Stanford Prison Experiment: Zimbardo’s Famous Study

Saul McLeod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul McLeod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

- The experiment was conducted in 1971 by psychologist Philip Zimbardo to examine situational forces versus dispositions in human behavior.

- 24 young, healthy, psychologically normal men were randomly assigned to be “prisoners” or “guards” in a simulated prison environment.

- The experiment had to be terminated after only 6 days due to the extreme, pathological behavior emerging in both groups. The situational forces overwhelmed the dispositions of the participants.

- Pacifist young men assigned as guards began behaving sadistically, inflicting humiliation and suffering on the prisoners. Prisoners became blindly obedient and allowed themselves to be dehumanized.

- The principal investigator, Zimbardo, was also transformed into a rigid authority figure as the Prison Superintendent.

- The experiment demonstrated the power of situations to alter human behavior dramatically. Even good, normal people can do evil things when situational forces push them in that direction.

Zimbardo and his colleagues (1973) were interested in finding out whether the brutality reported among guards in American prisons was due to the sadistic personalities of the guards (i.e., dispositional) or had more to do with the prison environment (i.e., situational).

For example, prisoners and guards may have personalities that make conflict inevitable, with prisoners lacking respect for law and order and guards being domineering and aggressive.

Alternatively, prisoners and guards may behave in a hostile manner due to the rigid power structure of the social environment in prisons.

Zimbardo predicted the situation made people act the way they do rather than their disposition (personality).

To study people’s roles in prison situations, Zimbardo converted a basement of the Stanford University psychology building into a mock prison.

He advertised asking for volunteers to participate in a study of the psychological effects of prison life.

The 75 applicants who answered the ad were given diagnostic interviews and personality tests to eliminate candidates with psychological problems, medical disabilities, or a history of crime or drug abuse.

24 men judged to be the most physically & mentally stable, the most mature, & the least involved in antisocial behaviors were chosen to participate.

The participants did not know each other prior to the study and were paid $15 per day to take part in the experiment.

Participants were randomly assigned to either the role of prisoner or guard in a simulated prison environment. There were two reserves, and one dropped out, finally leaving ten prisoners and 11 guards.

Prisoners were treated like every other criminal, being arrested at their own homes, without warning, and taken to the local police station. They were fingerprinted, photographed and ‘booked.’

Then they were blindfolded and driven to the psychology department of Stanford University, where Zimbardo had had the basement set out as a prison, with barred doors and windows, bare walls and small cells. Here the deindividuation process began.

When the prisoners arrived at the prison they were stripped naked, deloused, had all their personal possessions removed and locked away, and were given prison clothes and bedding. They were issued a uniform, and referred to by their number only.

The use of ID numbers was a way to make prisoners feel anonymous. Each prisoner had to be called only by his ID number and could only refer to himself and the other prisoners by number.

Their clothes comprised a smock with their number written on it, but no underclothes. They also had a tight nylon cap to cover their hair, and a locked chain around one ankle.

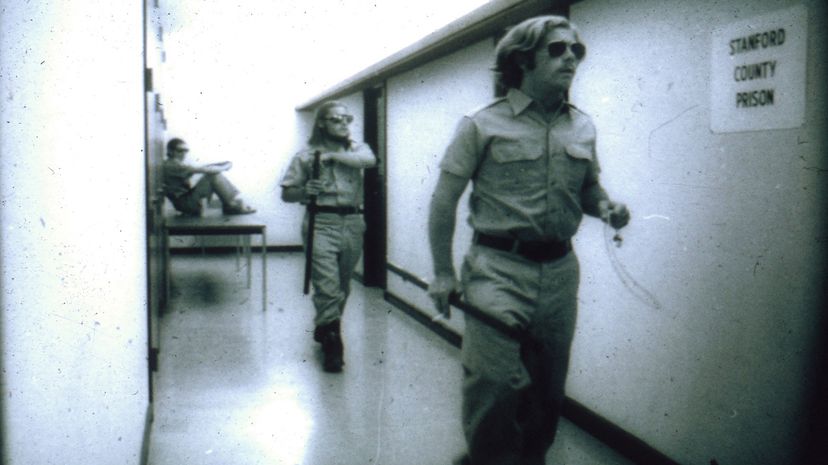

All guards were dressed in identical uniforms of khaki, and they carried a whistle around their neck and a billy club borrowed from the police. Guards also wore special sunglasses, to make eye contact with prisoners impossible.

Three guards worked shifts of eight hours each (the other guards remained on call). Guards were instructed to do whatever they thought was necessary to maintain law and order in the prison and to command the respect of the prisoners. No physical violence was permitted.

Zimbardo observed the behavior of the prisoners and guards (as a researcher), and also acted as a prison warden.

Within a very short time both guards and prisoners were settling into their new roles, with the guards adopting theirs quickly and easily.

Asserting Authority

Within hours of beginning the experiment, some guards began to harass prisoners. At 2:30 A.M. prisoners were awakened from sleep by blasting whistles for the first of many “counts.”

The counts served as a way to familiarize the prisoners with their numbers. More importantly, they provided a regular occasion for the guards to exercise control over the prisoners.

The prisoners soon adopted prisoner-like behavior too. They talked about prison issues a great deal of the time. They ‘told tales’ on each other to the guards.

They started taking the prison rules very seriously, as though they were there for the prisoners’ benefit and infringement would spell disaster for all of them. Some even began siding with the guards against prisoners who did not obey the rules.

Physical Punishment

The prisoners were taunted with insults and petty orders, they were given pointless and boring tasks to accomplish, and they were generally dehumanized.

Push-ups were a common form of physical punishment imposed by the guards. One of the guards stepped on the prisoners” backs while they did push-ups, or made other prisoners sit on the backs of fellow prisoners doing their push-ups.

Asserting Independence

Because the first day passed without incident, the guards were surprised and totally unprepared for the rebellion which broke out on the morning of the second day.

During the second day of the experiment, the prisoners removed their stocking caps, ripped off their numbers, and barricaded themselves inside the cells by putting their beds against the door.

The guards called in reinforcements. The three guards who were waiting on stand-by duty came in and the night shift guards voluntarily remained on duty.

Putting Down the Rebellion

The guards retaliated by using a fire extinguisher which shot a stream of skin-chilling carbon dioxide, and they forced the prisoners away from the doors. Next, the guards broke into each cell, stripped the prisoners naked and took the beds out.

The ringleaders of the prisoner rebellion were placed into solitary confinement. After this, the guards generally began to harass and intimidate the prisoners.

Special Privileges

One of the three cells was designated as a “privilege cell.” The three prisoners least involved in the rebellion were given special privileges. The guards gave them back their uniforms and beds and allowed them to wash their hair and brush their teeth.

Privileged prisoners also got to eat special food in the presence of the other prisoners who had temporarily lost the privilege of eating. The effect was to break the solidarity among prisoners.

Consequences of the Rebellion

Over the next few days, the relationships between the guards and the prisoners changed, with a change in one leading to a change in the other. Remember that the guards were firmly in control and the prisoners were totally dependent on them.

As the prisoners became more dependent, the guards became more derisive towards them. They held the prisoners in contempt and let the prisoners know it. As the guards’ contempt for them grew, the prisoners became more submissive.

As the prisoners became more submissive, the guards became more aggressive and assertive. They demanded ever greater obedience from the prisoners. The prisoners were dependent on the guards for everything, so tried to find ways to please the guards, such as telling tales on fellow prisoners.

Prisoner #8612

Less than 36 hours into the experiment, Prisoner #8612 began suffering from acute emotional disturbance, disorganized thinking, uncontrollable crying, and rage.

After a meeting with the guards where they told him he was weak, but offered him “informant” status, #8612 returned to the other prisoners and said “You can”t leave. You can’t quit.”

Soon #8612 “began to act ‘crazy,’ to scream, to curse, to go into a rage that seemed out of control.” It wasn’t until this point that the psychologists realized they had to let him out.

A Visit from Parents

The next day, the guards held a visiting hour for parents and friends. They were worried that when the parents saw the state of the jail, they might insist on taking their sons home. Guards washed the prisoners, had them clean and polish their cells, fed them a big dinner and played music on the intercom.

After the visit, rumors spread of a mass escape plan. Afraid that they would lose the prisoners, the guards and experimenters tried to enlist help and facilities of the Palo Alto police department.

The guards again escalated the level of harassment, forcing them to do menial, repetitive work such as cleaning toilets with their bare hands.

Catholic Priest

Zimbardo invited a Catholic priest who had been a prison chaplain to evaluate how realistic our prison situation was. Half of the prisoners introduced themselves by their number rather than name.

The chaplain interviewed each prisoner individually. The priest told them the only way they would get out was with the help of a lawyer.

Prisoner #819

Eventually, while talking to the priest, #819 broke down and began to cry hysterically, just like two previously released prisoners had.

The psychologists removed the chain from his foot, the cap off his head, and told him to go and rest in a room that was adjacent to the prison yard. They told him they would get him some food and then take him to see a doctor.

While this was going on, one of the guards lined up the other prisoners and had them chant aloud:

“Prisoner #819 is a bad prisoner. Because of what Prisoner #819 did, my cell is a mess, Mr. Correctional Officer.”

The psychologists realized #819 could hear the chanting and went back into the room where they found him sobbing uncontrollably. The psychologists tried to get him to agree to leave the experiment, but he said he could not leave because the others had labeled him a bad prisoner.

Back to Reality

At that point, Zimbardo said, “Listen, you are not #819. You are [his name], and my name is Dr. Zimbardo. I am a psychologist, not a prison superintendent, and this is not a real prison. This is just an experiment, and those are students, not prisoners, just like you. Let’s go.”

He stopped crying suddenly, looked up and replied, “Okay, let’s go,“ as if nothing had been wrong.

An End to the Experiment

Zimbardo (1973) had intended that the experiment should run for two weeks, but on the sixth day, it was terminated, due to the emotional breakdowns of prisoners, and excessive aggression of the guards.

Christina Maslach, a recent Stanford Ph.D. brought in to conduct interviews with the guards and prisoners, strongly objected when she saw the prisoners being abused by the guards.

Filled with outrage, she said, “It’s terrible what you are doing to these boys!” Out of 50 or more outsiders who had seen our prison, she was the only one who ever questioned its morality.

Zimbardo (2008) later noted, “It wasn’t until much later that I realized how far into my prison role I was at that point — that I was thinking like a prison superintendent rather than a research psychologist.“

This led him to prioritize maintaining the experiment’s structure over the well-being and ethics involved, thereby highlighting the blurring of roles and the profound impact of the situation on human behavior.

Here’s a quote that illustrates how Philip Zimbardo, initially the principal investigator, became deeply immersed in his role as the “Stanford Prison Superintendent (April 19, 2011):

“By the third day, when the second prisoner broke down, I had already slipped into or been transformed into the role of “Stanford Prison Superintendent.” And in that role, I was no longer the principal investigator, worried about ethics. When a prisoner broke down, what was my job? It was to replace him with somebody on our standby list. And that’s what I did. There was a weakness in the study in not separating those two roles. I should only have been the principal investigator, in charge of two graduate students and one undergraduate.”

According to Zimbardo and his colleagues, the Stanford Prison Experiment revealed how people will readily conform to the social roles they are expected to play, especially if the roles are as strongly stereotyped as those of the prison guards.

Because the guards were placed in a position of authority, they began to act in ways they would not usually behave in their normal lives.

The “prison” environment was an important factor in creating the guards’ brutal behavior (none of the participants who acted as guards showed sadistic tendencies before the study).

Therefore, the findings support the situational explanation of behavior rather than the dispositional one.

Zimbardo proposed that two processes can explain the prisoner’s “final submission.”

Deindividuation may explain the behavior of the participants; especially the guards. This is a state when you become so immersed in the norms of the group that you lose your sense of identity and personal responsibility.

The guards may have been so sadistic because they did not feel what happened was down to them personally – it was a group norm. They also may have lost their sense of personal identity because of the uniform they wore.

Also, learned helplessness could explain the prisoner’s submission to the guards. The prisoners learned that whatever they did had little effect on what happened to them. In the mock prison the unpredictable decisions of the guards led the prisoners to give up responding.

After the prison experiment was terminated, Zimbardo interviewed the participants. Here’s an excerpt:

‘Most of the participants said they had felt involved and committed. The research had felt “real” to them. One guard said, “I was surprised at myself. I made them call each other names and clean the toilets out with their bare hands. I practically considered the prisoners cattle and I kept thinking I had to watch out for them in case they tried something.” Another guard said “Acting authoritatively can be fun. Power can be a great pleasure.” And another: “… during the inspection I went to Cell Two to mess up a bed which a prisoner had just made and he grabbed me, screaming that he had just made it and that he was not going to let me mess it up. He grabbed me by the throat and although he was laughing I was pretty scared. I lashed out with my stick and hit him on the chin although not very hard, and when I freed myself I became angry.”’

Most of the guards found it difficult to believe that they had behaved in the brutal ways that they had. Many said they hadn’t known this side of them existed or that they were capable of such things.

The prisoners, too, couldn’t believe that they had responded in the submissive, cowering, dependent way they had. Several claimed to be assertive types normally.

When asked about the guards, they described the usual three stereotypes that can be found in any prison: some guards were good, some were tough but fair, and some were cruel.

A further explanation for the behavior of the participants can be described in terms of reinforcement. The escalation of aggression and abuse by the guards could be seen as being due to the positive reinforcement they received both from fellow guards and intrinsically in terms of how good it made them feel to have so much power.

Similarly, the prisoners could have learned through negative reinforcement that if they kept their heads down and did as they were told, they could avoid further unpleasant experiences.

Critical Evaluation

Ecological validity.

The Stanford Prison Experiment is criticized for lacking ecological validity in its attempt to simulate a real prison environment. Specifically, the “prison” was merely a setup in the basement of Stanford University’s psychology department.

The student “guards” lacked professional training, and the experiment’s duration was much shorter than real prison sentences. Furthermore, the participants, who were college students, didn’t reflect the diverse backgrounds typically found in actual prisons in terms of ethnicity, education, and socioeconomic status.

None had prior prison experience, and they were chosen due to their mental stability and low antisocial tendencies. Additionally, the mock prison lacked spaces for exercise or rehabilitative activities.

Demand characteristics

Demand characteristics could explain the findings of the study. Most of the guards later claimed they were simply acting. Because the guards and prisoners were playing a role, their behavior may not be influenced by the same factors which affect behavior in real life. This means the study’s findings cannot be reasonably generalized to real life, such as prison settings. I.e, the study has low ecological validity.

One of the biggest criticisms is that strong demand characteristics confounded the study. Banuazizi and Movahedi (1975) found that the majority of respondents, when given a description of the study, were able to guess the hypothesis and predict how participants were expected to behave.

This suggests participants may have simply been playing out expected roles rather than genuinely conforming to their assigned identities.

In addition, revelations by Zimbardo (2007) indicate he actively encouraged the guards to be cruel and oppressive in his orientation instructions prior to the start of the study. For example, telling them “they [the prisoners] will be able to do nothing and say nothing that we don’t permit.”

He also tacitly approved of abusive behaviors as the study progressed. This deliberate cueing of how participants should act, rather than allowing behavior to unfold naturally, indicates the study findings were likely a result of strong demand characteristics rather than insightful revelations about human behavior.

However, there is considerable evidence that the participants did react to the situation as though it was real. For example, 90% of the prisoners’ private conversations, which were monitored by the researchers, were on the prison conditions, and only 10% of the time were their conversations about life outside of the prison.

The guards, too, rarely exchanged personal information during their relaxation breaks – they either talked about ‘problem prisoners,’ other prison topics, or did not talk at all. The guards were always on time and even worked overtime for no extra pay.

When the prisoners were introduced to a priest, they referred to themselves by their prison number, rather than their first name. Some even asked him to get a lawyer to help get them out.

Fourteen years after his experience as prisoner 8612 in the Stanford Prison Experiment, Douglas Korpi, now a prison psychologist, reflected on his time and stated (Musen and Zimbardo 1992):

“The Stanford Prison Experiment was a very benign prison situation and it promotes everything a normal prison promotes — the guard role promotes sadism, the prisoner role promotes confusion and shame”.

Sample bias

The study may also lack population validity as the sample comprised US male students. The study’s findings cannot be applied to female prisons or those from other countries. For example, America is an individualist culture (where people are generally less conforming), and the results may be different in collectivist cultures (such as Asian countries).

Carnahan and McFarland (2007) have questioned whether self-selection may have influenced the results – i.e., did certain personality traits or dispositions lead some individuals to volunteer for a study of “prison life” in the first place?

All participants completed personality measures assessing: aggression, authoritarianism, Machiavellianism, narcissism, social dominance, empathy, and altruism. Participants also answered questions on mental health and criminal history to screen out any issues as per the original SPE.

Results showed that volunteers for the prison study, compared to the control group, scored significantly higher on aggressiveness, authoritarianism, Machiavellianism, narcissism, and social dominance. They scored significantly lower on empathy and altruism.

A follow-up role-playing study found that self-presentation biases could not explain these differences. Overall, the findings suggest that volunteering for the prison study was influenced by personality traits associated with abusive tendencies.

Zimbardo’s conclusion may be wrong

While implications for the original SPE are speculative, this lends support to a person-situation interactionist perspective, rather than a purely situational account.

It implies that certain individuals are drawn to and selected into situations that fit their personality, and that group composition can shape behavior through mutual reinforcement.

Contributions to psychology

Another strength of the study is that the harmful treatment of participants led to the formal recognition of ethical guidelines by the American Psychological Association. Studies must now undergo an extensive review by an institutional review board (US) or ethics committee (UK) before they are implemented.

Most institutions, such as universities, hospitals, and government agencies, require a review of research plans by a panel. These boards review whether the potential benefits of the research are justifiable in light of the possible risk of physical or psychological harm.

These boards may request researchers make changes to the study’s design or procedure, or, in extreme cases, deny approval of the study altogether.

Contribution to prison policy

A strength of the study is that it has altered the way US prisons are run. For example, juveniles accused of federal crimes are no longer housed before trial with adult prisoners (due to the risk of violence against them).

However, in the 25 years since the SPE, U.S. prison policy has transformed in ways counter to SPE insights (Haney & Zimbardo, 1995):

- Rehabilitation was abandoned in favor of punishment and containment. Prison is now seen as inflicting pain rather than enabling productive re-entry.

- Sentencing became rigid rather than accounting for inmates’ individual contexts. Mandatory minimums and “three strikes” laws over-incarcerate nonviolent crimes.

- Prison construction boomed, and populations soared, disproportionately affecting minorities. From 1925 to 1975, incarceration rates held steady at around 100 per 100,000. By 1995, rates tripled to over 600 per 100,000.

- Drug offenses account for an increasing proportion of prisoners. Nonviolent drug offenses make up a large share of the increased incarceration.

- Psychological perspectives have been ignored in policymaking. Legislators overlooked insights from social psychology on the power of contexts in shaping behavior.

- Oversight retreated, with courts deferring to prison officials and ending meaningful scrutiny of conditions. Standards like “evolving decency” gave way to “legitimate” pain.

- Supermax prisons proliferated, isolating prisoners in psychological trauma-inducing conditions.

The authors argue psychologists should reengage to:

- Limit the use of imprisonment and adopt humane alternatives based on the harmful effects of prison environments

- Assess prisons’ total environments, not just individual conditions, given situational forces interact

- Prepare inmates for release by transforming criminogenic post-release contexts

- Address socioeconomic risk factors, not just incarcerate individuals

- Develop contextual prediction models vs. focusing only on static traits

- Scrutinize prison systems independently, not just defer to officials shaped by those environments

- Generate creative, evidence-based reforms to counter over-punitive policies

Psychology once contributed to a more humane system and can again counter the U.S. “rage to punish” with contextual insights (Haney & Zimbardo, 1998).

Evidence for situational factors

Zimbardo (1995) further demonstrates the power of situations to elicit evil actions from ordinary, educated people who likely would never have done such things otherwise. It was another situation-induced “transformation of human character.”

- Unit 731 was a covert biological and chemical warfare research unit of the Japanese army during WWII.

- It was led by General Shiro Ishii and involved thousands of doctors and researchers.

- Unit 731 set up facilities near Harbin, China to conduct lethal human experimentation on prisoners, including Allied POWs.

- Experiments involved exposing prisoners to things like plague, anthrax, mustard gas, and bullets to test biological weapons. They infected prisoners with diseases and monitored their deaths.

- At least 3,000 prisoners died from these brutal experiments. Many were killed and dissected.

- The doctors in Unit 731 obeyed orders unquestioningly and conducted these experiments in the name of “medical science.”

- After the war, the vast majority of doctors who participated faced no punishment and went on to have prestigious careers. This was largely covered up by the U.S. in exchange for data.

- It shows how normal, intelligent professionals can be led by situational forces to systematically dehumanize victims and conduct incredibly cruel and lethal experiments on people.

- Even healers trained to preserve life used their expertise to destroy lives when the situational forces compelled obedience, nationalism, and wartime enmity.

Evidence for an interactionist approach

The results are also relevant for explaining abuses by American guards at Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq.

An interactionist perspective recognizes that volunteering for roles as prison guards attracts those already prone to abusive tendencies, which are intensified by the prison context.

This counters a solely situationist view of good people succumbing to evil situational forces.

Ethical Issues

The study has received many ethical criticisms, including lack of fully informed consent by participants as Zimbardo himself did not know what would happen in the experiment (it was unpredictable). Also, the prisoners did not consent to being “arrested” at home. The prisoners were not told partly because final approval from the police wasn’t given until minutes before the participants decided to participate, and partly because the researchers wanted the arrests to come as a surprise. However, this was a breach of the ethics of Zimbardo’s own contract that all of the participants had signed.

Protection of Participants

Participants playing the role of prisoners were not protected from psychological harm, experiencing incidents of humiliation and distress. For example, one prisoner had to be released after 36 hours because of uncontrollable bursts of screaming, crying, and anger.

Here’s a quote from Philip G. Zimbardo, taken from an interview on the Stanford Prison Experiment’s 40th anniversary (April 19, 2011):

“In the Stanford prison study, people were stressed, day and night, for 5 days, 24 hours a day. There’s no question that it was a high level of stress because five of the boys had emotional breakdowns, the first within 36 hours. Other boys that didn’t have emotional breakdowns were blindly obedient to corrupt authority by the guards and did terrible things to each other. And so it is no question that that was unethical. You can’t do research where you allow people to suffer at that level.”

“After the first one broke down, we didn’t believe it. We thought he was faking. There was actually a rumor he was faking to get out. He was going to bring his friends in to liberate the prison. And/or we believed our screening procedure was inadequate, [we believed] that he had some mental defect that we did not pick up. At that point, by the third day, when the second prisoner broke down, I had already slipped into or been transformed into the role of “Stanford Prison Superintendent.” And in that role, I was no longer the principal investigator, worried about ethics.”

However, in Zimbardo’s defense, the emotional distress experienced by the prisoners could not have been predicted from the outset.

Approval for the study was given by the Office of Naval Research, the Psychology Department, and the University Committee of Human Experimentation.

This Committee also did not anticipate the prisoners’ extreme reactions that were to follow. Alternative methodologies were looked at that would cause less distress to the participants but at the same time give the desired information, but nothing suitable could be found.

Withdrawal

Although guards were explicitly instructed not to physically harm prisoners at the beginning of the Stanford Prison Experiment, they were allowed to induce feelings of boredom, frustration, arbitrariness, and powerlessness among the inmates.

This created a pervasive atmosphere where prisoners genuinely believed and even reinforced among each other, that they couldn’t leave the experiment until their “sentence” was completed, mirroring the inescapability of a real prison.

Even though two participants (8612 and 819) were released early, the impact of the environment was so profound that prisoner 416, reflecting on the experience two months later, described it as a “prison run by psychologists rather than by the state.”

Extensive group and individual debriefing sessions were held, and all participants returned post-experimental questionnaires several weeks, then several months later, and then at yearly intervals. Zimbardo concluded there were no lasting negative effects.

Zimbardo also strongly argues that the benefits gained from our understanding of human behavior and how we can improve society should outbalance the distress caused by the study.

However, it has been suggested that the US Navy was not so much interested in making prisons more human and were, in fact, more interested in using the study to train people in the armed services to cope with the stresses of captivity.

Discussion Questions

What are the effects of living in an environment with no clocks, no view of the outside world, and minimal sensory stimulation?

Consider the psychological consequences of stripping, delousing, and shaving the heads of prisoners or members of the military. Whattransformations take place when people go through an experience like this?

The prisoners could have left at any time, and yet, they didn’t. Why?

After the study, how do you think the prisoners and guards felt?

If you were the experimenter in charge, would you have done this study? Would you have terminated it earlier? Would you have conducted a follow-up study?

Frequently Asked Questions

What happened to prisoner 8612 after the experiment.

Douglas Korpi, as prisoner 8612, was the first to show signs of severe distress and demanded to be released from the experiment. He was released on the second day, and his reaction to the simulated prison environment highlighted the study’s ethical issues and the potential harm inflicted on participants.

After the experiment, Douglas Korpi graduated from Stanford University and earned a Ph.D. in clinical psychology. He pursued a career as a psychotherapist, helping others with their mental health struggles.

Why did Zimbardo not stop the experiment?

Zimbardo did not initially stop the experiment because he became too immersed in his dual role as the principal investigator and the prison superintendent, causing him to overlook the escalating abuse and distress among participants.

It was only after an external observer, Christina Maslach, raised concerns about the participants’ well-being that Zimbardo terminated the study.

What happened to the guards in the Stanford Prison Experiment?

In the Stanford Prison Experiment, the guards exhibited abusive and authoritarian behavior, using psychological manipulation, humiliation, and control tactics to assert dominance over the prisoners. This ultimately led to the study’s early termination due to ethical concerns.

What did Zimbardo want to find out?

Zimbardo aimed to investigate the impact of situational factors and power dynamics on human behavior, specifically how individuals would conform to the roles of prisoners and guards in a simulated prison environment.

He wanted to explore whether the behavior displayed in prisons was due to the inherent personalities of prisoners and guards or the result of the social structure and environment of the prison itself.

What were the results of the Stanford Prison Experiment?

The results of the Stanford Prison Experiment showed that situational factors and power dynamics played a significant role in shaping participants’ behavior. The guards became abusive and authoritarian, while the prisoners became submissive and emotionally distressed.

The experiment revealed how quickly ordinary individuals could adopt and internalize harmful behaviors due to their assigned roles and the environment.

Banuazizi, A., & Movahedi, S. (1975). Interpersonal dynamics in a simulated prison: A methodological analysis. American Psychologist, 30 , 152-160.

Carnahan, T., & McFarland, S. (2007). Revisiting the Stanford prison experiment: Could participant self-selection have led to the cruelty? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 33, 603-614.

Drury, S., Hutchens, S. A., Shuttlesworth, D. E., & White, C. L. (2012). Philip G. Zimbardo on his career and the Stanford Prison Experiment’s 40th anniversary. History of Psychology , 15 (2), 161.

Griggs, R. A., & Whitehead, G. I., III. (2014). Coverage of the Stanford Prison Experiment in introductory social psychology textbooks. Teaching of Psychology, 41 , 318 –324.

Haney, C., Banks, W. C., & Zimbardo, P. G. (1973). A study of prisoners and guards in a simulated prison . Naval Research Review , 30, 4-17.

Haney, C., & Zimbardo, P. (1998). The past and future of U.S. prison policy: Twenty-five years after the Stanford Prison Experiment. American Psychologist, 53 (7), 709–727.

Musen, K. & Zimbardo, P. (1992) (DVD) Quiet Rage: The Stanford Prison Experiment Documentary.

Zimbardo, P. G. (Consultant, On-Screen Performer), Goldstein, L. (Producer), & Utley, G. (Correspondent). (1971, November 26). Prisoner 819 did a bad thing: The Stanford Prison Experiment [Television series episode]. In L. Goldstein (Producer), Chronolog. New York, NY: NBC-TV.

Zimbardo, P. G. (1973). On the ethics of intervention in human psychological research: With special reference to the Stanford prison experiment. Cognition , 2 (2), 243-256.

Zimbardo, P. G. (1995). The psychology of evil: A situationist perspective on recruiting good people to engage in anti-social acts. Japanese Journal of Social Psychology , 11 (2), 125-133.

Zimbardo, P.G. (2007). The Lucifer effect: Understanding how good people turn evil . New York, NY: Random House.

Further Information

- Reicher, S., & Haslam, S. A. (2006). Rethinking the psychology of tyranny: The BBC prison study. The British Journal of Social Psychology, 45 , 1.

- Coverage of the Stanford Prison Experiment in introductory psychology textbooks

- The Stanford Prison Experiment Official Website

- Login / Sign Up

Fearless journalism needs your support now more than ever

Our mission could not be more clear and more necessary: We have a duty to explain what just happened, and why, and what it means for you. We need clear-eyed journalism that helps you understand what really matters. Reporting that brings clarity in increasingly chaotic times. Reporting that is driven by truth, not by what people in power want you to believe.

We rely on readers like you to fund our journalism. Will you support our work and become a Vox Member today?

Philip Zimbardo defends the Stanford Prison Experiment, his most famous work

What’s the scientific value of the Stanford Prison Experiment? Zimbardo responds to the new allegations against his work.

by Brian Resnick

For decades, the story of the famous Stanford Prison Experiment has gone like this: Stanford professor Philip Zimbardo assigned paid volunteers to be either inmates or guards in a simulated prison in the basement of the school‘s psychology building. Very quickly, the guards became cruel, and the prisoners more submissive and depressed. The situation grew chaotic, and the experiment, meant to last two weeks, had to be ended after five days.

The lesson drawn from the research was that situations can bring out the worst in people. That, in the absence of firm instructions of how to act, we’ll act in accordance to the roles we’re assigned. The tale, which was made into a feature film , has been a lens through which we can understand human-rights violations, like American soldier’s maltreatment of inmates at the Abu Ghraib in Iraq in the early 2000s.

This month, the scientific validity of the experiment was boldly challenged. In a thoroughly reported exposé on Medium, journalist Ben Blum found compelling evidence that the experiment wasn’t as naturalistic and un-manipulated by the experimenters as we’ve been told.

A recording from the experiment reveals that the “warden,” a research assistant, told a reluctant guard that “the guards have to know that every guard is going to be what we call a ‘tough guard.’” The warden implored the guard to act tough because “we hope will come out of the study is a very serious recommendation for [criminal justice] reform.” The implication being that if the guard didn’t play the part, the study would fail.

Additionally, one of the “prisoners” in the study told Blum that he was “acting” during a what was observed to be a mental breakdown.

These new findings don’t mean that everything that happened in the experiment was theater. The “prisoners” really did rebel at one point, and the “guards” were cruel. But the new evidence suggests that the main conclusion of the experiment — the one that has been republished in psychology textbooks for years — doesn’t necessarily hold up. Zimbardo stated over and over the behavior seen in the experiment was the result of their own minds conforming to a situation. The new evidence suggests there was a lot more going on.

I wrote a piece highlighting Blum’s exposé and putting the prison experiment in the larger context of psychology’s replication crisis. Our headline stated “we just learned it [the Stanford Prison Experiment] was a fraud.”

Fraud is a moral judgment. And Zimbardo, now a professor emeritus, wrote to Vox, unhappy with this characterization of his study. (You can Zimbardo’s full written response to the criticisms here .)

So I called Zimbardo up to ask about the evidence in Blum’s piece. I also wanted to know: As a scientist, what do you do when the narrative of your most famous work changes dramatically and spirals out of your own control?

The conversation was tense. At one point, Zimbardo threatened to hang up.

Zimbardo believes Blum (and Vox) got the story wrong. He says only one guard was prodded to act tougher. (We did not discuss Blum’s evidence that the “prisoners” in the experiment were held against their will, despite pleas to leave.)

After talking with him, the results of the prison experiment still seem unscientific and untrustworthy. It’s an interesting demonstration, but should enduring lessons in psychology be based off of it? I doubt it.

Here’s our conversation, which has been edited for length and clarity.

Brian Resnick

Here’s my understanding of the criticisms that have come to light recently about the Stanford Prison Experiment.

For years, the conclusion that has been drawn from the study was that circumstances can bring out the worst in people or encourage bad behavior. And when some people are given power, and some people are stripped of it, that fosters ugly behavior.

What’s comes to light — what I got out of that Ben Blum’s report — was that it might not have all been the circumstance. That these guards that you employed were possibly coached in some ways.

There’s audio. And for me, it sounded pretty compelling that the warden in your experiment, who I understand was an experimental collaborator — was calling out a guard for not being tough enough. [The warden told the guard, “The guards have to know that every guard is going to be what we call a ‘tough guard.’” Listen to the tape here .]

So does that not invalidate the conclusion?

Philip Zimbardo

Not at all!

And why not?

Because he’s talking to one guard who was doing nothing. These are people we’ve hired who are doing it for a salary, $15 a day, to play the role of guard. And Jaffe [the warden] picks on this guy because he is doing nothing. He’s sitting on the sideline, doing nothing, watching. He’s gotta earn his keep as a guard.

The point is telling a guard to be tough does not mean telling a guard to be mean, to be cruel, to be sadistic, which many of the guards became of their own volition playing the role of what they thought was a prison guard. So I reject your assumption entirely.

Here’s the description of the experiment as written on your website: It says “the guards made up their own set of rules which they carried into effect.” In another paper , you wrote that the guards’ behavior was left up “to each subject’s prior societal learning of the meaning of prisons.”

But here’s a different possibility: Do you think it is possible that some of these guards were acting to please you, to please the study, and to do something good for science?

Even without telling the guards to explicitly do something, they might have gotten the impression that it was important for them to play these roles. And they were compelled to because of your authority.

Some of them might, but I think most of them didn’t.

For many of them, it was simply a way to make $15 a day during a two-week summer break between summer school and the start of classes in September. It was nothing more than that. It was not wanting to help science.

Some of them were increasingly mean, cruel, and sadistic way beyond any definition of tough. Some of them were guards who simply enforced the rules. And some of them were “good guards” who never did anything abusive to the prisoners. So it’s not that the situation brought a single quality in the guard. It’s a mix.

The criticism that you’re raising, that Blum raised, that others are raising, is that we told the guards to do what they ended up doing. And therefore, [the results were due to] obedience to authority, and it’s not the evolution of cruel behavior in the situation of a prison-like environment.

And I reject that.

Is it possible that some of the “prisoners” in your experiment were acting, playing along?

Zero? How can you say zero?

Okay, I can’t say.

I mean, the point was they locked themselves in their cells, they ripped off their numbers, they’re yelling and cursing at the guards. So, yeah, they could be acting. But why would they be acting. ... What would they get out of that?

Blum quoted one of the prisoners, Douglas Korpi, who had a breakdown. Korpi told Blum that he was acting. That he was in the midsts of studying for the GREs and just really wanted to get out of the experiment. Korpi told Blum, “Anybody who is a clinician would know that I was faking.”

Brian, Brian, I’m telling you every fucking thing that Ben Blum said is a lie; it’s false.

Nothing Korpi said to Ben Blum has any truth, zero. Look at Quiet Rage [a documentary about the prison experiment], look at where he says, “I was overcome in that situation. I broke down, I lost control of myself.”

Retrospectively now, he’s ashamed of having broken down. So he says he “was studying the Graduate Record Exam, I was faking it, I wanted to show I could get out and liberate my colleagues,” etc, etc.

So he is the least reliable source of any information about the study, except he documents the power of the situation to get somebody who’s psychologically normal, 36 hours before, who in an experiment, knowing it’s an experiment, has an emotional “breakdown,” and had to be released.

Let’s say: Regardless of whether guards were coached or not...

Brian, I’m gonna stop you.

Can I finish the question?

A guard, a single guard, okay? When you say guards you’re slipping back into your assumption, you’re slipping back to be like Blum. A guard was coached to be tough, and end of sentence there.

[Note: As a reminder, the tape of the experiment quoted the Jaffe, the “warden,” who played a critical role in leading the experiment, as saying, “The guards have to know that every guard is going to be what we call a ‘tough guard.’” Also, as Blum discovered in the Stanford archives, Jaffe wrote in his notes , “I was given the responsibility of trying to elicit ‘tough-guard’ behavior.” Which, again, raises suspicions that the experiment wasn’t as naturalistic as the experimenters implied.]

What I want to ask is: What is the case that this experiment should be seen as anything more than an anecdote? I don’t think anyone denies its historical value. It’s an interesting demonstration. Ideas that generated from it are worthwhile to follow up on and to study more carefully. Do you think the experiment itself has a definitive scientific value? If so, what is it?

It depends what you mean by scientific value. From the beginning, I have always said it’s a demonstration. The only thing that makes it an experiment is the random assignment to prisoners and guards, that’s the independent variable. There is no control group. There’s no comparison group. So it doesn’t fit the standards of what it means to be “an experiment.” It’s a very powerful demonstration of a psychological phenomenon, and it has had relevance.

So, yes, if you want to call it anecdote, that’s one way to demean it. If you want to say, “Is it a scientifically valid conclusion?” I say ... it doesn’t have to be scientifically valid. It means it’s a conclusion drawn from this powerful, unique demonstration.

Would you agree, as a scientist, that an early demonstration of an idea is bound to be reinterpreted in time, bound to be reevaluated?

Oh, they should. The essence of science is you don’t believe anything until it has a) been replicated, or b) been critically evaluated, as the study is being done now. I’m hoping a positive consequence of all of this is a better, fuller appreciation of what happened in the Stanford prison study.

Let me just add one thing: There are many, many classic studies that are now all under attack. ... by psychologists from a very different domain. It’s curious.

I’ve talked to a lot of researchers who are interested in replication, and reevaluating past work. They want to correct the record. I think they’re scared about what happens to the credibility of science if they don’t scrutinize the classics.

And I wonder from your point of view, as a scientist, do you need to be okay with losing control of the narrative of your work as it gets reevaluated?

Of course. The moment, the moment any of it was published, the moment any of this was put online, which I did as soon as I could, I lost. ... You lose control of it. Once it’s out there it’s not in your head anymore. Once it’s out in any public forum, then, of course, I lost control of “the narrative.”

Is it a study with flaws? I was the first to admit that many, many years ago.

A study like the prison experiment might just be too big and complicated, with too many inputs, too many variables, to really nail down or understand a single, simple conclusion from it.

The single conclusion is a broad line: Human behavior, for many people, is much more under the influence of social situational variables than we had ever thought of before.

I will stand by that conclusion for the rest of my life, no matter what anyone says.

I’m just unsure if we have the evidence to say if it’s true or not.

There are other researchers who are trying to drill down more into understanding what turns bad behavior on and off. And I’m sure you’re not a fan of him, but Alexander Haslam — [a psychologist who has tried to replicate the prison experiment study, and an academic critic of Zimbardo’s conclusions]

Oh, God! ... no, no, no.

You don’t want to talk about him.

Yeah, okay, No, I don’t want to talk about [him] at all.

Well, the gist of what he and his colleagues are arguing is this: Social identity is a really powerful motivator. And it’s perhaps more influential than situational factors. And perhaps the guards in your experiment became cruel because your warden used his authority to foster a social identity within them. [Here’s a new paper with their latest arguments. ]

I reject that. No, no. That’s their shtick, that’s what they’re pushing.

You don’t assume good faith on their part?

I’m not saying good faith. That’s what their claim to fame is the importance of social identity.

Of course people have social identity. But, there’s also something called situational identity. In a particular situation, you begin to play a role. You are the boss, you are the foreman, you are the drill sergeant, you are the fraternity hazing master. And in that role, which is not the usual you, you begin to do something which is role-bound. ... This is what anybody in this role does. And your behavior then changes.

Is there experimental evidence outside the prison experiment that supports that view?

The view that situation can make a difference?

Yeah. There are plenty of examples in history and current events, but is that something we know as a fact, as an experimental fact?

I don’t know off the top of my head. ...

I’ve always said it’s an interaction. I’m an interactionist. What I’ve said, if you read any of my textbooks, it’s always an interaction between what people bring into a situation, which means genetics and personality, and what the situation brings out in you, which is a social/psychological power of some situations over others. And I will stand by that, my whole career depends on that.

It’s not like I’m mindlessly promoting the situation is dominating everybody.

What would you fear might happen if people stop believing in the integrity of the Stanford Prison Experiment?

The fear is they will lose an important conclusion about the nature of human behavior as being, to some extent, situationally influenced.

You’re afraid they’ll lose an important conclusion even though the study is just a demonstration?

You demonstrate gravity by throwing a ball up and seeing if it comes down. I think you’re insisting on a traditional view of what is scientific, what is a scientific experiment, what is a scientifically validated conclusion. And I am saying from the beginning the Stanford Prison Experiment is a unique and powerful demonstration of how social/situational variables can influence the behavior of some people, some of the time. That’s a very modest conclusion.

All of this controversy is happening now because you gave your notes and tapes from the prison experiment to the Stanford archives. That transparency is commendable. Do you regret it?

No, I don’t regret it. The reason I did it is to make it available for researchers, for anybody, and people have gone through it.

So again, the last thing in the world I need is for people to doubt my honesty, my professional credibility. That’s an attack on me personally, and that I reject and I’m arguing it’s absolutely wrong.

Is it okay if we just move on from the Stanford Prison Experiment? Like you said, it’s a demonstration. Maybe we need to ground our understanding of acts of evil in something a little bit more scientific, to be honest.

At this point, I don’t want anyone to reject that basic conclusion that I’ve said several times in this interview. I don’t want that to be rejected. I would love for there to be better, more scientific evaluation of this conclusion, rather than a bunch of bloggers saying, “We’re gonna shoot it down.”

- Criminal Justice

Most Popular

- 8 million turkeys will be thrown in the trash this Thanksgiving

- Trump’s win is part of a mysterious — and ominous — worldwide trend Member Exclusive

- Take a mental break with the newest Vox crossword

- Trump’s tariff plan is an inflation plan Member Exclusive

- Why Wicked’s politics feel so bizarrely timely

Today, Explained

Understand the world with a daily explainer plus the most compelling stories of the day.

This is the title for the native ad

More in Science

Neuroscience is revealing a fascinating link between gratitude and generosity.

Whatever you do, don’t call the Black in Neuro founder “resilient.”

Science should be bipartisan. Why is our confidence split down party lines?

Who owns the escaped monkeys now? It’s more complicated than you might think.

DMT, “the nuclear bomb of the psychedelic family,” explained.

How Musk’s SpaceX became too big to fail for US national security.

Advertisement

How the Stanford Prison Experiment Worked

- Share Content on Facebook

- Share Content on LinkedIn

- Share Content on Flipboard

- Share Content on Reddit

- Share Content via Email

An Infamous Experiment

The Stanford Prison Experiment is so well-known that even people who've never taken a course in psychology have heard of it, and anyone who does study psychology learns about it in introductory courses. The events of the experiment are told and retold among social scientists and people interested in human behavior like a spooky campfire story.

Philip Zimbardo carried out the experiment, which was funded by the U.S. Office of Naval Research, in August 1971 at Stanford University. The applicants took psychological tests to ensure they were "average," or didn't have psychological disorders or medical conditions. The researchers recruited two dozen male college students using advertisements in newspapers, paying them $15 per day to spend two weeks in a mock prison. They were randomly divided into groups identified as either guards or prisoners, and the prisoners were "arrested" at their homes without warning by real cops and booked at the Palo Alto police station before being taken to the mock prison. The guards weren't instructed how to do their jobs, but they did create a list of restrictive rules the prisoners had to follow, including remaining silent during rest periods and not using each other's names. Zimbardo (acting as prison superintendent) and a team of researchers (one of whom acted as warden) observed the experiment.

The results were horrifying. The guards adopted a rapidly escalating pattern of humiliation and dehumanization against the prisoners. They turned the prisoners against each other and imposed increasingly bizarre punishments, held in check only by the researchers' rule that no physical violence was allowed. Five prisoners were released early because they suffered serious emotional breakdowns or physical problems [source: Zimbardo ]. The other prisoners meekly submitted to whatever treatment the guards dished out and eagerly turned against one another at the prospect of a reward, such as being allowed to sleep in a cell with beds and blankets instead of on the concrete floor. The participants became so invested in their roles that the entire experiment was halted after just six days, when Zimbardo realized it was spiraling out of control.

The lesson of the Stanford Prison Experiment seems pretty obvious: There's a cruel streak inside all people, a latent evil waiting to be unleashed should they be given the slightest hint of authority and power. By the same token, the results of the experiment could show that people are driven to obey, conform and respond to authority with submission and compliance. It's a profound and disquieting statement about human nature that 24 "average" young men could be so easily and quickly twisted.

But things aren't really so simple. The lessons to be learned aren't confined to "guards" and "prisoners," but extend to prisons and other powerful institutions, and even to the ways scientists conduct experiments on human behavior. What really happened at the "Stanford County Prison"? Let's find out.

In interviews, Zimbardo often describes the process of dividing the participants into guards and prisoners as a coin flip. This deserves some clarification. Randomization , a method of sampling in experiments, is determined using a computer program of some kind (even in 1971), because often complex factors need to be accounted for to control variables. An actual coin flip couldn't be used even in the Stanford Prison Experiment, because you might not get 24 heads and 24 tails in 48 flips. The odds of an individual participant getting placed in one group or the other were indeed 50-50, like a coin flip, but the researchers didn't actually flip a coin.

Please copy/paste the following text to properly cite this HowStuffWorks.com article:

The Stanford Prison Experiment: The Power of the Situation

- First Online: 20 January 2024

Cite this chapter

- Harry Perlstadt ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0233-0463 3

Part of the book series: Clinical Sociology: Research and Practice ((CSRP))

560 Accesses

Philip Zimbardo is best known for his 1971 Stanford Prison Experiment (SPE). Early in his career, he conducted experiments in the psychology of deindividualization, in which a person in a group or crowd no longer acts as a responsible individual but is swept along and participates in antisocial actions. After moving to Stanford University, he began to focus on institutional power over the individual in group settings, such as long-term care facilities for the elderly and prisons. His research proposal for a simulated prison was approved by the Stanford University Human Subjects Research Review Committee in July 1971. He built a mock prison in the basement of the University’s psychology building and recruited college-aged male subjects to play prisoners and guards. The study began on Sunday, August 8th, and was to run for 2 weeks but ended on Friday morning August 13th. In less than a week, several of the mock guards hazed and brutalized the mock prisoners, some of whom found ways of coping, while others exhibited symptoms of mental breakdown.

The degree of civilization in a society can be judged by entering its prisons. — attributed to Fyodor Dostoevsky, The House of the Dead

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Alexander, M. (2001, August 22). Thirty years later, Stanford Prison Experiment lives on. Stanford Report . Accessed April 22, 2022, from https://news.stanford.edu/news/2001/august22/prison2-822.html?msclkid=7d17df2ec26f11ec8086da6bf715d359

Amdur, R. J. (2006). Provisions for data monitoring. In E. A. Bankert, & J. R. Amdur (Eds.), Institutional review board: Management and function , 2nd edition (pp. 160–165). Jones & Bartlet

Google Scholar

Banuazizi, A., & Movahedi, S. (1975). Interpersonal dynamics in a simulated prison: A methodological analysis. American Psychologist, 30 , 152–160.

Article Google Scholar

Blau, P. M. (1964). Exchange and power in social life . Wiley.

Farkas, M. A. (2000). A typology of correctional officers. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 44 (4), 431–449. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306624X00444003

Festinger, L., Pepitone, A., & Newcombe, T. (1952). Some consequences of deindividuation in a group. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 47 , 382–389.

French, J. R. P., & Raven, B. (1959). The bases of social power. In D. Cartwright (Ed.), Studies in social power (pp. 150–167). Institute for Social Research.

Frohnmayer, D. (2004, November 30). “Situational ethics, social deception, and lessons of machiavelli” Judge learned hand award Luncheon Oregon chapter of the American Jewish Committee Tuesday . http://president.uoregon.edu/speeches/situationalethics.shtml

Goffman, E. (1961). Asylums. Essays on the social situation of mental patients and other inmates . Doubleday Anchor. http://www.diligio.com/goffman.htm

Gross, B. (2008, Winter/December). Prison violence: Does brutality come with the badge? The Forensic Examiner . http://www.theforensicexaminer.com/archive/winter08/6/

Haney, C., Banks, C., & Zimbardo, P. G. (1973). A study of prisoners and guards in a simulated prison. Naval Research Review, 30 , 4–17.

Lovibond, S. H., Mithiran, & Adams, W. G. (1979). Effects of three experimental prison environments on the behaviour of non-convict volunteer subjects. Australian Psychologist, 14 (3), 273–285.

Maslach, C. (1971). The “truth” about false confessions. The Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 20 (2), 141–146. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0031675

Maslach, C. (1974). Social and personal bases of individuation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 29 (3), 411–425. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0036031

Maslach, C., Marshall, G., & Zimbardo, P. G. (1972). Hypnotic control of peripheral skin temperature: A case report. Psychophysiology, 9 (6), 600–605. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8986.1972.tb00769.x

Morgan, A. H., Lovibond, S. H., & Adams, W. G. (1979). Comments on S. H. Lovibond, Mithiran, & W. G. Adams: “The effects of three experimental prison environments on the behaviour of non-convict volunteer subjects”. Australian Psychologist, 14 (3), 273–287.

NHLBI. (2008). National Heart Lung and Blood Institute. Data and safety monitoring policy . http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/funding/policies/dsmpolicy.htm

O’Toole, K. (1997, January 8). The Stanford prison experiment: Still powerful after all these years. Stanford report . Stanford University News Service. http://www.stanford.edu/news/gif/snewshd.gif

Prescott, C. (2005, April 28). The lie of the Stanford prison experiment. The Stanford Daily .

Sawyer, K. D. (2021). George Jackson, 50 years later . Accessed January 18, 2022, from https://sfbayview.com/2021/08/george-jackson-50-years-later/?msclkid=4afbd2c7c26b11eca875b013aedf20b3

Schaufeli, W. B., & Peeters, M. C. W. (2000). Job stress and burnout among correctional officers: A literature review. International Journal of Stress Management, 7 (1), 19–48. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1009514731657

Schlesinger Report. (2004). Final report of the independent panel to review Department of Defense Detention Operations . http://news.bbc.co.uk/nol/shared/bsp/hi/pdfs/24_08_04_abughraibreport.pdf

SPE Website. (n.d.). Stanford Prison Experiment Website. The story: An overview of the experiment . Accessed February 28, 2022, from https:// www.prisonexp.org/the-story

Weber, M. (1947). The theory of social and economic organization . Oxford University Press.

Zimbardo, P. (1969). The human choice: Individuation, reason and order versus deindividuation, impulse, and chaos. In W. J. Arnold & D. Levine (Eds.), Nebraska Symposium on Motivation (Vol. 17, pp. 237–307). University of Nebraska Press.

Zimbardo, P. G. (1970). The human choice: Individuation, reason, and order versus deindividuation, impulse, and chaos. In W. J. Arnold & D. Levine (Eds.), 1969 Nebraska symposium on motivation (pp. 237–307). University of Nebraska Press. Accessed January 19, 2022, from https://stacks.stanford.edu/file/gk002bt7757/gk002bt7757.pdf

Zimbardo, P. G. (1971a). Application for institutional approval of research involving human subjects . August, 1971. Available at: http://www.prisonexp.org/pdf/humansubjects.pdf . Accessed December 1, 2023.

Zimbardo, P. G. (1971b). Prison life study: General information sheet . August, 1971. Available at: http://www.prisonexp.org/pdf/geninfo.pdf . Accessed December 1, 2023.

Zimbardo, P. G. (2008). The lucifer effect: Understanding how good people turn evil . Random House.

Zimbardo, P. G., Haney, C., Banks, W. C., & Jaffe, D. (1972). Stanford prison experiment . Philip G. Zimbardo, Inc. (Tape recording).

Zimbardo, P. G., Haney, C., Banks, W. C., & Jaffe, D. (1972, April 8). The mind is a formidable jailer: A Pirandellian prison. New York Times Magazine, Section 6, 36, ff.

Zimbardo, P. G., Marshall, G., & Maslach, C. (1971). Liberating behavior from time-bound control: Expanding the present through hypnosis. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 1 (4), 305–323. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.1971.tb00369.x

Zimbardo, P. G., Marshall, C., White, G., & Maslach, C. (1973). Objective assessment of hypnotically induced time distortion. Science, 181 (4096), 282–284.

Zimbardo, P. G., Maslach, C., & Haney, C. (2000). Chapter 11: Reflections on the Stanford prison experiment: Genesis, transformations, consequences. In T. Blass (Ed.), Obedience to authority: Current perspectives on the milgram paradigm (pp. 193–237). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Download references

Acknowledgments

I wish to thank Chris Herrera, Jonathan K. Rosen, David Segal and Ruth Spivak for their comments on this chapter.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

(emeritus) Department of Sociology, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI, USA

Harry Perlstadt

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Perlstadt, H. (2023). The Stanford Prison Experiment: The Power of the Situation. In: Assessing Social Science Research Ethics and Integrity. Clinical Sociology: Research and Practice. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-34538-8_8

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-34538-8_8

Published : 20 January 2024

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-031-34537-1

Online ISBN : 978-3-031-34538-8

eBook Packages : Social Sciences Social Sciences (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

The Stanford Prison Experiment

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Cara Lustik is a fact-checker and copywriter.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Cara-Lustik-1000-77abe13cf6c14a34a58c2a0ffb7297da.jpg)

- Participants

- Setting and Procedure

In August of 1971, psychologist Philip Zimbardo and his colleagues created an experiment to determine the impacts of being a prisoner or prison guard. The Stanford Prison Experiment, also known as the Zimbardo Prison Experiment, went on to become one of the best-known studies in psychology's history —and one of the most controversial.

This study has long been a staple in textbooks, articles, psychology classes, and even movies. Learn what it entailed, what was learned, and the criticisms that have called the experiment's scientific merits and value into question.

Purpose of the Stanford Prison Experiment

Zimbardo was a former classmate of the psychologist Stanley Milgram . Milgram is best known for his famous obedience experiment , and Zimbardo was interested in expanding upon Milgram's research. He wanted to further investigate the impact of situational variables on human behavior.

Specifically, the researchers wanted to know how participants would react when placed in a simulated prison environment. They wondered if physically and psychologically healthy people who knew they were participating in an experiment would change their behavior in a prison-like setting.

Participants in the Stanford Prison Experiment

To carry out the experiment, researchers set up a mock prison in the basement of Stanford University's psychology building. They then selected 24 undergraduate students to play the roles of both prisoners and guards.

Participants were chosen from a larger group of 70 volunteers based on having no criminal background, no psychological issues , and no significant medical conditions. Each volunteer agreed to participate in the Stanford Prison Experiment for one to two weeks in exchange for $15 a day.

Setting and Procedures

The simulated prison included three six-by-nine-foot prison cells. Each cell held three prisoners and included three cots. Other rooms across from the cells were utilized for the jail guards and warden. One tiny space was designated as the solitary confinement room, and yet another small room served as the prison yard.

The 24 volunteers were randomly assigned to either the prisoner or guard group. Prisoners were to remain in the mock prison 24 hours a day during the study. Guards were assigned to work in three-man teams for eight-hour shifts. After each shift, they were allowed to return to their homes until their next shift.

Researchers were able to observe the behavior of the prisoners and guards using hidden cameras and microphones.

Results of the Stanford Prison Experiment

So what happened in the Zimbardo experiment? While originally slated to last 14 days, it had to be stopped after just six due to what was happening to the student participants. The guards became abusive and the prisoners began to show signs of extreme stress and anxiety .

It was noted that:

- While the prisoners and guards were allowed to interact in any way they wanted, the interactions were hostile or even dehumanizing.

- The guards began to become aggressive and abusive toward the prisoners while the prisoners became passive and depressed.

- Five of the prisoners began to experience severe negative emotions , including crying and acute anxiety, and had to be released from the study early.

Even the researchers themselves began to lose sight of the reality of the situation. Zimbardo, who acted as the prison warden, overlooked the abusive behavior of the jail guards until graduate student Christina Maslach voiced objections to the conditions in the simulated prison and the morality of continuing the experiment.

One possible explanation for the results of this experiment is the idea of deindividuation , which states that being part of a large group can make us more likely to perform behaviors we would otherwise not do on our own.

Impact of the Zimbardo Prison Experiment

The experiment became famous and was widely cited in textbooks and other publications. According to Zimbardo and his colleagues, the Stanford Prison Experiment demonstrated the powerful role that the situation can play in human behavior.

Because the guards were placed in a position of power, they began to behave in ways they would not usually act in their everyday lives or other situations. The prisoners, placed in a situation where they had no real control , became submissive and depressed.

In 2011, the Stanford Alumni Magazine featured a retrospective of the Stanford Prison Experiment in honor of the experiment’s 40th anniversary. The article contained interviews with several people involved, including Zimbardo and other researchers as well as some of the participants.

In the interviews, Richard Yacco, one of the prisoners in the experiment, suggested that the experiment demonstrated the power that societal roles and expectations can play in a person's behavior.

In 2015, the experiment became the topic of a feature film titled The Stanford Prison Experiment that dramatized the events of the 1971 study.

Criticisms of the Stanford Prison Experiment

In the years since the experiment was conducted, there have been a number of critiques of the study. Some of these include:

Ethical Issues

The Stanford Prison Experiment is frequently cited as an example of unethical research. It could not be replicated by researchers today because it fails to meet the standards established by numerous ethical codes, including the Code of Ethics of the American Psychological Association .

Why was Zimbardo's experiment unethical?

Zimbardo's experiment was unethical due to a lack of fully informed consent, abuse of participants, and lack of appropriate debriefings. More recent findings suggest there were other significant ethical issues that compromise the experiment's scientific standing, including the fact that experimenters may have encouraged abusive behaviors.

Lack of Generalizability

Other critics suggest that the study lacks generalizability due to a variety of factors. The unrepresentative sample of participants (mostly white and middle-class males) makes it difficult to apply the results to a wider population.

Lack of Realism

The Zimbardo Prison Experiment is also criticized for its lack of ecological validity. Ecological validity refers to the degree of realism with which a simulated experimental setup matches the real-world situation it seeks to emulate.

While the researchers did their best to recreate a prison setting, it is simply not possible to perfectly mimic all the environmental and situational variables of prison life. Because there may have been factors related to the setting and situation that influenced how the participants behaved, it may not truly represent what might happen outside of the lab.

Recent Criticisms

More recent examination of the experiment's archives and interviews with participants have revealed major issues with the research method , design, and procedures used. Together, these call the study's validity, value, and even authenticity into question.

These reports, including examinations of the study's records and new interviews with participants, have also cast doubt on some of its key findings and assumptions.

Among the issues described:

- One participant suggested that he faked a breakdown so he could leave the experiment because he was worried about failing his classes.

- Other participants also reported altering their behavior in a way designed to "help" the experiment .

- Evidence suggests that the experimenters encouraged the guards' behavior and played a role in fostering the abusive actions of the guards.

In 2019, the journal American Psychologist published an article debunking the famed experiment. It detailed the study's lack of scientific merit and concluded that the Stanford Prison Experiment was "an incredibly flawed study that should have died an early death."

In a statement posted on the experiment's official website, Zimbardo maintains that these criticisms do not undermine the main conclusion of the study—that situational forces can alter individual actions both in positive and negative ways.

The Stanford Prison Experiment is well known both inside and outside the field of psychology . While the study has long been criticized for many reasons, more recent criticisms of the study's procedures shine a brighter light on the experiment's scientific shortcomings.

Stanford University. About the Stanford Prison Experiment .

Stanford Prison Experiment. 2. Setting up .

Sommers T. An interview with Philip Zimbardo . The Believer.

Ratnesar R. The menace within . Stanford Magazine.

Jabbar A, Muazzam A, Sadaqat S. An unveiling the ethical quandaries: A critical analysis of the Stanford Prison Experiment as a mirror of Pakistani society . J Bus Manage Res . 2024;3(1):629-638.

Horn S. Landmark Stanford Prison Experiment criticized as a sham . Prison Legal News .

Bartels JM. The Stanford Prison Experiment in introductory psychology textbooks: A content analysis . Psychol Learn Teach . 2015;14(1):36-50. doi:10.1177/1475725714568007

American Psychological Association. Ecological validity .

Blum B. The lifespan of a lie . Medium .