Stating the Obvious: Writing Assumptions, Limitations, and Delimitations

During the process of writing your thesis or dissertation, you might suddenly realize that your research has inherent flaws. Don’t worry! Virtually all projects contain restrictions to your research. However, being able to recognize and accurately describe these problems is the difference between a true researcher and a grade-school kid with a science-fair project. Concerns with truthful responding, access to participants, and survey instruments are just a few of examples of restrictions on your research. In the following sections, the differences among delimitations, limitations, and assumptions of a dissertation will be clarified.

Delimitations

Delimitations are the definitions you set as the boundaries of your own thesis or dissertation, so delimitations are in your control. Delimitations are set so that your goals do not become impossibly large to complete. Examples of delimitations include objectives, research questions, variables, theoretical objectives that you have adopted, and populations chosen as targets to study. When you are stating your delimitations, clearly inform readers why you chose this course of study. The answer might simply be that you were curious about the topic and/or wanted to improve standards of a professional field by revealing certain findings. In any case, you should clearly list the other options available and the reasons why you did not choose these options immediately after you list your delimitations. You might have avoided these options for reasons of practicality, interest, or relativity to the study at hand. For example, you might have only studied Hispanic mothers because they have the highest rate of obese babies. Delimitations are often strongly related to your theory and research questions. If you were researching whether there are different parenting styles between unmarried Asian, Caucasian, African American, and Hispanic women, then a delimitation of your study would be the inclusion of only participants with those demographics and the exclusion of participants from other demographics such as men, married women, and all other ethnicities of single women (inclusion and exclusion criteria). A further delimitation might be that you only included closed-ended Likert scale responses in the survey, rather than including additional open-ended responses, which might make some people more willing to take and complete your survey. Remember that delimitations are not good or bad. They are simply a detailed description of the scope of interest for your study as it relates to the research design. Don’t forget to describe the philosophical framework you used throughout your study, which also delimits your study.

Limitations

Limitations of a dissertation are potential weaknesses in your study that are mostly out of your control, given limited funding, choice of research design, statistical model constraints, or other factors. In addition, a limitation is a restriction on your study that cannot be reasonably dismissed and can affect your design and results. Do not worry about limitations because limitations affect virtually all research projects, as well as most things in life. Even when you are going to your favorite restaurant, you are limited by the menu choices. If you went to a restaurant that had a menu that you were craving, you might not receive the service, price, or location that makes you enjoy your favorite restaurant. If you studied participants’ responses to a survey, you might be limited in your abilities to gain the exact type or geographic scope of participants you wanted. The people whom you managed to get to take your survey may not truly be a random sample, which is also a limitation. If you used a common test for data findings, your results are limited by the reliability of the test. If your study was limited to a certain amount of time, your results are affected by the operations of society during that time period (e.g., economy, social trends). It is important for you to remember that limitations of a dissertation are often not something that can be solved by the researcher. Also, remember that whatever limits you also limits other researchers, whether they are the largest medical research companies or consumer habits corporations. Certain kinds of limitations are often associated with the analytical approach you take in your research, too. For example, some qualitative methods like heuristics or phenomenology do not lend themselves well to replicability. Also, most of the commonly used quantitative statistical models can only determine correlation, but not causation.

Assumptions

Assumptions are things that are accepted as true, or at least plausible, by researchers and peers who will read your dissertation or thesis. In other words, any scholar reading your paper will assume that certain aspects of your study is true given your population, statistical test, research design, or other delimitations. For example, if you tell your friend that your favorite restaurant is an Italian place, your friend will assume that you don’t go there for the sushi. It’s assumed that you go there to eat Italian food. Because most assumptions are not discussed in-text, assumptions that are discussed in-text are discussed in the context of the limitations of your study, which is typically in the discussion section. This is important, because both assumptions and limitations affect the inferences you can draw from your study. One of the more common assumptions made in survey research is the assumption of honesty and truthful responses. However, for certain sensitive questions this assumption may be more difficult to accept, in which case it would be described as a limitation of the study. For example, asking people to report their criminal behavior in a survey may not be as reliable as asking people to report their eating habits. It is important to remember that your limitations and assumptions should not contradict one another. For instance, if you state that generalizability is a limitation of your study given that your sample was limited to one city in the United States, then you should not claim generalizability to the United States population as an assumption of your study. Statistical models in quantitative research designs are accompanied with assumptions as well, some more strict than others. These assumptions generally refer to the characteristics of the data, such as distributions, correlational trends, and variable type, just to name a few. Violating these assumptions can lead to drastically invalid results, though this often depends on sample size and other considerations.

Click here to cancel reply.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Copyright © 2024 PhDStudent.com. All rights reserved. Designed by Divergent Web Solutions, LLC .

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

5.1 Assumptions underlying research

Learning objectives.

Learners will be able to…

- Ground your research project and working question in the philosophical assumptions of social science

- Define the terms ‘ ontology ‘ and ‘ epistemology ‘ and explain how they relate to quantitative and qualitative research methods

Pre-awareness check (Knowledge)

Thinking back on your practice experience, what types of things were dependent on a person’s own truth and more subjective? What types of things would you consider irrefutable truths and more objective?

Last chapter, we reviewed the ethical commitment that social work researchers have to protect the people and communities impacted by their research. Answering the practical questions of harm, conflicts of interest, and other ethical issues will provide clear foundation of what you can and cannot do as part of your research project. In this chapter, we will transition from the real world to the conceptual world. Together, we will discover and explore the theoretical and philosophical foundations of your project. You should complete this chapter with a better sense of how theoretical and philosophical concepts help you answer your working question, and in turn, how theory and philosophy will affect the research project you design.

Embrace philosophy

The single biggest barrier to engaging with philosophy of science, at least according to some of my students, is the word philosophy. I had one student who told me that as soon as that word came up, she tuned out because she thought it was above her head. As we discussed in Chapter 1, some students already feel like research methods is too complex of a topic, and asking them to engage with philosophical concepts within research is like asking them to tap dance while wearing ice skates.

For those students, I would first answer that this chapter is my favorite one to write because it was the most impactful for me to learn during my MSW program. Finding my theoretical and philosophical home was important for me to develop as a clinician and a researcher. Following our advice in Chapter 2, you’ve hopefully chosen a topic that is important to your interests as a social work practitioner, and consider this chapter an opportunity to find your personal roots in addition to revising your working question and designing your research study.

Exploring theoretical and philosophical questions will cause your working question and research project to become clearer. Consider this chapter as something similar to getting a nice outfit for a fancy occasion. You have to try on a lot of different theories and philosophies before you find the one that fits with what you’re going for. There’s no right way to try on clothes, and there’s no one right theory or philosophy for your project. You might find a good fit with the first one you’ve tried on, or it might take a few different outfits. You have to find ideas that make sense together because they fit with how you think about your topic and how you should study it.

As you read this section, try to think about which assumptions feel right for your working question and research project. Which assumptions match what you think and believe about your topic? The goal is not to find the “right” answer, but to develop your conceptual understanding of your research topic by finding the right theoretical and philosophical fit.

Theoretical and philosophical fluency

In addition to self-discovery, theoretical and philosophical fluency is a skill that social workers must possess in order to engage in social justice work. That’s because theory and philosophy help sharpen your perceptions of the social world. Just as social workers use empirical data to support their work, they also use theoretical and philosophical foundations. More importantly, theory and philosophy help social workers build heuristics that can help identify the fundamental assumptions at the heart of social conflict and social problems. They alert you to the patterns in the underlying assumptions that different people make and how those assumptions shape their worldview, what they view as true, and what they hope to accomplish. In the next section, we will review feminist and other critical perspectives on research, and they should help inform you of how assumptions about research can reinforce existing oppression.

Understanding these deeper structures is a true gift of social work research. Because we acknowledge the usefulness and truth value of multiple philosophies and worldviews contained in this chapter, we can arrive at a deeper and more nuanced understanding of the social world. Methods can be closely associated with particular worldviews or ideologies. There are necessarily philosophical and theoretical aspects to this, and this can be intimidating at times, but it’s important to critically engage with these questions to improve the quality of research.

Building your ice float

Although it may not seem like it right now, your project will develop a from a strong connection to previous theoretical and philosophical ideas about your topic. It’s likely you already have some (perhaps unstated) philosophical or theoretical ideas that undergird your thinking on the topic. Moreover, the philosophical questions we review here should inform how you understand different theories and practice modalities in social work, as they deal with the bedrock questions about science and human knowledge.

Before we can dive into philosophy, we need to recall our conversation from Chapter 1 about objective truth and subjective truths. Let’s test your knowledge with a quick example. Is crime on the rise in the United States? A recent Five Thirty Eight article highlights the disparity between historical trends on crime that are at or near their lowest in the thirty years with broad perceptions by the public that crime is on the rise (Koerth & Thomson-DeVeaux, 2020). [1] Social workers skilled at research can marshal objective facts, much like the authors do, to demonstrate that people’s perceptions are not based on a rational interpretation of the world. Of course, that is not where our work ends. Subjective facts might seek to decenter this narrative of ever-increasing crime, deconstruct is racist and oppressive origins, or simply document how that narrative shapes how individuals and communities conceptualize their world.

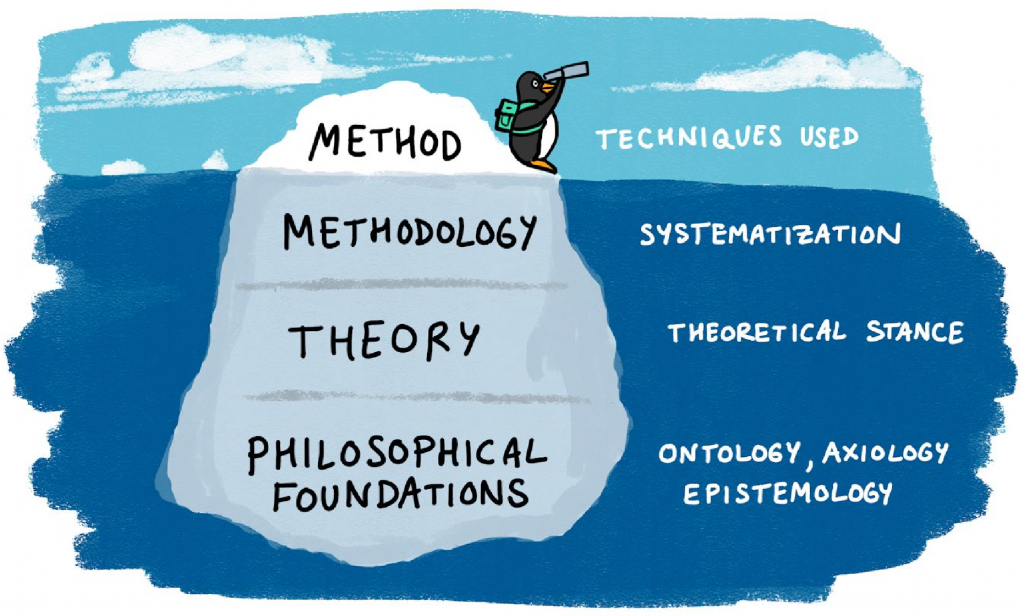

Objective does not mean right, and subjective does not mean wrong. Researchers must understand what kind of truth they are searching for so they can choose a theory(ies), develop a theoretical framework (in quantitative research), select an appropriate methodology, and make sure the research question(s) matches them all. As we discussed in Chapter 1, researchers seeking objective truth (one of the philosophical foundations at the bottom of Figure 5.1) often employ quantitative methods (one of the methods at the top of Figure 5.1). Similarly, researchers seeking subjective truths (again, at the bottom of Figure 5.1) often employ qualitative methods (at the top of Figure 5.1). This chapter is about the connective tissue, and by the time you are done reading, you should have a first draft of a theoretical and philosophical (a.k.a. paradigmatic) framework for your study.

Ontology: Assumptions about what is real and true

In section 1.2, we reviewed the two types of truth that social work researchers seek— objective truth and subjective truths —and linked these with the methods—quantitative and qualitative—that researchers use to study the world. If those ideas aren’t fresh in your mind, you may want to navigate back to that section for an introduction.

These two types of truth rely on different assumptions about what is real in the social world—i.e., they have a different ontology . Ontology refers to the study of being (literally, it means “rational discourse about being”). In philosophy, basic questions about existence are typically posed as ontological, e.g.:

- What is there?

- What types of things are there?

- How can we describe existence?

- What kind of categories can things go into?

- Are the categories of existence hierarchical?

Objective vs. subjective ontologies

At first, it may seem silly to question whether the phenomena we encounter in the social world are real. Of course you exist, your thoughts exist, your computer exists, and your friends exist. You can see them with your eyes. This is the ontological framework of realism , which simply means that the concepts we talk about in science exist independent of observation (Burrell & Morgan, 1979). [2] Obviously, when we close our eyes, the universe does not disappear. You may be familiar with the philosophical conundrum: “If a tree falls in a forest and no one is around to hear it, does it make a sound?”

The natural sciences, like physics and biology, also generally rely on the assumption of realism. Lone trees falling make a sound. We assume that gravity and the rest of physics are there, even when no one is there to observe them. Mitochondria are easy to spot with a powerful microscope, and we can observe and theorize about their function in a cell. The gravitational force is invisible, but clearly apparent from observable facts, such as watching an apple fall from a tree. Of course, our theories about gravity have changed over the years. Improvements were made when observations could not be correctly explained using existing theories and new theories emerged that provided a better explanation of the data.

As we discussed in section 1.2, culture-bound syndromes are an excellent example of where you might come to question realism. Of course, from a Western perspective as researchers in the United States, we think that the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) classification of mental health disorders is real and that these culture-bound syndromes are aberrations from the norm. But what about if you were a person from Korea experiencing Hwabyeong? Wouldn’t you consider the Western diagnosis of somatization disorder to be incorrect or incomplete? This conflict raises the question–do either Hwabyeong or DSM diagnoses like post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) really exist at all…or are they just social constructs that only exist in our minds?

If your answer is “no, they do not exist,” you are adopting the ontology of anti-realism ( or relativism ), or the idea that social concepts do not exist outside of human thought. Unlike the realists who seek a single, universal truth, the anti-realists perceive a sea of truths, created and shared within a social and cultural context. Unlike objective truth, which is true for all, subjective truths will vary based on who you are observing and the context in which you are observing them. The beliefs, opinions, and preferences of people are actually truths that social scientists measure and describe. Additionally, subjective truths do not exist independent of human observation because they are the product of the human mind. We negotiate what is true in the social world through language, arriving at a consensus and engaging in debate within our socio-cultural context.

These theoretical assumptions should sound familiar if you’ve studied social constructivism or symbolic interactionism in MSW courses, most likely in human behavior in the social environment (HBSE). [3] From an anti-realist perspective, what distinguishes the social sciences from natural sciences is human thought. When we try to conceptualize trauma from an anti-realist perspective, we must pay attention to the feelings, opinions, and stories in people’s minds. In their most radical formulations, anti-realists propose that these feelings and stories are all that truly exist.

What happens when a situation is incorrectly interpreted? Certainly, who is correct about what is a bit subjective. It depends on who you ask. Even if you can determine whether a person is actually incorrect, they think they are right. Thus, what may not be objectively true for everyone is nevertheless true to the individual interpreting the situation. Furthermore, they act on the assumption that they are right. We all do. Much of our behaviors and interactions are a manifestation of our personal subjective truth. In this sense, even incorrect interpretations are truths, even though they are true only to one person or a group of misinformed people. This leads us to question whether the social concepts we think about really exist. For researchers using subjective ontologies, they might only exist in our minds; whereas, researchers who use objective ontologies which assume these concepts exist independent of thought.

How do we resolve this dichotomy? As social workers, we know that often times what appears to be an either/or situation is actually a both/and situation. Let’s take the example of trauma. There is clearly an objective thing called trauma. We can draw out objective facts about trauma and how it interacts with other concepts in the social world such as family relationships and mental health. However, that understanding is always bound within a specific cultural and historical context. Moreover, each person’s individual experience and conceptualization of trauma is also true. Much like a client who tells you their truth through their stories and reflections, when a participant in a research study tells you what their trauma means to them, it is real even though only they experience and know it that way. By using both objective and subjective analytic lenses, we can explore different aspects of trauma—what it means to everyone, always, everywhere, and what is means to one person or group of people, in a specific place and time.

Epistemology: Assumptions about how we know things

Having discussed what is true, we can proceed to the next natural question—how can we come to know what is real and true? This is epistemology . Epistemology is derived from the Ancient Greek epistēmē which refers to systematic or reliable knowledge (as opposed to doxa, or “belief”). Basically, it means “rational discourse about knowledge,” and the focus is the study of knowledge and methods used to generate knowledge. Epistemology has a history as long as philosophy, and lies at the foundation of both scientific and philosophical knowledge.

Epistemological questions include:

- What is knowledge?

- How can we claim to know anything at all?

- What does it mean to know something?

- What makes a belief justified?

- What is the relationship between the knower and what can be known?

While these philosophical questions can seem far removed from real-world interaction, thinking about these kinds of questions in the context of research helps you target your inquiry by informing your methods and helping you revise your working question. Epistemology is closely connected to method as they are both concerned with how to create and validate knowledge. Research methods are essentially epistemologies – by following a certain process we support our claim to know about the things we have been researching. Inappropriate or poorly followed methods can undermine claims to have produced new knowledge or discovered a new truth. This can have implications for future studies that build on the data and/or conceptual framework used.

Research methods can be thought of as essentially stripped down, purpose-specific epistemologies. The knowledge claims that underlie the results of surveys, focus groups, and other common research designs ultimately rest on epistemological assumptions of their methods. Focus groups and other qualitative methods usually rely on subjective epistemological (and ontological) assumptions. Surveys and other quantitative methods usually rely on objective epistemological assumptions. These epistemological assumptions often entail congruent subjective or objective ontological assumptions about the ultimate questions about reality.

Objective vs. subjective epistemologies

One key consideration here is the status of ‘truth’ within a particular epistemology or research method. If, for instance, some approaches emphasize subjective knowledge and deny the possibility of an objective truth, what does this mean for choosing a research method?

We began to answer this question in Chapter 1 when we described the scientific method and objective and subjective truths. Epistemological subjectivism focuses on what people think and feel about a situation, while epistemological objectivism focuses on objective facts irrelevant to our interpretation of a situation (Lin, 2015). [4]

While there are many important questions about epistemology to ask (e.g., “How can I be sure of what I know?” or “What can I not know?” see Willis, 2007 [5] for more), from a pragmatic perspective most relevant epistemological question in the social sciences is whether truth is better accessed using numerical data or words and performances. Generally, scientists approaching research with an objective epistemology (and realist ontology) will use quantitative methods to arrive at scientific truth. Quantitative methods examine numerical data to precisely describe and predict elements of the social world. For example, while people can have different definitions for poverty, an objective measurement such as an annual income of “less than $25,100 for a family of four” provides a precise measurement that can be compared to incomes from all other people in any society from any time period, and refers to real quantities of money that exist in the world. Mathematical relationships are uniquely useful in that they allow comparisons across individuals as well as time and space. In this book, we will review the most common designs used in quantitative research: surveys and experiments. These types of studies usually rely on the epistemological assumption that mathematics can represent the phenomena and relationships we observe in the social world.

Although mathematical relationships are useful, they are limited in what they can tell you. While you can use quantitative methods to measure individuals’ experiences and thought processes, you will miss the story behind the numbers. To analyze stories scientifically, we need to examine their expression in interviews, journal entries, performances, and other cultural artifacts using qualitative methods . Because social science studies human interaction and the reality we all create and share in our heads, subjectivists focus on language and other ways we communicate our inner experience. Qualitative methods allow us to scientifically investigate language and other forms of expression—to pursue research questions that explore the words people write and speak. This is consistent with epistemological subjectivism’s focus on individual and shared experiences, interpretations, and stories.

It is important to note that qualitative methods are entirely compatible with seeking objective truth. Approaching qualitative analysis with a more objective perspective, we look simply at what was said and examine its surface-level meaning. If a person says they brought their kids to school that day, then that is what is true. A researcher seeking subjective truth may focus on how the person says the words—their tone of voice, facial expressions, metaphors, and so forth. By focusing on these things, the researcher can understand what it meant to the person to say they dropped their kids off at school. Perhaps in describing dropping their children off at school, the person thought of their parents doing the same thing. In this way, subjective truths are deeper, more personalized, and difficult to generalize.

Putting it all together

As you might guess by the structure of the next two parts of this textbook, the distinction between quantitative and qualitative is important. Because of the distinct philosophical assumptions of objectivity and subjectivity, it will inform how you define the concepts in your research question, how you measure them, and how you gather and interpret your raw data. You certainly do not need to have a final answer right now! But stop for a minute and think about which approach feels right so far. In the next section, we will consider another set of philosophical assumptions that relate to ethics and the role of research in achieving social justice.

Key Takeaways

- Philosophers of science disagree on the basic tenets of what is true and how we come to know what is true.

- Researchers searching for objective truth will likely have a different research design, and methods than researchers searching for subjective truths.

- These differences are due to different assumptions about what is real and true (ontology) and how we can come to understand what is real and true (epistemology).

TRACK 1 (IF YOU ARE CREATING A RESEARCH PROPOSAL FOR THIS CLASS):

Does an objective or subjective epistemological/ontological framework make the most sense for your research project?

- Are you more concerned with how people think and feel about your topic, their subjective truths—more specific to the time and place of your project?

- Or are you more concerned with objective truth, so that your results might generalize to populations beyond the ones in your study?

Using your answer to the above question, describe how either quantitative or qualitative methods make the most sense for your project.

TRACK 2 (IF YOU AREN’T CREATING A RESEARCH PROPOSAL FOR THIS CLASS):

You are interested in researching bullying among school-aged children, and how this impacts students’ academic success.

- If you are using an objective epistemological/ontological framework, what types of research questions might you ask?

- If you are using a subjective epistemological/ontological framework, what types of research questions might you ask?

- Koerth, M. & Thomson-DeVeaux, A. (2020, August 3). Many Americans are convinced crime is rising in the U.S. They're wrong. FiveThirtyEight . Retrieved from: https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/many-americans-are-convinced-crime-is-rising-in-the-u-s-theyre-wrong ↵

- Burrell, G. & Morgan, G. (1979). Sociological paradigms and organizational analysis . Routledge. ↵

- Here are links to two HBSE open textbooks, if you are unfamiliar with social work theories. https://uark.pressbooks.pub/hbse1/ and https://uark.pressbooks.pub/humanbehaviorandthesocialenvironment2/ ↵

- Lin, C. T. (2016). A critique of epistemic subjectivity. Philosophia, 44 (3), 915-920. ↵

- Wills, J. W. (2007). World views, paradigms and the practice of social science research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. ↵

a single truth, observed without bias, that is universally applicable

one truth among many, bound within a social and cultural context

assumptions about what is real and true

assumptions about how we come to know what is real and true

quantitative methods examine numerical data to precisely describe and predict elements of the social world

qualitative methods interpret language and behavior to understand the world from the perspectives of other people

Doctoral Research Methods in Social Work Copyright © by Mavs Open Press. All Rights Reserved.

Share This Book

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Research Design Considerations

Sarah wright , phd, mba, bridget c o'brien , phd, laura nimmon , phd, marcus law , md, mba, med, maria mylopoulos , phd.

- Author information

- Copyright and License information

Corresponding author: Sarah Wright, PhD, MBA, Toronto East General Hospital, 825 Coxwell Avenue, Toronto, ON M4C 3E7 Canada, [email protected]

Editor's Note: The online version of this article contains references and resources for further reading and the authors' professional information.

The Challenge

“I'd really like to do a survey” or “Let's conduct some interviews” might sound like reasonable starting points for a research project. However, it is crucial that researchers examine their philosophical assumptions and those underpinning their research questions before selecting data collection methods. Philosophical assumptions relate to ontology, or the nature of reality, and epistemology, the nature of knowledge. Alignment of the researcher's worldview (ie, ontology and epistemology) with methodology (research approach) and methods (specific data collection, analysis, and interpretation tools) is key to quality research design. This Rip Out will explain philosophical differences between quantitative and qualitative research designs and how they affect definitions of rigorous research.

What Is Known

Worldviews offer different beliefs about what can be known and how it can be known, thereby shaping the types of research questions that are asked, the research approach taken, and ultimately, the data collection and analytic methods used. Ontology refers to the question of “What can we know?” Ontological viewpoints can be placed on a continuum: researchers at one end believe that an observable reality exists independent of our knowledge of it, while at the other end, researchers believe that reality is subjective and constructed, with no universal “truth” to be discovered. 1,2 Epistemology refers to the question of “How can we know?” 3 Epistemological positions also can be placed on a continuum, influenced by the researcher's ontological viewpoint. For example, the positivist worldview is based on belief in an objective reality and a truth to be discovered. Therefore, knowledge is produced through objective measurements and the quantitative relationships between variables. 4 This might include measuring the difference in examination scores between groups of learners who have been exposed to 2 different teaching formats, in order to determine whether a particular teaching format influenced the resulting examination scores.

In contrast, subjectivists (also referred to as constructionists or constructivists ) are at the opposite end of the continuum, and believe there are multiple or situated realities that are constructed in particular social, cultural, institutional, and historical contexts. According to this view, knowledge is created through the exploration of beliefs, perceptions, and experiences of the world, often captured and interpreted through observation, interviews, and focus groups. A researcher with this worldview might be interested in exploring the perceptions of students exposed to the 2 teaching formats, to better understand how learning is experienced in the 2 settings. It is crucial that there is alignment between ontology (what can we know?), epistemology (how can we know it?), methodology (what approach should be used?), and data collection and analysis methods (what specific tools should be used?). 5

Key Differences in Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches

Use of theory.

Quantitative approaches generally test theory, while qualitative approaches either use theory as a lens that shapes the research design or generate new theories inductively from their data. 4

Use of Logic

Quantitative approaches often involve deductive logic, starting off with general arguments of theories and concepts that result in data points. 4 Qualitative approaches often use inductive logic or both inductive and deductive logic, start with the data, and build up to a description, theory, or explanatory model. 4

Purpose of Results

Quantitative approaches attempt to generalize findings; qualitative approaches pay specific attention to particular individuals, groups, contexts, or cultures to provide a deep understanding of a phenomenon in local context. 4

Establishing Rigor

Quantitative researchers must collect evidence of validity and reliability. Some qualitative researchers also aim to establish validity and reliability. They seek to be as objective as possible through techniques, including cross-checking and cross-validating sources during observations. 6 Other qualitative researchers have developed specific frameworks, terminology, and criteria on which qualitative research should be evaluated. 6,7 For example, the use of credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability as criteria for rigor seek to establish the accuracy, trustworthiness, and believability of the research, rather than its validity and reliability. 8 Thus, the framework of rigor you choose will depend on your chosen methodology (see “Choosing a Qualitative Research Approach” Rip Out).

View of Objectivity

A goal of quantitative research is to maintain objectivity, in other words, to reduce the influence of the researcher on data collection as much as possible. Some qualitative researchers also attempt to reduce their own influence on the research. However, others suggest that these approaches subscribe to positivistic ideals, which are inappropriate for qualitative research, 6,9,10 as researchers should not seek to eliminate the effects of their influence on the study but to understand them through reflexivity . 11 Reflexivity is an acknowledgement that, to make sense of the social world, a researcher will inevitably draw on his or her own values, norms, and concepts, which prevent a totally objective view of the social world. 12

Sampling Strategies

Quantitative research favors using large, randomly generated samples, especially if the intent of the research is to generalize to other populations. 6 Instead, qualitative research often focuses on participants who are likely to provide rich information about the study questions, known as purposive sampling . 6

How You Can Start TODAY

Consider how you can best address your research problem and what philosophical assumptions you are making.

Consider your ontological and epistemological stance by asking yourself: What can I know about the phenomenon of interest? How can I know what I want to know? W hat approach should I use and why? Answers to these questions might be relatively fixed but should be flexible enough to guide methodological choices that best suit different research problems under study. 5

Select an appropriate sampling strategy. Purposive sampling is often used in qualitative research, with a goal of finding information-rich cases, not to generalize. 6

Be reflexive: Examine the ways in which your history, education, experiences, and worldviews have affected the research questions you have selected and your data collection methods, analyses, and writing. 13

How You Can Start TODAY—An Example

Let's assume that you want to know about resident learning on a particular clinical rotation. Your initial thought is to use end-of-rotation assessment scores as a way to measure learning. However, these assessments cannot tell you how or why residents are learning. While you cannot know for sure that residents are learning, consider what you can know—resident perceptions of their learning experiences on this rotation.

Next, you consider how to go about collecting this data—you could ask residents about their experiences in interviews or watch them in their natural settings. Since you would like to develop a theory of resident learning in clinical settings, you decide to use grounded theory as a methodology, as you believe asking residents about their experience using in-depth interviews is the best way for you to elicit the information you are seeking. You should also do more research on grounded theory by consulting related resources, and you will discover that grounded theory requires theoretical sampling. 14,15 You also decide to use the end-of-rotation assessment scores to help select your sample.

Since you want to know how and why students learn, you decide to sample extreme cases of students who have performed well and poorly on the end-of-rotation assessments. You think about how your background influences your standpoint about the research question: Were you ever a resident? How did you score on your end-of-rotation assessments? Did you feel this was an accurate representation of your learning? Are you a clinical faculty member now? Did your rotations prepare you well for this role? How does your history shape the way you view the problem? Seek to challenge, elaborate, and refine your assumptions throughout the research.

As you proceed with the interviews, they trigger further questions, and you then decide to conduct interviews with faculty members to get a more complete picture of the process of learning in this particular resident clinical rotation.

What You Can Do LONG TERM

Familiarize yourself with published guides on conducting and evaluating qualitative research. 5,16–18 There is no one-size-fits-all formula for qualitative research. However, there are techniques for conducting your research in a way that stays true to the traditions of qualitative research.

Consider the reporting style of your results. For some research approaches, it would be inappropriate to quantify results through frequency or numerical counts. 19 In this case, instead of saying “5 respondents reported X,” you might consider “respondents who reported X described Y.”

Review the conventions and writing styles of articles published with a methodological approach similar to the one you are considering. If appropriate, consider using a reflexive writing style to demonstrate understanding of your own role in shaping the research. 6

Supplementary Material

Associated data.

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

- View on publisher site

- PDF (112.3 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

Assumptions underlying quantitative and qualitative research: Implications for institutional research

- Published: October 1995

- Volume 36 , pages 535–562, ( 1995 )

Cite this article

- Russel S. Hathaway 1

2907 Accesses

16 Citations

Explore all metrics

For institutional researchers, the choice to use a quantitative or qualitative approach to research is dictated by time, money, resources, and staff. Frequently, the choice to use one or the other approach is made at the method level. Choices made at this level generally have rigor, but ignore the underlying philosophical assumptions structuring beliefs about methodology, knowledge, and reality. When choosing a method, institutional researchers also choose what they believe to be knowledge, reality, and the correct method to measure both. The purpose of this paper is to clarify and explore the assumptions underlying quantitative and qualitative research. The reason for highlighting the assumptions is to increase the general level of understanding and appreciation of epistemological issues in institutional research. Articulation of these assumptions should foster greater awareness of the appropriateness of different kinds of knowledge for different purposes.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Beyond qualitative/quantitative structuralism: the positivist qualitative research and the paradigmatic disclaimer.

Methodological Transparency and Big Data: A Critical Comparative Analysis of Institutionalization

Qualitative Methods for Policy Analysis: Case Study Research Strategy

Allender, J. S. (1986). Educational research: A personal and social process. Review of Educational Research 56(2): 173–193.

Google Scholar

Banks, J. A. (1988). Multiethnic Education , 2nd ed. Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Bauman, Z. (1992). Intimations of Postmodernity . New York: Routledge.

Bernstein, R. J. (1976). The Restructuring of Social and Political Theory . Philadelphia: The University of Pennsylvania Press.

Bernstein, R. J. (1983). Beyond Objectivism and Relativism. Science, Hermeneutics, and Praxis . Philadelphia: The University of Pennsylvania Press.

Bohannon, T. R. (1988). Applying regression analysis to problems in institutional research. In B. D. Yancey (ed.), Applying Statistics in Institutional Research , 43–60. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, Publishers.

Bunda, M. A. (1991). Capturing the richness of student outcomes with qualitative techniques. In D. M. Fetterman (ed.), Using Qualitative Methods in Institutional Research , pp. 35–47. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, Publishers.

Cziko, G. A. (1989). Unpredictability and indeterminism in human behavior: Arguments and implications for educational research. Educational Researcher 18(3): 17–25.

Darder, A. (1991). Culture and Power in the Classroom. A Critical Foundation for Bi-cultural Education . New York: Bergin & Garvey.

Denzin, N. K. (1971). The logic of naturalistic inquiry. Social Forces 50: 166–182.

Denzin, N. K., and Y. S. Lincoln (1994) (eds.). Handbook of Qualitative Research . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

Dewey, J. (1933). How We Think . Massachusetts: D. C. Heath.

Dilthey, W. (1990). The rise of hermeneutics. In G. L. Ormiston and A. D. Schrift (eds.), The Hermeneutic Tradition. From Ast to Ricoeur (pp. 101–114). Albany: State University of New York Press.

Donmoyer, R. (1985). The rescue from relativism: Two failed attempts and an alternative strategy. Educational Researcher 14(10): 13–20.

Eisner, E. W. (1981). On the differences between scientific and artistic approaches to qualitative research. Educational Researcher 10(4): 5–9.

Eisner, E. W. (1983). Anastasia might still be alive, but the monarchy is dead. Educational Researcher 12(5): 13–14, 23–24.

Fetterman, D. M. (1991). Qualitative resource landmarks. In D. M. Fetterman (ed.), Using Qualitative Methods in Institutional Research , pp. 81–84. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, Publishers.

Fincher, C. (1985). The art and science of institutional research. In M. W. Peterson and M. Corcoran (eds.), Institutional Research in Transition , pp. 17–37. New Directions for Institutional Research. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Inc., Publishers.

Firestone, W. A. (1987). Meaning in method: The rhetoric of quantitative and qualitative research. Educational Researcher 16(7): 16–21.

Firestone, W. A. (1993). Alternative arguments for generalizing from data as applied to qualitative research. Educational Researcher 22(4): 16–23.

Flew, A. (1984). A Dictionary of Philosophy . London: The Macmillan Press Ltd.

Garrison, J. W. (1986). Some principles of postpositivistic philosophy of science. Educational Researcher 15(9): 12–18.

Geertz, C. (1973). The interpretation of Cultures . New York: Basic Books.

Giarelli, J. M., and Chambliss, J. J. (1988). Philosophy of education as qualitative inquiry. In R. R. Sherman and R. B. Webb (eds.), Qualitative Research in Education: Focus and Methods , pp. 30–43. New York: The Falmer Press.

Giroux, H. A. (1988). Schooling and the Struggle for Public Life. Critical Pedagogy in the Modern Age . Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Giroux, H. A. (1991) (ed.). Postmodernism, Feminism, and Cultural Politics . Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Gordon, E. W., F. Miller, and D. Rollock (1990). Coping with communicentric bias in knowledge production in the social sciences. Educational Researcher 19(3): 14–19.

Gore, J. M. (1993). The Struggle for Pedagogies. Critical and Feminist Discourses as Regimes of Truth . New York: Routledge.

Guba, E. (1987). What have we learned about naturalistic evaluation? Evaluation Practice 8(1): 23–43.

Guba, E., and Y. Lincoln (1981). Effective Evaluation . San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Guba, E. G., and Y. S. Lincoln (1988). Do inquiry paradigms imply inquiry methodologies? In D. M. Fetterman (ed.), Qualitative Approaches to Evaluation in Education: The Silent Scientific Revolution , pp. 89–115. New York: Praeger Publishers.

Gubrium, J. (1988). Analyzing Field Reality . Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Habermas, J. (1971). Knowledge and Human Interest . Boston, MA: Beacon.

Habermas, J. (1988). On the Logic of the Social Sciences (S. W. Nicholsen and J. A. Stark, trans.). Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Hall, E. T. (1976). Beyond Culture . New York: Doubleday.

Herriott, R. E., and W. A. Firestone (1983). Multisite qualitative policy research: Optimizing description and generalizability. Educational Researcher 12(2): 14–19.

Heyl, J. D. (1975). Paradigms in social science. Society 12(5): 61–67.

Hinkle, D. E., G. W. McLaughlin, and J. T. Austin (1988). Using log-linear models in higher education research. In B. D. Yancey (ed.), Applying statistics in Institutional Research , pp. 23–42. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, Publishers.

Howe, K. R. (1985). Two dogmas of educational research. Educational Researcher 14(8): 10–18.

Howe, K. R. (1988). Against the quantitative-qualitative incompatibility thesis or dogmas die hard. Educational Researcher 17(8): 10–16.

Hutchinson, S. A. (1988). Educational and grounded theory. In R. R. Sherman and R. B. Webb (eds.), Qualitative Research in Education: Focus and Methods , pp. 123–140. New York: The Falmer Press.

Jacob, E. (1988). Clarifying qualitative research: A focus on traditions. Educational Researcher (17(1): 16–24.

James, W. (1918). The Principles of Psychology . New York: Dover.

Jennings, L. W., and D. M. Young (1988). Forecasting methods for institutional research. In B. D. Yancey (ed.), Applying Statistics in Institutional Research , pp. 77–96. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, Publishers.

Kaplan, A. (1964). The Conduct of Inquiry . San Francisco: Chandler.

Kent, T. (1991). On the very idea of a discourse community. College Composition and Communication 42(4): 425–445.

Kirk, J., and M. L. Miller (1986). Reliability and Validity in Qualitative Research . Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

Kuhn, T. S. (1962). The structure of Scientific Revolutions . Philadelphia: The University of Pennsylvania Press.

Kuhn, T. S. (1970). The Structure of Scientific Revolutions , 2nd ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Kuhn, T. S. (1974). Second thoughts on paradigms. Reprinted in The Essential Tension: Selected Studies in Scientific Tradition and Change . Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Kvale, S. (1983). The qualitative research interview: A phenomenological and a hermeneutical mode of understanding. Journal of Phenomenological Psychology 14(2): 171–196.

Lancy, D. (1993). Qualitative Research in Education . New York: Longman.

Lather, P. 1991a). Getting Smart: Feminist Research and Pedagogy Within the Post-modern . New York: Routledge.

Lather, P. (1991b). Deconstructing/deconstructive inquiry: The politics of knowing and being known. Educational Theory 41(2): 153–173.

Lewin, K. (1951). Field Theory in Social Science . New York: Harper.

Lincoln, Y. S., and E. G. Guba (1985). Naturalistic Inquiry . Beverly Hills: Sage Publications.

Marshall, C., Y. S. Lincoln, and A. E. Austin (1991). Integrating a qualitative and quantitative assessment of the quality of academic life: Political and logistical issues. In D. M. Fetterman (ed.), Using Qualitative Methods in Institutional Research , pp. 65–80. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, Publishers.

McCracken, G. (1988). The Long Interview . Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

Merton, R. (1972). Insiders and outsiders: A chapter in the sociology of knowledge. In Varieties of Political Expression in Sociology . Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Miles, M. B., and A. M. Huberman (1984). Drawing valid meaning from qualitative data: Toward a shared craft. Educational Researcher 13(5): 20–30.

Mishler, E. G. (1986). Research Interviewing. Context and Narrative . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Moss, P. A. (1990, April). Multiple Triangulation in Impact Assessment: Setting the Context . Remarks prepared for oral presentation in P. LeMahieu (Chair), Multiple triangulation in impact assessment: The Pittsburgh discussion project experience. Symposium conducted at the annual meeting of the American Research Association, Boston, Massachusetts.

Packer, M. J., and R. B. Addison (1989). Introduction. In M. J. Packer and R. B. Addison (eds.), Entering the Circle: Hermeneutic Investigation in Psychology , pp. 13–36. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Patton, M. Q. (1980). Qualitative Evaluation Methods . Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

Peterson, M. W. (1985a). Emerging developments in postsecondary organization theory and research: Fragmentation or integration. Educational Researcher 14(3): 5–12.

Peterson, M. W. (1985b). Institutional research: An evolutionary perspective. In M. W. Peterson and M. Corcoran (eds.), Institutional Research in Transition , pp. 5–15. New Directions for Institutional Research, no. 46. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Inc., Publishers.

Peterson, M. W., and M. G. Spencer (1993). Qualitative and quantitative approaches to academic culture: Do they tell us the same thing? Higher Education: Handbook of Theory and Research , Vol. IX, pp. 344–388. New York: Agathon Press.

Phillips, D. C. (1983). After the wake: Postpositivistic educational thought. Educational Researcher 12(5); 4–12.

Pike, K. L. (1967). Language in Relation to a Unified Theory of the Structure of Human Behavior . The Hague: Mouton.

Rabinow, P., and W. M. Sullivan (1987). The interpretive turn: A second look. In P. Rabinow and W. M. Sullivan (eds.), Interpretive Social Science. A Second Look , pp. 1–30. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Rogers, C. R. (1951). Client-Centered Therapy . Boston: Houghton.

Rosenau, P. M. (1992). Post-Modernism and the Social Sciences: Insights, Inroads, and Intrusions . Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Rossman, G. B., and B. L. Wilson (1985). Numbers and words. Combining quantitative and qualitative methods in a single large-scale evaluation study. Evaluation Review 9(5): 627–643.

Runes, D. D. (1983). Dictionary of Philosophy . New York: Philosophical Library, Inc.

Schultz, A. (1967). The Phenomenology of the Social World . Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press.

Sherman, R. R., and R. B. Webb (1988). Qualitative research in education: A focus. In R. R. Sherman and R. B. Webb (eds.), Qualitative Research in Education: Focus and Methods , pp. 2–21. New York: The Falmer Press.

Shulman, L. S. (1981). Disciplines of inquiry in education: An overview. Educational Researcher 10(6): 5–12, 23.

Smith, J. K. (1983a). Quantitative versus qualitative research: An attempt to clarify the issue. Educational Researcher 12(3): 6–13.

Smith, J. K. (1983b). Quantitative versus interpretive: The problem of conducting social inquiry. In E. House (ed.), Philosophy of Evaluation , pp. 27–52. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Smith, J. K. (1984). The problem of criteria for judging interpretive inquiry. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis 6(4): 379–391.

Smith, J. K., and L. Heshusius (1986). Closing down the conversation: The end of the quantitative-qualitative debate among educational inquirers. Educational Researcher 15(1): 4–12.

Soltis, J. F. (1984). On the nature of educational research. Educational Researcher 13(10: 5–10.

Stanfield, J. H. (1985). The ethnocentric basis of social science knowledge production. In E. W. Gorden (ed.), Review of Research in Education , vol. 12, pp. 387–415. Washington, DC: American Educational Research Association.

Taylor, C. (1987). Interpretation and the science of man. In P. Rabinow and W. M. Sullivan (eds.), Interpretive Social Science. A Second Look , pp. 33–81. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Tierney, W. G. (1991). Utilizing ethnographic interviews to enhance academic decision making. In D. M. Fetterman (ed.), Using Qualitative Methods in Institutional Research , pp. 7–22. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, Publishers.

Urmson, J. O., and J. Ree (1989) (eds.). The Concise Encyclopedia of Western Philosophy and Philosophies . Boston: Unwin Hyman.

Yancey, B. D. (1988a). Exploratory data analysis methods for institutional researchers. In B. D. Yancey (ed.), Applying Statistics in Institutional Research , pp. 97–110. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, Publishers.

Yancey, B. D. (1988b). Institutional research and the classical experimental paradigm. In B. D. Yancey (ed.), Applying Statistics in Institutional Research , pp. 5–10. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, Publishers.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

The University of Michigan, 4216D School of Education Building, 48109-1259, Ann Arbor, MI

Russel S. Hathaway

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Hathaway, R.S. Assumptions underlying quantitative and qualitative research: Implications for institutional research. Res High Educ 36 , 535–562 (1995). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02208830

Download citation

Received : 23 May 1994

Issue Date : October 1995

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02208830

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Qualitative Research

- General Level

- Correct Method

- Qualitative Approach

- Great Awareness

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Assumptions in Research: Foundation, 5 Types, and Impact

An assumption is a belief, thing, or statement that is taken as true by the researcher. It is not tested in research because these statements are the cornerstone of whole research. These are universally accepted and sufficiently well demonstrated that the researcher can build on them.

They are a fundamental part of the human experience. People make them in their everyday decisions and experiences. If we do not consider these assumptions, our research will not proceed any further.

Our inferences or conclusions are often based on them, and sometimes we do not think about it critically. Nevertheless, a critical thinker pays close attention to these assumptions, recognizing that they can be flawed or misinformed. Merely presuming something’s validity doesn’t guarantee its accuracy. Just because we assume something is true doesn’t mean it is.

In research, we must think carefully about them when finding and analyzing information, but we also must think carefully about the assumptions of others. When looking at a website or a scholarly article, we should always consider the author’s assumptions, whether the author has taken them logically.

However, when one person believes one thing to be true, it may be somewhat different from what another person believes to be true. Although the well-established assumptions are firmly rooted in prior research, most of us tend to accept those assumptions that square with our own personal or professional views of the world without questioning the extent to which they have been or are capable of being verified. In addition, assumptions are not always easy to state. Seasoned researchers may not consider it seemly to admit that fact, but beginning researchers are quick to acknowledge the difficulty and to ask where the dividing line falls between assumptions and hypotheses. For example, the statement that memory loss occurs with aging may be accepted as an assumption by some but as a hypothesis for investigation by others.

Assumptions are things that are accepted as true; any scholar reading our paper will assume that certain aspects of our study are true, like population, statistical test, research design, or other delimitations. For example, if I tell my friend that the jungle is my favorite place, he will assume that I have never encountered a lion in the jungle. It’s assumed that I go there for walks and recreation. Because most assumptions are not discussed in text, assumptions that are discussed in text are discussed in the context of the limitations of our study, which is typically in the discussion section.

This is important, because both assumptions and limitations affect the inferences we can draw from your study. One prevalent assumption often made in survey research involves expecting honesty and truthful answers. However, for certain sensitive questions this assumption may be more difficult to accept, in this case it would be described as a limitation of the study.

For example, asking people to report their criminal or sexual behavior in a survey may not be as reliable as asking people to report their eating habits. It is important to remember that our limitations and assumptions should not contradict one another. For instance, if we state that generalizability is a limitation of our study given that our sample was limited to one city in Pakistan, then we should not claim generalizability to Pakistan population as an assumption of our study.

In quantitative research designs, statistical models come with accompanying assumptions, which can vary in their stringency. These assumptions typically pertain to data characteristics, including distributions, correlations, and variable types. Violating these assumptions can lead to drastically invalid results, though this often depends on sample size and other considerations.

Table of Contents

Types of assumptions, 1. universal .

These assumptions are believed to be universally accepted and considered as true by large part of society. To test these assumptions is a very difficult task.

For example: There is a super natural force which holds this whole universe.

2. Based On Theories

If a researcher is working on a theory, the assumptions used in that theory will also be the assumptions of this study.

For example: Research on atomic theory will take the assumptions of development of atomic theory.

3. Common Sense Assumptions

Some of the common sense assumptions are taken to conduct a research.

For example: Heart attack is more common in urban areas as compared to rural areas.

4. Warranted

This assumption is supported by certain evidence.

For example: Regular walk can reduce obesity.

5. Unwarranted

This assumption is not supported by evidences.

For example: God exists everywhere in this universe.

Examples in Research

- Sample is a true representative of population.

- It is a true experimental design.

- In comparison of two teaching methods, the behavior of students will be ideal and results are generalizable.

- We will receive true responses from respondents.

- During the experiment in laboratory, no hidden factors will affect the results of experiment.

- The equipment is functioning well and there is no error in equipment.

IDENTIFYING ASSUMPTION

When we make incorrect or unreasonable assumption during research, we will get false conclusions. So we should think that what assumption should be a part of thesis and what should not be. A good assumption is that which can be verified or justified. A bad one on the other hand cannot be verified or justified. The researcher must explain and give examples that the assumption made is true. For example, if the researcher is making an assumption that respondents will give honest responses to your questions, he or she must explain the data collection process and how will preserve anonymity and confidentiality to maximize the truthfulness.

DIFFERENCE BETWEEN HYPOTHESIS AND ASSUMPTION

A hypothesis is an intelligent guess which establishes relationship between variables. On the other hand, assumption is statement or belief which is taken as true without any justification. Hypothesis is tested explicitly, and assumption is tested implicitly. Hypothesis passes through the stages of verification. Assumption specifies the existence of relationship between variables while hypothesis establishes this relationship.

Hypotheses and assumption are so close to each other that sometime they create confusion. Assumption is assumed true statement without having any firm explanation behind it. Hypothesis is an assumption which is taken to be true unless proved otherwise.

Discover more from Theresearches

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Type your email…

Continue reading

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Statistical models in quantitative research designs are accompanied with assumptions as well, some more strict than others. These assumptions generally refer to the characteristics of the data, such as distributions, correlational trends, and variable type, just to name a few.

Assumptions are the cornerstones upon which research is built. Assumptions are the things that are taken for granted within a study because most people believe them to be true, but they are crucial to research because they directly influence what kind of inferences can be reasonably drawn.

They alert you to the patterns in the underlying assumptions that different people make and how those assumptions shape their worldview, what they view as true, and what they hope to accomplish. ... (ies), develop a theoretical framework (in quantitative research), select an appropriate methodology, and make sure the research question(s ...

A goal of quantitative research is to maintain objectivity, in other words, to reduce the influence of the researcher on data collection as much as possible. Some qualitative researchers also attempt to reduce their own influence on the research. ... Seek to challenge, elaborate, and refine your assumptions throughout the research. As you ...

edge, reality, and the researcher's role. These assumptions shape the research endeavor, from the methodology employed to the type of questions asked. When institutional researchers make the choice between quantitative or quali- tative research methods, they tacitly assume a structure of knowledge, an under-

Hypothesis testing is a fundamental aspect of quantitative research, employed to make inferences or draw conclusions about populations based on sample data. This test involves formulating a null hypothesis (H 0) and an alternative hypothesis (H a, where a = 1, 2, . . .

Importance of a Theoretical Framework. Guides Research Design: Helps identify research questions, hypotheses, and methodologies. Establishes Relevance: Connects the study to established theories and highlights its contribution to the field. Explains Relationships: Provides clarity on how variables interact within the research context. Improves Rigor: Ensures the study is grounded in academic ...

Our aim is to make our implicit assumptions more explicit so that we can: • Make our thinking visible to each other • Invite alternative perspectives about how systems work or how change will occur • Test the validity of our assumptions with evidence. Guidance on Developing Assumptions Assumptions are rarely all right or all wrong.

For institutional researchers, the choice to use a quantitative or qualitative approach to research is dictated by time, money, resources, and staff. Frequently, the choice to use one or the other approach is made at the method level. Choices made at this level generally have rigor, but ignore the underlying philosophical assumptions structuring beliefs about methodology, knowledge, and ...

In quantitative research designs, statistical models come with accompanying assumptions, which can vary in their stringency. These assumptions typically pertain to data characteristics, including distributions, correlations, and variable types. ... When we make incorrect or unreasonable assumption during research, we will get false conclusions ...