31 Jan 2022.

Lee C. Evaluating Environmental Protection Agency’s definition of environmental justice. Environ Justice. 2021;14:332–7.

Bullard RD. Solid waste sites and the black Houston community. Socio Inq. 1983;53:273–88.

Federal Register. Executive Order 12898. Fed. Actions To Address Environ. Justice Minor. Popul. Low-Income Popul. 1994.

Petersen D, Minkler M, Vásquez VB, Baden AC. Community-based participatory research as a tool for policy change: a case study of the Southern California Environmental Justice Collaborative. Rev Policy Res. 2006;23:339–54.

Minkler M, Vásquez VB, Tajik M, Petersen D. Promoting environmental justice through community-based participatory research: the role of community and partnership capacity. Heal Educ Behav. 2008;35:119–37.

Perez AC, Grafton B, Mohai P, Hardin R, Hintzen K, Orvis S. Evolution of the environmental justice movement: activism, formalization and differentiation. Environ Res Lett. 2015;10:1–12.

Mohai P, Pellow D, Roberts JT. Environmental justice. Annu Rev Environ Resour. 2009;34:405–30.

Cushing L, Faust J, August LM, Cendak R, Wieland W, Alexeeff G. Racial/ethnic disparities in cumulative environmental health impacts in California: evidence from a Statewide Environmental Justice Screening Tool (CalEnviroScreen 1.1). Am J Public Health. 2015;105:2341–8.

Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment. California Communities Environmental Health Screening Tool, Version 3.0 (CalEnviroScreen 3.0). 2018. p. 2–5. https://oehha.ca.gov/calenviroscreen/report/calenviroscreen-30 .

Eisenhauer E, Williams KC, Warren C, Thomas-Burton T, Julius S, Geller AM. New directions in Environmental Justice Research at the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: incorporating recognitional and capabilities justice through health impact assessments. Environ Justice. 2021;14:322–31.

Environmental Health Disparities and Environmental Justice. https://www.niehs.nih.gov/research/supported/translational/justice/index.cfm . Accessed 2 Jan 2022.

EPA Announces $50 Million to Fund Environmental Justice Initiatives Under the American Rescue Plan | US EPA. https://www.epa.gov/newsreleases/epa-announces-50-million-fund-environmental-justice-initiatives-under-american-rescue . Accessed 20 Dec 2021.

United Church of Christ. Toxic Wastes and Race. 1987.

Perils of Pesticides Address to Pacific Lutheran University. 1989. https://chavezfoundation.org/speeches-writings/#1549063588679-ed96425e-7969 .

Susag K, Fishman S, May J, Larson D. The Bucket Brigade Manual. 1998.

Wallerstein NB, Duran B. Using community-based participatory research to address health disparities. Health Promot Pract. 2006;7:312–23.

Sexton K, Adgate JL. Looking at environmental justice from an environmental health perspective. J Expo Environ Epidemiol. 1999;9:3–8.

Gee GC, Payne-Sturges DC. Environmental health disparities: a framework integrating psychosocial and environmental concepts. Environ Health Perspect. 2004;112:1645–53.

Ford CL, Airhihenbuwa CO. Critical race theory, race equity, and public health: toward antiracism praxis. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:693–8.

U.S. Department of Education. The Condition of Education 2020. 2020.

U.S Population. Census’ Am. Community Surv. 1-year Estim. 2018.

The State of U.S. Science & Engineering. 2020 Natl. Sceince Board Sci. Eng. Indic. 2020. https://ncses.nsf.gov/pubs/nsb20201/preface .

Griffin KA. Reconsidering the pipeline problem: increasing faculty diversity. 2016. https://www.higheredtoday.org/2016/02/10/reconsidering-the-pipeline-problem-increasing-faculty-diversity/ .

Taylor M, Turk JM, Chessman HM, Espinosa LL. Race and ethnicity in higher education spotlight. 2020.

Davis LF, Ramírez-Andreotta MD. Participatory research for environmental justice: a critical interpretive synthesis. Environ Health Perspect. 2021;129:1–20.

Faculty Institutional Recruitment for Sustainable Transformation (FIRST) | NIH Common Fund. https://commonfund.nih.gov/first . Accessed 2 Nov 2021.

Wing S. Social responsibility and research ethics in community-driven studies of industrialized hog production. Environ Health Perspect. 2002;110:437–44.

National Research Council. Exposure science in the 21st century: a vision and a strategy. National Academies Press: Washington, DC. 2012.

Rappaport SM, Smith MT. Environment and disease risks. Science. 2010;330:460–1.

Carnethon MR, Kershaw KN, Kandula NR. Disparities research, disparities researchers, and health equity. JAMA 2020;323:109–28.

Hoppe TA, Litovitz A, Willis KA, Meseroll RA, Perkins MJ, Hutchins BI, et al. Topic choice contributes to the lower rate of NIH awards to African-American/black scientists. Sci Adv. 2019;5:1–13.

Collins FS, Adams AB, Aklin C, Archer TK, Bernard MA, Boone E, et al. Affirming NIH’s commitment to addressing structural racism in the biomedical research enterprise. Cell. 2021;184:3075–9.

Balazs CL, Morello-Frosch R. The three Rs: how community-based participatory research strengthens the rigor, relevance, and reach of science. Environ Justice. 2013;6:9–16.

Wallerstein NB, Yen IH, Syme SL. Integration of social epidemiology and community-engaged interventions to improve health equity. Am J Public Health. 2011;101:822–30.

McLeroy KR, Norton BL, Kegler MC, Burdine JN, Sumaya CV. Community-based interventions. AJPH. 2003;93:344–8.

Duran BG, Wallerstein N, Miller WR. Interventions for alcohol problems in minority and rural populations: the experience of the Southwest Addictions Research Group. Alcohol Treat Q. 2007;25:1–10.

Altman DG. Challenges in sustaining public health interventions. Heal Educ Behav. 2009;36:24–8.

Clements AL, Griswold WG, RS A, Johnston JE, Herting MM, Thorson J, et al. Low-cost air quality monitoring tools: from research to practice (a workshop summary). Sensors (Basel). 2017;17:1–20.

De Souza YG, Greenspan JS. Biobanking past, present and future: responsibilities and benefits. Aids. 2013;27:303–12.

Gonzales M, King E, Bobelu J, Ghahate D, Madrid T, Lesansee S, et al. Perspectives on biological monitoring in environmental health research: a focus group study in a native american community. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15:1–8.

Fox K. The illusion of inclusion — the “all of us” research program and indigenous peoples’ DNA. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:411–3.

Sterling RL. Genetic research among the Havasupai: a cautionary tale. Virtual Mentor. 2011;13:113–7.

Williams RL, Willging CE, Quintero G, Kalishman S, Sussman AL, Freeman WL, et al. Ethics of health research in communities: perspectives from the Southwestern United States. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8:433–9.

Buchanan DR, Miller FG. Justice and fairness in the Kennedy Krieger institute lead paint study: the ethics of public health research on less expensive, less effective interventions. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:781–7.

DeLemos J, Rock T, Brugge D, Slagowski N, Manning T, Lewis J. Lessons from the Navajo: assistance with environmental data collection ensures cultural humility and data relevance. Prog Comunity Heal Partnersh. 2007;1:321–6.

Johnston JE, Lopez m, Gribble MO, Gutschow W, Austin C, Arora M. A collaborative approach to assess legacy pollution in communities near a lead–acid battery smelter: the “Truth Fairy” project. Heal Educ Behav. 2019;46:71S–80S.

Johnston JE, Franklin M, Roh H, Austin C, Arora M. Lead and arsenic in shed deciduous teeth of children living near a lead-acid battery smelter. Environ Sci Technol. 2019;53:6000–6.

Finn S, Herne M, Castille D. The value of traditional ecological knowledge for the environmental health sciences and biomedical research. Environ Health Perspect. 2017;125:1–10.

Isaac G, Finn S, Joe JR, Hoover E, Gone JP, Lefthand-Begay C, et al. Native American perspectives on health and traditional ecological knowledge. Environ Health Perspect. 2019;126:125002.

Inventionland Institute. Co-learning in education works wonders for future generatons. 2018. https://inventionlandinstitute.com/co-learning-in-education .

Garrison NA. Genomic justice for native Americans: impact of the Havasupai case on genetic research. Sci Technol Hum Values. 2013;38:201–23.

Skloot R. The immortal life of Henrietta lacks. Broadway Paperbacks: New York, NY. 2017.

Claw KG, Anderson MZ, Begay RL, Tsosie KS, Fox K, Garrison NA. A framework for enhancing ethical genomic research with Indigenous communities. Nat Commun. 2018;9:2957.

Tsosie KS, Yracheta JM, Kolopenuk J, Smith RWA. Indigenous data sovereignties and data sharing in biological anthropology. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2021;174:183–6.

Donatuto J, Grossman EE, Konovsky J, Grossman S, Campbell LW. Indigenous community health and climate change: integrating biophysical and social science indicators. Coast Manag. 2014;42:355–73.

Russo Carroll S, Rodriquez-Lonebear D, Martinez A. Indigenous data governance: strategies from United States native nations. Data Sci J. 2019;18:1–15.

Wilson SM, Wilson OR, Heaney CD, Cooper J. Use of EPA collaborative problem-solving model to obtain environmental justice in North Carolina. Prog Community Heal Partnerships Res Educ Action. 2007;1:327–37.

Brody JG, Cirillo PM, Boronow KE, Havas L, Plumb M, Susmann HP, et al. Outcomes from returning individual versus only study-wide biomonitoring results in an environmental exposure study using the Digital Exposure Report-Back Interface (DERBI). Environ Health Perspect. 2021;129:1–15.

Van Horne YO, Chief K, Charley PH, Begay MG, Lothrop N, Bell ML, et al. Impacts to Diné activities with the San Juan River after the Gold King Mine Spill. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2021;31:852–66.

Nolan JES, Coker ES, Ward BR, Williamson YA, Harley KG. “Freedom to Breathe”: Youth Participatory Action Research (YPAR) to investigate air pollution inequities in Richmond, CA. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:1–18.

Schulte PA. The epidemiologic basis for the notification of subjects of cohort studies. Am J Epidemiol. 1985;121:351–61.

Morello-Frosch R, Brody JG, Brown P, Altman RG, Rudel RA, Pérez C. Toxic ignorance and right-to-know in biomonitoring results communication: a survey of scientists and study participants. Environ Heal A Glob Access Sci Source. 2009;8:1–13.

Ohayon JL, Cousins E, Brown P, Morello-Frosch R, Brody JG. Researcher and institutional review board perspectives on the benefits and challenges of reporting back biomonitoring and environmental exposure results. Environ Res Elsevier. 2017;153:140–9.

Morello-Frosch R, Varshavsky J, Liboiron M, Brown P, Brody JG. Communicating results in post-Belmont era biomonitoring studies: lessons from genetics and neuroimaging research. Environ Res Elsevier. 2015;136:363–72.

Code C. Health & Safety Code Section. 2019;105443. https://codes.findlaw.com/ca/health-and-safety-code/hsc-sect-105443.html .

Trushna T, Diwan V, Nandi SS, Aher SB, Tiwari RR, Sabde YD. A mixed-methods community-based participatory research to explore stakeholder’s perspectives and to quantify the effect of crop residue burning on air and human health in Central India: study protocol. BMC Public Health. 2020;20:1–13.

Schollaert C, Alvarez M, Gillooly S, Tomsho K, Bongiovanni R, Chacker S, et al. Reporting results of a community-based in-home exposure monitoring study: developing methods and materials. Prog Community Heal Partnersh Res Educ Action. 2021;15:117–25.

Moll LC, Cathy A, Neff D, Gonzale N. Funds of knowledge for teaching: using a qualitative approach to connect homes and classrooms. Theory Pract. 1992;31:132–41.

Fowlie M, Walker R, Wooley D. Climate policy, environmental justice, and local air pollution. Econ. Stud. Brookings. 2020.

California Air Resources Board. Community Air Protection Program. 2020. https://ww2.arb.ca.gov/capp .

Tazewell S. Using a funds of knowledge approach to engage diverse cohorts through active and personally relevant learning BT. In: Crimmins G, editor. Strategies for supporting inclusion and diversity in the academy: higher education, aspiration and inequality. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2020. p. 247–66. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-43593-6_13 .

Wing S. Whose epidemiology, whose health? Int J Heal Serv. 1998;28:241–52.

Ruiz D, Becerra M, Jagai JS, Ard K, Sargis RM. Disparities in environmental exposures to endocrine-disrupting chemicals and diabetes risk in vulnerable populations. Diabetes Care. 2018;41:193–205.

van Woerden I, Bruening M, Montresor-López J, Payne-Sturges DC. Trends and disparities in urinary BPA concentrations among U.S. emerging adults. Environ Res. 2019;176:108515.

Rose M, Bennett DH, Bergman A, Fängström B, Pessah IN, Hertz-Picciotto I. PBDEs in 2-5 year-old children from California and associations with diet and indoor environment. Environ Sci Technol. 2010;44:2648–53.

Zota AR, Rudel RA, Morello-Frosch RA, Brody JG. Elevated house dust and serum concentrations of PBDEs in california: unintended consequences of furniture flammability standards? Environ Sci Technol. 2008;43:2661–2.

Senier L, Brown P, Shostak S, Hanna B. The socio-exposome: advancing exposure science and environmental justice in a post-genomic era. Environ Sociol. 2017;3:107–21.

Nwanaji-Enwerem JC, Jackson CL, Ottinger MA, Cardenas A, James KA, Malecki KMC, et al. Adopting a “compound” exposome approach in environmental aging biomarker research: a call to action for advancing racial health equity. Environ Health Perspect. 2021;129:1–8.

Bullard RD, Dixie DI. Race, class, and environmental quality. Westview Press: New York, NY. 2000.

Collins TW, Grineski SE, Morales DX. Environmental injustice and sexual minority health disparities: a national study of inequitable health risks from air pollution among same-sex partners. Soc Sci Med. 2017;191:38–47.

Jampel C. Intersections of disability justice, racial justice and environmental justice. Environ Sociol Routledge. 2018;4:122–35.

Download references

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge that we reside on the stolen land of Indigenous People and we acknowledge the struggles of our ancestors who came before us. Moving forward we encourage that a portion of honorarium fees received for speaking on topics belonging to the community should be re-invested in programs that promote equitable health initiatives. The following scientists contributed to this framework: Sa Liu, Jon Levy, Pallavi Pant, Ryan G. Sinclair.

YOVH is supported by a Diversity Supplement through the National Institutes of Health under R01ES029598-03S1. CSA is supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development of the National Institutes of Health under T32HD049311. LQA is supported in part by a NHLBI Career Development Award (K01HL138124). PIB is supported by the National Institutes of Health under P30ES006694. JEJ is supported by the National Institutes of Health under P30ES006694. MG is supported by NIH/NIEHS P50ES026102, NIH/NIEHS P42 ES025589, USEPA #83615701. The publication’s contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health, or the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

Author information

These authors contributed equally: Yoshira Ornelas Van Horne, Cecilia S. Alcala.

These authors jointly supervised this work: Lesliam Quirós-Alcalá, Paloma I. Beamer

Authors and Affiliations

Department of Population and Public Health Sciences, Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California, 2001 N. Soto Street, Los Angeles, CA, 90032, USA

Yoshira Ornelas Van Horne & Jill E. Johnston

Department of Environmental Medicine and Public Health, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, 17 East 102 Street, New York, NY, 10029, USA

Cecilia S. Alcala

School of Public Health & Health Sciences, University of Massachusetts Amherst, 686 North Pleasant Street, Room 175, Amherst, MA, 01003, USA

Richard E. Peltier

School of Public Health, San Diego State University, 5500 Campanile Dr., San Diego, CA, 92182, USA

Penelope J. E. Quintana

Department of Environmental & Occupational Health Sciences, School of Public Health, University of Washington, Roosevelt One Building, 4225 Roosevelt Way NE, Suite 100, Seattle, WA, 98195, USA

Edmund Seto

Department of Internal Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, MSC10 5550 Epidemiology, Albuquerque, NM, 87111, USA

Melissa Gonzales

Environmental Health Coalition, National City, CA, USA

Lupita D. Montoya

Department of Environmental Health and Engineering, Bloomberg School of Public Health, Johns Hopkins University, 615N. Wolfe Street, Baltimore, MD, 21205, USA

Lesliam Quirós-Alcalá

Department of Community, Environment and Policy, Mel and Enid Zuckerman College of Public Health, University of Arizona, 1295N. Martin Ave., Tucson, AZ, 85724, USA

Paloma I. Beamer

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

YOVH and CSA finalized the tables, figures, and led the writing of the paper for publication. REP, PJEQ, ES, MG, JEJ, and LDM contributed to the first draft. SL, JL, PP, and RGS provided comments and suggestions to the first draft. PIB, LQA, and YOVH jointly conceptualized the idea. All authors contributed to the writing and editing of the paper and read and approved the final paper.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Yoshira Ornelas Van Horne .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

YOVH, LQA, and PIB are editorial board members of JESEE. REP is deputy editor of JESEE. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Van Horne, Y.O., Alcala, C.S., Peltier, R.E. et al. An applied environmental justice framework for exposure science. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol 33 , 1–11 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41370-022-00422-z

Download citation

Received : 06 August 2021

Revised : 08 February 2022

Accepted : 10 February 2022

Published : 08 March 2022

Issue Date : January 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41370-022-00422-z

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Environmental justice

- Marginalized communities

- Health studies

- Exposure science

- Environmental health

This article is cited by

Can an evidence-based mental health intervention be implemented into preexisting home visiting programs using implementation facilitation study protocol for a three variable implementation effectiveness context hybrid trial.

- Elissa Z. Faro

- DeShauna Jones

- Kelli Ryckman

Implementation Science (2024)

- Lindsay W. Stanek

- Wayne E. Cascio

- Elaine A. Cohen Hubal

Journal of Exposure Science & Environmental Epidemiology (2024)

More extremely hot days, more heat exposure and fewer cooling options for people of color in Connecticut, U.S.

- Shijuan Chen

- Karen C. Seto

npj Urban Sustainability (2024)

Unprivileged groups are less served by green cooling services in major European urban areas

- Alby Duarte Rocha

- Stenka Vulova

- Birgit Kleinschmit

Nature Cities (2024)

Qualitative and mixed methods: informing and enhancing exposure science

- Denise Moreno Ramírez

- Ashby Lavelle Sachs

- Christine C. Ekenga

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

IMAGES

VIDEO